E:\GIDR\WORKING PAPERS\Working

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

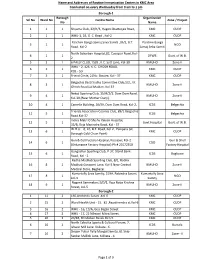

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Purchaser DEED OF

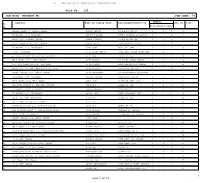

Siddhant Vincom LLP & Ors Owners And M/S Surreal Realty LLP Developer And _________________________ Purchaser DEED OF CONVEYENCE RE: Flat No. ______ , _ ___Floor, at“ WINDSOR THE RESIDENCE ” at 170D Picnic Garden Road, Kolkata 700039. Meharia Reid & Associates 9, Old Post Office Street, Ground Floor Kolkata 700001 THIS DEED OF CONVEYENCE made this _____ day of __________ 2018 BETWEEN M/S Sidhant Fincom Private Limited (PAN: AAECS4870R) and M/S Palak Mercantile Private Limited (PAN: AABCP6852H), both companies formed under the Companies Act of 1956 and having their registered offices at 40, Strand Road, P. O. & P. S. Burrabazar Kolkata 700001, represented by its Constituted attorney Mr. Manoj Poddar, son of Late Mr. C. K. Poddar, residing at 5A, Old Ballygunge, 2nd Lane, P. S. Karaya, P. O. Ballygunge, Kolkata 700019 (PAN: AERPP5136P), hereinafter referred to as the ‘OWNERS’ of the FIRST PART; AND M/s Surreal Realty LLP (PAN: ACWFS7460C), a Limited Liability Partnership formed and governed under the LLP Act of 2008 and having its registered office at Janki Mansion, 2nd Floor, 77/1A, P.O & P.S-Park Street, Kolkata 7000016, represented by Designated partner Mr. Manoj Poddar, son of Late Mr. C. K. Poddar, residing at 5A, Old Ballygunge, 2nd Lane, P. S. Karaya, P. O. Ballygunge, Kolkata 700019 (PAN: AERPP5136P)hereinafter referred to as the ‘DEVELOPER’ (which expression shall unless excluded by or repugnant to the subject or context shall mean and include its successor and/or successors in office) of the SECOND PART; AND ________________________ (PAN: ____________________) son of _______________________ residing at __________________ By Religion: Hindu, Nationality: Indian, Occupation: Business P. -

