Who Is Afraid of Neoliberalism? a Comment on Mirowski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Austrian School in Bulgaria: a History✩ Nikolay Nenovsky A,*, Pencho Penchev B

Russian Journal of Economics 4 (2018) 44–64 DOI 10.3897/j.ruje.4.26005 Publication date: 23 April 2018 www.rujec.org The Austrian school in Bulgaria: A history✩ Nikolay Nenovsky a,*, Pencho Penchev b a University of Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens, France b University of National and World Economy, Sofia, Bulgaria Abstract The main goal of this study is to highlight the acceptance, dissemination, interpretation, criticism and make some attempts at contributing to Austrian economics made in Bulgaria during the last 120 years. We consider some of the main characteristics of the Austrian school, such as subjectivism and marginalism, as basic components of the economic thought in Bulgaria and as incentives for the development of some original theoreti- cal contributions. Even during the first few years of Communist regime (1944–1989), with its Marxist monopoly over intellectual life, the Austrian school had some impact on the economic thought in the country. Subsequent to the collapse of Communism, there was a sort of a Renaissance and rediscovery of this school. Another contribution of our study is that it illustrates the adaptability and spontaneous evolution of ideas in a different and sometimes hostile environment. Keywords: history of economic thought, dissemination of economic ideas, Austrian school, Bulgaria. JEL classification: B00, B13, B30, B41. 1. Introduction The emergence and development of specialized economic thought amongst the Bulgarian intellectuals was a process that occurred significantly slowly in comparison to Western and Central Europe. It also had its specific fea- tures. The first of these was that almost until the outset of the 20th century, the economic theories and different concepts related to them were not well known. -

Liam Brunt – Teaching Material – Keynesian Revolution 1 Week 4

Liam Brunt – Teaching Material – Keynesian Revolution Week 4. The Keynesian Revolution. What were the major theoretical and practical obstacles to the adoption of Keynesian demand management to cure unemployment in the inter-war years? Would it have been effective? Was there a ‘Keynesian Revolution’ in economic thought and policy in the 1940s and 1950s? Readings. Peden, G. C., ‘The “Treasury View” on Public Works and Employment in the Inter-war Period,’ Economic History Review (1984). Outlines the theoretical orthodoxy against which Keynes rebelled. Middleton, R. C., ‘The Treasury in the 1930s: Political and Administrative Constraints to the Acceptance of the “New” Economics,’ Oxford Economic Papers (1982). McKibbin, R. I., ‘The Economic Policy of the Second Labour Government, 1929-31,’ Past and Present (1975). [Number 68, p96-102]. A useful look at the international reception of Keynesian policies. Floud, R., and D. N. McCloskey, The Economic History of Britain since 1700, vol. 2 (1860-1939). (Second edition, 1994). [Chapter 14 (Thomas)]. Quantitative analysis of the impact of plausible Keynesian policies. Booth, A. R., ‘The “Keynesian Revolution” in Economic Policy-making,’ Economic History Review (1983). See also the comment by Tomlinson, Economic History Review (1984). Discusses the definition and timing of the Keynesian revolution. Rollings, N., ‘British Budgetary Policy, 1945-54: a “Keynesian Revolution”?’ Economic History Review (1988). A strong rebuttal of Booth. Note: if you are unsure about the Keynesian model of the labour market then refer to Levacic and Rebmann, p70-5, 86-93. 1 Liam Brunt – Teaching Material – Keynesian Revolution KEYNESIANISM. The Central Features Of Keynesianism. 1. The economy was not self-adjusting and the government should use active policy to bring the economy back to full employment in a recession. -

