The Trombone and Bass Trumpet in Modern Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music

1 Kristen Masada and Razvan Bunescu: A Segmental CRF Model for Chord Recognition in Symbolic Music A. Types of Chords in Tonal Music minished triads most frequently contain a diminished A chord is a group of notes that form a cohesive har- seventh interval (9 half steps), producing a fully di- monic unit to the listener when sounding simulta- minished seventh chord, or a minor seventh interval, neously (Aldwell et al., 2011). We design our sys- creating a half-diminished seventh chord. tem to handle the following types of chords: triads, augmented 6th chords, suspended chords, and power A.2 Augmented 6th Chords chords. An augmented 6th chord is a type of chromatic chord defined by an augmented sixth interval between the A.1 Triads lowest and highest notes of the chord (Aldwell et al., A triad is the prototypical instance of a chord. It is 2011). The three most common types of augmented based on a root note, which forms the lowest note of a 6th chords are Italian, German, and French sixth chord in standard position. A third and a fifth are then chords, as shown in Figure 8 in the key of A minor. built on top of this root to create a three-note chord. In- In a minor scale, Italian sixth chords can be seen as verted triads also exist, where the third or fifth instead iv chords with a sharpened root, in the first inversion. appears as the lowest note. The chord labels used in Thus, they can be created by stacking the sixth, first, our system do not distinguish among inversions of the and sharpened fourth scale degrees. -

Year 11 Music Revision Guide

Year 11 Music Revision Guidance Name the musical instrument In the exam you will be asked to name different instruments that you can hear playing. If you do not play one of these instruments it can sometimes be quite difficult to pick out what each one sounds like. You will need to know what the different instruments of the orchestra sound like, what popular musical instruments sound like and what some world instruments sound like (sitar). It is worth you visiting www.dsokids.com or www.compositionlab.co.uk where you will be able to hear these instruments individually. Describing musical sounds For some questions in the exam you will need to describe what is happening in the music, in detail! If you are asked to comment on what is happening in the music you may need to describe what a particular instrument is doing, for example: ‘The left hand of the piano is playing ascending arpeggios’. The more detail you can provide, the better! Melodic movement You may be asked to describe what is happening in the melody of a song. Remember, this means the main tune. In popular music this is often the vocal line or in instrumental music it can be described as the instrument that has the main tune (the bit that you could whistle). It could move by STEP; this means it moves to the note next to it. It could move by LEAP; this means that the melody jumps from one note to another but misses some notes out in between. This could be a low note jumping to a high note or vice versa. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Figured-Bass.Pdf

Basic Theory Quick Reference: Figured Bass Figured bass was developed in the Baroque period as a practical short hand to help continuo players harmonise a bass line at sight. The basic principle is very easy: each number simply denotes an interval above the bass note The only complication is that not every note of every chord needed is given a figure. Instead a convention developed of writing the minimum number of figures needed to work out the harmony for each bass note. The continuo player presumes that the bass note is the root of the chord unless the figures indicate otherwise. The example below shows the figuring for common chords - figures that are usually omitted are shown in brackets: Accidentals Where needed, these are placed after the relevant number. Figures are treated exactly the same as notes on the stave. In the example below the F# does not need an accidental, because it is in the key signature. On the other hand, the C# does to be shown because it is not in the key signature. An accidental on its own always refers to the third above the bass note. 33 For analytical purposes we will combine Roman Numerals (i.e. I or V) with figured bass to show the inversion. Cadential 6/4 Second inversion chords are unstable and in the Western Classical Tradition they tend to resolve rather than stand as a proper chord on their own. In the example below, the 6/4 above the G could be described as a C chord in second inversion. In reality, though, it resolves onto the G chord that follows and can better be understood as a decoration (double appoggiatura) onto this chord. -

