Post-Human Pop : from Simulation to Assimilation Cookney, DJ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

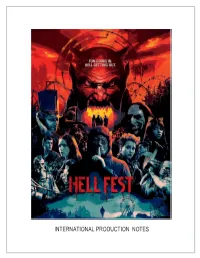

International Production Notes

INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION NOTES PUBLICITY CONTACT Julia Benaroya Lionsgate +1 310-255-3095 [email protected] US RELEASE DATE: SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 RUNNING TIME: 89 MINUTES TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCTION INFORMATION ..................................... 4 ABOUT THE CAST ................................................ 14 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS ..................................... 18 END CREDITS ...................................................... 26 3 PRODUCTION INFORMATION In this terrifying thrill ride, college student Natalie is visiting her childhood best friend Brooke and her roommate Taylor. If it was any other time of year these three and their boyfriends might be heading to a concert or bar, but it is Halloween which means that like everyone else they will be bound for Hell Fest – a sprawling labyrinth of rides, games and mazes that travels the country and happens to be in town. Every year thousands follow Hell Fest to experience fear at the ghoulish carnival of nightmares. But for one visitor, Hell Fest is not the attraction – it is a hunting ground. An opportunity to slay in plain view of a gawking audience, too caught up in the terrifyingly fun atmosphere to recognize the horrific reality playing out before their eyes. As the body count and frenzied excitement of the crowds continue to rise, he turns his masked gaze to Natalie, Brooke, Taylor and their boyfriends who will fight to survive the night. CBS FILMS and TUCKER TOOLEY ENTERTAINMENT present a VALHALLA MOTION PICTURES production HELL FEST Starring Amy Forsyth, Reign Edwards, Bex Taylor-Klaus and Tony Todd. Casting by Deanna Brigidi, CSA and Lisa Mae Fincannon. Music by Bear McCreary. Costume Designer Eulyn C. Hufkie. Editors Gregory Plotkin, ACE and David Egan. -

Solid-State Detector SPECT Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

THE STATE OF THE ART Solid-State Detector SPECT Myocardial Perfusion Imaging Piotr J. Slomka1, Robert J.H. Miller1, Lien-Hsin Hu1,2, Guido Germano1, and Daniel S. Berman1 1Department of Imaging, Medicine, and Biomedical Sciences, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. California; and 2Department of Nuclear Medicine, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan Additionally, the physical space requirements for solid-state cam- There has been an evolutionary leap in SPECT imaging with the era systems have been significantly reduced because photomulti- advent of camera systems that use solid-state crystals and novel plier tubes are no longer required. New solid-state scanners can collimator designs configured specifically for cardiac imaging. also be coupled with diagnostic-quality CT systems suitable for Solid-state SPECT camera systems have facilitated dramatic calcium scanning or coronary CT angiography. With the growing reductions in both imaging time and radiation dose while maintain- clinical experience using solid-state SPECT camera systems, there ing high diagnostic accuracy. These advances are related to is also emerging evidence demonstrating comparable or superior simultaneous improvement in photon sensitivity due to the collima- diagnostic and prognostic utility. tor and imaging geometry, as well as image resolution due to the improved energy resolution of the new crystals. Improved photon This review summarizes current solid-state SPECT technology and sensitivity has facilitated fast or low-dose myocardial perfusion clinical applications, including emerging techniques for myocardial imaging (MPI), and early dynamic imaging has emerged as a blood flow (MBF) quantitation. We will also discuss imaging technique for assessing myocardial blood flow with SPECT. -

American Rock with a European Twist: the Institutionalization of Rock’N’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20Th Century)❧

