Its Nature, Structure and Functioning in Classical Yoga (2)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nixon, in France,11

SEE STORY BELOW Becoming Clear FINAL Clearing this afternoon. Fair and cold tonight. Sunny., mild- Red Bulk, Freehold EIMTION er tomorrow. I Long Branch . <S« SeUdlf, Pass 3} Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 173 RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 1969 26 PAGES 10 CENTS ge Law Amendments Are Urged TRENTON - A legislative lative commission investigat- inate the requirement that where for some of die ser- the Monmouth Shore Refuse lection and disposal costs in Leader J. Edward CrabieJ, D- committee investigating the ing the garbage industry. there be unanimous consent vices tiie authority offers if Disposal Committee' hasn't its member municipalities, Middlesex, said some of the garbage industry yester- Mr. Gagliano called for among the participating the town wants to and the au- done any appreciable work referring the inquiry to the suggested changes were left day heard a request for amendments to the 1968 Solid municipalttes in the selection thority doesn't object. on the problems of garbage Monmouth County Planning out of the law specifically amendments to a 1968 law Waste Management Authority of a disposal site. He said the The prohibition on any par- collection "because we feel Board. last year because it was the permitting 21 Monmouth Saw, which permits the 21 committee might never ticipating municipality con- the disposal problem is funda- The Monmouth Shore Ref- only way to get the bill ap- County municipalities to form Monmouth County municipal- achieve unanimity on a site. tracting outside the authority mental, and we will get the use Disposal Committee will proved by both houses of the a regional garbage authority. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Trouble Downloading Free Logic Everybody Album from Site Trouble Downloading Free Logic Everybody Album from Site

trouble downloading free logic everybody album from site Trouble downloading free logic everybody album from site. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67a40544c91f15f8 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Trouble downloading free logic everybody album from site. Logic – Everybody Full Album leak Download link MP3 ZIP RAR Logic - Everybody has it leaked?, Logic - Everybody album download, Logic - Everybody download album, Logic - Everybody download mp3 album, Logic - Everybody download zip, Logic - Everybody download, Logic - Everybody FULL ALBUM, Logic - Everybody has it leaked, Logic - Everybody LEAK ALBUM, Logic - Everybody leak, Logic Everybody download, Logic Everybody full album leaked download, Logic Everybody 320 kbps, Logic Everybody album, Logic Everybody album download, Logic Everybody album leaked. Artist: Logic Album: Everybody Year: 2017 Genre: East Coast Hip Hop, Hip Hop, Rap. Stream & Download Logic’s New 13-Track Album ‘Everybody’ Logic ’s new 13-track album Everybody is now available! The project brings on features from Run The Jewels’ Killer Mike, Juicy J, Khalid, Alessia Cara, famous scientist Neil deGrasse Tyson and more. -

The Golden Bough

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Ontario Council of University Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/goldenboughstudy04fraz THE GOLDEN BOUGH A STUDY IN MAGIC AND RELIGION THIRD EDITION r y C ' ' PART III THE DYING GOD V- MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA. Ltd. TORONTO THE DYING GOD J. G. FRAZER, D.C.L., LL.D.. Litt.D. FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE PROFESSOR OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL MACMILLAN AND CO, LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 191 I i iqii PREFACE With this third part of The Golden Bough we take up the question, Why had the King of the Wood at Nemi regu- larly to perish by the hand of his successor ? In the first part of the work I gave some reasons for thinking that the priest of Diana, who bore the title of King of the Wood beside the still lake among the Alban Hills, personated the great god Jupiter or his duplicate Dianus, the deity of the oak, the thunder, and the sky. On this theory, accordingly, we are at once confronted with the wider and deeper ques- tion, Why put a man-god or human representative of deity to a violent death ? Why extinguish the divine light in its earthly vessel instead of husbanding it to its natural close ? My general answer to that question is contained in the present volume. If I am right, the motive for slaying a man-god is a fear lest with the enfeeblement of his body in sickness or old age his sacred spirit should suffer a corresponding decay, which might imperil the general course of nature and with it the existence of his worshippers, who believe the cosmic energies to be mysteriously knit up with those of their human divinity. -