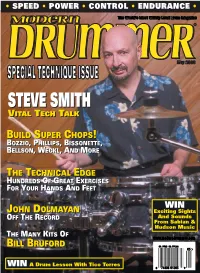

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades. -

Figured-Bass Notation

MU 182: Theory II R. Vigil FIGURED-BASS NOTATION General In common-practice tonal music, chords are generally understood in two different ways. On the one hand, they can be seen as triadic structures emanating from a generative root . In this system, a root-position triad is understood as the "ideal" or "original" form, and other forms are understood as inversions , where the root has been placed above one of the other chord tones. This approach emphasizes the structural similarity of chords that share a common root (a first- inversion C major triad and a root-position C major triad are both C major triads). This type of thinking is represented analytically in the practice of applying Roman numerals to various chords within a given key - all chords with allegiance to the same Roman numeral are understood to be related, regardless of inversion and voicing, texture, etc. On the other hand, chords can be understood as vertical arrangements of tones above a given bass . This system is not based on a judgment as to the primacy of any particular chordal arrangement over another. Rather, it is simply a descriptive mechanism, for identifying what notes are present in addition to the bass. In this regime, chords are described in terms of the simplest possible arrangement of those notes as intervals above the bass. The intervals are represented as Arabic numerals (figures), and the resulting nomenclatural system is known as figured bass . Terminological Distinctions Between Roman Numeral Versus Figured Bass Approaches When dealing with Roman numerals, everything is understood in relation to the root; therefore, the components of a triad are the root, the third, and the fifth. -

Teaching Tuba Students to Be Complete Musicians Brandon E

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2017 Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians Brandon E. Cummings [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Educational Methods Commons, Music Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Brandon E., "Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians" (2017). Honors Research Projects. 577. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/577 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Running head: TEACHING TUBA STUDENTS TO BE COMPLETE MUSICIANS 1 Teaching Tuba Students to be Complete Musicians Brandon E. Cummings The University of Akron TEACHING TUBA STUDENTS TO BE COMPLETE MUSICIANS 2 Abstract The goal of music educators is to develop complete musicians who successfully learn and perform all musical concepts. One of the limitations of the band classroom is that performers are required to play a part that is specifically written with the needs of the ensemble in mind, and not the needs of the developing musician. -

Intro Pdf. Version

Vertical Harmony Concepts The purpose of this book is to familiarize the bassist with chord structures and to enhance his ability to solo intelligently and effectively. While many of these concepts can be applied to bass lines and fills, these exercises will focus more on soloing. The words "horn-like" are often used to describe solos that are fluid and graceful. To achieve this type of description, one needs to listen to, practice, transcribe and ultimately understand what a soloist is playing. The first step to understanding is knowing chord structures. As bassists, we typically aren't called upon to play chords. So why even know them? That is the question I get from many of my beginning students. Or, "just tell me the root, I'll figure it out from there" which usually means "I'll plod along on the root." We bassists are not only responsible for holding things together rhythmically; we are also the keepers of the harmony. If you don't understand how chords are constructed, how are you going to hold things together? Let alone solo? Playing root notes will only get you so far. Fortunately, knowing what it takes to construct a chord is easy, and by knowing the construction (quality), you should never play a "wrong" note. Intervals are what make up any type of musical structure. Everything you play will involve intervals. An understanding of intervals is essential for understanding music. An interval is the distance between two notes. In Western music there are twelve intervals. Each interval has a numerical identity. -