75 American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century)❧ Maria Kouvarou Universidad de Durham (Reino Unido). doi: dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit57.2015.05 Artículo recibido: 29 de septiembre de 2014 · Aprobado: 03 de febrero de 2015 · Modificado: 03 de marzo de 2015 Resumen: Este artículo evalúa las prácticas desarrolladas en Francia, Italia, Grecia y Alemania para adaptar la música rock’n’roll y acercarla más a sus propios estilos de música y normas societales, como se escucha en los primeros intentos de las respectivas industrias de música en crear sus propias versiones de él. El trabajo aborda estas prácticas, como instancias en los contextos francés, alemán, griego e italiano, de institucionalizar el rock’n’roll de acuerdo con sus propias posiciones frente a Estados Unidos, sus situaciones históricas y políticas y su pasado y presente cultural y musical. Palabras clave: Rock’n’roll, Europe, Guerra Fría, institucionalización, industria de música. American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century) Abstract: This paper assesses the practices developed in France, Italy, Greece, and Germany in order to accommodate rock’n’roll music and bring it closer to their own music styles and societal norms, as these are heard in the initial attempts of their music industries to create their own versions of it. The paper deals with these practices as instances of the French, German, Greek and Italian contexts to institutionalize rock’n’roll according to their positions regarding the USA, their historical and political situations, and their cultural and musical past and present. -

The BG News March 03, 2021

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 3-3-2021 The BG News March 03, 2021 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News March 03, 2021" (2021). BG News (Student Newspaper). 9156. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/9156 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. bg Raisin’ news An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, the Wage ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Wednesday, March 3, 2021 Volume 100, Issue 23 Minimum wage effects on student employees | Page 11 Tree No Leaves Support Volleyball: releases women-owned strong start new album businesses in BG to season Page 5 Page 8 Page 9 PHOTO BY JOSH APPEL VIA UNSPLASH BG-0303-01.indd 1 3/2/21 7:36 PM BG NEWS March 3, 2021 | PAGE 2 Great Selection Close to Campus Great Prices BGSU ON HIGH ALERT JOHN NEWLOVE DHS National Terrorism Announcement REAL ESTATE, INC. Steve Iwanek | Reporter Michigan, and Nation of Islam in Toledo Ohio (not to be mistaken with Masjid of Al- “We are not immune to On Jan. 27 the Department of Homeland Islam Mosque in Toledo). Security announced a domestic terrorism “We are a public institution and people violent behavior in this alert projected to last for weeks. -

Final Version

This research has been supported as part of the Popular Music Heritage, Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity (POPID) project by the HERA Joint Research Program (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, DASTI, ETF, FNR, FWF, HAZU, IRCHSS, MHEST, NWO, RANNIS, RCN, VR and The European Community FP7 2007–2013, under ‘the Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities program’. ISBN: 978-90-76665-26-9 Publisher: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Center for Media, Communication and Culture Printing: Ipskamp Drukkers Cover design: Martijn Koster © 2014 Arno van der Hoeven Popular Music Memories Places and Practices of Popular Music Heritage, Memory and Cultural Identity *** Popmuziekherinneringen Plaatsen en praktijken van popmuziekerfgoed, cultureel geheugen en identiteit Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.A.P Pols and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defense shall be held on Thursday 27 November 2014 at 15.30 hours by Arno Johan Christiaan van der Hoeven born in Ede Doctoral Committee: Promotor: Prof.dr. M.S.S.E. Janssen Other members: Prof.dr. J.F.T.M. van Dijck Prof.dr. S.L. Reijnders Dr. H.J.C.J. Hitters Contents Acknowledgements 1 1. Introduction 3 2. Studying popular music memories 7 2.1 Popular music and identity 7 2.2 Popular music, cultural memory and cultural heritage 11 2.3 The places of popular music and heritage 18 2.4 Research questions, methodological considerations and structure of the dissertation 20 3. The popular music heritage of the Dutch pirates 27 3.1 Introduction 27 3.2 The emergence of pirate radio in the Netherlands 28 3.3 Theory: the narrative constitution of musicalized identities 29 3.4 Background to the study 30 3.5 The dominant narrative of the pirates: playing disregarded genres 31 3.6 Place and identity 35 3.7 The personal and cultural meanings of illegal radio 37 3.8 Memory practices: sharing stories 39 3.9 Conclusions and discussion 42 4. -

