A War Against Garbage in Postwar Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

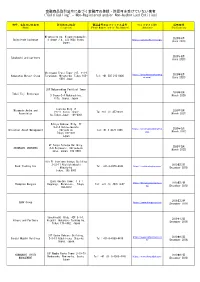

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered And/Or Non-Authorized Entities)

金融商品取引法令に基づく金融庁の登録・許認可を受けていない業者 ("Cold Calling" - Non-Registered and/or Non-Authorized Entities) 商号、名称又は氏名等 所在地又は住所 電話番号又はファックス番号 ウェブサイトURL 掲載時期 (Name) (Location) (Phone Number and/or Fax Number) (Website) (Publication) Miyakojima-ku, Higashinodamachi, 2020年6月 SwissTrade Exchange 4-chōme−7−4, 534-0024 Osaka, https://swisstrade.exchange/ (June 2020) Japan 2020年6月 Takahashi and partners (June 2020) Shiroyama Trust Tower 21F, 4-3-1 https://www.hamamatsumerg 2020年6月 Hamamatsu Merger Group Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105- Tel: +81 505 213 0406 er.com/ (June 2020) 0001 Japan 28F Nakanoshima Festival Tower W. 2020年3月 Tokai Fuji Brokerage 3 Chome-2-4 Nakanoshima. (March 2020) Kita. Osaka. Japan Toshida Bldg 7F Miyamoto Asuka and 2020年3月 1-6-11 Ginza, Chuo- Tel:+81 (3) 45720321 Associates (March 2021) ku,Tokyo,Japan. 104-0061 Hibiya Kokusai Bldg, 7F 2-2-3 Uchisaiwaicho https://universalassetmgmt.c 2020年3月 Universal Asset Management Chiyoda-ku Tel:+81 3 4578 1998 om/ (March 2022) Tokyo 100-0011 Japan 9F Tokyu Yotsuya Building, 2020年3月 SHINBASHI VENTURES 6-6 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku (March 2023) Tokyo, Japan, 102-0083 9th Fl Onarimon Odakyu Building 3-23-11 Nishishinbashi 2019年12月 Rock Trading Inc Tel: +81-3-4579-0344 https://rocktradinginc.com/ Minato-ku (December 2019) Tokyo, 105-0003 Izumi Garden Tower, 1-6-1 https://thompsonmergers.co 2019年12月 Thompson Mergers Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Tel: +81 (3) 4578 0657 m/ (December 2019) 106-6012 2019年12月 SBAV Group https://www.sbavgroup.com (December 2019) Sunshine60 Bldg. 42F 3-1-1, 2019年12月 Hikaro and Partners Higashi-ikebukuro Toshima-ku, (December 2019) Tokyo 170-6042, Japan 31F Osaka Kokusai Building, https://www.smhpartners.co 2019年12月 Sendai Mubuki Holdings 2-3-13 Azuchi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tel: +81-6-4560-4410 m/ (December 2019) Osaka, Japan. -

Exploring Japanese Culture

Event calendar i n S U G I N A M I T O K Y O Events are subject to cancellation or change. Please check with the organizer for the latest information. Exploring Spring Japanese Culture in ●Koenji Street ●Asagaya SUGINAMI TOKYO Performance Festival Bar-hopping Festival with Map Summer ●Asagaya Tanabata Festival P20-21 ●Tokyo Koenji Awaodori Festival P20-21 Autumn ●Asagaya Jazz Street ●Koenji Festival ●Suginami Festa ●Asagaya Bar-hopping Festival ●Ogikubo ●Trolls in the Park Classical Music Festival (Outdoor Art Festival) Winter ●Koenji Engei Festival JR Yamanote Line Suginami Ward Ikebukuro Kami Shimo Igusa Iogi Igusa Route Seibu-Shinjuku Line Chart JR Chuo Sobu Line 80min Narita Express Nishi Shinjuku Mitaka Kichijoji Ogikubo Ogikubo Asagaya Koenji Nakano NARITA Kugayama Minami Shin Higashi AIRPORT Asagaya Koenji Koenji Tokyo Metro Attention: JR Line Fujimigaoka Marunouchi Line 35min Keio Inokashira Keio Line Shibuya Limousine bus Chuo line express Line It does not stop at Koenji, Asagaya, or Nishi-Ogikubo Takaido Hamada Stations on weekends & holidays. -yama Nishi HANEDA Eifuku Eifuku Chuo Sobu line local Cho Meidai AIRPORT It stops at all stations unless terminating at Nakano. -mae Kami Igusa Seibu-Shinjuku Iogi Line Shimo Igusa Due to COVID-19, opening hours of stores may dier. P14 Genro We recommend checking their latest information before visiting. Suginami The information in this booklet is accurate as of March Map 2021. P22 Igusa Hachimangu Shrine P6 Kosugi-Yu P16 Tokyo Polytechnic University Suginami Animation Museum P22 Asagaya -

