The Deaths of Four Consular Officials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

Harvest Records Discography

Harvest Records Discography Capitol 100 series SKAO 314 - Quatermass - QUATERMASS [1970] Entropy/Black Sheep Of The Family/Post War Saturday Echo/Good Lord Knows/Up On The Ground//Gemini/Make Up Your Mind/Laughin’ Tackle/Entropy (Reprise) SKAO 351 - Horizons - The GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH [1970] Again And Again/Angelina/Day Of The Lady/Horizons/I Fought For Love/Real Cool World/Skylight Man/Sunflower Morning [*] ST 370 - Anthems In Eden - SHIRLEY & DOROTHY COLLINS [1969] Awakening-Whitesun Dance/Beginning/Bonny Cuckoo/Ca’ The Yowes/Courtship-Wedding Song/Denying- Blacksmith/Dream-Lowlands/Foresaking-Our Captain Cried/Gathering Rushes In The Month Of May/God Dog/Gower Wassail/Leavetaking-Pleasant And Delightful/Meeting-Searching For Lambs/Nellie/New Beginning-Staines Morris/Ramble Away [*] ST 371 - Wasa Wasa - The EDGAR BROUGHTON BAND [1969] Death Of An Electric Citizen/American Body Soldier/Why Can’t Somebody Love You/Neptune/Evil//Crying/Love In The Rain/Dawn Crept Away ST 376 - Alchemy - THIRD EAR BAND [1969] Area Three/Dragon Lines/Druid One/Egyptian Book Of The Dead/Ghetto Raga/Lark Rise/Mosaic/Stone Circle [*] SKAO 382 - Atom Heart Mother - The PINK FLOYD [1970] Atom Heart Mother Suite (Father’s Shout-Breast Milky-Mother Fore-Funky Dung-Mind Your Throats Please- Remergence)//If/Summer ’68/Fat Old Sun/Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast (Rise And Shine-Sunny Side Up- Morning Glory) SKAO 387 - Panama Limited Jug Band - PANAMA LIMITED JUG BAND [1969] Canned Heat/Cocaine Habit/Don’t You Ease Me In/Going To Germany/Railroad/Rich Girl/Sundown/38 -

APPENDIX Radio Shows

APPENDIX Radio Shows AAA Radio Album Network BBC Cahn Media Capital Radio Ventures Capitol EMI Global Satellite Network In The Studio (Album Network / SFX / Winstar Radio Services / Excelsior Radio Networks / Barbarosa) MJI Radio Premiere Radio Networks Radio Today Entertainment Rockline SFX Radio Network United Stations Up Close (MCA / Media America Radio / Jones Radio Network) Westwood One Various Artists Radio Shows with Pink Floyd and band members PINK FLOYD CD DISCOGRAPHY Copyright © 2003-2010 Hans Gerlitz. All rights reserved. www.pinkfloyd-forum.de/discography [email protected] This discography is a reference guide, not a book on the artwork of Pink Floyd. The photos of the artworks are used solely for the purposes of distinguishing the differences between the releases. The product names used in this document are for identification purposes only. All trademarks and registered trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Permission is granted to download and print this document for personal use. Any other use including but not limited to commercial or profitable purposes or uploading to any publicly accessibly web site is expressly forbidden without prior written consent of the author. APPENDIX Radio Shows PINK FLOYD CD DISCOGRAPHY PINK FLOYD CD DISCOGRAPHY APPENDIX Radio Shows A radio show is usually a one or two (in some cases more) hours programme which is produced by companies such as Album Network or Westwood One, pressed onto CD, and distributed to their syndicated radio stations for broadcast. This form of broadcasting is being used extensively in the USA. In Europe the structure of the radio stations is different, the stations are more locally oriented and the radio shows on CDs are very rare. -

