Murder and Madness in a Mennonite Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinawa Provincial Park Management Plan 2 | Pinawa Provincial Park

Pinawa Provincial Park Management Plan 2 | Pinawa Provincial Park Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................. 3 2. Park History .................................. 3 3. Park Attributes ............................. 4 3.1 Natural .......................................................... 4 3.2 Recreational .................................................. 4 4. Park Management Framework ..... 6 4.1 Park Classification ........................................ 6 4.2 Park Purpose ................................................ 6 4.3 Land Use Categories ..................................... 6 5. Park Management Guidelines ....... 6 5.1 Natural Values ............................................... 6 5.2 Recreation ..................................................... 6 Appendix .......................................... 7 A. Park Classification and Land Use Categories Bibliography ..................................... 8 This management plan for Pinawa Provincial Park was prepared in consultation with park users under the authority of The Provincial Parks Act. Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship Parks and Natural Areas Branch December 2012 Management Plan | 3 The process of preparing this management plan and co-ordinating the public involvement process was the responsibility of a team involving staff from Parks and Natural Areas branch, regional staff of Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship and a consultant contracted to work on the project. Preparation of the management plan involved a number of steps. -

Rural Municipality of Rossburn Information Bulletin 98-3 Page 1

Rural Municipality of Rossburn Information Bulletin 98-3 Rural Municipality of Rossburn Information Bulletin 98-3 Page 1 Rural Municipality of Rossburn Information Bulletin 98-3 Prepared by: Land Resource Unit, Brandon Research Centre, Research Branch, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Department of Soil Science, University of Manitoba. Manitoba Soil Resource Section, Soils and Crops Branch, Manitoba Agriculture. Printed December, 1998 Page 2 Information Bulletin 98-3 Rural Municipality of Rossburn PREFACE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is one of a new series of information bulletins for individual Continuing support for this project has been provided by Brandon rural municipalities of Manitoba. They serve to introduce the newly Research Centre and PFRA Manitoba. The project was initiated by developed digital soil databases and illustrate several typical derived the Land Resource Unit under the Canada-Manitoba Agreement of and interpretive map products for agricultural land use planning Agricultural Sustainability. applications. The bulletins will also be available in diskette format for each rural municipality. The following individuals and agencies contributed significantly to the compilation, interpretation, and derivation of the information Information contained in this bulletin may be quoted and utilized contained in this report. with appropriate reference to the originating agencies. The authors and originating agencies assume no responsibility for the misuse, Managerial and administrative support was provided by: alteration, re-packaging, or re-interpretation of the information. R.G. Eilers, Head, Land Resource Unit, Brandon Research Centre, This information bulletin serves as an introduction to the land Research Branch, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. resource information available for the municipality. More detailed G.J. -

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the Period 2002 to 2012

Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area Definitions for the period 2002 to 2012 The following list identifies the RHAs and RHA Districts in Manitoba between the period 2002 and 2012. The 11 RHAs are listed using major headings with numbers and include the MCHP - Manitoba Health codes that identify them. RHA Districts are listed under the RHA heading and include the Municipal codes that identify them. Changes / modifications to these definitions and the use of postal codes in definitions are noted where relevant. 1. CENTRAL (A - 40) Note: In the fall of 2002, Central changed their districts, going from 8 to 9 districts. The changes are noted below, beside the appropriate district area. Seven Regions (A1S) (* 2002 changed code from A8 to A1S *) '063' - Lakeview RM '166' - Westbourne RM '167' - Gladstone Town '206' - Alonsa RM 'A18' - Sandy Bay FN Cartier/SFX (A1C) (* 2002 changed name from MacDonald/Cartier, and code from A4 to A1C *) '021' - Cartier RM '321' - Headingley RM '127' - St. Francois Xavier RM Portage (A1P) (* 2002 changed code from A7 to A1P *) '090' - Macgregor Village '089' - North Norfolk RM (* 2002 added area from Seven Regions district *) '098' - Portage La Prairie RM '099' - Portage La Prairie City 'A33' - Dakota Tipi FN 'A05' - Dakota Plains FN 'A04' - Long Plain FN Carman (A2C) (* 2002 changed code from A2 to A2C *) '034' - Carman Town '033' - Dufferin RM '053' - Grey RM '112' - Roland RM '195' - St. Claude Village '158' - Thompson RM 1 Manitoba Regional Health Authority (RHA) DISTRICTS MCHP Area -

