After La Vida Nueva After La Vida Nueva

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Views of Main Street, the First Major New York Solo Museum Exhibition by Rodney Mcmillian, Leads the Spring 2016 Exhibitions Roster at the Studio Museum in Harlem

MEDIA RELEASE The Studio Museum in Harlem 144 West 125th Street New York, NY 10027 studiomuseum.org/press Contact: Elizabeth Gwinn Kate Lydecker The Studio Museum in Harlem Polskin Arts and Communications Counselors [email protected] [email protected] 646.214.2142 212.715.1602 VIEWS OF MAIN STREET, THE FIRST MAJOR NEW YORK SOLO MUSEUM EXHIBITION BY RODNEY MCMILLIAN, LEADS THE SPRING 2016 EXHIBITIONS ROSTER AT THE STUDIO MUSEUM IN HARLEM New Projects by Ebony G. Patterson and Rashaad Newsome, Thematic Installations from the Permanent Collection and the Latest Presentations in the Harlem Postcards Series Round Out the Spring Season New York, NY, December 16, 2015—A major solo exhibition by the Los Angeles-based artist Rodney McMillian—his first in a New York City museum—will fill the main gallery of The Studio Museum in Harlem when the spring exhibition season begins on March 24, 2016. Joining Rodney McMillian: Views of Main Street, and remaining on view with it through June 26, will be new projects by Ebony G. Patterson and Rashaad Newsome, a pair of thematic installations from the unparalleled permanent collection and the latest presentation in the exhibition series Harlem Postcards. Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator of the Studio Museum, said, “This spring’s exhibitions offer insights from three vital artists with burgeoning reputations who are doing exceptionally inventive and multifaceted work at mid-career. We are proud to welcome them to their first solo exhibitions at The Studio Museum in Harlem. We are also delighted to frame these new and recent works with presentations that bring out critical Rodney McMillian, Untitled, 2009. -

Catalina Parra

LUDLOW 38 Curatorial Residencies 38 Ludlow Street · New York 10002 · ☎ +1 212 228 6848 · [email protected] CATALINA PARRA May 22 – June 26, 2011 Reception for the artist: Sunday May 22, 1-6pm MINI/Goethe-Institut Curatorial Residencies Ludlow 38 is pleased to announce a solo show by Catalina Parra. For this exhibition Parra has selected works made between 1969 and today, stemming from extended periods in Germany, Chile, Canada and the United States. The exhibition opens with a series of crayon drawings executed by Parra at the beginning of her career near Lake Constance, Germany. Also presented are early collages and photographs including material that led to Parra’s contribution for Manuscritos (1975), the fi rst publication of art criticism after the Chilenean military coup of 1973. Relying on a variety of media including drawing, collage and fi lm, Parra has demonstrated an extraordinary sensibility towards the socio-political affairs that take place around us. As artist Coco Fusco outlined in a 1991 essay that was published in the catalogue for Parra’s solo show at the Intar Gallery, Parra “concentrates on the process of coming to terms with information that connotes something different than what it denotes.” With an aesthetic awareness that draws parallels to the work of Hannah Höch and John Heartfi eld, the artist repeatedly begins her constructions from newspaper advertisements to create hand-sewn collages and mixed media works. Her newspaper collages are executed in series form, each series containing multiple variations. The exhibition at Ludlow 38 features pieces from a number of these series including Coming your way (Banff, 1994), The Human touch (1989) and Here, there, everywhere (1992). -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