Adachi-Ku Nerima-Ku Setagaya-Ku Suginami-Ku Itabashi-City Minato

2. 基本 的事 項等 Mapof Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Ove rflowof (1) 作成(1) 主体 東 京 都 (2) 指(2) 定年 月日 令 和 元 年 5月23日 theShakujii Rive of r the Arakawa Rive System r (3) 告示番号(3) 東 京 都告示第55号 (4) 指(4) 定の 根 拠 法令 水 防法(昭和 24年法律 第193号)第14条第2項 (inundation duration) (5) 対象とな(5) る 水 位 周知河 川 ・荒川 水 系石神井 川 (実施 区間:下 表に示す通り) (6) 指(6) 定の 前提 とな る 降雨 石神井 川 流 域 の 1時間最 大雨量153mm 1. About this map 2. Basic information 24時間総雨量690mm Locationmap (1) Pursuant to the provisions of the Flood Control Act, this map shows the duration of inundation for the maximum assumed (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government 【問い合わせ先 】 rainfall for sections those subject to water-level notification of the Shakujii River of the Arakawa River System. (2) Map created on May 23, 2019 東 京 都建 設局 河 川 部防災課 03-5321-1111(代) (2) This river flood risk map shows the estimated duration of 50cm or deeper inundation that occurs due to overflow of the (3) Released as TMG announcement No.55 Shakujii River of the Arakawa River System resulting from the maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the time of the map's publication. (4) Designation made based on Article 14, paragraph 2 of the Flood Control Act SumidaRive r (Act No. 193 of 1949) (3) Because the simulation does not take into account flooding of tributaries or flooding caused by rainfall greater than ShakujiiRive r the assumed level, by a storm surge, or by runoff of rainwater, the actual duration of inundation may differ from the (5) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Shakujii River of the Arakawa River System estimates and inundation may also occur in areas not indicated on this map. -

Exploring Japanese Culture In

JR Yamanote Line Suginami Ward Ikebukuro Kami Shimo Igusa Iogi Igusa Route Seibu-Shinjuku Line Chart JR Chuo Sobu Line 80min Narita Express Nishi Shinjuku Mitaka Kichijoji Ogikubo Ogikubo Asagaya Koenji Nakano NARITA Kugayama Minami Shin Higashi AIRPORT Asagaya Koenji Koenji Tokyo Metro Attention: JR Line Fujimigaoka Marunouchi Line 35min Keio Inokashira Keio Line Shibuya Limousine bus Chuo line express Line It does not stop at Koenji, Asagaya, or Nishi-Ogikubo Takaido Hamada Stations on weekends & holidays. -yama Nishi HANEDA Eifuku Eifuku Chuo Sobu line local Cho Meidai AIRPORT It stops at all stations unless terminating at Nakano. -mae Due to COVID-19, opening hours of stores may dier. We recommend checking their latest information before visiting. Suginami The information in this booklet is accurate as of March Map 2021. Ogikubo P28 Physical Space Academy Ogikubo Tokyo Metro Marunouchi Line 2 3 Kosugi-Yu Open hours: 15:30-1:45 * On Saturday and Sunday, 8:00-1:45 Closed on Thursday Address: 3-32-2, Koenji-Kita, Suginami Web: https://kosugiyu.co.jp/ Twitter: @kosugiyu Instagram: @kosugiyu_sento Facebook: @kosugiyu Tamano-Yu Open hours: 15:00-1:00 Closed on Monday and Tuesday Address: 1-13-7, Asagaya-Kita, * Standard Tokyo sento fee: ¥470 for an adult, ¥180 for up to12yrs, Sento - Public Bathhouse ¥80 for up to 6yrs The history of sento, public bathhouses, goes as far back It has been said that various other subjects were taboo, as the 6th century, originating as part of temple culture in such as monkeys (” saru” in Japanese, a homonym for the Japan. -

