Financial Market Bubbles and Crashes, Second Edition Harold L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Capital Market on the Economic Growth in Oman

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Alam, Md. Shabbir; Hussein, Muawya Ahmed Article The impact of capital market on the economic growth in Oman Financial Studies Provided in Cooperation with: "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), Romanian Academy Suggested Citation: Alam, Md. Shabbir; Hussein, Muawya Ahmed (2019) : The impact of capital market on the economic growth in Oman, Financial Studies, ISSN 2066-6071, Romanian Academy, National Institute of Economic Research (INCE), "Victor Slăvescu" Centre for Financial and Monetary Research, Bucharest, Vol. 23, Iss. 2 (84), pp. 117-129 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231680 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory

2021 A Primer on Modern Monetary Theory Steven Globerman fraserinstitute.org Contents Executive Summary / i 1. Introducing Modern Monetary Theory / 1 2. Implementing MMT / 4 3. Has Canada Adopted MMT? / 10 4. Proposed Economic and Social Justifications for MMT / 17 5. MMT and Inflation / 23 Concluding Comments / 27 References / 29 About the author / 33 Acknowledgments / 33 Publishing information / 34 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 35 Purpose, funding, and independence / 35 About the Fraser Institute / 36 Editorial Advisory Board / 37 fraserinstitute.org fraserinstitute.org Executive Summary Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a policy model for funding govern- ment spending. While MMT is not new, it has recently received wide- spread attention, particularly as government spending has increased dramatically in response to the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and concerns grow about how to pay for this increased spending. The essential message of MMT is that there is no financial constraint on government spending as long as a country is a sovereign issuer of cur- rency and does not tie the value of its currency to another currency. Both Canada and the US are examples of countries that are sovereign issuers of currency. In principle, being a sovereign issuer of currency endows the government with the ability to borrow money from the country’s cen- tral bank. The central bank can effectively credit the government’s bank account at the central bank for an unlimited amount of money without either charging the government interest or, indeed, demanding repayment of the government bonds the central bank has acquired. In 2020, the cen- tral banks in both Canada and the US bought a disproportionately large share of government bonds compared to previous years, which has led some observers to argue that the governments of Canada and the United States are practicing MMT. -

Neo-Liberalism As Financialisation1 Engaging Neo-Liberalism When It

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Neo-liberalism as Financialisation 1 Engaging Neo-liberalism When it first emerged, neo-liberalism seemed to be able to be defined relatively easily and uncontroversially. In the economic arena, the contrast could be made with Keynesianism and emphasis placed on perfectly working markets. A correspondingly distinctive stance could be made over the role of the state as corrupt, rent-seeking and inefficient as opposed to benevolent and progressive. Ideologically, the individual pursuit of self-interest as the means to freedom was offered in contrast to collectivism. And, politically, Reaganism and Thatcherism came to the fore. It is also significant that neo-liberalism should emerge soon after the post-war boom came to an end, together with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. This is all thirty or more years ago and, whilst neo-liberalism has entered the scholarly if not popular lexicon, it is now debatable whether it is now or, indeed, ever was clearly defined. How does it fair alongside globalisation, the new world order, and the new imperialism, for example, as descriptors of contemporary capitalism. Does each of these refer to a similar understanding but with different terms and emphasis? And how do we situate neo-liberalism in relation to Third Wayism, the social market, and so on, whose politicians, theorists and ideologues would pride themselves as departing from neo- liberalism but who, in their politics and policies, seem at least in part to have been captured by it (and even vice-versa in some instances)? These conundrums in the understanding and nature of neo-liberalism have been highlighted by James Ferguson (2007) who reveals how what would traditionally be termed progressive policies (a basic income grant for example) have been rationalised through neo-liberal discourse. -