Rural Municipality of Pembina and Town of Manitou Amalgamation

As of 29 Sep 2021, this is the most current version available. It is current Le texte figurant ci-dessous constitue la codification la plus récente en for the period set out in the footer below. It is the first version and has not date du 29 sept. 2021. Son contenu était à jour pendant la période been amended. indiquée en bas de page. Il s'agit de la première version; elle n’a fait l'objet d'aucune modification. THE MUNICIPAL AMALGAMATIONS ACT LOI SUR LA FUSION DES MUNICIPALITÉS (C.C.S.M. c. M235) (c. M235 de la C.P.L.M.) Rural Municipality of Pembina and Town of Règlement sur la fusion de la municipalité Manitou Amalgamation Regulation rurale de Pembina et de la ville de Manitou Regulation 112/2014 Règlement 112/2014 Registered April 11, 2014 Date d'enregistrement : le 11 avril 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE DES MATIÈRES Section Article 1 Definitions 1 Définitions 2 New municipality established 2 Constitution d'une nouvelle municipalité 3 Boundaries 3 Limites 4 Status of new municipality 4 Statut de la nouvelle municipalité 5 Composition of council 5 Composition du conseil 6 Voters list 6 Liste électorale 7 Appointment of senior election official 7 Nomination du fonctionnaire électoral 8 Election expenses and contributions principal by-law 8 Règlement municipal sur les dépenses et 9 Application les contributions électorales 10 Term of office for members of first 9 Application council 10 Mandat des membres du premier conseil 11 Extension of term of office of old 11 Prolongation du mandat des membres councils des anciens conseils 12 Dissolution -

AUGUST 17 and 18 @ RIVERS, Manitoba

th th AUGUST 17 and 18 @ RIVERS, Manitoba Welcome to Rivers Rec Complex Order of events Friday 3pm penning set up 3:30pm onwards arrival of animals 5:00-7:00 pm culling committee 7:00pm Lamb supper -$15 Speaker David Hunt MAFRI- Premise ID workshop Saturday Pancake breakfast 10:00am Show starts Order -Youth, Jackpot, Commercials, Purebreds Wool show 2:00pm Sale Starts Auctioneer – Tyler Slawinski 2012 Champion Rookie Order of Sale: - Jackpot, commercials, Fleeces, Purebreds. The Canadian Sheep Breeders' Association is an organization of over 900 breeders of purebred sheep across Canada, representing over 40 breeds of sheep. The members of the Board of Directors of the Canadian Sheep Breeders' Association are elected by and represent purebred sheep organizations in each province. The CSBA is dedicated to working for the interests of sheep breeders across the country, whatever breed they may represent. Youth Show Adam Neuman age 13 Bethan Lewis age 13 Nelson Wilton age 14 Katy Neuman age 15 Mature ewe, yearling ewe, ewe lamb & showmanship. Market Lamb. Tall Spruce Farm Reg’d Polled Dorsets Icelandic and Commercial Sheep Also Available - fleeces, handspun yarn and hand-crafted wool items. Diana & Terry Neuman Box 463 McCreary, MB R0J 1B0 [email protected] 2 Proud to be a Canadian Family Owned and Operated Business Breaking New Ground Since The 1960's For over 40 years we have been providing customers of all sizes with Quality Products, Quality Service and Reliability. We are here to help you build your future in the livestock industry and supply all of your needs. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

2019 – 09 – Property Standards Maintenance

P a g e | 1 RIVERDALE MUNICIPALITY BY-LAW NO. 2019-09 ____________________________________________________ BEING A BY-LAW OF RIVERDALE MUNICIPALITY TO PROVIDE FOR THE MAINTENANCE OF PROPERTY WITHIN THE URBAN CENTRES OF THE MUNICIPALITY, INCLUDING RIVERS, CHIMO, WHEATLAND, BRADWARDINE, PARADISE VALLEY & ASPEN ROAD DEVELOPMENT __________________________________________________________ WHEREAS, The Municipal Act provides, in part, as follows: 232(1) A Council may pass by-laws for municipal purposes respecting the following matters… a) the safety, health, protection and well-being of people, and the safety and protection of property; c) subject to section 233, activities or things in or on private property; o) the enforcement of by-laws 232(2) Without limiting the generality of subsection (1), a council may in a by-law passed under this division… (a) regulate or prohibit; (d) establish fees or other charges for services, activities or things provided or done by the municipality or for the use of property under the ownership, direction, management or control of the municipality… 233 A by-law under clause 231(1)( c) (activities or things in or on private property) may contain provisions only in respect of a) the requirement that land and improvements be kept and maintained in a safe and clean condition; b) the parking and storing of vehicles, including the number and type of vehicles that may be kept or stored and the manner of parking and storing; c) the removal of top soil; and d) activities or things that in the opinion of the council are or could become a nuisance, which may include noise, weeds, odours, unsightly property, fumes or vibrations. -

