Gut Microbiome and Human Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fiber to Enrich Product Appeal

INCREASE FIBER. RETAIN APPEAL. REDUCE COST-IN-USE. A fiber to enrich product appeal Support digestive wellness — without impacting taste, texture or color using NOVELOSE® 3490 dietary fiber The call for fiber and digestive health is getting louder. Forty-four percent of U.S. consumers are increasing fiber consumption.1 And 70% of consumers feel digestive health is “important.”2 As you formulate to support digestive wellness with more fiber, you must overcome the unappealing effects fiber can often have on taste, texture and appearance — and for some consumers, digestive comfort — to keep consumers coming back for more. Now, NOVELOSE 3490 dietary fiber from Ingredion can help you deliver just-right taste, texture, and even fewer calories in fiber–rich baked goods, tortillas, cereal and bars. And, it’s Low FODMAP Certified to help you bring fiber to consumers who follow a low FODMAP diet. Take the lead in fiber fortification to support digestive wellness Adding fiber to many commonly consumed foods can be a challenge. You must balance the positive health benefits and label claims with the potentially negative impact of fiber on taste, texture and appearance. Not anymore. New NOVELOSE® 3490 resistant starch (type RS4) is an insoluble fiber that has little to no impact on taste, color or texture. By replacing a portion of the flour in bread, baked snacks, cookies, tortillas, cereal and bars, the tapioca-based fiber reduces calories and enables processing ease. It also reduces cost-in-use compared to many other fibers. Meet the growing low FODMAP trend Give consumers the fiber — and taste they want without digestive discomfort Many foods found in American diets are high in in certain short- chain carbohydrates called FODMAPs, which can trigger occasional digestive discomfort. -

Low FODMAP Food Chart Ibsdiets.Org

Low FODMAP Food Chart IBSDiets.org Low FODMAP High FODMAP Vegetables and Legumes Bamboo shoots Garlic Bean sprouts Onions Broccoli (3/4 cup) Aparagus Cabbage, common and red (3/4 cup) Beans e.g. black, broad, kidney, lima, soya Carrots Cauliflower Celery (less than 5cm stalk) Cabbage, savoy Chick peas (1/4 cup max) Mange tout Corn (1/2 cob max) Mushrooms Courgette / Zucchini (65g) Peas Scallions / spring onions (white part) Cucumber Eggplant (1 cup) Green beans Green pepper (1/2 cup) Kale Lettuce e.g. Butter, iceberg, rocket Parsnip Potato Pumpkin Red peppers Scallions / spring onions (green part) Squash Sweet potato (1/2 cup) Tomatoes (1 small) Turnip (1/2 turnip) Fruit Bananas, unripe (1 medium) Apples Blueberries (1/4 cup) Apricot Cantaloupe (3/4 cup) Avocado Cranberry Bananas, ripe Clementine Blackberries Grapes Grapefruit Melons e.g. Honeydew, Galia (1/2 cup) Mango Kiwifruit (2 small) Peaches Lemon Pears Orange Plums Pineapple Raisins Raspberry (30 berries) Sultanas Rhubarb Watermelon Strawberry For up to date and extensive information go to www.IBSDiets.org Meat and Substitutes Beef Sausages (check ingredients) Chicken Processed meat (check ingredients) Lamb Pork Quorn mince Cold cuts e.g. Ham and turkey breast Breads, Cereals, Grains and Pasta Oats Barley Quinoa Bran Gluten free foods e.g. breads, pasta Cous cous Savory biscuits Gnocchi Buckwheat Granola Chips / crisps (plain) Muesli Cornflour Muffins Oatmeal (1/2 cup max) Rye Popcorn Semolina Pretzels Spelt Rice e.g. Basmati, brown, white Wheat foods e.g. Bread, cereal, pasta -