Scope and Function of the Capital Market in the American Economy

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Flow of Capital Funds in the Postwar Economy Volume Author/Editor: Raymond W. Goldsmith Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-870-14112-0 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gold65-1 Publication Date: 1965 Chapter Title: Scope and Function of the Capital Market in the American Economy Chapter Author: Raymond W. Goldsmith Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c1680 Chapter pages in book: (p. 22 - 42) CHAPTER 1 Scope and Function of the Capital Market in the American Economy Origin of the Capital Market in the Separation of Saving and Investment A MARKET for new capital, apart from transactions in existing finan- cial and real assets, exists because in a modern economy saving (the excess of current income over current expenditures on consumption) is to a large extent separated from investment, i.e., expenditures on durable assets usually defined as new construction, equipment, and additionstoinventories and excluding education,research, and health.1 In any given period every economic unit either saves or dissaves— if we ignore the relatively few units whose current expenditures ex- actly balance their current income; and most units make capital expenditures, which usually involve payments to other units for fin- ished durable goods, materials, or labor, but which may also be internal and imputed (e.g., Crusoe building his boat). Both saving and investment may be calculated gross or net of capital consumption allowances or retirements. Since these diminish saving and investment equally, the difference between saving and investment is the same whether calculated on a gross or net basis. -

Economics Modern Monetary Theory

Economics Modern monetary theory: no magic bullet ● Can the economic problems of our time be solved by a new monetary theory? The Key macro reports so-called “modern monetary theory” (MMT) has been attracting attention in the US for some time, because it questions proven economic principles and is being Understanding Germany: A championed by prominent US politicians on the left. The debate is no longer last golden decade ahead limited to the US, but has been taken up by experts in Germany, Europe and October 2010 Australia. So, what is behind MMT? Euro crisis: The role of the ● According to MMT, the central bank and its monetary policy become the ECB extended arm of the state. A thrifty state is no longer necessary because it can 29 July 2011 finance itself directly through its central bank and by creating new money. The lessons of the crisis: According to conventional theory, such a policy would pose a considerable risk of what Europe needs inflation. 27 June 2014 ● However, recent central bank policy could be interpreted in such a way that the After Trump: notes on the feared danger of inflation does not arise in practice, and the propositions of MMT perils of populism are validated. Massive bond purchase programmes have made leading central 14 November 2016 banks important creditors of their own countries. The Bank of Japan already holds more than 40% of its own government’s bonds without any significant consumer Reforming Europe: which price inflation in Japan. ideas make sense? 19 June 2017 ● In this context, some are calling for the high levels of government debt held by central banks to be simply cancelled; however, we consider MMT implications of Notes on the inflation this nature to be extremely dangerous. -

The Role of Capital Market in Emerging Economy

THE ROLE OF CAPITAL MARKET IN EMERGING ECONOMY Dr(Mrs) P.A Isenmila Department of Accounting, Faculty of Management Sciences University of Benin Akinola Adewale O GT Bank, Uselu Lagos Road, Benin City ABSTRACT In recent times there has been a growing concern on the role of capital markets in Africa in stimulating economic progress. The argument that African economies may be lagging and that the capital markets may not be providing the needed impetus for financial intermediation and economic progress has been put forward by few number of researchers. A peculiar experience in most African economies is that the challenges with good quality institutions such as democratic accountability could have resulted to the weak capital market development in Africa because they increase political risk and reduce the viability of external finance. This study evaluates capital market and developing economies, challenges to capital market growth, the capital market in Nigeria, capital market and economic growth in Nigeria and policy directions for promoting capital market growth in developing countries. Keywords: capital market, emerging economies, economic growth 1. INTRODUCTION Stimulating economic growth and development requires long term funding, far longer than the duration for which most savers are willing to commit their funds and this constitutes a barrier to economic growth. In this regard, the capital market provides an avenue for the mobilization and utilization of long-term funds for development and hence it is referred to as the long term end of the financial system. Over the past few decades, globally there has been an upsurge in capital market activity, and emerging markets have accounted for a large amount of this boom. -