Order No. 184/19 GILBERT PLAINS MUNICIPALITY GILBERT PLAINS RURAL WATER UTILITY REVISED RATES for JANUARY 1, 2020, JANUARY 1, 20

Order No. 184/19 GILBERT PLAINS MUNICIPALITY GILBERT PLAINS RURAL WATER UTILITY REVISED RATES FOR JANUARY 1, 2020, JANUARY 1, 2021, AND JANUARY 1, 2022 DECEMBER 12, 2019 BEFORE: Shawn McCutcheon, Panel Chair Marilyn Kapitany, BSc. (Hons), MSc., Panel Member Room 400 – 330 Portage Avenue 330, avenue Portage, pièce 400 Winnipeg, MB R3C 0C4 Winnipeg (Manitoba) Canada R3C 0C4 www.pubmanitoba.ca www.pubmanitoba.ca Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary..................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Background ................................................................................................................. 3 Water Supply/Distribution ........................................................................................... 3 Unaccounted for Water ............................................................................................... 4 3.0 Application ................................................................................................................... 4 Contingency Allowance and Utility Reserves .............................................................. 6 Working Capital Surplus/Deficit .................................................................................. 6 Cost Allocation Methodology ...................................................................................... 7 4.0 Board Findings ............................................................................................................ 9 Pass Through Rate Approval -

Municipal Officials Directory 2021

MANITOBA MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Municipal Officials Directory 21 Last updated: September 23, 2021 Email updates: [email protected] MINISTER OF MUNICIPAL RELATIONS Room 317 Legislative Building Winnipeg, Manitoba CANADA R3C 0V8 ,DPSOHDVHGWRSUHVHQWWKHXSGDWHGRQOLQHGRZQORDGDEOH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\7KLV IRUPDWSURYLGHVDOOXVHUVZLWKFRQWLQXDOO\XSGDWHGDFFXUDWHDQGUHOLDEOHLQIRUPDWLRQ$FRS\ FDQEHGRZQORDGHGIURPWKH3URYLQFH¶VZHEVLWHDWWKHIROORZLQJDGGUHVV KWWSZZZJRYPEFDLDFRQWDFWXVSXEVPRGSGI 7KH0XQLFLSDO2IILFLDOV'LUHFWRU\FRQWDLQVFRPSUHKHQVLYHFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQIRUDOORI 0DQLWRED¶VPXQLFLSDOLWLHV,WSURYLGHVQDPHVRIDOOFRXQFLOPHPEHUVDQGFKLHI DGPLQLVWUDWLYHRIILFHUVWKHVFKHGXOHRIUHJXODUFRXQFLOPHHWLQJVDQGSRSXODWLRQV,WDOVR SURYLGHVWKHQDPHVDQGFRQWDFWLQIRUPDWLRQRIPXQLFLSDORUJDQL]DWLRQV0DQLWRED([HFXWLYH &RXQFLO0HPEHUVDQG0HPEHUVRIWKH/HJLVODWLYH$VVHPEO\RIILFLDOVRI0DQLWRED0XQLFLSDO 5HODWLRQVDQGRWKHUNH\SURYLQFLDOGHSDUWPHQWV ,HQFRXUDJH\RXWRFRQWDFWSURYLQFLDORIILFLDOVLI\RXKDYHDQ\TXHVWLRQVRUUHTXLUH LQIRUPDWLRQDERXWSURYLQFLDOSURJUDPVDQGVHUYLFHV ,ORRNIRUZDUGWRZRUNLQJLQSDUWQHUVKLSZLWKDOOPXQLFLSDOFRXQFLOVDQGPXQLFLSDO RUJDQL]DWLRQVDVZHZRUNWRJHWKHUWREXLOGVWURQJYLEUDQWDQGSURVSHURXVFRPPXQLWLHV DFURVV0DQLWRED +RQRXUDEOHDerek Johnson 0LQLVWHU TABLE OF CONTENTS MANITOBA EXECUTIVE COUNCIL IN ORDER OF PRECEDENCE ............................. 2 PROVINCE OF MANITOBA – DEPUTY MINISTERS ..................................................... 5 MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ............................................................ 7 MUNICIPAL RELATIONS .............................................................................................. -

