Jesso, Leo Francis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RISQUES ET NUISANCES Profil Thématique V1

RISQUES ET NUISANCES Profil thématique V1 Octobre 2014 BAVELINCOURT BEAUCOURT-SUR-L’HALLUE BEHENCOURT CARDONNETTE COISY CONTAY FLESSELLES FRECHENCOURT LA VICOGNE MIRVAUX MOLLIENS AU BOIS MONTIGNY SUR L’HALLUE MONTONVILLERS NAOURS PIERREGOT PONT-NOYELLE QUERRIEU RAINNEVILLE RUBEMPRE SAINT-GRATIEN SAINT-VAST-EN-CHAUSSEE TALMAS VADENCOURT VAUX EN AMIENOIS VILLERS-BOCAGE WARGNIES SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION p. 2 QUESTION 1 p. 3 > Quels sont les risques naturels de Bocage-Hallue ? ZOOM SUR…L’ETUDE « BASSIN VERSANT » DE NAOURS et WARGNIES ET DE MONTONVILLERS p. 23 QUESTION 2 p. 16 > Quels sont les risques industriels, les pollutions et les nuisances de Bocage-Hallue ? ZOOM SUR… L’IMPORTANCE DE L’ACTIVITÉ AGRICOLE DANS LA GESTION DES RISQUES NATURELS p. 23 DES CLÉS POUR LE PROJET p. 24 REGARDS D’ACTEURS p. 25 > Les profils thématiques sont les 1ers documents livrés aux élus dans la cadre du diagnostic territorial. Ils ont pour vocation de partager largement, jusqu’aux conseils municipaux, les grandes caractéristiques de Bocage- Hallue . Ils préparent ainsi le travail de synthèse nécessaire pour finaliser le diagnostic. Transversale aux différents thèmes, cette synthèse aboutira à la sélection des enjeux territoriaux supports du futur projet d’aménagement et de développement durables. INTRODUCTION Les documents d’urbanisme doivent permettre le développement des activités humaines tout en préservant les populations des risques naturels, technologiques et des nuisances. Les élus locaux sont ainsi les garants de la sécurité et du bien-être de leurs concitoyens. En application de l’article L121-1 du Code de l’Urbanisme, les plans locaux d'urbanisme déterminent les conditions permettant d'assurer, dans le respect des objectifs du développement durable, la prévention des risques naturels prévisibles, des risques miniers, des risques technologiques, des pollutions et des nuisances de toute nature. -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs

RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS Numéro 33 1er juillet 2010 RECUEIL des ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS N° 33 du 1er juillet 2010 SOMMAIRE ARRÊTÉS DU PRÉFET DE DÉPARTEMENT BUREAU DU CABINET Objet : Liste des établissements recevant du public et immeuble de grande hauteur implantés dans la Somme au 31 décembre 2009 et soumis aux dispositions du règlement de sécurité contre les risques d'incendie et de panique-----1 Objet : Médaille d’honneur agricole-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------1 Objet : Médaille d’honneur régionale, départementale et communale--------------------------------------------------------6 Objet : délégation de signature : cabinet-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------27 Objet : délégation de signature : permanences des sous-préfets et du secrétaire général pour les affaires régionales 28 DIRECTION DES AFFAIRES JURIDIQUES ET DE L'ADMINISTRATION LOCALE Objet : CNAC du 8 avril 2010 – création d'un ensemble commercial à VILLERS-BRETONNEUX------------------29 DIRECTION DÉPARTEMENTALE DES TERRITOIRES ET DE LA MER DE LA SOMME Objet : Règlement intérieur de la Commission locale d’amélioration de l’habitat du département de la Somme-----30 Objet : Arrêté portant sur la régulation des blaireaux--------------------------------------------------------------------------31 Objet : Arrêté fixant la liste des animaux classés nuisibles et fixant les modalités de destruction à tir pour la période du 1er juillet 2010 au 30 juin 2011 pour le -