SIBO Bi Phasic Diet Serves 2

Phase 7 DAY SIBO Meal Plan 1 serves 2 Phase 1 | Restricted | SIBO Bi Phasic Diet Rebecca Coomes 1 the healthy gut Join us for our latest SIBO recipes, articles, interviews with leading specialists, SIBO cookbooks and more. THE HEALTHY GUT THE HEALTHY thehealthygut.com © The Healthy Gut 2018 Recipes: Rebecca Coomes All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed Editor: Rebecca Coomes and Kate Saunders-Morgan in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or stored in a database or First published in Australia in 2017 Creative Director: Rebecca Coomes retrieval system, without prior written permission from The Healthy Gut. by The Healthy Gut Design and typesetting: Yedah Merino Designs The information in this book is for information purposes only. It is not intended PO Box 1405 Photographers: Aliki Dimitrakopoulos and Rebecca Coomes nor implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Please consult Camberwell East VIC 3126 Prop and food styling: Aliki Dimitrakopoulos and Rebecca Coomes your healthcare provider to discuss your personal healthcare requirements or Food preparation: Rebecca Coomes treatment plan. Reading the information in this book does not create a physician- patient relationship. 2 contents 4 The SIBO Bi-Phasic Diet Protocol 36 SIBO Cookbooks contents contents 5 The SIBO Bi-Phasic Diet Phases 37 Live Well With SIBO 6 Food Tables 10 Meal Plan 11 Recipe Index 12 Shopping List 13 Breakfasts 18 Lunches 22 Dinners 31 Extras 24 the SIBO bi-phasic diet protocol This meal plan has been developed in compliance with Dr. Nirala Jacobi’s SIBO Bi-Phasic Diet protocol and has a range of recipes that are suitable for the Restricted phase of the diet. -

The Low FODMAP Diet

The Low FODMAP Diet FOOD GROUP FOODS TO AVOID FOODS TO TRY INSTEAD Grains Foods made from wheat or wheat Rice, corn tortilla chips, gluten-free flour including: bread, cereal grains (like buckwheat and quinoa), and pasta foods made with gluten-free flour Fruits Apples, avocado, ripe bananas, Unripe bananas, most types of watermelon, grapefruit, pears, berries, grapes, cantaloupe, oranges, peaches, plums, most canned or pineapple, kiwi, rhubarb dried fruits Vegetables Garlic, onion, asparagus, beets, Bell peppers, cucumbers, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, black beans, lettuce, potatoes, tomatoes, kidney beans, peas corn, celery, green beans Meats & Proteins Most processed meats, meat served Beef, chicken, canned tuna, eggs, in fruit sauces, chorizo, sausage, most fish, lamb, pork, turkey, pistachios, cashews sunflower seeds, peanuts Dairy Milk (from cow, sheep or goat), Dairy-free milk, hard cheeses, half buttermilk, sour cream, yogurt, and half, mozzarella, sherbet, small some soft cheeses, ice cream, amounts of cream cheese sweetened condensed milk Non-Dairy Alternatives Almond milk, hemp milk, rice milk, Soy products, coconut cream oat milk Beverages Fruit and vegetable juices from Fruit and vegetable juices made high FODMAP foods (apple juice, from low FODMAP foods (orange grapefruit juice), coconut water, juice, tomato juice), coffee, herbal drinks with high-fructose corn syrup tea, water Condiments, High-fructose corn syrup, agave, honey, Balsamic vinegar, olive oil, soy Seasonings, most jams and jellies, relish, hummus, sauce, mayo, mustard, garlic infused Sweeteners artificial sweeteners, any sauces or oil, sugar, salt, pepper, most herbs, dressings made with high FODMAP small amounts of marinara sauces foods or high-fructose corn syrup To make an appointment with a gastroenterologist, visit henryford.com or call 1-800-HENRYFORD (436-7936). -

