The Six Purposes of Drill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nscc/Nlcc Uniform Regulations

U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps Manual NSCC/NLCC UNIFORM REGULATIONS NSCPUB 500 OCTOBER 2011 National Headquarters – 2300 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 200, Arlington, Virginia 22201-5424 Copyright © 2011 Naval Sea Cadet Corps 36 USC 154106 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK RECORD OF CHANGES CHANGE NUMBER TITLE OR REFERENCE OF CHANGE DATE INCORPORATED 1 NSCC ACTION LETTER 04-12 12 APR 12 2 NSCC ACTION LETTER 03-13 22 MAR 13 3 NSCC ACTION LETTER 09-13 25 OCT 13 4 NSCC ACTION LETTER 01-14 06 FEB 14 5 NSCC ACTION LETTER 05-14 04 AUG 14 6 NSCC ACTION LETTER 08-14 17 OCT 14 7 NSCC ACTION LETTER 11-14 15 DEC 14 8 NSCC ACTION LETTER 02-15 26 FEB 15 THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE GENERAL UNIFORM REGULATIONS SECTION 1: GENERAL INFORMATION SECTION 1. POLICY................................................................1101 2. HISTORY...............................................................1102 3. ENFORCEMENT...........................................................1103 4. HEADGEAR..............................................................1104 5. ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS.............................................1105 6. CLOTHING ALLOWANCES AND DEPOSITS......................................1106 SECTION 2: AUTHORITY TO PRESCRIBE 1. GENERAL...............................................................1201 2. PRESCRIBING AUTHORITY.................................................1202 3. CHAIN OF COMMAND......................................................1203 4. PRESCRIBED UNIFORMS...................................................1204 -

MEDINA PARKING GARAGE 132 N. Elmwood Ave., Medina, OH 44256 DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION TEAM SPECIFICATIONS

MEDINA PARKING GARAGE 132 N. Elmwood Ave., Medina, OH 44256 SPECIFICATIONS DESIGN/CONSTRUCTION TEAM Mike Coates Construction Co. Inc. Rich & Associates, Inc. General Contractor Parking Consultants 800 Summit Ave. 26877 Northwestern Hwy. Suite 208 Niles, OH 44446 Southfield, MI 48033 (330) 652-0190 (248) 353-5080 BSHM Architects, Inc. Karpinski Engineering Historical Consultant Mechanical, Plumbing, Electrical, Technology 15 Central Square, Ste. 300 13714 Cleveland Ave., NW Youngstown, OH 44503 Uniontown, OH 44685 (330) 744-0770 (330) 699-4077 Medina Parking Structure Division 03 - Concrete 03 38 16 - Unbonded Post - Tensioned Concrete 03 30 00 - Cast - In - Place Concrete Division 04 - Unit Masonry 04 20 00 - Unit Masonry Division 05 - Structural Steel 05 12 00 - Structural Steel 05 15 16 - Steel Wire Rope Railing Assembly 05 21 00 - Steel Joist Framing 05 31 00 - Steel Decking 05 50 00 - Metal Fabricating 05 52 00 - Metal Railings Division 07 - Traffic Coatings 07 18 00 - Traffic Coatings 07 19 00 - Water Repellents Division 20 - Fire Protection, Plumbing & HVAC General Provisions 20 01 00 - Fire Protection, Plumbing & HVAC General Provisions 21 03 00 - Fire Protection Basic Materials and Methods 21 10 00 - Water Based Fire Protection Systems 22 03 00 - Plumbing Basic Material and Methods 22 07 00 - Plumbing Insulation 22 10 00 - Plumbing System Components Division 23 - Split System Air Conditioners 23 81 26 - Split System Air Conditioners 23 82 03 - Electric Heating Units Division 26 - Electrical General Provisions 26 01 00 - Electrical -

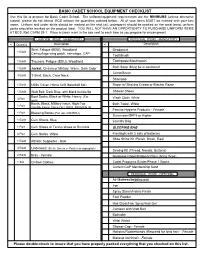

BASIC CADET SCHOOL EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST Use This List to Prepare for Basic Cadet School