Balsom, Ralph Norman

Sergeant Ralph Norman Balsom (Regimental Number 2395) is interred in Passchendaele New British Cemetery – Grave reference XI. A. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a railway conductor working for the Reid Newfoundland Company and earning a monthly sixty-five dollars, Ralph Norman Balsom was a volunteer of the Ninth Recruitment Draft. He presented himself for medical examination on March 31 of 1916 at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland. It was a procedure which was to pronounce him as…Fit for Foreign Service. (continued) 1 Three days after that medical assessment, on April 3, and at the same venue, Ralph Norman Balsom would enlist, and was engaged…for the duration of the war*…at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to be appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. *At the outset of the War, perhaps because it was felt by the authorities that it would be a conflict of short duration, the recruits enlisted for only a single year. As the War progressed, however, this was obviously going to cause problems and the men were encouraged to re-enlist. Later recruits – as of or about May of 1916 - signed on for the ‘Duration’ at the time of their original enlistment. It was then only a matter of hours before there then came to pass, once more at the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road, the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same April 3 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, whereupon, at that moment, Ralph Norman Balsom became…a soldier of the King. -

1081W SDIS (Service Départemental De Protection Contre L'incendie)

DÉPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME CONSEIL DÉPARTEMENTAL ARCHIVES DÉPARTEMENTALES FONDS DE LA PRÉFECTURE DE LA SOMME 1ère Division – 2e Bureau _______ Service départemental de protection contre l'incendie 1873-1984 Répertoire numérique détaillé 1081 W réalisé par Inès GUERIN, Attachée d'administration, Morgan MAZURIER, conditionnement, sous le contrôle scientifique de Arnaud ESPEL, Attaché de conservation du patrimoine, et sous la direction de Elise BOURGEOIS, Conservatrice du patrimoine, directrice adjointe Amiens, 2018 Sommaire Introduction page 3 Présentation du versement Intérêt historique du versement Communicabilité Bibliographie et sources complémentaires page 6 Répertoire numérique détaillé page 12 Administration générale Fonctionnement Finances page 13 Personnel Dossiers techniques page 14 Sécurité Centres de secours municipaux page 31 Table de concordance page 33 - 2 - INTRODUCTION PRÉSENTATION DU VERSEMENT Le versement 1081W a été réalisé le 18 octobre 1984 par le service de secours et d'incendie de la Préfecture de la Somme. Ce service est devenu aujourd’hui le service départemental d’incendie et de secours (SDIS), financé en majorité par le Conseil départemental. La description des liasses et la rédaction du bordereau de versement initial résultent d’un récolement succinct opéré par les agents des Archives départementales lors de l’arrivée des documents. Composé à l’origine de 571 articles et de 48 mètres linéaires puis réduit à 7 mètres linéaires après classement et élimination des doublons, ce versement a fait l'objet d'un premier tri en 1997 donnant lieu à l'élimination de 403 articles (achat de matériel, médaille d'honneur, financement d’événements, examen d'aptitude, allocation de vétérans, rapport d'opération, contrats d'assurance, fiches de renseignements sur le personnel, pièces financières). -

1 Private Heber Trask, MM, (Regimental Number 3156)

Private Heber Trask, MM, (Regimental Number 3156), having no known last resting-place, is commemorated on the bronze beneath the Caribou in the Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont- Hamel. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a wood-barker/ millman earning a daily $1.80, and being employed by the Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company in Grand Falls, Heber Trask was a volunteer of the Twelfth Recruitment Draft. He presented himself for medical examination on October 16 of 1916 at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury* in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland. It was a procedure which was to pronounce him as…Fit for Foreign Service. *The building was to serve as the Regimental Headquarters in Newfoundland for the duration of the conflict. It was to be on the day of that medical assessment, October 16, and at the same venue, that Heber Trask would enlist. He was thus engaged…for the duration of the war*…at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to be appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. *At the outset of the War, perhaps because it was felt by the authorities that it would be a conflict of short duration, the recruits enlisted for only a single year. As the War progressed, however, this was obviously going to cause problems and the men were encouraged to re-enlist. Later recruits – as of or about May of 1916 - signed on for the ‘Duration’ at the time of their original enlistment. Only a few further hours were now to follow before there then came to pass, while still at the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road, the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. -

