Minnesota Settlement, Prairies & Restoration Frontenac Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules. -

Minnesota State Parks.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Afton State Park 4 2. Banning State Park 6 3. Bear Head Lake State Park 8 4. Beaver Creek Valley State Park 10 5. Big Bog State Park 12 6. Big Stone Lake State Park 14 7. Blue Mounds State Park 16 8. Buffalo River State Park 18 9. Camden State Park 20 10. Carley State Park 22 11. Cascade River State Park 24 12. Charles A. Lindbergh State Park 26 13. Crow Wing State Park 28 14. Cuyuna Country State Park 30 15. Father Hennepin State Park 32 16. Flandrau State Park 34 17. Forestville/Mystery Cave State Park 36 18. Fort Ridgely State Park 38 19. Fort Snelling State Park 40 20. Franz Jevne State Park 42 21. Frontenac State Park 44 22. George H. Crosby Manitou State Park 46 23. Glacial Lakes State Park 48 24. Glendalough State Park 50 25. Gooseberry Falls State Park 52 26. Grand Portage State Park 54 27. Great River Bluffs State Park 56 28. Hayes Lake State Park 58 29. Hill Annex Mine State Park 60 30. Interstate State Park 62 31. Itasca State Park 64 32. Jay Cooke State Park 66 33. John A. Latsch State Park 68 34. Judge C.R. Magney State Park 70 1 35. Kilen Woods State Park 72 36. Lac qui Parle State Park 74 37. Lake Bemidji State Park 76 38. Lake Bronson State Park 78 39. Lake Carlos State Park 80 40. Lake Louise State Park 82 41. Lake Maria State Park 84 42. Lake Shetek State Park 86 43. -

2009-2010 Winter Programs & Special Events Catalog

28 The Great Minnesota Ski Pass Get one and go! All cross-country skiers age 16 or older must have a Minnesota Ski Pass to use ski trails in state parks or state forests or on state or Grant-in-Aid trails. • You must sign your ski pass and carry it with you when skiing. • Rates are $5 for a daily ski pass, $15 for a one-season pass, and $40 for a three-season pass. • Ski pass fees help support and maintain Minnesota’s extensive cross-country ski trail system. • Daily ski passes are sold in park offices where weekend and holiday staff are available. Self-registration for one-season and three-season passes is available daily at all Minnesota state parks except Carley, George H. Crosby-Manitou, Monson Lake, and Schoolcraft. • You can also get daily, one-season, and three-season ski passes using Minnesota’s electronic licensing system, available at 1,750 locations around the state. To find a location near you, check the ELS page at mndnr.gov or call the DNR Information Center at 651-296-6157 or 1-888-646-6367. Metro Area Ski Trails 29 If you purchase a Minnesota ski pass for a special event such as candlelight ski event at a Minnesota state park, you may be wondering where else you can use it. Many cross-country ski trails throughout the state are developed and maintained with state and Grant-in-Aid funding. Grant-in-Aid trails are maintained by local units of government and local ski clubs, with financial assistance from the Department of Natural Resources. -

Campground Host Program

Campground Host Program MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF PARKS AND TRAILS Updated November 2010 Campground Host Program Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. You may email your completed application to [email protected] who will forward it to your first choice park. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Trails 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 Email: [email protected] 651-259-5607 Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. -