BASIC CADET SCHOOL EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST Use this list to prepare for Basic Cadet School. The uniform/equipment requirements are the MINIMUMS (unless otherwise stated), please do not attend BCS without the quantities outlined below. All of your items MUST be marked with your last name. Uniform and under shirts should be marked on the shirt tail, underpants should be marked on the waist band, uniform pants should be marked on the product label. YOU WILL NOT HAVE AN OPPORTUNITY TO PURCHASE UNIFORM ITEMS AT BCS. Ref: CAPM 39-1. Place a check mark in the box next to each item as you prepare for encampment. UNIFORM ITEMS - MANDATORY PERSONAL ITEMS - MANDATORY ✔ Quantity Description ✔ Description Shirt, Fatigue (BDU), Woodland Deodorant 1 Each Camouflage wing patch, nametape, CAP Toothbrush 1 Each Trousers, Fatigue (BDU), Woodland Toothpaste/Mouthwash 1 Each Jacket, Civilian or Military, Warm, Dark Color Bath Soap (Must be in container) Comb/Brush 3 Each T-Shirt, Black, Crew Neck Shampoo 1 Each Utility Cover, Home Unit (baseball hat) Razor w/ Shaving Cream or Electric Razor 1 Each Web Belt, Dark Blue, with black buckle/tip Shower Shoes Boot Socks, Black or White, Heavy (For 3 Pair Wash Cloth, White wear Boots, Black, Military Issue, High-Top Bath Towel, White 1 Pair Grn/Blk Fabric Sides-OK / WELL BROKEN IN Femine Hygiene Products - Female 1 Pair Blousing Bands (For use with BDU) Sunscreen/SPF8 or Higher 1 Each Gym Shorts, Blue Laundry Bag 1 Pair Gym Shoes or Tennis shoes or Running SLEEPING BAG 4 Pair Gym Socks, White Flashlight with 2 sets of -

Cahill Aides Offer Coverup Charge Rebuttal Evidence TRENTON (AP) - Cahill Taining to the Investigations

The Weather THEDAILY FINAL Cloudy, cool with periods of > Red Bank, Freehold T~ rain today, tonight and tomr- I Long Branch / row. Temperatures mostly in EDITION 50s. 3R PAf.ES- Monmouth County's Outstanding Home Newspaper Plus Tabloid VOL.95 NO.209 RED BA1NK, NJ. THURSDAY, APRIL 26,1973 TEN CENTS iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiHiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiinnnnifa Cahill Aides Offer Coverup Charge Rebuttal Evidence TRENTON (AP) - Cahill taining to the investigations. torneys General Peter R. The back of the check tive James J. Challender was administration officials have An Associated Press report- Richards and Edwin H. Stier. showed it was cashed at Gar- assigned June 19, 1972, to in- shown documents to reporters er was allowed to see the Capt. William Baum, head of den State Park racetrack, vestigate the extent to which to rebut charges they covered documents yesterday at his the State Police intelligence which is owned by Eugene other campaign checks might up an investigation into Re- own request by State Criminal bureau, was also present. Mori, father-in-law of former have been cashed at Garden publican fundraising during •Justice Director Evan W. The campaign fundraising State Treasurer Joseph M. State. the 1969 gubernatorial cam- Jahos. Two other reporters investigations began, state au- •McCrane. On the front of the paign. Kugler has since said cash- have been allowed to see the thorities said, in the spring of check was written in longhand ing checks at a race track is The documents viewed yes- documents. 1972 when Baum received notation, "Bill Cahill Cam- not illegal. terday were intended to show Attorney General George F. -

Vanderbilt University Nrotc Midshipmen Regulations

VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY NROTC MIDSHIPMEN REGULATIONS VUNROTCINST 5400A 22 Jul 19 VUNROTCINST 5400A 22 Jul 19 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Purpose & Mission................................................................3 Chapter II: The NROTC Program...........................................................4 Chapter III: Naval Professional and General Academic Requirements...7 Chapter IV: Academic Standards............................................................9 Chapter V: Organization of Vanderbilt NROTC..................................12 Chapter VI: The Battalion......................................................................15 Chapter VII: Naval Professional Training..............................................18 Chapter VIII: Midshipman Pay, Benefits, and Allowances.....................20 Chapter IX: Conduct and Discipline......................................................23 Chapter X: Uniforms and Appearance..................................................25 Chapter XI: Physical Fitness..................................................................60 Chapter XII: Evaluations.........................................................................62 Chapter XIII: Midshipman Awards..........................................................63 Appendix I: Standards of Conduct.........................................................65 Appendix II: NROTC Specified Required Courses................................69 Appendix III: Required Naval Science Courses......................................70 Appendix IV: Battalion -