Ministry of the Environment

List of Public Service Corporations under the Jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Environment ●Public Service Corporations (selected) (As of April 2001) Name of the corporation Address of the main office Telephone number <Under supervision of the Minister’s Secretariat> Environmental Information Center 8F, Office Toranomon1Bldg., 1-5-8 Toranomon, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0001 03-3595-3992 Earth, Water and Green Foundation 6F, Nishi-shinbashi YK Bldg., 1-17-4 Nishi-shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 03-3503-7743 <Under supervision of the Waste Management and Recycling Department> Ecological Life and Culture Organization (ELCO) 6F, Sunrise Yamanishi Bldg., 1-20-10 Nishi-shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0003 03-5511-7331 Japan Environmental Sanitation Center 10-6 Yotsuya-kamicho, Kawasaki-ku, Kawasaki-shi, Kanagawa Prefecture 210-0828 044-288-4896 The National Federation of 4F, Daini-AB Bldg., 3-1-17 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-0032 03-3224-0811 Industrial Waste Management Associations Japan Industrial Waste Technology Center 2F, Nihonbashi Koa Bldg., 2-8-4 Nihonbashi-horidomecho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0012 03-3668-6511 Japan Industrial Waste Management Foundation Sakura Shinbashi Bldg., 2-6-1 Shinbashi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0004 03-3500-0271 All Japan Private Sewerage Treatment Association 7F, Tokyo Yofuku Kaikan, 13 Ichigaya-hachimancho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-0844 03-3267-9757 Japan Education Center of Environmental Sanitation 2-23-3 Kikukawa, Sumida-ku, Tokyo 130-0024 03-3635-4880 Waste Water Treatment Equipment Engineer Center Kojimachi 4-chome Bldg., 4-3 Kojimachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 102-0083 03-3237-6591 Japan Sewage Works Association 1F, Nihon Bldg., 2-6-2 Otemachi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0004 03-5200-0811 Japan Waste Management Association 7F, IPB Ochanomizu, 3-3-11 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033 03-5804-6281 Japan Sewage Treatment Plant Operation and 5F, Sakura Bldg., 1-3-3 Uchikanda, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 101-0047 03-5281-9291 Maintenance Association, INC. -

Suginami Guide Book

SUGINAMI GUIDE BOOK Quick City Overview 1 2 Suginami City in Numbers Intention to Settle Find it Easy to Live Here Population 574,280 No. of Households 325,518 87.6% 96.1% * According to 2019 Suginami Population Pyramid 100+ City residential opinion survey 95~99 Male 90~94 Female 85~89 Suginami City 80~84 75~79 70~74 65~69 60~64 No. of Trees 55~59 35,914 50~54 45~49 40~44 1st 35~39 Cherry Blossom 5,945 30~34 Area ㎢ 25~29 34.06 20~24 2nd 15~19 Japanese Zelkova 5,373 10~14 5~9 0~4 3rd Ginkgo 3,499 25000 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 0 5000 10000 15000 2000025000 (people) (people) * According to FY2017 Suginami City greenery fact- ¿QGLQJVXUYH\ 100+ 95~99 Male 90~94 Female Green Space Ratio 85~89 Japan 80~84 No. of Parks 75~79 % 70~74 327 21.77 65~69 *As of April 1, 2019 60~64 * According to FY2017 55~59 Suginami City greenery fact- 50~54 ¿QGLQJVXUYH\ 45~49 40~44 Park Area per Person 35~39 ㎡ 30~34 2.07 25~29 20~24 *As of April 1, 2019 15~19 10~14 5~9 0~4 The smallest 5000005 0004 0 000300340 20000200 10000100 010 00 10000 02000 002 300003 400004 5005000 (万人) As of(万人) October 2019 amount out of all Daily Amount of Garbage Generated per Resident 23 Special Wards for 8 years running! No. of Children Max. No. of Children Allowed to g/day Total Fertility Rate 466 (under age 15) enter the Certi ed Child Care Center *FY2018 No waiting list for childcare 60,323 1.03 12,080 since FY2018! * According to 2018 Tokyo *As of April 1, 2019 metropolitan demographic No. -