Headline of the Month: Headline of the Month

Headline of the Month: Legislators and Voters Alike Prepare For Midterm Elections This November By Sal DiMaggio It’s November and you know what that means. Midterms! No, no, not the tests. Don’t worry, those aren’t until January. But the midterm elections are important, and here’s why: The midterm elections are held every four years, right in the middle of a presidential term. Every member of the U.S. House of Representatives is up for reelection, as their terms are two years each, as well as 35 Senators, whose terms are six years. Some states also have their elections for governors during the midterms. Currently, the Republicans (R; GOP) have a 235-193 lead in the House, as well as a slight majority in the Senate, 51-49. They are hoping that they can keep this majority for the next two years. The Democrats (D), on the other hand, are looking to topple this control. These are the outcomes of both of those results: If the Republicans remain in power, Congress will most likely still be able to work with President Trump, who is also a Republican. This will result in many things on the Republican agenda to be accomplished. The Republicans aim to crack down on illegal immigration and to lower taxes in the next few years to come. Along with this, they plan to protect gun rights and denuclearize the Korean Peninsula. If the Democrats gain control, Congress and the president will often clash, as they will disagree on most issues, and few of the things on Trump’s to-do list will get done. -

Logic Ysiv Album Download Free Logic Ysiv Album Download Free

logic ysiv album download free Logic ysiv album download free. Automatically playing similar songs. To disable, switch Autoplay to ‘OFF’ under Settings. Explicit Content. Get Notified & Stay Up-to-date! Get Notified about the latest hits and trends, so that you are always on top of the latest in music when it comes to your friends. This will remove all the songs from your queue. Are you sure you want to continue? Clear currently playing song. Saudi Arabia Music. Trending. Language Selection. Please select the language(s) of the music you listen to. Released by Def Jam Recordings Sep 2018 | 14 Tracks. YSIV Songs. No track found found in this album. You may also like. YSIV is a English album released on Sep 2018. YSIV Album has 14 songs sung by Logic, Lucy Rose, The RattPack. Listen to all songs in high quality & download YSIV songs on Gaana.com. Related Tags - YSIV, YSIV Songs, YSIV Songs Download, Download YSIV Songs, Listen YSIV Songs, YSIV MP3 Songs, Logic Songs. Logic ysiv album download free. Add to Custom List. Add to My Collection. AllMusic Rating. Overview ↓ User Reviews ↓ Credits ↓ Releases ↓ Similar Albums ↓ facebook twitter tumblr. AllMusic Review by Andy Kellman. Logic had his biggest year yet in 2017. Everybody entered the Billboard 200 at number one, was certified gold within a month, and its "1-800- 273-8255" went Top Five pop and led to the rapper's first Grammy nominations. On the heels of those triumphs, Logic issued the commercial mixtape Bobby Tarantino II the following March -- just before Everybody went platinum -- and in six months struck again with the concluding fourth volume of his Young Sinatra series. -

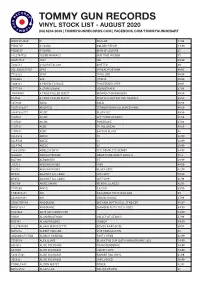

Vinyl Stock List - August 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | Tommygunrecords.Com | Facebook.Com/Tommygunhobart