Meet the 2020 Chinese Consumer

McKinsey Consumer & Shopper Insights Meet the 2020 Chinese Consumer McKinsey Insights China McKinsey Consumer & Shopper Insights March 2012 Meet the 2020 Chinese Consumer Yuval Atsmon Max Magni Lihua Li Wenkan Liao The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of their colleagues: Molly Liu, Cherie Zhang, Barry Liu, Rachel Zheng, Justin Peng, William Cheng, Glenn Leibowitz, Joanne Mason. 5 Contents Introduction 6 1. China at a turning point 8 2. Getting the basics right: changing demographics 12 Mainstream consumers driving income growth 13 Aging population 17 Postponed life stages 18 Increasingly independent women 18 3. Understanding the mainstream consumer: new spending patterns 20 Growing discretionary spending 21 Aspirations-driven trading up 22 Emerging senior market 23 Evolving geographic differences 24 4. Understanding the mainstream consumer: behavioral patterns 26 The still-pragmatic consumer 27 The individual consumer 27 The increasingly loyal consumer 28 The modern shopper 29 5. Preparing for the 2020 consumer: implications for companies 34 Strategic imperatives 35 Growth enablers 37 Conclusion 37 Introduction Meet the 2020 Chinese consumer 7 Most large, consumer-facing companies have long realized that they will need China’s growth to power their own in the next decade. But to keep pace, they will also need to understand the economic, societal, and demographic changes that are shaping consumers’ profiles and the way they spend. This is no easy task, not only because of the fast pace of growth and subsequent changes being wrought on the Chinese way of life, but also because there are vast economic and demographic differences across China. These are set to become more marked, with significant implications for companies that fail to grasp them. -

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics

Lecture Notes1 Mathematical Ecnomics Guoqiang TIAN Department of Economics Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843 ([email protected]) This version: August, 2020 1The most materials of this lecture notes are drawn from Chiang’s classic textbook Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, which are used for my teaching and con- venience of my students in class. Please not distribute it to any others. Contents 1 The Nature of Mathematical Economics 1 1.1 Economics and Mathematical Economics . 1 1.2 Advantages of Mathematical Approach . 3 2 Economic Models 5 2.1 Ingredients of a Mathematical Model . 5 2.2 The Real-Number System . 5 2.3 The Concept of Sets . 6 2.4 Relations and Functions . 9 2.5 Types of Function . 11 2.6 Functions of Two or More Independent Variables . 12 2.7 Levels of Generality . 13 3 Equilibrium Analysis in Economics 15 3.1 The Meaning of Equilibrium . 15 3.2 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Linear Model . 16 3.3 Partial Market Equilibrium - A Nonlinear Model . 18 3.4 General Market Equilibrium . 19 3.5 Equilibrium in National-Income Analysis . 23 4 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra 25 4.1 Matrix and Vectors . 26 i ii CONTENTS 4.2 Matrix Operations . 29 4.3 Linear Dependance of Vectors . 32 4.4 Commutative, Associative, and Distributive Laws . 33 4.5 Identity Matrices and Null Matrices . 34 4.6 Transposes and Inverses . 36 5 Linear Models and Matrix Algebra (Continued) 41 5.1 Conditions for Nonsingularity of a Matrix . 41 5.2 Test of Nonsingularity by Use of Determinant . -

Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Lima, Gerson P. Macroambiente 3 March 2015 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63135/ MPRA Paper No. 63135, posted 21 Mar 2015 13:54 UTC Supply and Demand Is Not a Neoclassical Concern Gerson P. Lima1 The present treatise is an attempt to present a modern version of old doctrines with the aid of the new work, and with reference to the new problems, of our own age (Marshall, 1890, Preface to the First Edition). 1. Introduction Many people are convinced that the contemporaneous mainstream economics is not qualified to explaining what is going on, to tame financial markets, to avoid crises and to provide a concrete solution to the poor and deteriorating situation of a large portion of the world population. Many economists, students, newspapers and informed people are asking for and expecting a new economics, a real world economic science. “The Keynes- inspired building-blocks are there. But it is admittedly a long way to go before the whole construction is in place. But the sooner we are intellectually honest and ready to admit that modern neoclassical macroeconomics and its microfoundationalist programme has come to way’s end – the sooner we can redirect our aspirations to more fruitful endeavours” (Syll, 2014, p. 28). Accordingly, this paper demonstrates that current mainstream monetarist economics cannot be science and proposes new approaches to economic theory and econometric method that after replication and enhancement may be a starting point for the creation of the real world economic theory. -