The Tale of Shoal Lake 40

The Tale of Shoal Lake 40 Shoal Lake 40 An Ojibway reserve located approximately a two hour drive from Winnipeg and Kenora, situated on the Western shore and peninsula of Shoal Lake, located on the Ontario-Manitoba border. Moved to a Peninsula, the Peninsula Was then Cut Off In 1919 a portion of Shoal Lake, including a burial ground, was annexed (which means taken) by the city of Winnipeg and the Shoal Lake 40 residents were relocated to the peninsula. An aqueduct was dug to provide Winnipeg with water, cutting off the Peninsula and rendering Shoal Lake 40 inaccessible. A dam was built to ensure that the city’s water remained pristine, while simultaneously leaving contaminated water on the reserve’s side. The reserve is located between Shoal Lake 39, which has access to clean water, and the reservoir of clean water for the City of Winnipeg, this has been a source of grievance and caused a general feeling of being forgotten. States of emergency have been declared in the past due to a high youth suicide rate. Residents have been left to cope with the situation as best they can. Water Advisory for Over Two Decades The Shoal Lake 40 First Nation’s approximately 285 residents have been living under a water advisory for over two decades. Finding solutions to the non-potable water that feeds the reserve is compounded by issues of access, and by the fact that the community is divided by the provincial boundary between Ontario and Manitoba. Shoal Lake 40 does not even have a water treatment facility. -

Rural Municipality of Lorne

NOTICE OF APPLICATION MUNICIPALITY OF LORNE REVISED WATER AND WASTEWATER RATES NOTRE DAME DE LOURDES UTILITY December 10, 2018 The Municipality of Lorne (Municipality) has applied to the Public Utilities Board (Board) for revised water and wastewater rates for Notre Dame de Lourdes Utility (Utility) as set out in By-Law No. 0032/18, read the first time on November 13, 2018. Rates were last approved in 2011 in Board Order No. 47/11. In addition to the revised rate application, the Municipality has also applied for the recovery of 2013-2019 Utility deficit by rate rider. The current and proposed rates are as follows: Current Proposed Rates Rates By-Law By-Law By-Law By-Law By-Law 0032/18 0032/18 0032/18 0032/18 70-10 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Quarterly Service Charge $ 6 .75 $ 7.96 $ 8.36 $ 8.76 $ 9.16 Water (per 1,000 gallons) $ 8 .35 $ 1 1.67 $ 1 2.77 $ 1 3.87 $ 1 4.98 Wastewater (per 1,000 gallons) $ 1 .71 $ 1.43 $ 1.33 $ 1.23 $ 1.14 Minimum Quarterly Charge* $ 36.93 $ 4 7.26 $ 5 0.66 $ 5 4.06 $ 5 7.52 Wastewater Only Customers** $ 22.14 $ 2 0.83 $ 2 0.33 $ 1 9.83 $ 1 9.42 Rate Rider (per 1,000 gallons)*** - $ 3.52 $ 3.52 $ 3.52 $ 3.52 *Based on 3,000 gallons **Based on 9,000 gallons ***The Municipality has a current deficit application before the Board for the rate rider of $3.52 for five years. -

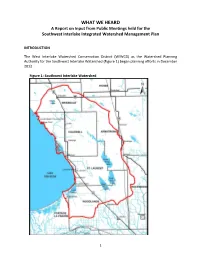

WHAT WE HEARD a Report on Input from Public Meetings Held for the Southwest Interlake Integrated Watershed Management Plan

WHAT WE HEARD A Report on Input from Public Meetings held for the Southwest Interlake Integrated Watershed Management Plan INTRODUCTION The West Interlake Watershed Conservation District (WIWCD) as the Watershed Planning Authority for the Southwest Interlake Watershed (Figure 1) began planning efforts in December 2013. Figure 1: Southwest Interlake Watershed 1 The WIWCD formed a Project Management Team to guide the development of the Southwest Interlake IWMP. The Project Management Team includes: Earl Zotter (Chair) Rural Municipality of St. Laurent Jack Cruise Rural Municipality of Armstrong Henry Rosing Rural Municipality of Woodlands Brian Sigfusson Rural Municipality of Coldwell Garth Asham Rural Municipality of Portage La Prairie Neil Brandstrom Rural Municipality of Eriksdale Linda Miller West Interlake Watershed Conservation District Patrick Watson Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship PUBLIC MEETINGS One of the first steps in the development of the plan was to hold public meetings to discuss what residents of the watershed value within the planning area. Four public meeting were held in May and June of 2014: May 18 – Lundar, May 20 – Eriksdale, May 27 – Lake Francis, and June 7 – St. Laurent. A total of 45 watershed residents attended the meetings. The discussions from these meetings are reported in this document and will provide direction to the Project Management Team on the scope and priorities of the plan. GATHERING INPUT At each of the public meetings, participants were asked to fill in worksheets. The worksheets included questions on what people felt were the main issues in the watershed, why they felt that these were priority issues, what they valued in the watershed, how they felt the issues could and should be addressed, and a number of other questions related to watershed management.