Jefferson Street/N. 8Th Avenue

Brown County Parks Reforestation Camp Campground Construction Brown County Parks Village of Suamico Brown County, Wisconsin February 2021 Prepared by: BAUDHUIN SURVEYING & ENGINEERING 312 North 5th Avenue P.O. Box 105 Sturgeon Bay, WI 54235 Phone (920) 743-8211 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIDDING REQUIREMENTS Bid Form and Proposal SPECIFICATIONS Division 02- 02 41 13 Demolition Existing Conditions Division 03- Concrete 03 10 00 Concrete Formwork 03 20 00 Concrete Reinforcement 03 30 00 Cast In-Place Concrete Division 22- Plumbing 22 05 14 Plumbing Specialties Division 26- Electrical 26 05 00 Common Work Results for Electrical 26 05 04 Cleaning, Inspection and Testing of Electrical Equipment 26 05 19 Low-Voltage Electrical Power and Cables 26 05 26 Grounding and Bonding for Electrical Systems 26 24 16 Panelboards 26 24 18 Electrical Pedestals for Campsites Division 31- Earthwork 31 10 00 Site Clearing 31 20 00 Earthmoving 31 22 16.15 Roadway Subgrade Preparation 31 23 16.13 Trenching 31 23 16.16 Structural Excavation for Minor Structures 31 23 19 Dewatering 31 25 00 Erosion Control Division 32- Exterior Improvements 32 11 23.33 Dense Graded Base 32 91 13 Soil Preparation 32 91 13.50 Stormwater Detention 32 92 19 Seeding Division 33- Utilities 33 11 00 Water Utility Distribution Piping 33 30 00 Sanitary Sewerage Utilities SPECIAL PROVISIONS Bathhouse Details Septic Tank Details Grinder Pump Specifications 40347005.doc BID FORM AND PROPOSAL Quantity Item # Description Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Total Units Unit Price Phase 1 Price Phase 2 Price Phase -

Lèxic Uniformològic Multilingüe

FERRAN LUPESCU LÈXIC UNIFORMOLÒGIC MULTILINGÜE CATALÀ-ENGLISH-ESPAÑOL-FRANÇAIS-ITALIANO-PORTUGUÊS AMB SUPLEMENTS ALEMANY, ROMANÈS I RUS SOCIETAT D’ESTUDIS MILITARS 2017 1 2 En homenatge al mestre Preben Kannik (1914-1967) (c) Ferran Lupescu, 2017 3 4 Sumari Introducció 7 Esquema de les entrades 9 1. Uniformologia general 11 2. Cascos 23 3. Lligadures (altres que cascos) 27 4. Peces superiors 47 5. Peces superiors: peces d’abrigar i antiintempèrie 59 6. Peces inferiors 63 7. Peces de cos sencer 69 8. Roba interior 71 9. Calçat i elements afins 73 10. Insígnies i ornaments 77 11. Equipament 83 Annex A: armes individuals 95 Annex B: estructura bàsica de les Forces Armades 101 Annex C: tipologia bàsica de militars segons branques i especialitats 107 Annex D: tipologia bàsica de militars segons categoria i graduació 113 Suplement I: petit glossari alemany 117 Suplement II: petit glossari romanès 129 Suplement III: petit glossari rus 137 5 6 INTRODUCCIÓ Tota llengua que aspira a la plena normalitat d'ús ha de tenir coberta la terminologia especialitzada de tots els camps de coneixement. Emperò, el català, avui per avui, a còpia de desús i desinterès, és deficitari en força camps de la terminologia militar, i, particularment, en el de la uniformologia. S’hi acumulen manta mancances greus, entre les quals la imprecisió (“gorra” per ‘casquet’, “jaqueta” per ‘guerrera’), el confusionisme (“xarretera” per ‘musclera’, “distintiu” per 'divisa' i per 'emblema') i els barbarismes innecessaris (en espanyol, francès o anglès); precarietats impròpies d'una llengua madura que, de fet, campen ufanoses per reglaments uniformològics de cossos policials catalans, per exemple. -