Ward No: 105 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

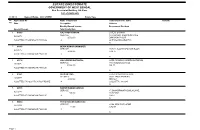

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 105 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 RAMLAL BAZAR 50 RAMLAL BAZAR AARATI GHOSH LT.PARESH GHOSH 2 3 5 1 2 JADAVGARH 1/59 JADAVGARH ABHIJIT MONDAL LATE GOURANGA CH MONDAL 3 1 4 2 3 HALTU 2/30 SUCHETA NAGAR ADHAR SADDAR LT BIPIN SADDAR 1 1 2 3 4 SAHID NAGAR 8/22 SAHID NAGAR ADHIR DUTTA LATE ABINASH DUTTA 1 3 4 4 5 JADAVGARH 3/50 JADAVGARH AJAY SAHA AKUL CH. SAHA 1 2 3 6 6 8/20 JADAVGARH AJIT CHAKROBARTY LATE ANIL KUMAR CHAKROBAR 3 2 5 7 7 ASHUTOSH COLONY 40 ASHUTOSH COLONY AJIT DAS JIBAN CH DAS 3 1 4 8 8 NELI NAGAR 2/157 NELI NAGAR AJIT MANDAL LT RADHA RAMAN MANDAL 3 2 5 9 9 K.P. ROY LANE 10A K.P. ROY LANE AJIT SARKAR LATE MAKHAN LAL SARKAR 2 1 3 10 10 GARFA VAIDYA PARA GARFA VAIDYA PARA ALOK BAIDYA LATE AJIT BAIDYA 3 1 4 11 11 SHAHID NAGAR 8/10 SHAHID NAGAR ALOK CHOUDHURY LT ACHALANANDA CHOUDHURY 1 1 2 12 12 JADAVGARH 3/65 JADAVGARH ALPANA SIKDAR LATE ASIT SIKDAR 2 1 3 13 13 NELI NAGAR 4/44 NELI NAGAR AMAL SHIL SURENDRA NATH SHIL 3 2 5 15 14 ASHUTOSH COLONY 13 ASHUTOSH COLONY AMAR DAS HAREN CH DAS 2 2 4 16 15 JADAVGARH 3/17B JADAVGARH AMIRON MONDAL IMON MONDAL 0 3 3 17 16 JADAVGARH 3/31 JADAVGARH AMIYA PAUL LATE KALACHAND PAUL 6 6 10+ 18 17 HALTU 11 HALTU MAIN ROAD ANIL DAS SUREN CH DAS 2 3 5 19 18 NELI NAGAR 2/159 NELI NAGAR ANIL DAS 3 1 4 20 19 ASHUTOSH COLONY 44A ASHUTOSH COLONY ANIL DAS MEKHU CH DAS 1 1 2 21 20 RAM KRISHNA PALLY 37 RAM KRISHNA PALLY ANIL MANDAL NARAYAN CH MANDAL 2 1 3 23 21 HALTU 3/56 JADAVGARH ANIL SARKAR LT MAKHAN LAL SARKAR 3 4 7 24 22 SHAHID NAGAR 8/34 SHAHID NAGAR ANIL SHAW 2 2 4 25 23 ASHUTOSH COLONY 91 ASHUTOSH COLONY ANITA DAS GURUDAS DAS 1 3 4 26 24 NELI NAGAR 1/18 NELI NAGAR ANITA MISTRI RAMESH MISTRI 1 1 2 27 25 DHAKURIA EAST ROAD 25/3 DHAKURIA EAST ROAD ANITA PAUL LATE BIMAL PAUL 2 1 3 28 26 SAHID NAGAR 8/2 SAHID NAGAR ANIYA BALA BASU LT BHUPENDRA KR. -

List of Members of the Zonal Railway Users’ Consultative Committee Eastern Railway for the Term 2011-13

LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE ZONAL RAILWAY USERS’ CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE EASTERN RAILWAY FOR THE TERM 2011-13 Sl. Name and Address Category Organisation No. 1 Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) Uttarpara, Digberia, Madhyamgram, Barasat, West Bengal. Ph - (033)- 25262959 (Telefax) Delhi Address :- 127, North Avenue, New Delhi - 110 001. 2 Smt. Satabdi Roy, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) 85, Prince Anwar Shah Road, City High Complex Flat -12 G, Kolkata-700 033. Ph - (03324) 227017, 09433025125(M) Delhi Address :- 33, North Avenue, New Delhi-110 001. Ph - 9013180070 (M) 3 Dr. Tarun Mandal, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) 22/1/3, Lakshi Narayan Tala Road, Botanical Gardens, Howrah - 711 103, West Bengal. Ph - (033) 26684184, 26687597, 9434097888 (M) Fax. (033) 26685451. Delhi Address :- 72, North Avenue, New Delhi - 110 001. Ph - 23093658, 9013180170 (M), Fax. (011) 23093698. 4 Shri Abu Hasem Khan Choudhury, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) Vill + P.O - Kotwali, Distt.-Malda, West Bengal. Ph - (03512)- 283593 Delhi Address :- C 1/6, Tilak Lane, New Delhi - 110 001. Ph - (011) 23782066, 9868180995 (M) Fax. (011) 23782065 5 Smt. Mausam Noor, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) (i) Vill & Post-Kotwali, P.S.-English Bazar, Distt.- Malda-732144 (West Bengal). (ii) 'Noor Mansion', Rathlari Station Road, Malda, West Bengal. Ph-(03512)-264560, 09830448612 (M) Delhi Address :- 80, South Avenue, New Delhi - 110 011. -