Cryptocurrency: the Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues

Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues Updated April 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45427 SUMMARY R45427 Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and April 9, 2020 Selected Policy Issues David W. Perkins Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require Specialist in government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, users of the Macroeconomic Policy system validate payments using certain protocols. Since the 2008 invention of the first cryptocurrency, Bitcoin, cryptocurrencies have proliferated. In recent years, they experienced a rapid increase and subsequent decrease in value. One estimate found that, as of March 2020, there were more than 5,100 different cryptocurrencies worth about $231 billion. Given this rapid growth and volatility, cryptocurrencies have drawn the attention of the public and policymakers. A particularly notable feature of cryptocurrencies is their potential to act as an alternative form of money. Historically, money has either had intrinsic value or derived value from government decree. Using money electronically generally has involved using the private ledgers and systems of at least one trusted intermediary. Cryptocurrencies, by contrast, generally employ user agreement, a network of users, and cryptographic protocols to achieve valid transfers of value. Cryptocurrency users typically use a pseudonymous address to identify each other and a passcode or private key to make changes to a public ledger in order to transfer value between accounts. Other computers in the network validate these transfers. Through this use of blockchain technology, cryptocurrency systems protect their public ledgers of accounts against manipulation, so that users can only send cryptocurrency to which they have access, thus allowing users to make valid transfers without a centralized, trusted intermediary. -

A Post-Keynesian Approach As an Alternative to Neoclassical in the Explanation of Monetary and Financial System

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zachariadis, Savvas Article A Post-Keynesian approach as an alternative to neoclassical in the explanation of monetary and financial system Financial Studies Provided in Cooperation with: "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), Romanian Academy Suggested Citation: Zachariadis, Savvas (2020) : A Post-Keynesian approach as an alternative to neoclassical in the explanation of monetary and financial system, Financial Studies, ISSN 2066-6071, Romanian Academy, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, Bucharest, Vol. 24, Iss. 1 (87), pp. 21-35 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231693 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

New Monetarist Economics: Methods∗

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research Department Staff Report 442 April 2010 New Monetarist Economics: Methods∗ Stephen Williamson Washington University in St. Louis and Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond and St. Louis Randall Wright University of Wisconsin — Madison and Federal Reserve Banks of Minneapolis and Philadelphia ABSTRACT This essay articulates the principles and practices of New Monetarism, our label for a recent body of work on money, banking, payments, and asset markets. We first discuss methodological issues distinguishing our approach from others: New Monetarism has something in common with Old Monetarism, but there are also important differences; it has little in common with Keynesianism. We describe the principles of these schools and contrast them with our approach. To show how it works, in practice, we build a benchmark New Monetarist model, and use it to study several issues, including the cost of inflation, liquidity and asset trading. We also develop a new model of banking. ∗We thank many friends and colleagues for useful discussions and comments, including Neil Wallace, Fernando Alvarez, Robert Lucas, Guillaume Rocheteau, and Lucy Liu. We thank the NSF for financial support. Wright also thanks for support the Ray Zemon Chair in Liquid Assets at the Wisconsin Business School. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis, or the Federal Reserve System. 1Introduction The purpose of this essay is to articulate the principles and practices of a school of thought we call New Monetarist Economics. It is a companion piece to Williamson and Wright (2010), which provides more of a survey of the models used in this literature, and focuses on technical issues to the neglect of methodology or history of thought. -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

Neoliberal Reason and Its Forms: Depoliticisation Through

Neoliberal Reason and Its Forms: De-Politicisation Through Economisation Yahya M. Madra and Fikret Adaman Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul, Turkey; [email protected] Abstract: This paper offers a historically contextualised intellectual history of the entangled development of three competing post-war economic approaches, viz the Austrian, Chicago and post-Walrasian schools, as three forms of neoliberalism. Taking our cue from Foucault’s reading of neoliberalism as a mode of governmentality under which the social is organised through “economic incentives”, we engage with the recent discussions of neoliberal theory on three accounts: neoliberalism is read as an epistemic horizon including not only “pro-” but also “post-market” positions articulated by post- Walrasian economists who claim that market failures necessitate the design of “incentive-compatible” remedial mechanisms; the Austrian tradition is distinguished from the Chicago-style pro-marketism; and the implications of the differences among the three approaches on economic as well as socio-political life are discussed. The paper maintains that all three approaches promote the de-politicisation of the social through its economisation albeit by way of different theories and policies. Keywords: Michel Foucault, economisation, Austrian School, Chicago School, post- Walrasian School Introduction More than half a decade after the 2008 Crash and with no end in sight to depressive economic conditions, neoliberal reason displays a certain resiliency. In time, the initial calls for intervention and regulation transformed into austerity programs run by technocratic governments. In the absence of a major redistribution of wealth and income, returning to a New Deal arrangement with well paying secure jobs for all, comprehensive social security, free and quality education, accessible healthcare and active government involvement in social welfare, appears to many a nostalgic indulgence. -

