Motorola - Enforcement of Gprs Standard Essential Patents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saisie-Contrefaçon

Sabine Agé ÖV-Expertengespräch IP-Rechtsdurchsetzung in Europa Vienna ● 16 January 2017 Bringing evidence of infringement in France after the Enforcement directive: the saisie- contrefaçon and other available tools ÖV-Expertengespräch “IP-Rechtsdurchsetzung in Europa: Gut, besser … und morgen?” Vienna ● 16 January 2017 Sabine AGÉ Avocat Paris Lyon Evidence gathering in France after the IP Enforcement Dir. Overview Provisions of the IP Enforcement Directive (IPED) and of the French Intellectual Property Code (IPC) Overview of the means of evidence used in France Saisie-contrefaçon Protection of confidential information Use of the information gathered during the saisie- contrefaçon Right of information and rendering of accounts 2 Bringing evidence of infringement in France after the Enforcement directive: the saisie-contrefaçon and other available tools 1 Sabine Agé ÖV-Expertengespräch IP-Rechtsdurchsetzung in Europa Vienna ● 16 January 2017 Evidence gathering in France after the IP Enforcement Dir. IPED: a minimum Art. 2 : Scope “Without prejudice to the means which are or may be provided for in Community or national legislation, in so far as those means may be more favourable for rightholders, the measures, procedures and remedies provided for by this Directive shall apply, in accordance with Article 3, to any infringement of intellectual property rights as provided for by Community law and/or by the national law of the Member State concerned.” 3 Evidence gathering in France after the IP Enforcement Dir. IPED: fairness and proportionality Art. 3 : General obligation “1. Member States shall provide for the measures, procedures and remedies necessary to ensure the enforcement of the intellectual property rights covered by this Directive. -

Motorola SOW NICE-CISCO Integratin

WILLIAMSON COUNTY JUNE 11, 2018 NICE CISCO PHONE SYSTEM UPGRADE The design, technical, pricing, and other information (“Information”) furnished with this submission is proprietary and/or trade secret information of Motorola Solutions, Inc. (“Motorola Solutions”) and is submitted with the restriction that it is to be used for evaluation purposes only. To the fullest extent allowed by applicable law, the Information is not to be disclosed publicly or in any manner to anyone other than those required to evaluate the Information without the express written permission of Motorola Solutions. MOTOROLA, MOTO, MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS, and the Stylized M Logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Motorola Trademark Holdings, LLC and are used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. © 2018 Motorola Solutions, Inc. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Letter .......................................................................................................... Section 1 System Description ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 NICE CISCO Phone Integration Solution Overview ......................................................... 1-1 1.2 Phone Arbitration Solution Overview ............................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Responsiblities and Dependencies .................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 NRX Overview ................................................................................................................ -

THE DEFENSIVE PATENT PLAYBOOK James M

THE DEFENSIVE PATENT PLAYBOOK James M. Rice† Billionaire entrepreneur Naveen Jain wrote that “[s]uccess doesn’t necessarily come from breakthrough innovation but from flawless execution. A great strategy alone won’t win a game or a battle; the win comes from basic blocking and tackling.”1 Companies with innovative ideas must execute patent strategies effectively to navigate the current patent landscape. But in order to develop a defensive strategy, practitioners must appreciate the development of the defensive patent playbook. Article 1, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”2 Congress attempts to promote technological progress by granting patent rights to inventors. Under the utilitarian theory of patent law, patent rights create economic incentives for inventors by providing exclusivity in exchange for public disclosure of technology.3 The exclusive right to make, use, import, and sell a technology incentivizes innovation by enabling inventors to recoup the costs of development and secure profits in the market.4 Despite the conventional theory, in the 1980s and early 1990s, numerous technology companies viewed patents as unnecessary and chose not to file for patents.5 In 1990, Microsoft had seven utility patents.6 Cisco © 2015 James M. Rice. † J.D. Candidate, 2016, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. 1. Naveen Jain, 10 Secrets of Becoming a Successful Entrepreneur, INC. (Aug. 13, 2012), http://www.inc.com/naveen-jain/10-secrets-of-becoming-a-successful- entrepreneur.html. -

Review of the EU Copyright Framework

Review of the EU copyright framework European Implementation Assessment Review of the EU copyright framework: The implementation, application and effects of the "InfoSoc" Directive (2001/29/EC) and of its related instruments European Implementation Assessment Study In October 2014, the Committee on Legal Affairs (JURI) requested from the European Parliament Research Service (EPRS) an Ex Post Impact Assessment on Directive 2001/29/EC on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society (InfoSoc). This EPRS publication was originally commissioned in the context of JURI's own- initiative implementation report, which was adopted in Plenary in July 2015, Rapporteur Julia Reda MEP. However, it is also relevant to the work of JURI Committees' Working Group on Intellectual Property Rights and Copyright (CWG), chaired by Jean Marie Cavada MEP. Furthermore, this request was made in the wider context of the Commission's review of the EU legislative framework on copyright, and the ensuing legislative proposals, which have been a long time in the planning and which are now expected for the 4th quarter of 2015. The objective of these proposals is to modernise the EU copyright framework, and in particular the InfoSoc Directive, in light of the digital transformation. Accordingly, in response to the JURI request, the Ex-Post Impact Assessment Unit of the European Parliament Research Service decided to produce a "European Implementation Assessment on the review of the EU copyright framework". Implementation reports of EP committees are now routinely accompanied by European Implementation Assessments, drawn up by the Ex-Post Impact Assessment Unit of the Directorate for Impact Assessment and European Added Value, within the European Parliament's Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services. -