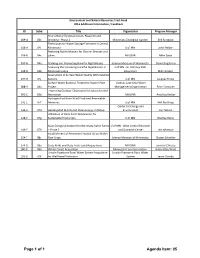

Of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd

Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund 2016 Additional Information / Feedback ID Subd. Title Organization Program Manager Prairie Butterfly Conservation, Research and 009‐A 03c Breeding ‐ Phase 2 Minnesota Zoological Garden Erik Runquist Techniques for Water Storage Estimates in Central 018‐A 04i Minnesota U of MN John Neiber Restoring Native Mussels for Cleaner Streams and 036‐B 04c Lakes MN DNR Mike Davis 037‐B 04a Tracking and Preventing Harmful Algal Blooms Science Museum of Minnesota Daniel Engstrom Assessing the Increasing Harmful Algal Blooms in U of MN ‐ St. Anthony Falls 038‐B 04b Minnesota Lakes Laboratory Miki Hondzo Assessment of Surface Water Quality With Satellite 047‐B 04j Sensors U of MN Jacques Finlay Surface Water Bacterial Treatment System Pilot Vadnais Lake Area Water 088‐B 04u Project Management Organization Brian Corcoran Improving Outdoor Classrooms for Education and 091‐C 05b Recreation MN DNR Amy Kay Kerber Hydrogen Fuel from Wind Produced Renewable 141‐E 07f Ammonia U of MN Will Northrop Center for Energy and 144‐E 07d Geotargeted Distributed Clean Energy Initiative Environment Carl Nelson Utilization of Dairy Farm Wastewater for 148‐E 07g Sustainable Production U of MN Bradley Heins Solar Energy Utilization for Minnesota Swine Farms U of MN ‐ West Central Research 149‐E 07h – Phase 2 and Outreach Center Lee Johnston Establishment of Permanent Habitat Strips Within 154‐F 08c Row Crops Science Museum of Minnesota Shawn Schottler 174‐G 09a State Parks and State Trails Land Acquisitions MN DNR Jennifer Christie 180‐G 09e Wilder Forest Acquisition Minnesota Food Association Hilary Otey Wold Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water System Acquisition Lincoln Pipestone Rural Water 181‐G 09f for Well Head Protection System Jason Overby Page 1 of 1 Agenda Item: 05 ENRTF ID: 009-A / Subd. -

Geologic History of Minnesota Rivers

GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF MINNESOTA RIVERS Minnesota Geological Survey Ed ucational Series - 7 Minnesota Geological Survey Priscilla C. Grew, Director Educational Series 7 GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF MINNESOTA RIVERS by H.E. Wright, Jr. Regents' Professor of Geology, Ecology, and Botany (Emeritus), University of Minnesota 'r J: \ I' , U " 1. L I!"> t) J' T II I ~ !oo J', t ' I' " I \ . University of Minnesota St. Paul, 1990 Cover: An early ponrayal of St. Anthony Falls on the Mississippi River In Minneapolis. The engraving of a drawing by Captain E. Eastman of Fan Snelling was first published In 1853; It Is here reproduced from the Second Final Report of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Minnesota, 1888. Several other early views of Minnesota rivers reproduced In this volume are from David Dale Owen's Report of a Geological Survey of Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota; and Incidentally of a portion of Nebraska Territory, which was published In 1852 by Lippincott, Grambo & Company of Philadelphia. ISSN 0544-3083 1 The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, religion, color, sex, national origin, handicap, age, veteran status, or sexual orientation. 1-' \ J. I,."l n 1 ~ r 1'11.1: I: I \ 1"" CONTENTS 1 .... INTRODUCTION 1. PREGLACIAL RIVERS 5 .... GLACIAL RIVERS 17 ... POSTGLACIAL RIVERS 19 . RIVER HISTORY AND FUTURE 20 . ... REFERENCES CITED iii GEOLOGIC HISTORY OF MINNESOTA RIVERS H.E. Wright, Jr. A GLANCE at a glacial map of the Great Lakes region (Fig. 1) reveals that all of Minnesota was glaciated at some time, and all but the southeastern and southwestern corners were covered by the last ice sheet, which culminated about 20,000 years ago. -