United States Marine Corps Cco 1020.11V

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS MARINE AIR GROUND TASK FORCE TRAINING COMMAND MARINE CORPS AIR GROUND COMBAT CENTER BOX 788100 TWENTYNINE PALMS, CALIFORNIA 92278-8100 CCO 1020.11V CG 17 Jul 18 COMBAT CENTER ORDER 1020.11V From: Commanding General To: Distribution List Subj: COMBAT CENTER UNIFORM AND CIVILIAN ATTIRE REGULATIONS FOR ARMED FORCES PERSONNEL Ref: (a) MCO P1020.34 (b) U.S. Navy Uniform Regulations, NavPers 15665I (NOTAL) (c) MCO 5100.19F (d) CCO 1630.8F (e) MARADMIN 078/14 (f) ALMAR 035/07 (g) ALMAR 038/16 (h) ALMAR 019/08 (i) MARADMIN 695/11 (j) MARADMIN 011/16 (k) MCO 5512.11D (l) Marine Corps Manual (m) CCO 12990.1 1. Situation. The purpose of this Order is to establish specific local regulations for the wearing of uniforms on and off the Combat Center for Military Personnel. The references apply. a. Reference (a) sets forth the current policies regarding uniform and grooming regulations for the Marine Corps and assigned Navy personnel. b. Reference (b) sets forth uniform regulations for Navy personnel. The uniform of the day and authorized alternate uniforms are prescribed by the Naval Area Coordinator, Commander Naval Base, San Diego, as modified by this Order. c. References (c) and (d) set forth current policies regarding traffic safety (to include pedestrian and bicycle safety) for the Marine Corps and assigned Navy personnel. d. References (e) and (f) provide direction on the wearing of the Marine Corps Combat Utility Uniform (MCCUU) [also contained in reference (a)]. e. Reference (g) provides direction on the seasonal uniform change [also contained in reference (a)]. -

What Is the Best Way to Begin Learning About Fashion, Trends, and Fashion Designers?

★ What is the best way to begin learning about fashion, trends, and fashion designers? Edit I know a bit, but not much. What are some ways to educate myself when it comes to fashion? Edit Comment • Share (1) • Options Follow Question Promote Question Related Questions • Fashion and Style : Apart from attending formal classes, what are some of the ways for someone interested in fashion designing to learn it as ... (continue) • Fashion and Style : How did the fashion trend of wearing white shoes/sneakers begin? • What's the best way of learning about the business behind the fashion industry? • Fashion and Style : What are the best ways for a new fashion designer to attract customers? • What are good ways to learn more about the fashion industry? More Related Questions Share Question Twitter Facebook LinkedIn Question Stats • Latest activity 11 Mar • This question has 1 monitor with 351833 topic followers. 4627 people have viewed this question. • 39 people are following this question. • 11 Answers Ask to Answer Yolanda Paez Charneco Add Bio • Make Anonymous Add your answer, or answer later. Kathryn Finney, "Oprah of the Internet" . One of the ... (more) 4 votes by Francisco Ceruti, Marie Stein, Unsah Malik, and Natasha Kazachenko Actually celebrities are usually the sign that a trend is nearing it's end and by the time most trends hit magazine like Vogue, they're on the way out. The best way to discover and follow fashion trends is to do one of three things: 1. Order a Subscription to Women's Wear Daily. This is the industry trade paper and has a lot of details on what's happen in fashion from both a trend and business level. -

De Blasio Dilemma on No Fatalities on ‘Boulevard of Death’ Last Year for fi Rst Time Since 1990 Homeless Vets by BILL PARRY