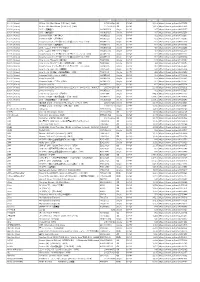

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Do the Anticompetitive Risks of Standards-Essential Patent Pools Outweigh Their Procompetitive Benefits?*

Glory Days: Do the Anticompetitive Risks of Standards-Essential Patent Pools Outweigh Their Procompetitive Benefits?* JOHN “JAY” JURATA, JR. & EMILY N. LUKEN1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION………………………………………...…………2 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................ 3 A. Patent Pools & Similar Arrangements...................................... 3 B. SEPs, FRAND, and Competition Law ....................................... 4 III. PATENT POOLS AND COMPETITION LAW ....................................... 6 A. Overview……………………………………………………………...6 B. Historical DOJ Business Review Letters on Patent Pools….….8 C. DOJ Avanci 5G Business Review Letter…………………………10 IV. SOME OF THE PROCOMPETITIVE ASSUMPTIONS FOR PATENT POOLS ARE NO LONGER ARE TRUE WHEN APPLIED TO FRAND- ENCUMBERED SEPS ..................................................................... 13 A. Market Power ......................................................................... 13 B. Reduced Transaction Costs ..................................................... 16 V. ANTICOMPETITIVE RISKS OF CERTAIN SEP POOLS ARE HIGHER TODAY COMPARED TO THE POOLS REVIEWED BY THE DOJ IN HISTORICAL BUSINESS REVIEW LETTERS .................................... 18 A. Licensing Agents Refusing to Comply with FRAND ............... 19 B. Structural Mechanisms Designed to Deter Adhering to FRAND Commitments ............................................................. 21 C. Including Non-SEPs to Collect Supra-FRAND Royalties ....... 25 D. Using Pools to Exploit -

Washington Apple Pi Journal, May 1988

Wa1hington Journal of WasGhington Appl e Pi, Ltd Volume. 10 may 1988 number 5 Hiahliaht.1 ' . ~ The Great Apple Lawsuit- (pgs4&so) • Timeout AppleWorks Enhancements - I IGs •Personal Newsletter & Publish It! ~ MacNovice: Word Processing- The Next Generati on ~ Views & Reviews: MidiPaint and Performer ~ Macintosh Virus: Technical Notes In This Issue. Officers & Staff, Editorial ................................ ...................... 3 Personal Newsletter and Publish It! .................... Ray Settle 40* President's Corner ........................................... Tom Warrick 4 • GameSIG News ....................................... Charles Don Hall 41 Event Queue, General Information, Classifieds ..................... 6 Plan for Use of Tutorial Tapes & Disks ................................ 41 AV-SIG News .............................................. Nancy Sefcrian 6 The Design Page for W.A.P .................................. Jay Rohr 42 Commercial Classifieds, Job Mart .......................................... 7 MacNovice Column: Word Processing .... Ralph J. Begleiter 47 * WAP Calendar, SIG News ..................................................... 8 Developer's View: The Great Apple Lawsuit.. ..... Bill Hole 50• WAP Hotline............................................................. ............. 9 Macintosh Bits & Bytes ............................... Lynn R. Trusal 52 Q & A ............................... Robert C. Platt & Bruce F. Field 10 Macinations 3 .................................................. Robb Wolov 56 Using -

Shifting Attitudes to Injunctions in Patent Cases

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| EUROPE PATENT INJUNCTIONS ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| Shifting attitudes to injunctions in patent cases Final injunctions for successful parties in patent cases in Europe have generally been seen as automatic. But, as Stephen Bennett , Stanislas Roux-Vaillard and Christian Mammen explain, attitudes are evolving ntil relatively recently, the question of whether a final injunction should be granted to a pat - MINUTE entee who has succeeded at trial has not really READ troubled the courts of Europe. Although the 1 Continental European civil law systems and the Despite their differing common law common law systems have approached the and civil law systems, courts in the Uissue from different starting points, the outcome has been over - UK and continental Europe have whelmingly the same: injunctions are granted to successful pat - tended to grant injunctions to suc - entees at the end of trial as a matter of course. cessful patent owners after a trial as Things are changing and the issue has been receiving a greater a matter of course. However, this po - degree of interest in recent times. This has arisen because of ar - sition has come under pressure guments made by defendants in (predominantly) cases con - thanks to arguments advanced by cerning patents for multi-function devices (mobile -