Quest for Excellence: a History Of

QUEST FOR EXCELLENCE a history of the MINNESOTA COUNCIL OF PARKS 1954 to 1974 By U. W Hella Former Director of State Parks State of Minnesota Edited By Robert A. Watson Associate Member, MCP Published By The Minnesota Parks Foundation Copyright 1985 Cover Photo: Wolf Creek Falls, Banning State Park, Sandstone Courtesy Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Dedicated to the Memory of JUDGE CLARENCE R. MAGNEY (1883 - 1962) A distinguished jurist and devoted conser vationist whose quest for excellence in the matter of public parks led to the founding of the Minnesota Council of State Parks, - which helped insure high standards for park development in this state. TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward ............................................... 1 I. Judge Magney - "Giant of the North" ......................... 2 II. Minnesota's State Park System .............................. 4 Map of System Units ..................................... 6 Ill. The Council is Born ...................................... 7 IV. The Minnesota Parks Foundation ........................... 9 Foundation Gifts ....................................... 10 V. The Council's Role in Park System Growth ................... 13 Chronology of the Park System, 1889-1973 ................... 14 VI. The Campaign for a National Park ......................... 18 Map of Voyageurs National Park ........................... 21 VII. Recreational Trails and Boating Rivers ....................... 23 Map of Trails and Canoe Routes ........................... 25 Trail Legislation, 1971 ................................... -

Situation Update EAB Minnesota

Situation Update EAB Minnesota Date and Time Completed: July 9, 2020 9:00 AM Update Period: January 29, 2020 to July 8, 2020 New Finds • Current EAB Status Map, www.mda.state.mn.us/eabstatus Survey • Faribault, MN (Rice County) Found within city at commercial property parking lot near downtown area. Find is about 10 miles north of previous find in Medford, MN (Steele County). • Racine, MN (Mower County) Found along roadside of Hwy 63 about 5 miles from previous find in Stewartville, MN. • New city finds within already quarantined counties: Bethel (Anoka), Columbus (Anoka), Jordan (Scott) Regulatory NOTICE: No Regulated Articles are legally allowed to move outside of a quarantine (untreated or treated), unless they are accompanied by a certificate or limited permit. Certificates and limited permits are only available when a compliance agreement is signed between the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and the firm interested in moving the regulated article. • Current Formal Quarantine • 23 Counties are now under EAB Quarantine o Two newest counties, Rice (March) and Mower (April) o Both are in Emergency Quarantine at this time, due to the Coronavirus Pandemic we have not been able to hold a public meeting. o Rice County was discovered after a city worker had attended the MDA Field Workshop on EAB identification. • Compliance Agreement Holders o 34 Active EAB Compliance Agreements o Mitigation methods - Mulch, firewood, composting, lumber, safeguarding • MDA Heat Treatment Certified means the company operates a kiln that has passed a rigorous inspection and testing process and has successfully demonstrated the ability to heat their firewood to a minimum core temperature of 140˚F for 60 minutes OR Heat Treatment for Various Wood Pests, 160⁰F for 75 minutes. -

Mississippi Blufflands State Trail Master Plan

Mississippi Blufflands State Trail Master Plan Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Division of Parks and Trails September 2016 Mississippi Blufflands State Trail Master Plan The Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Parks and Trails Division would like to thank all who participated in this master planning process. Individuals and groups in local communities have been working for years to support this trail. Many DNR staff, city, county and state officials, trail committee members, and local citizens contributed their time and energy to the planning process. Project Team: • Craig Blommer, area supervisor • Andrew Grinstead, planning specialist, Conservation Corps Minnesota & Iowa • Kevin Hemmingsen, regional trails specialist • Caleb Jensen, manager, Frontenac State Park • Darin Newman, planner Copyright 2016 State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources For more information on this management plan, please contact the DNR Parks and Trails Division at (651) 259-5600. This information can be made available in alternative formats such as large print, braille or audio tape by emailing [email protected] or by calling 651-259-5016. The Minnesota DNR prohibits discrimination in its programs and services based on race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, public assistance status, age, sexual orientation or disability. Persons with disabilities may request reasonable modifications to access or participate in DNR programs and services by contacting the DNR ADA Title II Coordinator at [email protected] or 651- 259-5488. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to Minnesota DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4049; or Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C. -