Nutrition Update for IBD

Nutrition Update for IBD Nneka Ricketts-Cameron, RD and Tamara Sims-Dorway, RD Arnold Palmer Medical Center is nationally ranked by U.S. News & World Report as one of the 2014-2015 “Best Children’s Hospitals” in Gastroenterology & GI Surgery Objectives • Identify possible nutrient deficiencies for patients with IBD • Review of diet interventions Nutrient Deficiencies • Protein – increased needs due to losses from inflammation • Calories – poor intake during flares • Vitamin D – prednisone known to induce state of vitamin D resistance • Iron – blood losses (more prevalent with UC) • Folate – medications such as methrotrexate and sulphasalazine • Vitamin B12 - surgical resection of stomach or terminal ileum • Calcium – avoidance of lactose, corticosteroids, malabsorption, poor bone density • Magnesium – increased intestinal losses • Zinc – excessive stool losses or high output fistulas Alternative Diets Specific Carbohydrate Diet • Created in mid-20th century by gastroenterologist to treat celiac disease • Became popular in the 1990’s for IBD • Limits all grains and sugar except for fructose in the form of honey • Restricts most milk products except for fully fermented yogurt (home made) • Restricts canned vegetables and fruit juices • Includes unprocessed meat, fish, eggs, vegetables, nuts, most fruits (fresh, frozen or dried) without additives Alternative Diets Specific Carbohydrate Diet Pros Cons • Eliminates processed foods and • Rigid and difficult to maintain additives • Psychologically stressful for • Appeals to individuals with -

What Is the Low-FODMAP Diet?

LOW-FODMAP DIET What Is the Low-FODMAP Diet? FODMAP refers to a group of five sugars found in certain foods. These sugars are lactose, fructose (in excess), fructans, galactans and polyols. Specifically, FODMAP stands for: • Fermentable • Oligosaccharides • Disaccharides • Monosaccharides • And • Polyols For some people, FODMAPs are poorly absorbed and can cause symptoms: • Bloating or swelling in your belly. • Gas. • Belly pain. • Nausea. • Diarrhea (loose stool). • Constipation (hard stool or trouble passing stool). The low-FODMAP diet has three phases. 1. Eliminate. 2. Reintroduce. 3. Liberatation. The information provided by the AGA Institute is not medical advice and should not be considered a replacement for seeing a medical professional . July 2017 Page 1 of 2 © AGA 2017 It is very important to work with your doctor or dietitian when thinking about following the low-FODMAP diet. Do not start the low-FODMAP diet until your doctor or dietitian tells you to and gives you detailed instructions on how to follow the diet the right way. Please refer to the full list of high-FODMAP foods in the “Getting Started” section. The information provided by the AGA Institute is not medical advice and should not be considered a replacement for seeing a medical professional . July 2017 Page 2 of 2 © AGA 2017 LOW-FODMAP DIET Who Should Be on the Low- FODMAP Diet? Certain health conditions can be helped by the low-FODMAP diet. These health issues include: • Irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D). • Irritable bowel syndrome-mixed (both diarrhea and constipation; IBS-M). • Functional diarrhea (chronic loose stool with no belly pain). -

Popular Diets

Popular Diets Wendy Dahl, PhD Associate Professor and Extension Specialist UF/IFAS Food Science & Human Nutrition Dept. [email protected] 1 Webinar Team Wendy Dahl, Ph.D. Julie England, M.S.,CFCS Associate Professor and Extension Specialist Seminole County FCS & Food Wendy Wood Lynch, M.S. UF/IFAS Food Science & Human Nutrition Depart. Systems Extension Agent Putnam County FCS Extension Agent [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 Saturday Evening Post September 22nd 1934 • Walking is becoming a lost art! - one car for every 5 people! • Perpendicular diet – limiting to one, two or a few foods • Horizontal diet – a variety of foods – but less • A 18-day Hollywood Diet ‘What day are you on?’ 3 4 It’s not just about weight loss, but also perceived health benefits. Are we destined to repeat history? 5 Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 www.thelancet.com Published online April 3, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8 6 Mediterranean Dietary Pattern Associated with decreased chronic disease risk: Olive oil ↓ Cardiovascular disease (Grosso et al. 2015) Fruit ↓ High blood pressure (Nissensohn et al. 2016) ↓ Metabolic syndrome (Godos et al. 2017) Vegetables ↓ Cancers (Schwingshackl & Hoffman 2015) Whole grains ↓ Type 2 Diabetes (Jannasch et al. 2017) Nuts and seeds ↓ Cognition (Solfrizzi et al. 2017) Legumes/pulses Some evidence for lower central obesity Fish and lean meats (Bendall et al. 2018) but weight loss requires eating less Limiting red meat, butter, *Also effective for managing chronic disease sweetened beverages, e.g. -