PINK FLOYD ‘The Early Years 1965-1972’ Released: 11 November 2016

** NEWS ** ISSUED: 28.07.16 STRICTLY EMBARGOED UNTIL: 14:00HRS BST, THURSDAY 28 JULY 2016 PINK FLOYD ‘The Early Years 1965-1972’ Released: 11 November 2016 • Unreleased demos, TV appearances and live footage from the Pink Floyd archives • 6 volumes plus a bonus EXCLUSIVE ‘Extras’ package across 27 discs • Over 20 unreleased songs including 1967’s Vegetable Man and In the Beechwoods • Remixed and updated versions of the music from ‘Zabriskie Point’ • 7 hours of previously unreleased live audio • 15 hours 35 mins of video including rare concert performances, interviews and 3 feature films * 2 CD selection set ‘The Early Years – CRE/ATION’ also available * On 11 November 2016, Pink Floyd will release ‘The Early Years 1965-1972’. Pink Floyd have delved into their vast music archive, back to the very start of their career, to produce a deluxe 27-disc boxset featuring 7 individual book-style packages, including never before released material. The box set will contain TV recordings, BBC Sessions, unreleased tracks, outtakes and demos over an incredible 12 hours, 33 mins of audio (made up of 130 tracks) and over 15 hours of video. Over 20 unreleased songs including 7 hours of previously unreleased live audio, plus more than 5 hours of rare concert footage are included, along with meticulously produced 7” singles in replica sleeves, collectable memorabilia, feature films and new sound mixes. Previously unreleased tracks include 1967’s Vegetable Man and In The Beechwoods which have been newly mixed for the release. ‘The Early Years 1965-1972’ will give collectors the opportunity to hear the evolution of the band and witness their part in cultural revolutions from their earliest recordings and studio sessions to the years prior to the release of ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’, one of the biggest selling albums of all time. -

Þáttur 5.Odt

Biding My Time Good afternoon. My name is Björgvin Rúnar Leifsson and this is an episode about Pink Floyd. The song we heard in the beginning is called "Biding My Time". Roger Waters wrote it in 1969 but it did not appear on an album until the compilation album "Relics", which was released in May 1971 and contained various songs from 1967- 69. The song is a characteristic Waters' ballad as they were during these years but it also has some bluesy tint. But let's turn to Pink Floyd's composition in 1971. They went into the studio early this year with all sorts of ideas but had a hard time bringing them together. Among the things they tried was that each of them recorded their own channel around a certain basic theme regardless of what the others were doing. Furthermore, they continued experimenting with all sorts of effects and synthesizers and they were actually among the very first bands to use the famous Moog synthesizer. Also, they were not afraid to try all kinds of sounds, both from nature and man- made environment. It's enough to mention the bird sounds on "Grantchester Meadows" on "Ummagumma" and diverse kitchen sounds in "Alan's Psychedelic Breakfast" on "Atom Heart Mother". In fact, after "Dark Side of the Moon" was released, they had an idea for an album, which would be exclusively kitchen sounds, such as plates, glasses and cutlery, but they gave up on the idea although they actually took advantage of some parts of these experiments on some albums later, such as "Wish You Were Here". -

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

1969 DRAMATIS/ATION 2 X CD / 1 X DVD / 1 X Blu-Ray

PINK FLOYD THE EARLY YEARS 1969 DRAMATIS/ATION 2 x CD / 1 x DVD / 1 x Blu-ray ...................................................................................................................................................... CD 1: PFREY3CD1 Alternative versions from ‘More’ album 1. Hollywood – non album track 1.21 2. Theme (Beat version) (Alternative version) 5.38 3. More Blues (Alternative version) 3.49 4. Seabirds (Instrumental) – non album track 4.20 5. Embryo (from ‘Picnic’) 4.43 BBC Session, 12 May 1969 6. Grantchester Meadows 3.46 7. Cymbaline BBC Session, 12 May 1969 3.38 8. The Narrow Way 4.48 9. Green Is The Colour / BBC Session, 12 May 3.23 10.Careful With That Axe, Eugene 3.27 Live at the Paradiso, Amsterdam, 9 Aug 1969 11. Interstellar Overdrive 4.15 12. Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun 12.25 13. Careful With That Axe, Eugene 10.09 14. A Saucerful Of Secrets 13.0 (NB: vocal mics failed, so all-instrumental set) Total 78.50 mins approx. Tracks 1-4, 6-14 released in 2016 for the first time CD 2: Live PFREY3CD2 ‘The Man’ and ‘The Journey’, performed at the Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, 17 Sept 1969 Part 1, The Man 1. Daybreak (Grantchester Meadows) 8.14 2. Work 4.12 3. Afternoon (Biding My Time) 6.39 4. Doing It 3.54 5. Sleeping 4.38 6. Nightmare (Cymbaline) 9.15 7. Labyrinth 1.10 Part 2, The Journey 8. The Beginning (Green Is The Colour) 3.25 9. Beset By Creatures Of The Deep (Careful With That Axe, Eugene) 6.27 10. The Narrow Way, Part 3 5.11 11. -