3 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for Sale in Santoshpur, Kolkata

https://www.propertywala.com/P73526590 Home » Kolkata Properties » Residential properties for sale in Kolkata » Apartments / Flats for sale in Santoshpur, Kolkata » Property P73526590 3 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for sale in Santoshpur, Kolkata 67 lakhs Apartment In Prudential Legend Advertiser Details Prudential Legend, Santoshpur, Kolkata - 700066 (West B… Area: 113.06 SqMeters ▾ Bedrooms: Three Bathrooms: Two Transaction: Resale Property Price: 6,700,000 Rate: 59,261 per SqMeter Possession: Immediate/Ready to move Description Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile Residential apartment is available for sell. It has good design of 3 bedrooms. Non-Stop water supply in 2 bathrooms. It has been furnishing. Situated in santoshpur. Area of the construction is 1217 sq.Ft.(Builtup Pictures area) . It has been priced at 'sixty three lakh rupees'. Located on 3rd floor of 4 total floors. Construction ages only new . Property is ready for possession . Property has amenities like water storage,Intercom facility,Security personnel,Lift(S),Visitor parking . It is newly constructed. Near to middle road, Kali temple Additional Details : is it a new builder floor or an old builder floor ? -- New builder is there stilt parking ? -- Yes is the floor area the covered area or super built up or floor area ? -- Super built up will i have a separate electricity and water connection and meter ? -- Electricity, will i have a separate underground tank or is it shared ? -- Shared is the overhead tank shared or seperate ? -- Shared is it on the main road or is it inside ? -- Main road When you call, please mention that you saw this ad on PropertyWala. -

Estate Directorate

ESTATE DIRECTORATE GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL New Secretariat Building, 9th Floor List of Applicants 01/09/14 Name of Estate ANY WHERE Estate Type SL Application No Name of Applicant Father/Husband's name Remarks NO Date Occupation Address Monthly/Annual Income Government Resident Special Reason Total Family Meb 1 01880 KALI PADA SARKAR LATE B. SARKAR SERVICE STATION RD. SIBMANDIR LANE 08/08/70 6,762.00 BANGAON-743235 ALLOTTED AT S.M.NAGAR PH-II LIG 4 24 PARGANAS (NORTH) N 2 00495 INDRA KUMAR KARMAKER SERVICE 10/H/14, SOUTH SEALDAH ROAD 25/03/75 4,000.00 CAL-15 ALLOTTED AT S.M.NAGAR PH-II LIG 5 N 3 03174 KALI KINKAR BATABYAL LATE GANESH CHANDRA BATABYAL SERVICE 17A, Indra Biswas Road 27/05/76 10,868.00 Cal.37 ALLOTTED AT S.M.NAGAR PH-II LIG 5 N 4 01881 DILIP KR. DAS LATE PRASANNA KR. DAS RETIRED 36A/1 FAKIR PARA RD. 16/05/77 2,303.00 BEHALA ALLOTTED F/N. Q/2 AT C N ROY RD IHE 4 CALCUTTA- 700 034 N 5 00336 BANSHI BADAN KABIRAJ SERVICE 17,CHANDRANATH SIMLAI LANE, 02/12/78 900.00 PAIKPARA, ALLOTTED AT S.M.NAGAR PH-II LIG 4 CAL-2. N 6 00684 PRIYA RANJAN BANERJEE SERVICE 73/20, BRUI PARA LANE 28/03/79 81.00 CAL-35 ALLOTTED AT S.M.NAGAR PH-II LIG 3 N Page 1 SL Application No Name of Applicant Father/Husband's name Remarks NO Date Occupation Address Monthly/Annual Income Government Resident Special Reason Total Family Meb 7 00542 ASHUTOSH MAITY SERVICE 287,CIRCULAR ROAD, 21/07/79 5,911.00 CHATTERJEEHAT,SHIBPUR, ALLOTTED AT S.M.NAGAR PH-II LIG 6 HOWRAH-2. -