RASHAAD NEWSOME B. 1979 New Orleans, LA Resides New York, NY

RASHAAD NEWSOME b. 1979 New Orleans, LA Resides New York, NY Education 2004 Film/Video Arts Inc. 2001 Tulane University, B.A. Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 ICON, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA Order of Chivalry, Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, GA Silence Please The Show Is About To Begin, Art Gallery of York University, Toronto, CA 2014 LS.S, Marlborough Gallery, New York, NY FIVE, The Drawing Center, New York, NY 2013 Score, Gallerie Henrik Springmann, Berlin, DE The Armory Show, Marlborough Chelsea, New York, NY Rashaad Newsome: King of Arms, The New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, LA 2012 Converge, McColl Center for Visual Art, Charlotte, NC 2011 Shade Compositions, Galerie Stadtpark, Krems, AT Rashaad Newsome: Herald, Marlborough Chelsea, New York, NY Rashaad Newsome/MATRIX 161, The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT 2010 Rashaad Newsome: Videos and Performance 2005-2010, Syracuse University Art Galleries, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Honorable Ordinaries, Ramis Barquet Gallery, New York, NY Futuro, ar/ge Kunst Galerie Museum, Bolzano, IT 2009 Rashaad Newsome: Standards, Ramis Barquet Gallery, New York, NY 2008 Untitled (Banji Cunt), Talman + Monroe, Brooklyn, NY Compositions, Location1, New York, NY Selected Group Exhibitions 2015 Performance and Remnant, The Fine Arts Society, London, UK Fabulous, Shirin Gallery, New York, NY A Curious Blindness, Columbia University, New York, NY 2014 Killer Heels, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY Summer Group Exhibition, Marlborough Gallery, New York, NY BLACK -

Intersecciones Entre Feminismo

DOI: 10.26807/cav.v0i08.262 INTERSECCIONES ENTRE FEMINISMO, ARTE Y POLÍTICA: UNA MIRADA A LA “ESCENA DE AVANZADA” PARA DESNEUTRALIZAR LOS SIGNOS DE LA CULTURA Intersections between feminism, art and politics: A look at the “Advanced Scene” to deneutralize the signs of culture Gina Gabriela López ISSN (imp): 1390-4825 ISSN (e): 2477-9199 Fecha de recepción: 09/29/19 Fecha de aceptación: 11/16/19 118 INDEX #08 Resumen: El artículo presenta la producción artística de mujeres en Chile que desafiaron la dictadura militar y patriarcal, entre 1973 y 1990, como parte de la denominada “Escena de avanzada”. A partir de los aportes de la teórica franco chilena Nelly Richard, este texto expone la relación entre la autoría biográfica y la representación de género, es decir, entre el hecho de ser una artista mujer y los registros culturales simbólicos de lo femenino. Así, problematiza la interpretación tradicional del arte producido por mujeres y sitúa lo femenino como disidencia, como una subjetividad alternativa y contradominante capaz de desarticular los mecanismos de significación de la cultura hegemónica. Palabras clave: mujeres, arte, política, feminismo, Chile, dictadura, género Abstract: This article introduces the artistic production of women in Chile who challenged the military and patriarchal dictator- ship, between 1973 and 1990, as part of the movement called "Advanced Scene". Based on the contributions of the franco chilean theorist Nelly Richard, this text sets out the relationship between biographical authorship and the gender representation, in other words with the fact of being a woman artist and the symbolic cultural records of the feminine. -