Mairie-École De Coisy

Hauts-de-France, Somme Coisy 10 rue Manon-Lescaut Mairie-école de Coisy Références du dossier Numéro de dossier : IA80000235 Date de l'enquête initiale : 1998 Date(s) de rédaction : 1998 Cadre de l'étude : inventaire topographique canton de Villers-Bocage Degré d'étude : étudié Désignation Dénomination : mairie, école Parties constituantes non étudiées : logement, dépendance Compléments de localisation Milieu d'implantation : en village Références cadastrales : 1932, A2, 79 Historique Une première école est établie en 1823 dans l'étable du presbytère, bâtiment en torchis pourvu d'une cheminée, de deux portes et de deux fenêtres (devis dressé par Antoine Sauvé et Casimir Dupont, charpentiers à Allonville). A la suite d'un incendie en 1839, la commune doit la reconstruire. En 1882 cette école est jugée insuffisante : elle ne comporte qu'une seule pièce, humide et mal éclairée, sans logement pour l'instituteur. Un nouveau projet de mairie-école est alors établi par l'architecte amiénois Paul Delefortrie (dont le père avait reconstruit l'église de Coisy en 1853). Les travaux, exécutés par Mercier, entrepreneur à Vignacourt, sur un emplacement voisin de l'ancienne école, sont achevés en 1884 pour un coût d'environ 30 000 francs. L'un des vestiaires qui flanquaient la salle de classe a été abattu en 1998. Période(s) principale(s) : 4e quart 19e siècle Dates : 1884 (porte la date, daté par source) Auteur(s) de l'oeuvre : Paul Jules Joseph Delefortrie (architecte, attribution par source), Mercier (entrepreneur, attribution par source) Description Face à la rue, s'élève un grand bâtiment à étage-carré servant de mairie et de logement d'instituteur. -

Topics 20121Q1

third quarter ● 2014 T pics Whole number 540 Volume 71 Number 3 Canada’s WWI Monument at Vimy Ridge Newfoundland’s WWI Monument at Beaumont-Hamel Memorial Issue: 100th Anniversary of the beginning of World War I The official Journal of BNAPS The Society for Canadian Philately $8.95 1 BNA Topics, Volume 71, Number 3, July–September 2014 2 BNA T pics Volume 71 Number 3 Whole Number 540 The Official Journal of the British North America Philatelic Society Ltd Contents 3 Editorial 4 Readers write 6 Canadian military hospitals at sea 1914–1919........................................................................... Jonathan C Johnson, OTB 11 WWI War Savings stamps and promotions...................................................................................................David Bartlet 20 Newfoundland and the Great War Part 1: Preparations..................................................... CR McGuire, OTB FRPSC 32 Destination: HOLLAND (Escape from Germany) ................................................................................J Michael Powell 38 An overview of World War I patriotic flag cancels .......................................................Douglas Lingard, OTB, FRPSC 46 WWI-era Canadian Cinderella stamps .......................................................................................Ronald G Lafrenière, PhD 54 Fiscal War Tax stamps of World War I............................................................................................................... John Hall 64 Newfoundland: The “Trail of the Caribou” -

Rankings Municipality of Coisy TREND N ° FAMILY MEMBERS

10/1/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links FRANCIA / HAUTS DE FRANCE / Province of SOMME / Coisy Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH FRANCIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Abbeville Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Équennes- AdminstatAblaincourt- logo Éramecourt DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Pressoir FRANCIA Erches Acheux- en-Amiénois Ercheu Acheux- Ercourt en-Vimeu Ergnies Agenville Érondelle Agenvillers Esclainvillers Aigneville Esmery-Hallon Ailly-le-Haut- Essertaux Clocher Estrébouf Ailly-sur-Noye Estrées- Ailly-sur-Somme Deniécourt Airaines Estrées-lès-Crécy Aizecourt-le-Bas Estrées-Mons Aizecourt- Estrées-sur-Noye le-Haut Étalon Albert Ételfay Allaines Éterpigny Allenay Étinehem- Allery Méricourt Allonville Étréjust Amiens Étricourt- Andainville Manancourt Andechy Falvy Argoules Famechon Argouves Faverolles Arguel Favières Armancourt Fay Arquèves Ferrières Arrest Fescamps Arry Feuillères Arvillers Feuquières- en-Vimeu Assainvillers Fieffes- Assevillers Montrelet Athies Fienvillers Aubercourt Fignières Aubigny Fins Aubvillers Flaucourt Auchonvillers Flers Ault Flers-sur-Noye Powered by Page 3 Aumâtre Flesselles L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Provinces Aumont Fleury Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Autheux FRANCIAFlixecourt Authie -