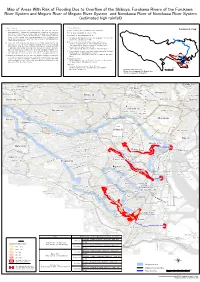

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River of Nomikawa River System (estimated high rainfall) 1. About this map 2. Basic information Location map (1) Pursuant to the provisions of the Flood Control Act, this map shows the (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government areas expected to flood and anticipated depth of inundation that can occur (2) Risk areas designated on June 27, 2019 when there is the level of rainfall used as a basis for flood control measures for sections subject to flood warnings of the Shibuya, Furukawa (3) Released as TMG announcement No.162 Rivers of the Furukawa River System and Meguro River of Meguro River (4) Designation made based on Article 14, paragraph 2 of the Flood System and those subject to water-level notification of the Nomikawa River Control Act (Act No.193 of 1949) of Nomikawa River System. (5) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map (2) This river flood risk map uses a simulation to show inundation that can Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa River System occur due to overflow of the Shibuya, Furukawa Rivers of the Furukawa Sumida River (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) River System and Meguro River of Meguro River System and Nomikawa River Meguro River of Meguro River System of Nomikawa River System resulting from the level of rainfall used as a (The flood warning section is shown in the table below.) basis for flood control measures with an annual exceedance probability of 1 percent. -

Now(PDF:1427KB)

Okutama Minumadai- Okutama Town Shinsuikoen Ome City Yashio Ome IC Nishi- Ome Takashimadaira Adachi Tokorozawa Ward Wakoshi Daishi- Matsudo Okutama Lake Kiyose City Mae Rokucho Mizuho Town Shin- Akitsu Narimasu Akabane Akitsu Kita-Ayase Nishi-Arai Hakonegasaki Kanamachi Hamura Higashimurayama Itabashi Ward City Tama Lake Kita Ward Higashimurayama City Hikarigaoka Ayase Shibamata Higashiyamato Kumano- Kita- Higashikurume Oji Mae Senju Katsushika Hinode Town Musashimurayama City Nerima Ward Arakawa City Hibarigaoka Ward City Kamikitadai Shakujiikoen Kotakemukaihara Ward Keisei-Takasago Kodaira Toshimaen Toshima Aoto the changing Musashi-itsukaichi Hinode IC Fussa City Yokota Ogawa Nishitokyo City Ward Air Base Tamagawajosui Nerima Nishi- Tamagawajosui Kodaira City Tanashi Ikebukuro Nippori Akiruno City Ichikawa Tachikawa City Kamishakujii Nippori Haijima Bunkyo Taito Ward Akiruno IC Saginomiya Moto-Yawata Showa Kinen Ward face of tokyo Park Nakano Ward Takadanobaba Shin-Koiwa Kokubunji Koganei City Musashino City Ueno City Ogikubo Nakano Musashi-Sakai Mitaka Kichijoji Sumida Ward Akishima City Nishi-Kokubunji Nishi-Funabashi Kagurazaka Akihabara Kinshicho Hinohara Village Kokubunji Suginami Ward Tachikawa Kunitachi Nakanosakaue Shinjuku Ward Ojima Mitaka City Edogawa Ward City Kugayama Shinjuku Chiyoda Ward Sumiyoshi Hachioji-Nishi IC Honancho Fuchu City Akasaka Tokyo Funabori Tokyo, Japan’s capital and a driver of the global economy, is home Meiji Detached Fuchu Yoyogi- Shrine Hino City Chofu Airport Chitose- Meidai-Mae Palace Toyocho to 13 million people. The city is constantly changing as it moves Hachioji City Uehara Shinbashi Takahatafudo Fuchu- Karasuyama Shibuya Koto Ward Kasai Honmachi Shimotakaido steadily toward the future. The pace of urban development is also Keio-Hachioji Ward Urayasu Shimokitazawa Shibuya Chofu Kyodo Hamamatsucho Toyosu Yumenoshima accelerating as Tokyo prepares for the Olympic and Paralympic Hachioji Gotokuji Naka- Minato Chuo Park Kitano Hachioji JCT Tama Zoological Seijogakuen- Meguro Ward Ward Games in 2020 and beyond. -