• JAMAICA TIMES • ASTORIA TIMES • FOREST HILLS LEDGER • LAURELTON TIMES LARGEST AUDITED • QUEENS VILLAGE TIMES COMMUNITY • RIDGEWOOD LEDGER NEWSPAPER • HOWARD BEACH TIMES IN QUEENS • RICHMOND HILL TIMES Jan. 22–28, 2016 Your Neighborhood — Your News® FREE ALSO COVERING ELMHURST, JACKSON HEIGHTS, LONG ISLAND CITY, MASPETH, MIDDLE VILLAGE, REGO PARK, SUNNYSIDE Hollis faces Vision Zero works: de Blasio dilemma on No fatalities on ‘Boulevard of Death’ last year for fi rst time since 1990 homeless vets BY BILL PARRY BY SADEF ALI KULLY FINISHING TOUCHES For the first time in a quar- ter of a century there were no A few homeless veterans fatalities on the Boulevard of were scheduled to move this Death in 2015. Thursday into the much dis- No wonder Mayor Bill de puted affordable housing units Blasio came to Queens Bou- owned by Queens landlord levard Tuesday to announce Rita Stark in Hollis despite his Vision Zero initiative is pushback from community working so well that 2015 was members, according to the the safest year on city streets city’s Human Resources Ad- since record-keeping began ministration in 1910, with traffic fatalities While the city and state down 22 percent and 66 fewer administrations gather forces lives lost since 2013. to end homelessness, dozens The mayor pledged to go of Hollis community mem- even further in 2016 by unveil- bers are putting on the gloves ing $115 million in new capital to stop government agencies investment for plans to calm from bringing homeless vet- traffic as well as expand ef- erans into affordable housing forts to crack down on danger- units in their neighborhood. -

Uniform Regulation Order

• UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS MARINE CORPS INSTALLATIONS NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION • MARINE CORPS BASE QUANTICO QUANTICO VIRGINIA 22134 5001 MCINCR-MCBQO 1020.1K B 10 3 May 21 MARINE CORPS INSTALLATIONS NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION-MARINE CORPS BASE QUANTICO ORDER 1020.1K From: Commander To: Distribution List Subj: UNIFORM REGULATIONS Ref: (a) MCO P1020.34H (b) MCBO 3570.1A Cc) CMC ltrlO2O MCUB dtd 14 Aug 07 Cd) ALMAR 035/07 Ce) ALMAR 028/19 (f) MCBO 5560.2E (g) MCO 5100.19F (h) MARADMIN 078/14 (1) MARADMIN 011/16 End: (1) Marine Corps Base Quantico (MCDQ) Physical Training (PT) Attire 1. Situation. To promulgate instructions per references (a) through (i) for the proper wearing of the military uniform and civilian clothing by Service members and civilian personnel aboard MCINCR-MCBQ. 2. Cancellation. MCBO 1020.1J 3. Mission. Commanding Officers, directors, heads of tenant activities will ensure compliance with the references and this Order for the wear of uniforms and civilian attire. 4. Execution a. Commander’s Intent and Concept of Operations (1) Commander’s Intent. To ensure all personnel are aware of the proper wear of uniform and civilian clothing while assigned to and aboard MCINCR-MCBQ. (2) Concept of Operations (a) Ensure all personnel possess the full requirement of prescribed articles of uniform clothing and maintain such uniforms together with uniform accoutrements in a neat and serviceable condition. (b) Ensure personnel of other services, attached to this activity, wear uniforms corresponding to the requirements of this Order on all occasions. b. Coordinating Instructions DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. -

2021 Water, Sewer, Pavement Improvements Project

PROJECT SPECIFICATIONS for 2021 WATER, SEWER, PAVEMENT IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT CITY OF DEL MAR CALIFORNIA May 27, 2021 PROJECT SPECIFICATIONS for 2021 WATER, SEWER, PAVEMENT IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT CITY OF DEL MAR CALIFORNIA Prepared by: City of Del Mar 1050 Camino Del Mar Del Mar, CA 92014 Approved By: May 27, 2021 a Joe Bride, R.C.E 52107 DATE Public Works Director 2021 WATER, SEWER, PAVEMENT IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS BIDDING INFORMATION AND BID DOCUMENTS Notice Inviting Bids ...................................................................................................................................... BI-1 Information and Instructions for Bidders ..................................................................................... BI-2 thru BI-5 Proposal to the City of Del Mar for 2021 Water, Sewer, Pavement Improvements ................................... BI-6 Proposal – Bid Schedule ............................................................................................................... BI-7 thru BI-9 Proposal – Designation of Subcontractors ............................................................................................. …BI-10 Proposal – General Information Required of Bidder ................................................................................ .BI-11 Proposal – Equipment/Material Source Information ................................................................................. BI-12 Proposal – Public Contract Code Section 10162 Questionnaire ...............................................................