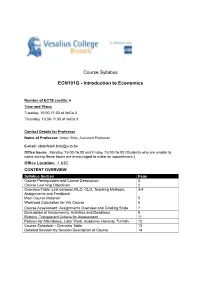

Course Syllabus ECN101G

Course Syllabus ECN101G - Introduction to Economics Number of ECTS credits: 6 Time and Place: Tuesday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Thursday, 10:00-11:30 at VeCo 3 Contact Details for Professor Name of Professor: Abdel. Bitat, Assistant Professor E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Monday, 15:00-16:00 and Friday, 15:00-16:00 (Students who are unable to come during these hours are encouraged to make an appointment.) Office Location: -1.63C CONTENT OVERVIEW Syllabus Section Page Course Prerequisites and Course Description 2 Course Learning Objectives 2 Overview Table: Link between MLO, CLO, Teaching Methods, 3-4 Assignments and Feedback Main Course Material 5 Workload Calculation for this Course 6 Course Assessment: Assignments Overview and Grading Scale 7 Description of Assignments, Activities and Deadlines 8 Rubrics: Transparent Criteria for Assessment 11 Policies for Attendance, Later Work, Academic Honesty, Turnitin 12 Course Schedule – Overview Table 13 Detailed Session-by-Session Description of Course 14 Course Prerequisites (if any) There are no pre-requisites for the course. However, since economics is mathematically intensive, it is worth reviewing secondary school mathematics for a good mastering of the course. A great source which starts with the basics and is available at the VUB library is Simon, C., & Blume, L. (1994). Mathematics for economists. New York: Norton. Course Description The course illustrates the way in which economists view the world. You will learn about basic tools of micro- and macroeconomic analysis and, by applying them, you will understand the behavior of households, firms and government. Problems include: trade and specialization; the operation of markets; industrial structure and economic welfare; the determination of aggregate output and price level; fiscal and monetary policy and foreign exchange rates. -

Preferences for Bipartisanship in the American Electorate Laurel

Compromise vs. Compromises: Preferences for Bipartisanship in the American Electorate Laurel Harbridge* Assistant Professor, Northwestern University Faculty Fellow, Institute for Policy Research [email protected] Scott Hall 601 University Place Evanston, IL 60208 (847) 467-1147 Neil Malhotra Associate Professor, Stanford Graduate School of Business [email protected] 655 Knight Way Stanford, CA 94035 (408) 772-7969 Brian F. Harrison PhD Candidate, Northwestern University [email protected] Scott Hall 601 University Place Evanston, IL 60208 * Corresponding author. We thank Time-Sharing Experiments in the Social Sciences (TESS) for providing the majority of the financial support of this project. TESS is funded by the National Science Foundation (SES- 0818839). A previous version of this paper was scheduled for presentation at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association. Abstract Public opinion surveys regularly assert that Americans want political leaders to work together and to engage in bipartisan compromise. If so, why has Congress become increasingly acrimonious even though the American public wants it to be “bipartisan”? Many scholars claim that this is simply a breakdown of representation. We offer another explanation: although people profess support for “bipartisanship” in an abstract sense, what they desire procedurally out of their party representatives in Congress is to not compromise with the other side. To test this argument, we conduct two experiments in which we alter aspects of the political context to see how people respond to parties (not) coming together to achieve broadly popular public policy goals. We find that citizens’ proclaimed desire for bipartisanship in actuality reflects self-serving partisan desires.