Market Photos 1 - 15 a B - a C MARKET

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL AGRICULTURAL MARKET DIRECTORY MARKET SURVEY REPORT YEAR : 2011-2012 DISTRICT : KOLKATA THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING P-16, INDIA EXCHANGE PLACE EXTN. CIT BUILDING, 4 T H F L O O R KOLKATA-700073 THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING Government of West Bengal LIST OF MARKETS Kolkata District Sl. No. Name of Markets Block/Municipality Page No. 1 A B - A C Market K M C 1 2 A E Market - do - 2 3 Ahiritola Bazar - do - 3 4 Akhra Fatak Bazar - do - 4 5 Allah Bharosha Bazar - do - 5 6 Amiya Babur Bazar - do - 6 7 Anath Nath Deb Bazar - do - 7 8 Ashu Babur Bazar - do - 8 9 Azadgarh Bastuhara Samity Bazar - do - 9 10 B. K. Pal ( Hat Khola Bazar) - do - 10 11 B. N. R. Daily Market - do - 11 12 Babu Bazar Market - do - 12 13 Babur Bazar - do - 13 14 Badartala Bazar - do - 14 15 Bagbazar Market - do - 15 16 Bagha Jatin Bazar - do - 16 17 Bagmari Bazar - do - 17 18 Baithak Khana Bazar - do - 18 19 Bakultala Bazar - do - 19 20 Ballygunge Station Bazar - do - 20 21 Bantala Natun Bazar - do - 21 22 Bantala Natun Bazar Hat - do - 22 23 Barisha Super Market - do - 23 24 Bartala Bazar - do - 24 25 Basdroni Bazar - do - 25 26 Bastu Hara Bazar - do - 26 27 Behala Laxmi Puratan Bazar - do - 27 28 Behala Natun Bazar - do - 28 29 Belgachia Bazar - do - 29 30 Bengali Bazar - do - 30 31 Bibi Bazar - do - 31 32 Bijoygarh Bazar - do - 32 33 Bowbazar Chhana Patty - do - 33 34 Bowbazar Market - do - 34 35 Burman Market - do - 35 36 Buro Shibtala Bazar - do - 36 37 Charu Market Bazar - do - 37 38 Chetla Bazar - do - 38 39 Chetla K. -

Disaster Management

ACTION PLAN TO MITIGATE FLOOD, CYCLONE & WATER LOGGING 2017 THE KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 1 2 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INCLUDING ACTION PLANS ARE MENTIONED UNDER FOLLOWING HEADS Sl No Item Page A Disaster Management – Introduction 5 B Important Activities of KMC in 11 connection with the Disaster Management C Major Water Logging Pockets 15 D Deployment of KMC Mazdoor at Major 29 Water Logging Pockets E Arrangement all Parks & Square 39 Development required removal of uprooting trees trimining at trees F List of the Sewerage and Drainage 45 Pumping Stations and deployment of temporary portable pumps during monsoon G Emergency arrangement during the 77 ensuing Nor’wester/Rainy season in the next few months of 2017 (Mpl. Commr. Circular No 11 of 2017-18 Dated 06/05/2017) H List of the roads where cleaning of G. 97 Ps. mouths /sweeping of roads will be made twice in a day by S.W.M. Department I Essential Telephone Numbers 107 3 4 A. DISASTER MANAGEMENT – INTRODUCTION The total area under Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) is about 204.75 Sq. Km. which is divided into 16 Boroughs from Ward No-1 to Ward No- 144. The total population of the KMC area as per 2001 Census is about 4.6 million. Moreover, the floating population of the city is about 6 million. They are coming to this city for their livelihood from the outskirt and suburbs of the city of Kolkata i.e. City of Joy. From the experience regarding the water logging/flood condition during rainy season for the last few years, the KMC authority felt to publicize the disaster management plan as well as disaster management system for the benefit of the citizens, local representatives, State Govt. -

2 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for Rent in Picnic Garden Roads, Kolkata

