Art and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

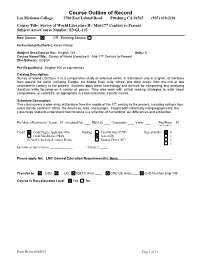

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Patrick J. Hurley's Attempt to Unify China, 1944-1945

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-11 791 SMITH, Robert Thomas, 1938- ALONE IN CHINA; PATRICK J. HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1966 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan C opyright by ROBERT THOMAS SMITH 1966 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHCMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALONE IN CHINA: PATRICK J . HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ROBERT THCÎ-1AS SMITH Norman, Oklahoma 1966 ALŒE IN CHINA; PATRICK J . HURLEY'S ATTEMPT TO UNIFY CHINA, 1944-1945 APPP>Î BY 'c- l <• ,L? T\ . , A. c^-Ja ^v^ c c \ (LjJ LSSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENT 1 wish to acknowledge the aid and assistance given by my major professor, Dr, Gilbert 0, Fite, Research Professor of History, I desire also to thank Professor Donald J, Berthrong who acted as co-director of my dissertation before circumstances made it impossible for him to continue in that capacity. To Professors Percy W, Buchanan, J, Carroll Moody, John W, Wood, and Russell D, Buhite, \^o read the manuscript and vdio each offered learned and constructive criticism , I shall always be grateful, 1 must also thank the staff of the Manuscripts Divi sion of the Bizzell Library \diose expert assistance greatly simplified the task of finding my way through the Patrick J, Hurley collection. Special thanks are due my wife vdio volun teered to type the manuscript and offered aid in all ways imaginable, and to my parents \dio must have wondered if I would ever find a job. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Sometimes You Have to Break the Rules Sunday, August 22, 2021, 11:15 A.M., All Saints Church, Pasadena the Rev

1 Sometimes You Have to Break the Rules Sunday, August 22, 2021, 11:15 a.m., All Saints Church, Pasadena The Rev. Mike Kinman The scholar asked Jesus, “Which commandment is the first of all?” + If you could be at any concert or performance in your lifetime, what would you choose? The Beatles at Shea Stadium? Pink Floyd doing The Wall at the Berlin Wall? Coachella with Beyonce in 2018 The Monterrey Pop Festival with Janis Joplin Woodstock Would it be the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival that’s featured in Summer of Soul - Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly & the Family Stone, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, The 5th Dimension .. Clara Williams. That would be pretty awesome. But no, for me, I know my answer. For me, it would be July 13, 1985 – Wembley Stadium. Live Aid. 1.9 billion people – 40 percent of the world’s population watching. $127 million raised for famine relief in Ethiopia. And the lineup … a little light on women but still incredible … David Bowie, Elvis Costello, Sting, Elton John, The Who, Paul McCartney, Freddie Mercury and Queen leading all 72,000 people in singing Radio Gaga. 72,000 people clapping their hands over their head in unison. What it would have been like to be there. But for me … I would want to have been there for one moment. Live Aid was a lot of things, but one of them was it was the global coming out party for an Irish band called U2. Maybe you’ve heard of them. And I’d want to be there to witness one moment. -

![David Bowie a New Career in a New Town [1977-1982] Mp3, Flac, Wma](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4828/david-bowie-a-new-career-in-a-new-town-1977-1982-mp3-flac-wma-274828.webp)

David Bowie a New Career in a New Town [1977-1982] Mp3, Flac, Wma

David Bowie A New Career In A New Town [1977-1982] mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: A New Career In A New Town [1977-1982] Country: UK, Europe & US Released: 2017 Style: Avantgarde, Art Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1738 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1509 mb WMA version RAR size: 1377 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 572 Other Formats: AIFF AAC MP1 XM VOC MOD VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Low A1 Speed Of Life A2 Breaking Glass What In The World A3 Vocals – Iggy Pop A4 Sound And Vision A5 Always Crashing In The Same Car A6 Be My Wife A7 A New Career In A New Town B1 Warszawa B2 Art Decade B3 Weeping Wall B4 Subterraneans Heroes C1 Beauty And The Beast C2 Joe The Lion C3 “Heroes” C4 Sons Of The Silent Age C5 Blackout D1 V-2 Schneider D2 Sense Of Doubt D3 Moss Garden D4 Neuköln D5 The Secret Life Of Arabia "Heroes" EP E1 “Heroes” / ”Helden” (German Album Version) E2 “Helden” (German Single Version) F1 “Heroes” / ”Héros” (French Album Version) F2 “Héros” (French Single Version) Stage (Original) G1 Hang On To Yourself G2 Ziggy Stardust G3 Five Years G4 Soul Love G5 Star H1 Station To Station H2 Fame H3 TVC 15 I1 Warszawa I2 Speed Of Life I3 Art Decade I4 Sense Of Doubt I5 Breaking Glass J1 “Heroes” J2 What In The World J3 Blackout J4 Beauty And The Beast Stage K1 Warszawa K2 “Heroes” K3 What In The World L1 Be My Wife L2 The Jean Genie L3 Blackout L4 Sense Of Doubt M1 Speed Of Life M2 Breaking Glass M3 Beauty And The Beast M4 Fame N1 Five Years N2 Soul Love N3 Star N4 Hang On To Yourself N5 Ziggy Stardust N6 Suffragette City O1 Art Decade O2 Alabama Song O3 Station To Station P1 Stay P2 TVC 15 Lodger Q1 Fantastic Voyage Q2 African Night Flight Q3 Move On Q4 Yassassin (Turkish For: Long Live) Q5 Red Sails R1 D.J. -