TOMMY GUN RECORDS VINYL STOCK LIST - AUGUST 2020 (03) 6234 2039 | TOMMYGUNRECORDS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TOMMYGUNHOBART WARPLP302X !!! WALLOP 47.99 PIE027LP #1 DADS GOLDEN REPAIR 44.99 PIE005LP #1 DADS MAN OF LEISURE 35 8122794723 10,000 MANIACS OUR TIME IN EDEN 45 SSM144LP 1927 ISH 39.99 7202581 24 CARAT BLACK GHETTO 69 USI_B001655701 2PAC 2PACALYPSE NOW 49.95 7783828 2PAC THUG LIFE 49.99 FWR004 360 UTOPIA 49.99 5809181 A PERFECT CIRCLE THIRTEENTH STEP 49.95 6777554 A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK 67.99 JIV41490.1 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST MIDNIGHT MARAUDERS 49.99 R14734 A TRIBE CALLED QUEST PEOPLE'S INSTINCTIVE TRAVELS 69.99 5351106 ABBA GOLD 49.99 19075850371 ABORTED TERRORVISION COLOURED VINYL 49.99 88697383771 AC/DC BLACK ICE 49.99 5107611 AC/DC LET THERE BE ROCK 41.99 5107621 AC/DC POWERAGE 47.99 5107581 ACDC 74 JAIL BREAK 49.99 5107651 ACDC BACK IN BLACK 45 XLLP313 ADELE 19 32.99 XLLP520 ADELE 21 32.99 XLLP740 ADELE 25 29.99 1866310761 ADOLESCENTS THE COMPLETE DEMOS 34.95 LL030LP ADRIAN YOUNGE SOMETHING ABOUT APRIL II 52.8 M27196 AEROSMITH ST 39.99 J12713 AFGHAN WHIGS 1965 49.99 P18761 AFGHAN WHIGS BLACK LOVE 42.99 OP048 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2012-2017 59.99 OP053 AGAINST ALL LOGIC 2017-2019 61.99 S80109 AIMEE MANN MENTAL ILLNESS 42.95 7747280 AINTS 5,6,7,8,9 39.99 1.90296E+11 AIR CASANOVA 70 PIC DISC RSD 40 2438488481 AIR VIRGIN SUICIDE 37.99 SPINE799189 AIRBOURNE BREAKIN OUTTA HELL STND EDT 45.95 NW31135-1 AIRBOURNE DIAMOND CUTS THE B SIDES 44.99 FN279LP AK79 40TH ANNIV EDT 63.99 VS001 ALAN BRAUFMAN VALLEY OF SEARCH 47.99 M76741 ALAN PARSONS I -

Ysiv Download Free

ysiv download free Logic: 'YSIV' Mixtape Stream & Download - Listen Now! The 28-year-old rapper just dropped his latest mixtape – Young Sinatra IV ! YSIV is the fourth installment in Logic ‘s Young Sinatra series. His third installment Young Sinatra: Welcome to Forever came out back in 2013. “As a commercial now mainstream artist,” Logic said about the album. “I feel very proud in knowing that like Im dropping a boom-bap hip hop album. There’s not really too many people doing that, especially this way, very 90’s. This is a straight up a boom bap album on a commercial scale.” You can download Logic ‘s new mixtape off of iTunes here. Ysiv download free. 1) Select a file to send by clicking the "Browse" button. You can then select photos, audio, video, documents or anything else you want to send. The maximum file size is 500 MB. 2) Click the "Start Upload" button to start uploading the file. You will see the progress of the file transfer. Please don't close your browser window while uploading or it will cancel the upload. 3) After a succesfull upload you'll receive a unique link to the download site, which you can place anywhere: on your homepage, blog, forum or send it via IM or e-mail to your friends. Ysiv download free. Listen to this album in high quality now on our apps. Enjoy this album on Qobuz apps with your subscription. Enjoy this album on Qobuz apps with your subscription. Listen on Qobuz. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. -