La Région D'amiens

La région d’Amiens Nicolas Bernigaud, Lydie Blondiau, Stéphane Gaudefroy, Sébastien Lepetz, Christophe Petit, Véronique Zech-Matterne, Laurent Duvette To cite this version: Nicolas Bernigaud, Lydie Blondiau, Stéphane Gaudefroy, Sébastien Lepetz, Christophe Petit, et al.. La région d’Amiens. Michel Reddé. Gallia Rustica 1. Les campagnes du nord-est de la Gaule, de la fin de l’âge du Fer à l’Antiquité tardive, 1 (49), Ausonius éditions, pp.179-210, 2017, Mémoires, 978-2-35613-206-2. hal-03029584 HAL Id: hal-03029584 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03029584 Submitted on 28 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Chapitre 7 La région d’Amiens Nicolas Bernigaud, Lydie Blondiau, Stéphane Gaudefroy, Sébastien Lepetz, Christophe Petit et Véronique Zech-Matterne avec la collaboration de Laurent Duvette I ntroduction (NB) Divisée en trois départements (Aisne, Oise, Somme), l’ancienne région administrative de Picardie couvre une superficie de près 13 400 km2, soit environ 7 % de l’aire étudiée dans le cadre du projet RurLand. Pendant la période romaine, cette partie de la Gaule Belgique était occupée par plusieurs peuples, notamment les Ambiens, les Viromanduens, les Bellovaques, les Silvanectes, les Suessions, dont Amiens, Saint-Quentin, Beauvais, Senlis et Soissons étaient respectivement les capitales. -

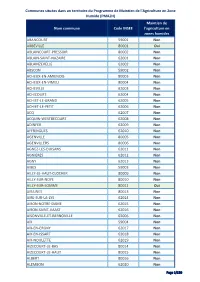

(PMAZH) Nom Commune Code INSEE

Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ABANCOURT 59001 Non ABBEVILLE 80001 Oui ABLAINCOURT-PRESSOIR 80002 Non ABLAIN-SAINT-NAZAIRE 62001 Non ABLAINZEVELLE 62002 Non ABSCON 59002 Non ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 Non ACHEUX-EN-VIMEU 80004 Non ACHEVILLE 62003 Non ACHICOURT 62004 Non ACHIET-LE-GRAND 62005 Non ACHIET-LE-PETIT 62006 Non ACQ 62007 Non ACQUIN-WESTBECOURT 62008 Non ADINFER 62009 Non AFFRINGUES 62010 Non AGENVILLE 80005 Non AGENVILLERS 80006 Non AGNEZ-LES-DUISANS 62011 Non AGNIERES 62012 Non AGNY 62013 Non AIBES 59003 Non AILLY-LE-HAUT-CLOCHER 80009 Non AILLY-SUR-NOYE 80010 Non AILLY-SUR-SOMME 80011 Oui AIRAINES 80013 Non AIRE-SUR-LA-LYS 62014 Non AIRON-NOTRE-DAME 62015 Non AIRON-SAINT-VAAST 62016 Non AISONVILLE-ET-BERNOVILLE 02006 Non AIX 59004 Non AIX-EN-ERGNY 62017 Non AIX-EN-ISSART 62018 Non AIX-NOULETTE 62019 Non AIZECOURT-LE-BAS 80014 Non AIZECOURT-LE-HAUT 80015 Non ALBERT 80016 Non ALEMBON 62020 Non Page 1/130 Communes situées dans un territoire du Programme de Maintien de l'Agriculture en Zone Humide (PMAZH) Maintien de Nom commune Code INSEE l'agriculture en zones humides ALETTE 62021 Non ALINCTHUN 62022 Non ALLAINES 80017 Non ALLENAY 80018 Non ALLENNES-LES-MARAIS 59005 Non ALLERY 80019 Non ALLONVILLE 80020 Non ALLOUAGNE 62023 Non ALQUINES 62024 Non AMBLETEUSE 62025 Oui AMBRICOURT 62026 Non AMBRINES 62027 Non AMES 62028 Non AMETTES 62029 Non AMFROIPRET 59006 Non AMIENS 80021 Oui AMPLIER 62030 Non AMY -