https://www.propertywala.com/P38284103 Home » Kolkata Properties » Residential properties for rent in Kolkata » Apartments / Flats for rent in Picnic Garden Roads, Kolkata » Property P38284103 2 Bedroom Apartment / Flat for rent in Picnic Garden Roads, Kolkata 12,000 Flat For Rent In Picnic Garden Kasba Kolkata Advertiser Details Picnic Garden Road, Picnic Garden Roads, Kolkata - 7000… Area: 1050 SqFeet ▾ Bedrooms: Two Bathrooms: Two Floor: First Total Floors: Four Facing: East Furnished: Semi Furnished Lease Period: 11 Months Monthly Rent: 12,000 Rate: 11 per SqFeet -30% Age Of Construction: 2 Years Available: Immediate/Ready to move Scan QR code to get the contact info on your mobile View all properties by Houseaa Reality Description Good looking flat for rent near Picnic Garden connected to be Raspberry connector and EM Bypass near Pictures Bazar hospitals college available Please mention that you saw this ad on PropertyWala.com when you call. Features Lot Interior Bedroom Kitchen Balcony Marble Flooring Maintenance Water Supply / Storage Waste Disposal Location Bedroom Bathroom * Location may be approximate Landmarks Education The Academy (<4km), IKON (<10km), South Point High School (<1km), St. Joseph, Jagadbandhu Institution (<2km), La Martiniere for Girls (<4km), St. James, Loreto Convent Entally (<5km), SIP Abacus Parkcircus (<4km), Lakshmipat Singhania Academy (<7k…Jack and Jill (<3km), South City International School (<5k… Abacus Brain Gym (<5km), PLUTO - Play School Day Care & Act… Sishu Bharati School (<12km), National Stores -

16‐06‐20 13 5 Seals Garden Lane Cossipore 700002 1 1

Affected Zone DAYS SINCE Date of reporting of REPORTING Sl No. Address Ward Borough Local area the case 13 5 SEALS GARDEN LANE The premises itself 1 1 1 Cossipore 16‐06‐20 COSSIPORE 700002 14 The affected flat/the 59 Kalicharan Ghosh Rd standalone house 2 kolkata ‐ 700050 West 2 1 Sinthi Bengal India 16‐06‐20 14 The premises itself 21/123 RAJA MANINDRA 3 31 Paikpara ROAD BELGACHIA 700037 16‐06‐20 14 14A BIRPARA LANE The premises itself 4 kolkata ‐ 700030 West 31 Belgachia 16‐06 ‐20 BBlIdiengal India 14 The flat itself A4 6 R D B RD Kolkata ‐ 5 41 Paikpara 700002 West Bengal India 16‐06‐20 14 110/1A COSSIPORE Road The premises itself 6 Kolkata ‐ 700002 West 6 1 Chitpur 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 Adjacent common passage of affected hut 14 3 GALIFF STREET 7 7 1 Bagbazar including toilet and BAGHBAZAR 700003 water source of the 16‐06‐20 slum 14 Adjacent common passage of affected hut 14 3 GALIFF STREET 8 7 1 Bagbazar including toilet and BAGHBAZAR 700003 water source of the 16‐06‐20 slum 14 Affected Zone DAYS SINCE Date of reporting of REPORTING Sl No. Address Ward Borough Local area the case 1 RAMKRISHNA LANE The premises itself 9 Kolkata ‐ 700003 West 7 1 Girish Mancha 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 The premises itself 4/2/1B KRISHNA RAM BOSE 10 STREET SHYAMPUKUR 10 2 Shyampukur KOLKATA 700004 16‐06‐20 14 T/1D Guru Charan Lane The premises itself 11 Kolkata ‐ 700004 West 10 2 Hatibagan 16‐06‐20 Bengal India 14 Adjacent common 47 1 SHYAMBAZAR STREET passage of affected hut 12 Kolk at a ‐ 700004 W est 10 2 Shyampu kur iilditiltdncluding toilet and -