The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices

CRIDES Working Paper Series no. 2/2020 The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices by Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard February 2020 Cite as: Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard, The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices, CRIDES Working Paper Series no.2/2020 The CRIDES, Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire Droit Entreprise et Société, aims at investigating, on the one hand, the role of law in the enterprise and, on the other hand, the function of the enterprise within society. The centre, based at the Faculty of Law – UCLouvain, is formed by four research groups: the research group in economic law, the research group in intellectual property law, the research group in social law (Atelier SociAL), and the research group in tax law. www.uclouvain.be/fr/instituts-recherche/juri/crides This paper © Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard 2020 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ THE RISKS OF PATENT LITIGATION WITHIN THE EU ENFORCEMENT FRAMEWORK HOW TO ADDRESS ABUSIVE PRACTICES Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework The Risks of Patent Litigation Within the EU Enforcement Framework – How to Address Abusive Practices By Alain Strowel and Amandine Léonard* Keywords: Patent litigation, Flexibility and Injunctive Relief, Proportionality, Abuse of Rights, Patent Assertion Entities, Patent Trolls, Article 3(2) Enforcement Directive, Directive (EU) 2004/48 Abstract The debate over the degree of flexibility at the disposal of national courts in Europe to grant, deny, or tailor, injunctive relief in patent litigation seems to be a never-ending story. -

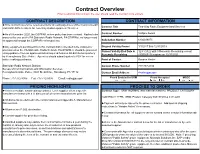

Contract Overview Prior to Utilizing This Contract, the User Should Read the Contract in Its Entirety

Contract Overview Prior to utilizing this contract, the user should read the contract in its entirety. CONTRACT DESCRIPTION CONTRACT INFORMATION ►This contract covers the requirements for all using Agencies of the Commonwealth Two-Way Radio Equipment and Services and COSTARS members for Two-Way Radio Equipment/ Services. Contract Title ►As of November 2020, the COPPAR review policy has been revised. Radios to be Contract Number Multiple Award procured for use on the PA Statewide Radio Network, PA-STARNet, no longer must be approved through the COPPAR review process. Solicitation Number 6100039075 ►Any equipment purchased from this contract that is intended to be installed or Original Validity Period 1/1/2017 thru 12/31/2019 provisioned on the PA Statewide Radio Network, PA-STARNet, should be procured Current Validity End Date & 12/31/2022 with 0 Renewals Remaining except using guidance from an approved radios/required features list distributed quarterly Renewals Remaining 4400020114 expires on 12/31/2021 by Pennsylvania State Police. Agencies should submit quotes to PSP for review before making purchases. Point of Contact Raeden Hosler Statewide Radio Network Division Contact Phone Number 717-787-4103 Bureau of Communications and Information Services Pennsylvania State Police, 8001 Bretz Drive, Harrisburg, PA 17112 Contact Email Address [email protected] Phone: 717-772-8005 Fax: 717-772-8097 Email: [email protected] Pcard Enabled in SRM Pcard Accepted MSCC Yes No Yes No Yes No PRICING HIGHLIGHTS PROCESS TO ORDER ►This is a multiple award catalog contract. Each supplier offers a specific Contract Type: SRM: NORMAL (has material masters), PRODUCT CATEGORY manufacturer brand with a % discount off of current manufacturer price list. -

Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights

ENFORCEMENT OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS Report on the application of Directive 2004/48 BEUC Response Contact: Kostas Rossoglou – [email protected] Ref.: X/2011/041 - 31/03/11 BEUC, the European Consumers’ Organisation 80 rue d’Arlon, 1040 Bruxelles - +32 2 743 15 90 - www.beuc.eu EC register for interest representatives: identification number 9505781573-45 Summary The European Consumers’ Organisation (BEUC) welcomes the opportunity to submit its views on the implementation of the IPR Enforcement Directive 2004/48 and its ongoing review. BEUC is concerned with the approach followed by the European Commission (DG Markt) vis-à-vis Intellectual Property Rights and the proposals outlined in the report regarding the need to revise the current rules. BEUC is strongly opposed to a possible revision that would aim at eroding consumers’ fundamental rights and at establishing disproportionate enforcement mechanisms for a number of reasons. In particular: • The Directive has been implemented by Member States only recently and therefore the feedback on its effectiveness remains limited; • The European Commission has yet to carry out the assessment of the impact of the Directive on innovation and the development of the information society, as required by Article 18 of the Directive 2004/48; • The decision to revise the Directive has been based on the feedback received by right holders’ representatives within the framework of a stakeholder dialogue established by DG Markt without the participation of civil society, academics and data protection authorities; -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954