BAM R&B Festival at Metrotech Returns with 10 Free Concerts, Jun 7

BAM R&B Festival at MetroTech returns with 10 free concerts, Jun 7—Aug 9 The stellar lineup includes Bernard Purdie, Bobbi Humphrey, Savion Glover, Terence Blanchard, Vivian Green, and Marcus Miller Forest City Ratner Companies is the Presenting Sponsor of BAM R&B Festival at MetroTech BAM R&B Festival at MetroTech Thursdays, noon—2pm, Jun 7—Aug 9 Free admission, MetroTech Commons at MetroTech Center Produced by Danny Kapilian Jun 7 Bernard Purdie’s All-Star Shuffle with guests Bobbi Humphrey and Quiana Lynell Jun 14 Savion Glover featuring Marcus Gilmore Jun 21 PJ Morton Jun 28 Vivian Green Jul 5 Delgres Jul 12 Amalgarhythm with Kris Davis and Terri Lyne Carrington Jul 19 Jupiter & Okwess Jul 26 Terence Blanchard featuring the E-Collective Aug 2 Ranky Tanky Aug 9 Marcus Miller May 3, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—BAM R&B Festival at MetroTech, Downtown Brooklyn’s best summer tradition, returns from June 7 to August 9 with 10 afternoons of jazz, soul, R&B, and some tap dancing. Now in its 24th year, the festival continues to feature music legends alongside groundbreaking emerging artists. Producer Danny Kapilian said, “It’s so great to bring dynamic artists every year to perform in Downtown Brooklyn. This is one of those adventurous years where we are stepping into some thrilling new musical territory. Four of our star artists this summer live where R&B and jazz combine to create something totally new. Legendary tap dancing star Savion Glover presents a duo performance with the brilliant young jazz drummer Marcus Gilmore. Terri Lyne Carrington is a three-time Grammy-winning drummer who’s bridged the music of Dianne Reeves, Esperanza Spalding, and Valerie Simpson. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Automatic Transcription of Bass Guitar Tracks Applied for Music Genre Classification and Sound Synthesis

Automatic Transcription of Bass Guitar Tracks applied for Music Genre Classification and Sound Synthesis Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktoringenieur (Dr.-Ing.) vorlelegt der Fakultät für Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Technischen Universität Ilmenau von Dipl.-Ing. Jakob Abeßer geboren am 3. Mai 1983 in Jena Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gerald Schuller Prof. Dr. Meinard Müller Dr. Tech. Anssi Klapuri Tag der Einreichung: 05.12.2013 Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 18.09.2014 urn:nbn:de:gbv:ilm1-2014000294 ii Acknowledgments I am grateful to many people who supported me in the last five years during the preparation of this thesis. First of all, I would like to thank Prof. Dr.-Ing. Gerald Schuller for being my supervisor and for the inspiring discussions that improved my understanding of good scientific practice. My gratitude also goes to Prof. Dr. Meinard Müller and Dr. Anssi Klapuri for being available as reviewers. Thank you for the valuable comments that helped me to improve my thesis. I would like to thank my former and current colleagues and fellow PhD students at the Semantic Music Technologies Group at the Fraunhofer IDMT for the very pleasant and motivating working atmosphere. Thank you Christian, Holger, Sascha, Hanna, Patrick, Christof, Daniel, Anna, and especially Alex and Estefanía for all the tea-time conversations, discussions, last-minute proof readings, and assistance of any kind. Thank you Paul for providing your musicological expertise and perspective in the genre classification experiments. I also thank Prof. Petri Toiviainen, Dr. Olivier Lartillot, and all the collegues at the Finnish Centre of Excellence in Interdisciplinary Music Research at the University of Jyväskylä for a very inspiring research stay in 2010. -

Intro to Figured Bass

Introduction to Figured Bass Figured bass symbols describe the vertical structure of the chord! The bass is the foundation of harmonic structure. Figured bass symbols are used to indicate the bass positions of chords. The practice is derived from Baroque keyboard music where the player read from a part consisting of a bass line and some numerical symbols that indicated what chord was to be played. It was shorthand and, consequently, allowed an element of improvisation to enter the performance. The figured bass symbols represent intervals above the bass. The notes obtained by these intervals may be played in any octave. The figured bass does not indicate open or closed spacing. The system deals only with intervals (During its period of invention, the theory of chords was not yet invented). Figured bass was used as a means to notate improvisations, teach composition, and was the fundamental means by which composers such as Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven learned their craft. The following example illustrates the figured bass symbols for triads and their inversions only. Ex. 1 (a) (b) (c) 5 6 6 3 3 4 (root position) (1st inversion) (2nd inversion) The numbers in the above example represent the "general interval" from the lowest note in each chord to each upper note. The general interval, as you may recall, is simply the number of letter names from one pitch to another (remember to count the starting pitch as 1). In (a), C-E is a 3rd, C-G is a 5th, hence the 5/3 figured bass symbol. It is important to know that each figured bass number represents an interval above the bass.