The Political Economy of Capitalism

07-037 The Political Economy of Capitalism Bruce R. Scott Copyright © 2006 by Bruce R. Scott Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. #07-037 Abstract Capitalism is often defined as an economic system where private actors are allowed to own and control the use of property in accord with their own interests, and where the invisible hand of the pricing mechanism coordinates supply and demand in markets in a way that is automatically in the best interests of society. Government, in this perspective, is often described as responsible for peace, justice, and tolerable taxes. This paper defines capitalism as a system of indirect governance for economic relationships, where all markets exist within institutional frameworks that are provided by political authorities, i.e. governments. In this second perspective capitalism is a three level system much like any organized sports. Markets occupy the first level, where the competition takes place; the institutional foundations that underpin those markets are the second; and the political authority that administers the system is the third. While markets do indeed coordinate supply and demand with the help of the invisible hand in a short term, quasi-static perspective, government coordinates the modernization of market frameworks in accord with changing circumstances, including changing perceptions of societal costs and benefits. In this broader perspective government has two distinct roles, one to administer the existing institutional frameworks, including the provision of infrastructure and the administration of laws and regulations, and the second to mobilize political power to bring about modernization of those frameworks as circumstances and/or societal priorities change. -

Neoliberalism, Capital Accumulation, and Austerity in Academia, the Term

Neoliberalism, Capital Accumulation, and Austerity Mehdi S. Shariati, Ph.D. Professor, Economics, Sociology and Geography Kansas City Kansas City Community College Abstract Recent crisis in global capitalism has once again brought to the fore major structural contradictions and the consequences of these contradictions are reflected in the massive dislocation of the economy, growing number of (the) poor, concentration of wealth in the hands of a few around the globe, indebtedness, rampant speculation and an unprecedented concentration of financial capital at the expense of productive sector of the economy. The austerity program by which the global working class must endure has generated much social protests including "occupy Wall Street," but with very little discussion of an alternative to the current global system. In academia, the term descriptive of finance capital’s policy prescription is “neoliberalism.” Yet the term not only has created confusion since in the North American context, liberals and neoliberals have always been viewed as left leaning people and not the free marketers and market fundamentalists. Neoliberalism often refers to a set of economic policies designed for intense and accelerated capital accumulation. Rarely the discussion of the process of intense capital accumulation includes a restructuring of society and social institutions as a precondition for the successful implementation of the policies. This paper is an attempt to add to the discussion by pointing out the indispensability of the practice of social imperialism in the process of reproducing the hegemonic structure and effective implementation of the policy. Reaction to the evolving socio-economic and political events has been one of the greatest preoccupation in the social and political sciences as a habit and of necessity. -

Privatization As a Vehicle for Promoting Capital Market

Privatization as a vehicle for promoting capital market development and financial inclusion Privatization is the process of transferring ownership of a business, enterprise, agency, public service, or public property from the public sector (a government) to the private sector. There are varieties of methods or approaches that may be opted to sale state-owned enterprises. The choice of privatisation method depends on the government’s privatization policy objectives, the market environment and the characteristics and size of the company that is being sold. The key methods for privatization are: (a) public share offerings on the stock market; (b) trade or private sales; (c) employee and management buyouts; (d) mixed sales (combination of the above). Choice of sale method is influenced by the capital market, political, and companies-specific factors. Public offering through the stock market can used to broaden and deepen domestic capital markets, boosting liquidity and (potentially) economic growth, but in cases where the capital markets are insufficiently developed it may be difficult to find enough retail and institutional investors (buyers), and transaction costs (and in some cases under pricing) cases may be higher. Typically, public share offerings have been the predominant method of privatization, the vast majority of privatisation proceeds in most developed countries have been through public offering of shares on the stock market. This has particularly been the case in the larger economies such as the UK, Italy, France and Germany, reflecting the size of assets sold and the explicit or implicit policy objective of deepening and widening equity markets. For example, public share offering have accounted for close to 90% of the Italian privatization proceeds from 1992 when the programme started. -