ED077069.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 077 069 EA 004 785 AUTHOR Worth, Walter H.,; And Others TITLE A Choice of Futures. INSTITUTION Alberta Commission on Educational Planning, Edmonton. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 337p. AVAIIAELE FROMHurtig Publishers, 225 Birks Building, Edmonton, Alberta (Canada)($6.00, plus mailing) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HCJ$13.16 DESCRIPTORS *Continuous Learning; Economic Factors; Educational Coordination; Educational Finance; Educational Needs; Educational Objectives; *Educational Planning; *Educational Resources; *Futures (of Society); Governance; *Learning Processes; Organization; Prediction; Professional Personnel; Social Problems; Social Structure; Technological Advancement; arend Analysis IDENTIFIERS Alberta; Canada; Experiential Learning ABSTRACT The Commission was commended to investigate social, economic, and technological trends inAlberta for the next 20 years; to examine the needs of all individuals in the Province; to analyze total educational requirements; and to recommend future changes, structures, and priorities necessary for a comprehensive educational system. Between 1969 and 1972, with the help of expert consultants, the Commission sponsored or co-sponsored research studies, held public hearings involving people across the Province, received briefs, convened large conferences, and launched major task force investigations which were made public in 1971. From these resources, the Commission analyzed what people wanted. This analysis resulted in a number of educational ideals, principles, and goals shared by the great majority of citizens, which are presented here. The report also suggests structures, processes, plans, resource management, and priorities designed to help make the good forecasts be true, the bad forecasts be untrue, and the unchangeable forecasts at least tolerable. (Illustrations and photographs may photograph poorly.) (Author) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U.S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. -

Humanism After All? Daft Punk's Existentialist

PARRHESIA NUMBER 8 • 2009 • 76–88 HUMANISM AFTER ALL? DAFT PUNK’S EXISTENTIALIST CRITIQUE OF TRANSHUMANISM Chad Parkhill INTRODUCTION The French dance music production duo Daft Punk have, since the pre-release publicity for their second album, Discovery (2001), used their music (and the accompanying paratexts of video clips, publicity photos, liner notes, and the costume and stage design of their tours) as an occasion to meditate on the relationship between technology and the human. Although their early efforts at exploring this relationship seem at best naïve—they initially claimed that an accident in their recording studio in September 1999 had transformed them into robots1—their later texts, such as the video clips that accompany their third album, Human After All (2005), display an increasing level of sophistication, not only in artistic but also in philosophical terms. Despite the fact that their music and its commercial success rely extensively on technologies of sound manipulation, digital reproduction, and new forms of online media, Daft Punk’s recent examinations of the relationship between technology and the human are, to say the least, ambivalent. On the one hand, songs such as “Technologic” can be read as paeans to the possibilities that technology opens up to human existence, and the fact that the song was swiftly seized upon by advertising executives to sell Apple’s iPod music player would support such a reading. On the other hand, the visual codes and semiotics of the song’s video clip suggest that Daft Punk’s vision of the technological is a much darker one than Apple might like to embrace.2 Nowhere else in the duo’s oeuvre is their take on technology and the human more developed in its details and more ambivalent in its message than in their debut feature-length film, Electroma (2007). -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

DJ – Titres Incontournables

DJ – Titres incontournables Ce listing de titres constamment réactualisé , il vous ait destiné afin de surligner avec un code couleur ce que vous préférez afin de vous garantir une personnalisation totale de votre soirée . Si vous le souhaitez , il vaut mieux nous appeler pour vous envoyer sur votre mail la version la plus récente . Vous pouvez aussi rajouter des choses qui n’apparaissent pas et nous nous chargeons de trouver cela pour vous . Des que cette inventaire est achevé par vos soins , nous renvoyer par mail ce fichier adapté à vos souhaits 2018 bruno mars – finesse dj-snake-magenta-riddim-audio ed-sheeran-perfect-official-music-video liam-payne-rita-ora-for-you-fifty-shades-freed luis-fonsi-demi-lovato-echame-la-culpa ofenbach-vs-nick-waterhouse-katchi-official-video vitaa-un-peu-de-reve-en-duo-avec-claudio-capeo-clip-officiel 2017 amir-on-dirait april-ivy-be-ok arigato-massai-dont-let-go-feat-tessa-b- basic-tape-so-good-feat-danny-shah bastille-good-grief bastille-things-we-lost-in-the-fire bigflo-oli-demain-nouveau-son-alors-alors bormin-feat-chelsea-perkins-night-and-day burak-yeter-tuesday-ft-danelle-sandoval calum-scott-dancing-on-my-own-1-mic-1-take celine-dion-encore-un-soir charlie-puth-attention charlie-puth-we-dont-talk-anymore-feat-selena-gomez clean-bandit-rockabye-ft-sean-paul-anne-marie dj-khaled-im-the-one-ft-justin-bieber-quavo-chance-the-rapper-lil-wayne dj-snake-let-me-love-you-ft-justin-bieber enrique-iglesias-subeme-la-radio-remix-remixlyric-video-ft-cnco feder-feat-alex-aiono-lordly give-you-up-feat-klp-crayon -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Download Download