October 4, 2018

October 4, 2018 Volume 99 Number 07 THE DUQUESNE DUKE www.duqsm.com PROUDLY SERVING OUR CAMPUS SINCE 1925 Cramped Kavanaugh hearing draws University campus attention across campus celebrates living leads Heritage to concerns Week Gabriella Dipietro Meredith Blakely news editor staff writer & Heritage Week is a three-day Hallie Lauer yearly event that celebrates all features editor things Duquesne. The univer- sity was founded 140 years ago This is the first article in the on Oct. 1, 1878. This year marks Duke Deep Dives series. For the 6th annual Heritage Week more on the series, see the Staff that commemorates Duquesne’s Editorial on page 4. birthday and the university’s Duquesne students are Catholic Spiritan heritage. complaining about the cramped Each year, Duquesne celebrates living situation on campus, since Heritage Week beginning on many of them reside in forced Monday, Oct. 1 and concluding on triples or quads. Wednesday, Oct. 3. These three To some it seems that students days were full of celebration, such are paying more money for less as the university birthday party living space. From 2017 to 2018, on A-Walk on Monday, which fea- tuition has increased across the tured three tables including food, whole university by 3.6 percent. free T-shirts and games. During the 2017 academic Tuesday’s events included a year, the university, which had Mass celebrating the Feast Day an occupancy rate of 102 percent, of Claude Poullart de Places, a housed 3,784 students on campus Katia Faroun/Photo Editor Feast Day Luncheon and a “Feast see DORMS — page 2 Duquesne University law students gathered outside of Coffee Tree Roasters on Thursday, Sept. -

UDSSHOOTING CRAP HAHED M IO COURT on ( M M on Mwm

15!.^ WmM: ii^ifeaa?|ps m i PI' p i .*--2 vr-ii .IRJII DAILY CIEOtJLATIOIt i # '! t i a B BVBNIKG HBBALD »J m <fibr '<lk« montti of FetoiiaiTi 19M, 3e*A ;fV^ -<.%" »wWrs5i,*X % ,6 9 0 f,C/ ii^ 1m .•k,:b' *.r»' •■i^% rnimmim >;»; - p V i i *'l len-l-S’da V0L»XLnTnN0.152. CUssliled AdTertislng on Page A >r^s; ■ o i i i ^ a i ^ : f- : 7 't'f "'ir-'' T COOLIDGE BANS P o^ W as'Ajl^^ : 4 : I W O P O U C M N EASTER ‘‘SHAKES” BR0ADCAS1IRS fomaif; V KILLED No More Handclasps by Presi OPMWARFJUffi A 6 A 6 i rr .Sho^/ Himsolf iQ tE RESIGN TO dent for Tourist Companies m t Stolen in Looting to Advertise. O N ( m m o f S k k e i t a BUSINESS Washington, March 29.— O N mWM -March 29.— Au; i ' >■''■ President Coolldge has called ' alllfed i eleven-year-eld burg a halt on handkshaking with lar slwt and kilted himself r J i : the thousands of tourists who hdre today when a gun, said by % d Intends Handing in annually visit Washington Seek Change in C o p y ri^ IM e iQ o re Mob F # Oiit ppllne to' kave been stolen, was of E n { ^ around Easter time, it was a<^dentally discharged as be learned today. taw— Claim High Charges Orer Loot-Pefice B ^ r e was sneaking home over a Resignation Soon— None The White House Is dally back fence. Declares Scientist turning down many requests The fioy was Steve Mogyor- from large delegations of Have Driven Two Stations Gang Qdef Is NotPhiing dy. -