Short Selling's Positive Impact on Markets and the Consequences Of

Short Selling’s Positive Impact on Markets and the Consequences of Short-Sale Restrictions I. Introduction Short selling plays an important role in efficient capital markets, conferring positive benefits by facilitating secondary market trading of securities through improved price discovery and liquidity, while also positively impacting corporate governance and, ultimately, the real economy. However, short selling and short sellers have received negative attention over the years, primarily due to general concerns that short selling is purely speculative and potentially destabilizing for markets.1 Short sellers are often scapegoats in a market down cycle,2 while firm management is also generally wary of short sellers, as short selling positions pay off when a firm’s stock price declines.3 However, to the extent that short selling improves the efficiency of capital markets, many of these criticisms appear to be unwarranted. Recent policy proposals and discussions on the role of short selling in our capital markets focus on mandatory public disclosure requirements for short sale transactions. The “Brokaw Act,” introduced in the Senate Banking Committee in August 2017, would require short sellers to file public disclosure statements after accumulating short interests of 5% or more of a company’s stock.4 Advocates of this proposal point to the disclosure requirements for long positions, arguing that a similar requirement for short positions would be appropriate.5 However, the rationale for disclosure requirements for long positions are related to voting rights and control, and there is no analogous rationale for short positions, as those powers do not accrue to short sellers. More recently, a similar legislative proposal has been pushed by a group of proponents that includes the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. -

Bubbles in History

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Quinn, William; Turner, John D. Working Paper Bubbles in history QUCEH Working Paper Series, No. 2020-07 Provided in Cooperation with: Queen's University Centre for Economic History (QUCEH), Queen's University Belfast Suggested Citation: Quinn, William; Turner, John D. (2020) : Bubbles in history, QUCEH Working Paper Series, No. 2020-07, Queen's University Centre for Economic History (QUCEH), Belfast This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/224837 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu QUCEH WORKING PAPER SERIES http://www.quceh.org.uk/working-papers BUBBLES IN HISTORY William Quinn (Queen’s University Belfast) John D. -

How We Explain the Chinese Stock Market Bubble?

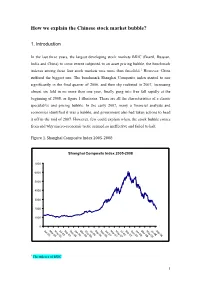

1 However, China ese stock market bubble? pricing bubble, the benchmark oping stock markets BRIC (Brazil,cketed Russian, in 2007, increasing aracteristics of a classic ets rose more than threefold. tent subjected to an asset How we explain the Chin ment also had taken actions to head ly 2007, many a financial analysts and rter of 2006, and then sky ro 1. Introduction strates. These are all the ch ould explainso ineffective where th eand stock failed bubble to halt. comes In the last three years, the largest devel India and China) to some ex indexes among these four stock mark suffered the biggest one. The benchmark Shanghai Composite index started to rise significantly in the final qua almost six fold in no more than one year, finally gang into free fall rapidly at the beginning of 2008, as figure 1 illu speculative and pricing bubble. In the ear Sep‐08 economics identified it was a bubble, and govern Jul‐08 Shanghai Composite Index 2005-2008 May‐08 it off in the mid of 2007. However, few c Mar‐08 from and why macro-economic tactic seemed Jan‐08 Nov‐07 1 Sep‐07 Figure 1. Shanghai Composite Index 2005‐2008 Jul‐07 May‐07 Mar‐07 Jan‐07 7000 Nov‐06 Sep‐06 6000 Jul‐06 5000 May‐06 Mar‐06 4000 Jan‐06 Nov‐05 3000 Sep‐05 Jul‐05 2000 May‐05 Mar‐05 1000 0 Jan‐05 1 The indexes of BRIC Since the movement of stock prices is caused by the actions of investors, asset pricing bubbles ultimately have to be traced back to the beliefs of investors.