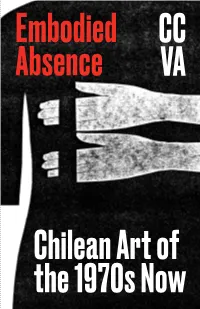

Embodied Absence Chilean Ar

Embodied Absence Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Carpenter Center Embodied Absence for the Visual Arts Chilean Art of the 1970s Now Oct 27, 2016–Jan 8, 2017 Works by Elías Adasme, Carmen This exhibition is co-organized Beuchat with Felipe Mujica and with DRCLAS as part of its research Johanna Unzueta, CADA (Colectivo project Conceptual Stumblings. Acciones de Arte), Francisco Copello, Exhibition and program support Luz Donoso, Juan Downey, Carlos is also provided by Harvard Leppe, Catalina Parra, Lotty University Committee on the Rosenfeld, UNAC (Unión por la Arts. The first iteration, Embodied Cultura), Cecilia Vicuña, and Raúl Absence: Ephemerality and Zurita with Cristóbal Lehyt Collectivity in Chilean Art of the 1970s (September 2015–January Guest curated by Liz Munsell, 2016), was organized by Museo Assistant Curator of Contemporary de la Solidaridad Salvador Art & Special Initiatives, Museum of Fine Allende, Santiago, Chile, with its Arts, Boston, and visiting curator, David substantial support in research Rockefeller Center for Latin American and production of works, in Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University collaboration with DRCLAS. Embodied Absence Liz Munsell Following the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 1973,1 Chilean artists residing in Santiago and abroad created artworks that spoke to their experience of political, social, and geographic marginalization. Inside the country, they adopted the highly coded languages of conceptual art to evade censorship, exhibited work in public space in lieu of institutional support, and formed independently run galleries and artist collectives to protect their individual identities. Artists abroad staged public events and made artwork in solidarity with those at home. Their exhibitions, performances, interventions, and workshops spread awareness among international audiences and broke down isolating conditions within Chile. -

Rashaad Newsome B. 1979- Born in New Orleans, LA Lives and Works in Brooklyn, NY

Rashaad Newsome b. 1979- Born in New Orleans, LA Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY Education 2004 Digital Post Production, Film/Video Arts Inc., NY 2001 BFA, Tulane University, LA Selected Solo Exhibition 2020 Black Magic, Leslie-Lohman Museum, New York, NY To Be Real, Fort Mason Center for Art & Culture, San Francisco, CA 2019 To Be Real, Philadelphia Photo Arts Center, Philadelphia, PA ICON/STOP PLAYING IN MY FACE!, Museum of the African Diaspora, San Francisco, CA 2017 KNOT, McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX Reclaiming Our Time, Debuck Gallery, New York, NY ICON, Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI Mélange, Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, LA 2016 STOP PLAYING IN MY FACE!, DeBuck Gallery, New York, NY THIS IS WHAT I WANT TO SEE, Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, NY 2015 ICON, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA Order of Chivalry, Savannah College of Art and Design, GA Silence Please The Show Is About To Begin, Art Gallery of York University, Toronto, Canada 2014 LS.S, Marlborough Gallery, New York, NY FIVE, The Drawing Center, New York, NY 2013 Score, Gallerie Henrik Springmann, Berlin, Germany The Armory Show, Marlborough Chelsea, New York, NY King of Arms, The New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, LA 2011 Shade Compositions, Galerie Stadtpark, Krems, Austria Herald, Marlborough Chelsea, New York, NY Rashaad Newsome/MATRIX 161, The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT 2010 Honorable Ordinaries, Ramis Barquet Gallery, New York, NY Futuro, ar/ge Kunst Galerie Museum, Bolzano, Italy 2009 Standards, Ramis Barquet Gallery, New York, NY 2008 Compositions, Location1, New York, NY Selected Group Exhibition 2021 Today and Tomorrow, Gana Art Center, Seoul, South Korea The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA 2020 Mothership: Voyage into Afrofuturism, Oakland Museum of California, Oakland, CA Sounds Hannam #13, 35 Daesagwan-ro, Yongsan-gu, Seoul 04401, Korea t. -

Nelly Richard's Crítica Cultural: Theoretical Debates and Politico- Aesthetic Explorations in Chile (1970-2015)

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Nelly Richard’s crítica cultural : theoretical debates and politico-aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970- 2015) https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40178/ Version: Full Version Citation: Peters Núñez, Tomás (2016) Nelly Richard’s crítica cultural : theoretical debates and politico-aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970- 2015). [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Birkbeck, University of London Nelly Richard's crítica cultural: Theoretical debates and politico- aesthetic explorations in Chile (1970-2015) Tomás Peters Núñez Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2016 This thesis was funded by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Ministerio de Educación, Chile. 2 Declaration I, Tomás Peters Núñez, declare that this thesis is all my own work. Date 25/January/2016 3 ABSTRACT This thesis describes and analyses the intellectual trajectory of the Franco- Chilean cultural critic Nelly Richard between 1970 and 2015. Using a transdisciplinary approach, this investigation not only analyses Richard's series of theoretical, political, and essayistic experimentations, it also explores Chile’s artistic production (particularly in the visual arts) and political- cultural processes over the past 45 years. In this sense, it is an examination, on the one hand, of how her critical work and thought emerged in a social context characterized by historical breaks and transformations and, on the other, of how these biographical experiences and critical-theoretical experiments derived from a specific intellectual practice that has marked her professional profile: crítica cultural. -

Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America Mari Carmen Ramı´Rez

blueprint circuits: conceptual art and politics in latin america mari carmen ramı´rez Circuit: . a course around a periphery . space enclosed within a circumference . a system for two-way communication.1 In 1972, taking stock of the status of Conceptual art in Western countries, the Spanish art historian Simo´n Marcha´n Fiz observed the beginnings of a tendency toward “ideological con- ceptualism” emerging in peripheral societies such as Argentina and Spain.2 This version of Conceptual art came on the heels of the controversial propositions about the nature of art and artistic practice introduced in the mid-1960s by the North Americans Robert Barry, Mel Bochner, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, and Lawrence Weiner, as well as the British group Art & Language. These artists investigated the nature of the art object as well as the institutional mechanisms that support it, and their results tended to de-emphasize or elimi- nate the art object in favor of the process or ideas underlying it. North American Conceptual artists also questioned the role of museums and galleries in the promotion of art, its market status, and its relationship with the audience. This exposure of the functions of art in both social and cultural circuits has significantly redefined contemporary artistic practice over the last thirty years. For Marcha´n Fiz, the distinguishing feature of the Spanish and Argentine forms of Con- mari carmen ramı ceptualism was extending the North American critique of the institutions and practices of art to an analysis of political and social issues. At the same time when he made these observations, the radical edge of North American Conceptual art’s critique was obscured by the generalizing, ´ rez reductive posture of Kosuth’s “art-as-idea-as-idea.”3 In Kosuth’s model the artwork as concep- tual proposition is reduced to a tautological or self-reflexive statement. -

Museum Activism

MUSEUM ACTIVISM Only a decade ago, the notion that museums, galleries and heritage organisations might engage in activist practice, with explicit intent to act upon inequalities, injustices and environmental crises, was met with scepticism and often derision. Seeking to purposefully bring about social change was viewed by many within and beyond the museum community as inappropriately political and antithetical to fundamental professional values. Today, although the idea remains controversial, the way we think about the roles and responsibilities of museums as knowledge- based, social institutions is changing. Museum Activism examines the increasing significance of this activist trend in thinking and practice. At this crucial time in the evolution of museum thinking and practice, this ground-breaking volume brings together more than fifty contributors working across six continents to explore, analyse and critically reflect upon the museum’s relationship to activism. Including contribu- tions from practitioners, artists, activists and researchers, this wide-ranging examination of new and divergent expressions of the inherent power of museums as forces for good, and as activists in civil society, aims to encourage further experimentation and enrich the debate in this nascent and uncertain field of museum practice. Museum Activism elucidates the largely untapped potential for museums as key intellectual and civic resources to address inequalities, injustice and environmental challenges. This makes the book essential reading for scholars and students of museum and heritage studies, gallery studies, arts and heritage management, and politics. It will be a source of inspiration to museum practitioners and museum leaders around the globe. Robert R. Janes is a Visiting Fellow at the School of Museum Studies , University of Leicester, UK, Editor-in-Chief Emeritus of Museum Management and Curatorship, and the founder of the Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice. -