Shinjuku Rules of Play

Shinjuku Rules of Play Gary Kacmarcik Version 2 r8 Tokyo is a city of trains and Shinjuku is the busiest In Shinjuku, you manage one of these con- train station in the world. glomerates. You need to build Stores for the Customers to visit while also constructing the rail Unlike most passenger rail systems, Tokyo has lines to get them there. dozens of companies that run competing rail lines rather than having a single entity that manages rail Every turn, new Customers arrive looking to for the entire city. Many of these companies are purchase a specific good. If you have a path to a large conglomerates that own not only the rail, but Store that sells the goods they want, then you also the major Department Stores at the rail might be able to move those new Customers to stations. your Store and work toward acquiring the most diverse collection of Customers. Shinjuku station (in Shinjuku Ward) expands down into Yoyogi station in Shibuya Ward. A direct rail connection exists between these 2 stations that can be used by any player. Only Stores opened in stations with this Sakura icon may be upgraded to a Department Store. Department Store Upgrade Bonus tokens are placed here. The numbers indicate the total number of customers in the Queue (initially: 2). Customer Queue New Customers will arrive on the map from here. Stations are connected by lines showing potential Components future connections. These lines cannot be used until a player uses theE XPAND action to place track Summary on them, turning them into a rail connection. -

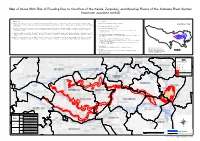

Map of Areas with Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Kanda, Zenpukuji, and Myoshoji Rivers of the Arakawa River System (Maximum Assumed Rainfall)

Map of Areas With Risk of Flooding Due to Overflow of the Kanda, Zenpukuji, and Myoshoji Rivers of the Arakawa River System (maximum assumed rainfall) 1. About this map 2. Basic information (1) Pursuant to the provisions of the Flood Control Act, this map shows the areas expected to flood and anticipated depth of inundation when the maximum assumed (1) Map created by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government rainfall occurs, for sections subject to flood warnings and those subject to water-level notification of the Kanda, Zenpukuji, and Myoshoji rivers of the Arakawa Location map River system. (2) Risk areas designated on March 30, 2018 (2) This river flood risk map uses a simulation to show inundation that can occur due to overflow of the Kanda, Zenpukuji, and Myoshoji rivers resulting from the (3) Released as TMG announcement No.449 maximum assumed rainfall. The simulation is based on the situation of the river channels and flood control facilities as of the time they were designated as areas expected to flood. (4) Designation made based on Article 14, paragraph 1 of the Flood Control Act (Act No.193 of 1949) (3) Because the simulation does not take into account flooding of tributaries or flooding caused by rainfall greater than the assumed level, by a storm surge, or by Sumida River runoff of rainwater, inundation may occur in areas other than those designated in this river flood risk map and the depths of flood water may differ from the (5) River subject to flood warnings covered by this map Ekoda River estimates. Kanda River of the Arakawa River system (The flood warning section is shown in the Myoshoji River Kanda River table below.) Zenpukuji River (4) This river flood risk map only takes into account overflow of the Kanda, Zenpukuji, and Myoshoji rivers. -