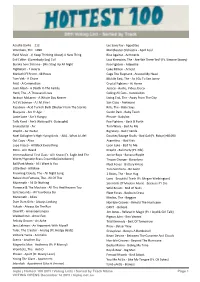

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

Boustrophedon

Gregory J. Markopoulos BOUSTROPHEDON Temenos Gregory J. Markopoulos 1977. All rights reserved LOVE'S TASK I When a film is born all the energies of Nature conspire in holy eleison of praise that they have been subdued in Love's Task. The trees, if it be the season of Fall, radiate in supernal colors; blushing to red, the symbol of chained passions released; to yellow, the symbol of ancient priestly duties attended, miraculously achieved; into blue, the protecting, evasive Alliance, like a wall created of slabs of Egyptian granite, made fearful for unlawful intruders; into green, the eternal mantel woven by Merlin which forever, invisibly nourishes the working needs of him who is the master filmmaker. A master filmmaker appears because the winds, which are the pulsing breakers of his soul, impose upon him, the filmmaker, an unsought, evocative urge, which is Filmmaking. The voice of this Filmmaking springs like a mountain spring from sources unknown, in the beginning to the filmmaker. But if he is truly the son of the immoveable winds that have stirred in him the work, he will proceed from film to film, opposed only by human contacts; human contacts which unaware of the giant soul before them, may attempt in their ignorance to dispossess the filmmaker charms and discharms that emanate from him. But again, if a filmmaker is truly a filmmaker, he will have the knowledge which one could state as being that of Matter and Anti-Matter. He possesses that mirror which presents for him: (a) what is seen, (b) what is not seen, (c) the opposite of what is seen, (d) the opposite of what is not seen. -

2 Column Indented

Music By Bonnie 25,000 Karaoke Songs ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years 20 Fingers Actions & Motives 29768 Short Dick Man 1962 Beautiful 29769 Drug Of Choice 29770 3 Doors Down Fix Me 29771 Away From The Sun 6184 Shoot It Out 29772 Be Like That 6185 Through The Iris 20005 Behind Those Eyes 13522 Wasteland 16042 Better Life, The 17627 Citizen Soldier 17628 10,000 Maniacs Duck And Run 6188 Because The Night 1750 Every Time You Go 25704 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Here By Me 17629 Like The Weather 16149 Here Without You 13010 More Than This 16150 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 These Are The Days 1273 Kryptonite 6190 Trouble Me 16151 Landing In London 17631 100 Proof Aged In Soul Let Me Be Myself 25227 Somebody's Been Sleeping In My Bed 27746 Let Me Go 13785 Live For Today 13648 10cc Loser 6192 Donna 20006 Road I'm On, The 6193 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 So I Need You 17632 I'm Mandy 16152 When I'm Gone 13086 I'm Not In Love 2631 When You're Young 25705 Rubber Bullets 20007 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 3 Inches Of Blood Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Deadly Sinners 27748 112 30 Seconds To Mars Come See Me 25019 Closer To The Edge 26358 Dance With Me 22319 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 It's Over Now 22320 Kings And Queens 26359 Peaches & Cream 22321 311 U Already Know 13602 All Mixed Up 16156 12 Stones Don't Tread On Me 13649 We Are One 27248 Down 27749 First Straw 22322 1975, The Love Song 22323 Love Me 29773 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Sound, The 29774 UGH! 29775 36 Crazyfists Bloodwork 29776 2 Chainz Destroy The Map 29777 Spend It 25701 Great Descent, The 29778 2 Live Crew Midnight Swim 29779 Do Wah Diddy 25702 Slit Wrist Theory 29780 Me So Horny 27747 38 Special We Want Some PuXXy 25703 Caught Up In You 1904 2 Pistols (ft. -