What in the World 2020

Level 1 (Grades 5 and up) Th eWE Controversy Black Lives Matter Pandemic Update Th e Search for a COVID Vaccine 2020/2021: Issue 1 A monthly current events resource for Canadian classrooms Routing Slip: (please circulate) What in the World What in the World? Level 1, 2020/2021: Issue 1 Mission Statement PUBLISHER LesPlan Educational Services Ltd. aims to help teachers develop Eric Wieczorek students’ engagement in, understanding of, and ability to EDITOR-IN-CHIEF critically assess current issues and events by providing quality, Janet Radschun Wieczorek up-to-date, aff ordable, ready-to-use resources appropriate for ILLUSTRATOR use across the curriculum. Mike Deas CONTRIBUTORS Vivien Bowers Krista Clarke Denise Hadley Rosa Harris Jacinthe Lauzier Alexia Malo Catriona Misfeldt David Smart What in the World? © is published eight times during the school year by: LesPlan Educational Services Ltd. #1 - 4144 Wilkinson Road Victoria BC V8Z 5A7 www.lesplan.com [email protected] Phone: (toll free) 888 240-2212 Fax: (toll free) 888 240-2246 Twitter: @LesPlan Subscribe to What in the World? © at a cost of $24.75 per month, per school. Copyright and Licence I have had many parents comment to me Th ese materials are protected by copyright. about how great they think What in the Subscribers may copy each issue for use by World? is, and they look forward to each all students and teachers within one school. Subscribers must also ensure that the materials are month’s issue coming home...Th is is a great not made available to anyone outside their school. resource for a small country school to Complimentary sample explore the global issues that aff ect us all. -

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto

GOTHIC FICTION Introduction by Peter Otto 1 The Sadleir-Black Collection 2 2 The Microfilm Collection 7 3 Gothic Origins 11 4 Gothic Revolutions 15 5 The Northanger Novels 20 6 Radcliffe and her Imitators 23 7 Lewis and her Followers 27 8 Terror and Horror Gothic 31 9 Gothic Echoes / Gothic Labyrinths 33 © Peter Otto and Adam Matthew Publications Ltd. Published in Gothic Fiction: A Guide, by Peter Otto, Marie Mulvey-Roberts and Alison Milbank, Marlborough, Wilt.: Adam Matthew Publications, 2003, pp. 11-57. Available from http://www.ampltd.co.uk/digital_guides/gothic_fiction/Contents.aspx Deposited to the University of Melbourne ePrints Repository with permission of Adam Matthew Publications - http://eprints.unimelb.edu.au All rights reserved. Unauthorised Reproduction Prohibited. 1. The Sadleir-Black Collection It was not long before the lust for Gothic Romance took complete possession of me. Some instinct – for which I can only be thankful – told me not to stray into 'Sensibility', 'Pastoral', or 'Epistolary' novels of the period 1770-1820, but to stick to Gothic Novels and Tales of Terror. Michael Sadleir, XIX Century Fiction It seems appropriate that the Sadleir-Black collection of Gothic fictions, a genre peppered with illicit passions, should be described by its progenitor as the fruit of lust. Michael Sadleir (1888-1957), the person who cultivated this passion, was a noted bibliographer, book collector, publisher and creative writer. Educated at Rugby and Balliol College, Oxford, Sadleir joined the office of the publishers Constable and Company in 1912, becoming Director in 1920. He published seven reasonably successful novels; important biographical studies of Trollope, Edward and Rosina Bulwer, and Lady Blessington; and a number of ground-breaking bibliographical works, most significantly Excursions in Victorian Bibliography (1922) and XIX Century Fiction (1951). -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five .............................................................................................