List of BPL Households: ULB Name : KOLKATA MC ULB Code : 79 Sl

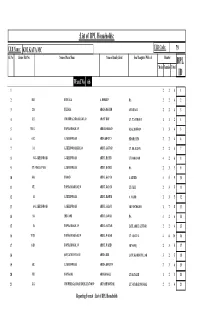

:List of BPL Households: ULB Name : KOLKATA MC ULB Code : 79 Sl. No House/ Flat No. Name of Para/ Slum Name of family Head Son/ Daughter/ Wife of Member BPL Male Female Total ID Ward No 66 1 2 2 4 1 2 H/D BANTALA A. HOSSEIN NA 2 2 4 2 3 22A TILJALA ABADA BAGAM AMAIR ALI 2 2 4 3 4 12/2 CHOUBHAGA ROAD, KOL-39 ABANY ROY LT. T.NATH ROY 1 1 2 4 5 35/1G TOPSIA RD KOL 39 ABBAS HOSSAIN AZAZ HOSSAIN 1 3 4 5 6 60/2 G J KHAN ROAD ABDA KHATUN MD SHAMIM 2 2 4 6 7 3/1 G.J.KHAN ROAD,KOL-39 ABDUL GAFFAR LT. SK.ALIJAN 2 2 4 7 8 50 G.J.KHAN ROAD G.J.KHAN ROAD ABDUL HAMID LT RAHAMAN 4 2 6 8 9 47Y MOLLA PARA G J KHAN ROAD ABDUL KADER NA 2 3 5 9 10 84A T ROAD ABDUL KALAM A AHMED 4 5 9 10 11 47E TOPSIA ROAD KOL 39 ABDUL KALAM LT JALIL 2 3 5 11 12 44 G J KHAN ROAD ABDUL RASHID A. MAJID 2 3 5 12 13 63 G.J.KHAN ROAD G.J.KHAN ROAD ABDUL SALAM SK PANCHKORI 1 7 8 13 14 8A 2ND LANE ABDUL SAMAD NA 4 2 6 14 15 36 TOPSIA RD KOL 39 ABDUL SATTAR LATE ABDUL GUFFOR 2 2 4 15 16 73/7B TOPSIA ROAD KOL 39 ABDUL WAHAB LT A SALLAI 4 6 10 16 17 8/1B TOPSIA RD KOL 39 ABDUL WAHID SK NASIQ 2 3 5 17 18 SAPGACHI 1ST LANE ABEDA BIBI LATE SK HIDUTULLAH 3 2 5 18 19 41E G J KHAN ROAD ABEDA KHATUN 3 3 6 19 20 47D TOPSIA RD ABID SHAKEL LT SK TALIB 1 2 3 20 21 12/2 CHOWBHAGA ROAD KOLKATA-700039 ABINASH MONDAL LT NATABAR MONDAL 2 2 4 21 Reporting Format : List of BPL Households :List of BPL Households: ULB Name : KOLKATA MC ULB Code : 79 Sl. -

Indian Leather Products Association Member List Sl

INDIAN LEATHER PRODUCTS ASSOCIATION MEMBER LIST SL.NO MEMBER DETAILS EMAIL ID 1 Asian Leather Private Limited [email protected] “ASIAN HOUSE” E.M. Bypass, Kasba Kolkata - 700 107 2 Anjana Exports Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] ,[email protected] , 23A, Netaji Subhas Road [email protected] 2nd Floor, Suite No. 2 Kolkata - 700 001 3 Ahmed Tannery Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] , [email protected] 10/1/1A, Topsia Road (South) Kolkata - 700 046 4 AKE Exporter Private Limited [email protected] , [email protected] Kasba Industrial Estate Phase - 1, Plot - 3 Kolkata - 700 107 5 ASG Leather Private Limited [email protected] , aloke_asgleather.com; , 30B/2, Gulam Jilani Khan Road [email protected] Kolkata - 700 039 6 Acknit Industries Limited [email protected] , [email protected] 817, ‘KRISHNA BUILDING’ 224, A.J.C. Bose Road Kolkata - 700 017 7 Acme Leathercraft [email protected] 294/1 (2nd Floor), Chattarpur Pahari (Behind MTNL office) Chattarpur New Delhi - 110 074 8 Alliance International [email protected] , 24, Girish Chandra Bose Road [email protected] (Near S.B.I. Entally Market) Kolkata - 700 014 9 Balaji Export Corpn. [email protected] , [email protected], P-66, Kasba Industrial Estate [email protected] Phase - II Kolkata - 700 107 10 B.S. Arora & Sons HUF [email protected] 11, Short Street Kolkata - 700 016 11 Balaji Leather Creation [email protected] Udayan Industrial Estate 3 No. Pagladanga Main Road Plot No. 49 & 52 Kolkata - 700 015 12 Banbros Exports Pvt. Ltd. [email protected] 64/1, K.K.