Plato, with an English Translation

Presented to THE LIBRARY of VICTORIA UNIVERSITY Toronto by The late Dr. Carleton Stanley THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY EDITED BY E. CAPPS. PH.n., IX.D. T. E. PAGE, utt.d. W. H. D. ROUSE, LHT-D. PLATO PLATO WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION X LAWS R. G. BURY, Lm.D. rORMKRLT SCHOLAR OF TRISTTT COLLEGF, CAMBRISOX IN TWO VOLUMES II LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN NEW YORK : G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXVI i2 1. 2 op. 3 Printed in &rea( Britain. 48846 CONTEXTS PAQK BOOK VII 3 BOOK VIII 125 BOOK IX 199 BOOK X 297 BOOK XI 389 BOOK XII 475 INDEX 571 \ LAWS NOMOI TA TOY AIAAOrOY DPOSfinA A0HNAIO2 HEN02, KAEINIA2 KPH2, MEriAAOS AAKEAA1M0NI02 788 A0. Tevo/xevcov Be iraihoiv appevwv kuI Orfkuwv Tpo(f>T)V flip TTov Kol TTaiSeiav TO fxera ravra Xeyeiv opdorar av ^ 'yl'yvoiO^ rj/xlv, fjv elvai fxev apprjTOv iravTox; aSvvarov, Xeyo/xevr) Sk SiSaxfj rivl Kal vovOerijaei fidWov rj v6/j,oi<i sIkvV av r)pZv (paivoiTO. IBla jap Kal Kar oIklu^ iroWa Kal afiiKpa Kal ovk €K(f)avr] irdai yiyvofieva paBico^ VTTO T^9 eKaarcov Xvinj'i re Kal rjBovrj^; B Kal i7n6vfj,ia<;, erepa irapa Ta<i tov vofModerov ^u/u,^ovXa<i Trapayevofieva iravroBaTra Kal ov'^ onoia dXkrj\oi,<i aTrepyd^oir^ av to, tmv ttoXitcov •tjOr]' Tovro Be kukov rai<; TroXeai. Kal yap Bia a/xiKporrfTa avTtov Kal irvKvoTrjTa e7n^7]/jLia ri- Oevra iroieiv v6/j,ov<; aTrpeTre? dp.a Kal da^rjp-ov. BiacfyOetpei Be Kal rov<; ypacpf] redevra^ v6fiov<;, ev T0t9 (TfiiKpoi<; Kal TrvKvoit i6icr0evT(ov tcou C dvdpcoiroyv irapavofxetv Sore diropia fiev irepl avrd vofiodeTelv, aiyav Be dBvvarov. -

Vinyl News 1. Quartal 2019 HP.Xlsx

Artist Title Units Media Genre Release A MODE OF DUST II 1 LP AMB 01.03.2019 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH WHEN THE WORLD.. -HQ- 2 LP HM. 17.01.2019 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH WHEN THE.. -COLOURED- 3 LP HM. 17.01.2019 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS FUZZ CLUB SESSION 1 LP ROC 15.02.2019 A SECRET REVEALED SACRIFICES -GATEFOLD- 2 LP PUN 25.01.2019 A SWARM OF THE SUN WOODS -GATEFOLD- 1 LP ROC 10.01.2019 AARON 7-JOS VOIS 1 12in POP 25.01.2019 ABANDONED KILLED BY FAITH -REISSUE- 1 LP PUN 10.01.2019 ABERNATHY, AARON EPILOGUE 2 LP SOU 01.02.2019 ABRUPTUM VI SONUS VERIS NIGRAE MAL 2 LP EXP 25.01.2019 ABSENT TOWARDS THE VOID 1 LP ROC 31.01.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE ROVANIEMI 1993 -COLOURED- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE ROVANIEMI 1993 -LTD- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE SIMPUKK.. -COLOURED- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 ABSOLUUTTINEN NOLLAPISTE SIMPUKKA-AMPPELI -LTD- 2 LP ROC 22.02.2019 AC/DC IN THE BEGINNING 1 LP ROC 03.01.2019 ACACIA STRAIN CONTINENT -COLOURED/LTD- 1 LP HC. 18.01.2019 ACACIA STRAIN CONTINENT -COLOURED/LTD- 1 LP HC. 18.01.2019 ACETONE 1992-2001 2 LP ROC 17.01.2019 ACETONE 1992-2001 -GATEFOLD- 2 LP ROC 25.01.2019 ACHILIFUNK SOUND SYSTEM CASIOPONY 1 LP FNK 18.01.2019 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE SACRED AND INVIOLABLE.. 1 LP ROC 15.02.2019 ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE & THE MELTING PARAISO U.F.O.