Supplemental Materials For

Supplemental materials for: Aoki T, Yamamoto Y, Ikenoue T, et al. Social isolation and patient experience in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(5):393-398. Appendix 1. Characteristics of participating clinics Clinic ID Location Municipality population 1 Kuroishi City, Aomori Prefecture 34,284 2 Iwate Town, Iwate Prefecture 13,692 3 Fujimino City, Saitama Prefecture 110,970 4 Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture 1,475,213 5 Koganei City, Tokyo 121,396 6 Suginami Ward, Tokyo 563,997 7 Kita Ward, Tokyo 341,076 8 Adachi Ward, Tokyo 670,122 9 Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture 2,295,638 10 Tsu City, Mie Prefecture 279,886 11 Yonago City, Tottori Prefecture 149,313 12 Izumo City, Shimane Prefecture 171,938 13 Iyo City, Ehime Prefecture 36,827 14 Arakawa Ward, Tokyo 212,264 15 Arakawa Ward, Tokyo 212,264 16 Kita Ward, Tokyo 341,076 17 Maebashi City, Gunma Prefecture 336,154 18 Hachinohe City, Aomori Prefecture 231,257 19 Fukushima City, Fukushima Prefecture 294,247 20 Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture 1,475,213 21 Kawasaki City, Kanagawa Prefecture 1,475,213 22 Adachi Ward, Tokyo 670,122 23 Suginami Ward, Tokyo 563,997 24 Higashi Oosaka City, Oosaka Prefecture 502,784 25 Aomori City, Aomori Prefecture 287,648 26 Kyoto City, Kyoto Prefecture 1,475,183 27 Konan City, Shiga Prefecture 54,289 28 Fukuchiyama City, Kyoto Prefecture 78,935 1 Supplemental Appendix 2. Item contents of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6) FAMILY: Considering the people to whom you are related by birth, marriage, adoption, etc.. -

2013 Laureate Toyo Ito Japan Sponsored by the Hyatt Foundation the Following Pages Contain Images of the Architecture of Toyo Ito

2013 Laureate Toyo Ito Japan Sponsored by The Hyatt Foundation The following pages contain images of the architecture of Toyo Ito. On the PritzkerPrize.com web site, these photos are linked to high resolution images that may be used for printing or broadcast in relation to the announcement of Toyo Ito being named the 2013 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate. The photographer/photo libraries/artists must be credited if noted. High resolution images may be downloaded for printing in newspapers, magazines, and other media. All photos are courtesy of Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects. 2 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito Toyo Ito, Photo by Yoshiaki Tsutsui White U (house) 1975—76 Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan Photo by Koji Taki 4 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, White U (house), 1975—1976, Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan Photo by Koji Taki Photo by Tomio Ohashi Photo by Tomio Ohashi 5 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, White U (house), 1975—1976, Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan Silver Hut (house) 1982 —1984 Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan Photos by Tomio Ohashi 6 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, Silver Hut (house), 1982 —1984, Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan Tower of Winds 1986 Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa, Japan Photo by Tomio Ohashi 7 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, Tower of Winds, 1986, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa, Japan Yatsushiro Municipal Museum 1988 —1991 Yatsushiro-shi, Kumamoto, Japan Photo by Tomio Ohashi 8 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, Yatsushiro Municipal Museum, 1988 —1991, Yatsushiro-shi, Kumamoto, Japan Dome in Odate (multipurpose dome) 1993—1997 Odate-shi, Akita, Japan Photos by Mikio Kamaya 9 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, Dome in Odate (multipurpose dome), 1993—1997, Odate-shi, Akita, Japan Sendai Mediatheque 1995—2000 Sendai-shi, Miyagi, Japan Photos by Tomio Ohashi 10 The Pritzker Architecture Prize 2013 Laureate Toyo Ito, Sendai Mediatheque, 1995—2000, Sendai-shi, Miyagi, Japan Photos by Nacasa & Partners Inc.