Diet and Nutrients in Gastrointestinal Chronic Diseases

nutrients Review Diet and Nutrients in Gastrointestinal Chronic Diseases Antonio Corsello 1,* , Daniela Pugliese 1, Antonio Gasbarrini 1,2 and Alessandro Armuzzi 1,2 1 OU Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, 00168 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (D.P.); [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Istituto di Patologia Speciale Medica, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Largo F. Vito 1, 00168 Rome, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-380-381-0206 Received: 15 July 2020; Accepted: 1 September 2020; Published: 3 September 2020 Abstract: Diet and nutrition are known to play key roles in many chronic gastrointestinal diseases, regarding both pathogenesis and therapeutic possibilities. A strong correlation between symptomatology, disease activity and eating habits has been observed in many common diseases, both organic and functional, such as inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. New different dietary approaches have been evaluated in order improve patients’ symptoms, modulating the type of sugars ingested, the daily amount of fats or the kind of metabolites produced in gut. Even if many clinical studies have been conducted to fully understand the impact of nutrition on the progression of disease, more studies are needed to test the most promising approaches for different diseases, in order to define useful guidelines for patients. Keywords: nutrition; gastrointestinal diseases; pediatrics; feeding disorders; functional gastrointestinal disorders; enteral nutrition; inflammatory bowel disease; irritable bowel syndrome 1. Introduction Nutrition and its various facets play a fundamental role in the development and growth of the individual, both directly and indirectly modifying all physiological phenomena during the course of life [1]. -

Low FODMAP Diet

Low FODMAP Diet FODMAP? What does that stand for? Fermentable Oligosaccharides (oligo –“few,” saccharide – “sugar”) Disaccharides (“two sugars”) Monosaccharides (“one sugar”) And Polyols (these are sugar alcohols) OK, but what are FODMAPs and who should avoid them? FODMAPs are a type of carbohydrate, or “sugar,” found in certain foods. Carbohydrates give us energy, along with fat and protein. People with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a slow moving gut, or other bowel disorder may not tolerate foods with FODMAPS. This is because FODMAPS are not easily absorbed by the bowel. Symptoms of FODMAP intolerance include gas, abdominal discomfort, distention, bloating, fullness, nausea, and/or pain after eating foods containing FODMAPS. Foods that do not contain carbohydrates are not a concern. This includes meat, poultry, fish, eggs, butter, oils, and hard cheeses. Carbohydrates that are Considered FODMAPS Fructans and Galactans Polyols Fructose Sorbitol Lactose Mannitol Fructooligosaccharides Xylitol Galactooligosaccharides Maltitol Fructose Fructose is a naturally occurring sugar found in fruit, vegetables, and honey. Fruits and fruit juices with higher levels of fructose may cause gas, bloating, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. For some people, even a small amount of fruit juice may worsen symptoms. Updated BB 12-2016 www.GInutrition.virginia.edu Glucose is also a naturally occurring sugar. Fruits and juices with more glucose (and less fructose) may be more “intestine friendly.” The tables in the following section list which fruits, juices, and other foods may be better choices if you have FODMAP intolerance. High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS) HFCS is an ingredient in many processed foods. HFCS is made up of almost half glucose and half fructose, similar to regular table sugar (i.e., “sucrose”). -

What Is the Low FODMAP Diet?