Journal of Mason Graduate Research Volume 2 Number 2 Year 2015 © George Mason University, Fairfax, VA ISSN: 2327-0764 Pages: 56-66 Here and Nowhere, A Critical Analysis of Geomusicology BRITNAE A. PURDY George Mason University Geomusicology, the study of the geography of music, encompasses themes such as patriotism, politics, sense of identity, history, ethnicity, and more, making it a crucial, if often overlooked component of geopolitics. As a relatively new field of research, geomusicology warrants more attention to determine its ability to contribute to geopolitics. However, the major themes of the field are at times contradictory and abstract, calling for a subtle and nuanced understanding of research in the field. This paper provides an overview of some major literature in geomusicology and concludes that most researchers in the field believe that music is both anchored by place and universal at the same time. Using a critical approach to geopolitics, this paper thus debates the strengths and weakness of geomusicology with recommendations on how to further evolve the field to contribute to a fuller understanding of geopolitics as a whole. Here and Nowhere Geomusicology, the study of the geography of music, tackles many difficult concepts. As an auditory unit, music itself cannot be physically constrained and its message can often be considered universal. However, in the sense that music is produced and performed in a physical space, and to the extent that music is shaped by the socio-economic, political, cultural, and physical landscape of its origin, it is also inherently geopolitical. The literature concerning geomusicology addresses both of these ideas, creating an inherently critical discourse on geography and music that can appear to be both contradictory and complementary. -

Stan Magazynu Caĺ†Oĺıäƒ Lp Cd Sacd Akcesoria.Xls

CENA WYKONAWCA/TYTUŁ BRUTTO NOŚNIK DOSTAWCA ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST 159,99 SACD BERTUS ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - AT FILLMORE EAST (NUMBERED 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - BROTHERS AND SISTERS (NUMBE 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - EAT A PEACH (NUMBERED LIMIT 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - IDLEWILD SOUTH (GOLD CD) 129,99 CD GOLD MOBILE FIDELITY ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY ASIA - ASIA 179,99 SACD BERTUS BAND - STAGE FRIGHT (HYBRID SACD) 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - MUSIC FROM BIG PINK (NUMBERED LIMITED 89,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BAND, THE - THE LAST WALTZ (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITI 179,99 2 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BASIE, COUNT - LIVE AT THE SANDS: BEFORE FRANK (N 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY BIBB, ERIC - BLUES, BALLADS & WORK SONGS 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - JUST LIKE LOVE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC - RAINBOW PEOPLE 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - GOOD STUFF 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BIBB, ERIC & NEEDED TIME - SPIRIT & THE BLUES 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 BLIND FAITH - BLIND FAITH 159,99 SACD BERTUS BOTTLENECK, JOHN - ALL AROUND MAN 89,99 SACD OPUS 3 CAMEL - RAIN DANCES 139,99 SHMCD BERTUS CAMEL - SNOW GOOSE 99,99 SHMCD BERTUS CARAVAN - IN THE LAND OF GREY AND PINK 159,99 SACD BERTUS CARS - HEARTBEAT CITY (NUMBERED LIMITED EDITION HY 149,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS AFTER HOURS (NUMBERED LI 99,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY CHARLES, RAY - THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES (NUMBERED 129,99 SACD MOBILE FIDELITY