PROCES-VERBAL Conseil Communautaire Du Jeudi 04 Juillet

PROCES-VERBAL Conseil communautaire du jeudi 04 juillet 2019 18 heures – Espace culturel de Doullens Page 1 sur 73 COMPOSITION Le Président Monsieur Laurent SOMON Bernaville 1er Vice-président Monsieur Claude DEFLESSELLE Coisy En charge de l’économie et des finances 2e Vice-président Monsieur Christian VLAEMINCK Doullens En charge des bâtiments 3e Vice-président Monsieur Jean-Michel MAGNIER Beaumetz En charge du scolaire 4e Vice-président Monsieur Jean-Michel BOUCHY Naours En charge du tourisme 5e Vice-président Monsieur Francis PETIT Grouches-Luchuel En charge de la GEMAPI 6e Vice-président Monsieur Daniel POTRIQUIER Bonneville En charge de l’eau et l’assainissement 7e Vice-président Monsieur Laurent CRAMPON Montonvillers En charge de l’enfance et la jeunesse 8e Vice-président Monsieur François DURIEUX Beauquesne En charge de l’urbanisme et de la planification 9e Vice-président Monsieur Patrick BLOCKLET Talmas En charge de la voirie 10e Vice-présidente Madame Christelle HIVER Doullens En charge du personnel 11e Vice-président Monsieur Dominique HERSIN Candas En charge du social 12e Vice-présidente Madame Anne-Sophie DOMONT Villers-Bocage En charge de la culture 13e Vice-présidente Madame Catherine PENET-CARON Humbercourt En charge de l’insertion Membres du Bureau communautaire : 1. Monsieur Frédéric AVISSE Molliens-au-Bois 2. Monsieur Jean Pierre DOMONT Villers-Bocage 3. Madame Annie MARCHAND Beaucourt-sur-l’Hallue 4. Monsieur Philippe PLAISANT Béhencourt 5. Monsieur Jean-Marie ROUSSEAUX Rubempré 6. Monsieur Bernard THUILLIER Beauval 7. Monsieur François CREPIN Longuevillette 8. Monsieur Alain CHEVALIER Gézaincourt 9. Monsieur Pascal PIOT Doullens 10. Monsieur William NGASSAM Doullens 11. Monsieur Dany CHOQUET Heuzecourt 12. -

Votre Hebdomadaire Dans La Somme

Votre hebdomadaire dans la Somme Fort-Mahon- Le Journal d'Abbeville Plage Nampont Argoules Parution : mercredi Dominois Quend Villers- sur-Authie Vron Ponches- Estruval Vercourt Vironchaux Dompierre- Saint- Regnière- sur- Quentin- Ecluse Ligescourt Authie en-Tourmont Arry Rue Machy Machiel Bernay- Le Boisle en-Ponthieu Estrées- Boufflers lès-Crécy Le Forest- Vitz- Crotoy Montiers Crécy- sur-Authie en-Ponthieu Fontaine- Gueschart Favières sur-Maye Brailly- Cornehotte Neuilly- Froyelles le-Dien Ponthoile Bouquemaison Nouvion Noyelles- Maison- Frohen- Brévillers Forest- en-Chaussée Ponthieu le-Grand l'Abbaye Humbercourt Domvast Béalcourt Remaisnil Barly Neuvillette Hiermont Maizicourt Saint- Noyelles- Frohen- Lucheux Lamotte- Canchy Acheul Saint- sur-Mer Le Titre Bernâtre le-Petit Lanchères Buleux Yvrench Grouches- Gapennes Montigny- Luchuel Valéry- Sailly- Conteville Mézerolles Occoches Flibeaucourt Agenvillers les-Jongleurs Le sur-Somme Hautvillers- Neuilly- Yvrencheux Agenville Meillard Cayeux- Ouville l'Hôpital Outrebois sur-Mer Pendé Boismont Domléger- Heuzecourt Doullens Port-le-Grand Buigny- Longvillers Estrébœuf Saint- Millencourt- Oneux Boisbergues Hem- Cramont Prouville Hardinval Maclou Drucat en-Ponthieu Brutelles Saigneville Coulonvillers Authieule Saint- Autheux Gézaincourt Grand- Mesnil- Beaumetz Blimont Arrest Caours Maison- Bernaville Mons- Laviers Saint- Domqueur Saint- Bayencourt Boubert Roland Longuevillette Woignarue Riquier Domesmont Authie Léger- Cahon Neufmoulin lès- Coigneux Vaudricourt Ribeaucourt Fienvillers Quesnoy-