Catalina Parra Catalina Parra

1 Catalina Parra Catalina Parra Biografía Catalina Parra, artista visual. Nació en Santiago, Chile, en 1940. De formación autodidacta, hija del poeta Nicanor Parra. Vivió en Alemania entre 1968 y 1972; en 1980 viajó a New York con la Beca Guggenheim permaneciendo allí hasta el año 2000. Entonces se trasladó a Buenos Aires para ejercer el cargo de Agregada Cultural de Chile en Argentina, país donde residió hasta el 2009. Ha sido Artista en Residencia en: Museo del Barrio, New York, Estados Unidos, 1990; SUNY Purcharse, State University of New York, Estados Unidos, 1991; Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Estados Unidos, 1993; Banff Center for the Arts, Canadá, 1993-1994; Civitella Ranieri, Umbertide, Italia, 1995. Premios y distinciones 1977 Premio de Honor en Grabado y Dibujo, Tercera Bienal Internacional de Arte de Valparaíso, Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes, Valparaíso, Chile. 1980 Beca Fundación Guggenhein, New York, Estados Unidos. 1992 Premio de la Crítica en Artes Visuales, ex aequo con Francisco Smythe, Círculo de Críticos de Arte, Santiago, Chile. Exposiciones EXPOSICIONES INDIVIDUALES 1971 Galerie Press, Konstanz, Alemania. 1977 Imbunches Catalina Parra, Galeria Época, Santiago, Chile. 1981 Museum of Modern Art, MOMA, New York, Estados Unidos. 2 1983 Ivonne Seguy Gallery, New York, Estados Unidos. 1987 Terne Gallery, New York, Estados Unidos. 1989 Catalina Parra, Galería Plástica Nueva, Santiago, Chile. 1990 Gallerie Zographia, Bordeaux, Francia. 1991 Musee des Arts, Sainte Foy, Francia. 1991 INTAR Gallery, Nueva York, Estados Unidos. 1991 Médiatheque Municipale, Libourne, Francia. 1992 Lehman College Art Gallery, New York, Estados Unidos. 1992 Catalina Parra: Retrospectiva, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, MAC, Universidad de Chile. -

Never Say in Private What You (Won't) Say in Public

NEVER SAY IN PRIVATE WHAT YOU (WON’t) SAY IN PUBLIC – Close to the end of post-production, on January 2014, Carlos Amorales suggested me to compile the process of the film “The Man Who Did All Things Forbidden” in the form of a book. – 1 CARLOS AMORALES_OSP_3_CORRECTION.indd 1 08/04/14 16:43 CONTENTS 4 Director’s NOTES FOR PRE-PRODUCTION 16 EXCELSIOR 24 IdEOLOGICAL CUBISM 26 EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN DIRECTOR CARLOS AMORALES AND ACTOR PHILIPPE Editors: EUSTACHON Isaac Muñoz Olvera and Carlos Amorales 50 FIRST ARGUMENT Translation: Gabriela Jauregui and Alan Page 65 DIALOGUES Design: Iván Martínez and Laura Pappa 120 SCRIPT DIAGRAMS dURING THE SHOOT Texts, dialogs and diagrams: Carlos Amorales, Elsa-Louise 132 DIRECTING DIAGRAMS Manceaux, Isaac Muñoz Olvera, dURING THE SHOOT Manuela García, Philippe Eustachon, Millaray Lobos, Jacinta Langlois, Camilo Carmona, Antonia Rossi, Darío Schvarzstein, Claudio Vargas, Peter Rosenthal, Francisca Gazitua, dancers 1 and 2. Thanks to Edgar Hernández for his kind advice and all authors of cited images and texts. Cover: “Remake on Wolf Vostell proposal for Documenta” by Carlos Amorales, 2014 Page 50: Image taken from Juan Luis Martinez “La Poesia Chilena”, Ediciones Archivo 1978 3 CARLOS AMORALES_OSP_3_CORRECTION.indd 2-3 08/04/14 16:43 #1 Director’s NOTES FOR PRE-PRODUCTION – Between July and September 2013, a group of artists gathered at Carlos Amorales’ studio in Mexico City, to freely discuss his concerns for the new film. We used to sit around a square table. He drew diagrams while he spoke.