Pink Floyd the Early Years 1966-1967 Cambridge St/Ation Pfrey1

PINK FLOYD THE EARLY YEARS 1966-1967 CAMBRIDGE ST/ATION PFREY1 <DVD + BLU-RAY> 1. 1966-1967 (Title) 2. ‘ Chapter 24’ Standard 8mm Film Rushes Syd Barrett Gog Magog Hills 1966 England Pink Floyd EMI Studios April 1967 London England 3. ‘Nick’s Boogie’ 16mm Film Rushes Recording Intersteller Overdrive & Nick’s Boogie Sound Techniques Studio January 11, 1967 Live at UFO, The Blarney Club January 13, 1967 London England 4. Interstellar Overdrive ‘Scene – Underground’ UFO The Blarney Club January 27, 1967 London England 5. Arnold Layne Promo Video Early 1967 Wittering Beach England 6. Pow R. Toc + Astronomy Domine + Hans Keller Interview With Syd Barrett & Roger Waters ‘The Look of the Week’ BBC Studios May 14, 1967 London England 7. The Scarecrow ‘Pathe Pictorial’ July 1967 England 8. Jugband Blues ‘London Line’ 1967 London England 9. Apples And Oranges + Interview with Dick Clark ‘American Bandstand’ November 7, 1967 Los Angeles USA 10. Instrumental Improvisation ‘Tomorrow’s World’ December 12, 1967 London England 11. Instrumental Improvisation ‘Die Jungen Nachtwandler’ UFO The Blarney Club February 24, 1967 London England 12. See Emily Play ‘Top Of The Pops’ BBC Studios July 6, 1967 London England 13. The Scarecrow ‘Out Takes’ July 1967 England 14. Interstellar Overdrive ‘Science Fiction – Das Universum Des Iches’ The Roundhouse 1967 London England PINK FLOYD THE EARLY YEARS 1968 GERMIN/ATION PFREY2 <DVD + BLU-RAY> 1. 1968 (Title) 2. Astronomy Domine 3. The Scarecrow 4. Corporal Clegg 5. Paint Box 6. Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun 7. See Emily Play 8. Bike ‘ Tienerklanken’ February18-19, 1968 Brussels Belgium 9. -

Time Pink Floyd Tab Pdf

Time pink floyd tab pdf Continue Pink Floyd achieved everything the band ever wanted - universal recognition, unthinkable sums of money and complete artistic freedom. But the follow-up to Dark Side was Wish You Were Here, an album that, as a decidedly sad record you can imagine, the story of a band that every dream came true just to understand the price they paid may have been too costly - the band's internal dynamics were broken (and never recovered), marriages were going south and Floyd once an attentive audience was replaced by fans screaming during quiet parts for Money. Songs like Have a Cigar and Welcome to the Machine are about how even giant bands feel cogs in, well, a machine. It really is one of the most depressing albums ever, because if these guys can't be happy after everything goes their way, can anyone be happy?! And if wish You Were Here is to be in Pink Floyd sucks, animals people suck. Breaking people into three Orwellian categories of pigs, dogs and sheep animals is a record I still can't get a handle. If you told me that you thought it was awful, I agree with you on some level - an album kind of simple, suffocating and oppressive thing that shouldn't work but does. The Cure could not match this nihilism on their most depressing day; Check out these texts from Dogs: You have to keep one eye looking over your shoulder / You know it's going to get harder and harder and harder as you get older / And eventually you'll get together and fly south / Hide your head in the sand / Just another sad old man / Just one and dying of cancer you won't always find interesting stories behind rock band names.