Special Places

UMMER ULY S 2017 (J ) Special Places PARKS & TRAILS COUNCIL OF MINNESOTA NEWSLETTER ers My ifer Jenn Big Bog State Rec Area by Inside this issue LETTER FROM BRETT .............................PG 2 TRAIL COUNTERS GO UP .....................PG 3 LEGISLATIVE RECAP ...........................PG 4-5 NOISE ...................................................PG 6 ST. CROIX SP PLAN ...............................PG 6 MILL TOWNS TRAIL OPENS ..................PG 7 DR. DOROTHY ANDERSON ..................PG 8 FRONTENAC & FRIENDS ................... PG 11 rd 3 Annual Atop bluff Parks & Trails Council acquired for Frontenac with lakelet leading into Lake Pepin. Photo Contest! Land Project Update Enter thru Aug. 20, 2017 3 CATEGORIES Adding a new view to Frontenac State Park t the entrance to Frontenac State of this land’s natural beauty, you would Park lays 161.33 acres of land need to climb its blu, which looks thatA has been a farm, a (unsanctioned) out in the opposite direction from landll and an explosion reenact- park’s famous Lake Pepin overlooks. ment testing grounds. Yet, its scenic From atop the newly acquired, peace- vistas and proximity to the state park ful blu you will see the meandering foreshadowed other uses. In May the waters of the lakelet and creek that fate of this land was sealed as Parks & wrap around the southern end of the Trails Council purchased it to become park and ow into Lake Pepin. part of the park. is view (photo above) is what If you’ve ever visited the park you’ve captured the attention of Parks & glimpsed this land, which is along Trails Council’s then president Mike $300 in prizes for 1st - 3rd places Highway 2, just north of the bridge Tegeder as he visited with members of See all the entries & submit your photos at crossing the Pleasant Valley Lakelet the Frontenac State Park Association www.parksandtrails.org and Creek. -

Sanitary Disposals Alabama Through Arkansas

SANITARY DispOSAls Alabama through Arkansas Boniface Chevron Kanaitze Chevron Alaska State Parks Fool Hollow State Park ALABAMA 2801 Boniface Pkwy., Mile 13, Kenai Spur Road, Ninilchik Mile 187.3, (928) 537-3680 I-65 Welcome Center Anchorage Kenai Sterling Hwy. 1500 N. Fool Hollow Lake Road, Show Low. 1 mi. S of Ardmore on I-65 at Centennial Park Schillings Texaco Service Tundra Lodge milepost 364 $6 fee if not staying 8300 Glenn Hwy., Anchorage Willow & Kenai, Kenai Mile 1315, Alaska Hwy., Tok at campground Northbound Rest Area Fountain Chevron Bailey Power Station City Sewage Treatment N of Asheville on I-59 at 3608 Minnesota Dr., Manhole — Tongass Ave. Plant at Old Town Lyman Lake State Park milepost 165 11 mi. S of St. Johns; Anchorage near Cariana Creek, Ketchikan Valdez 1 mi. E of U.S. 666 Southbound Rest Area Garrett’s Tesoro Westside Chevron Ed Church S of Asheville on I-59 Catalina State Park 2811 Seward Hwy., 2425 Tongass Ave., Ketchikan Mile 105.5, Richardson Hwy., 12 mi. N of on U.S. 89 at milepost 168 Anchorage Valdez Tucson Charlie Brown’s Chevron Northbound Rest Area Alamo Lake State Park Indian Hills Chevron Glenn Hwy. & Evergreen Ave., Standard Oil Station 38 mi. N of & U.S. 60 S of Auburn on I-85 6470 DeBarr Rd., Anchorage Palmer Egan & Meals, Valdez Wenden at milepost 43 Burro Creek Mike’s Chevron Palmer’s City Campground Front St. at Case Ave. (Bureau of Land Management) Southbound Rest Area 832 E. Sixth Ave., Anchorage S. Denali St., Palmer Wrangell S of Auburn on I-85 57 mi.