What is the Low FODMAP Diet? Low FODMAP Dietary Handout Created For Gastroenterology Associates of Columbus Columbus, Mississippi What is it? FODMAPs are a group of small chain carbohydrates (sugar and fibers) that are commonly found in everyday foods. FODMAPs is an acronym that stands for: F: Fermentable O: Oligosaccharides (fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides-GOS) D: Disaccharides (lactose, milk sugar) M: Monosaccharides (excess fructose) A: And P: Polyols (sugar alcohols such as sorbitol or mannitol)1 Where are they found? FODMAPs are found in dairy products, wheat, and some fruits and vegetables. Here are some common high FODMAP foods to avoid! How do they work? ➢ They pull water from the gut into the intestinal tract (osmotic) ➢ FODMAPS are not well digested or absorbed in everyone, especially those who are sensitive ➢ If eaten in excess, the bacteria in the intestinal tract can ferment leading to gas, bloating, cramping, and diarrhea2 What are the benefits? A diet low in FODMAPs can help reduce symptoms (gas, bloating, cramping, diarrhea). A low FODMAPs diet is often used in people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), and in those with other digestive disorders who are sensitive to FODMAPs.2 The Three Phases of the Low FODMAP Diet So what can I eat? It may seem overwhelming but there are a LOT of low FODMAP foods that are available! It can take some time to get used to but there are great options and alternatives available. For a comprehensive list of low FODMAP foods to eat and high FODMAP foods to avoid see the end of the packet. -

Low-FODMAP Nutrition Therapy

Prepared For: Date: Prepared By: Contact: Low-FODMAP Nutrition Therapy FODMAP is an acronym that stands for: Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. These are foods components that are restricted in a low-FODMAP diet. This diet is prescribed to reduce symptoms in those who have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Gut bacteria can ferment food components when eaten in Fermentable large portions. This can result in bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Fructan sources: Wheat, rye, garlic, onion, leeks, and artichokes Oligosaccharides Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) sources: Beans, lentils, soybeans, and nuts, including cashews Lactose sources: Disaccharides Dairy products and ingredients from cow, goat, or sheep’s milk Fructose sources: Monosaccharides Certain fruits, honey, and high-fructose corn syrup AND -- Sources: sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, erythritol, xylitol, and isomalt, Polyols apricots, avocados, cherries, nectarines, peaches, and plums and mushrooms Tips Fiber is a part of carbohydrate that is not digested by your body. Fiber is found in plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes (dried beans, peanuts). Since some high-fiber foods are also high FODMAP, this diet may limit your fiber intake. Carefully plan your meals to include alternative fiber sources. The FODMAP diet can safely include low FODMAP sources of fiber. Your registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) will help you include appropriate fruits, vegetables, and whole grains for this diet. Patients who have IBS and constipation may benefit from eating more fiber. However, if you have IBD and constipation, eating more fiber is not recommended (unless you are in remission and do not have any strictures). -

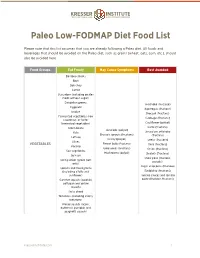

Paleo Low-FODMAP Diet Food List.Pages

! Paleo Low-FODMAP Diet Food List Please note that this list assumes that you are already following a Paleo diet. All foods and beverages that should be avoided on the Paleo diet, such as grains (wheat, oats, corn, etc.), should also be avoided here. Food Groups Eat Freely May Cause Symptoms Best Avoided Bamboo shoots Beet Bok choy Carrot Cucumber (including pickles made without sugar) Dandelion greens Artichoke (fructose) Eggplant Asparagus (fructose) Endive Broccoli (fructans) Fermented vegetables (raw Cabbage (fructans) sauerkraut, or lacto- fermented vegetables) Cauliflower (polyol) Green beans Garlic (fructans) Avocado (polyol) Kale Jerusalem artichoke Brussels sprouts (fructans) (fructans) Lettuce Celery (polyol) Leeks (fructans) Olives VEGETABLES Fennel bulb (fructans) Okra (fructans) Parsnip Green peas (fructans) Onion (fructans) Sea vegetables Mushrooms (polyol) Shallots (fructans) Spinach Snow peas (fructans, Spring onion (green part polyols) only) Sugar snap peas (fructose) Sprouts and microgreens (including alfalfa and Raddichio (fructans) sunflower) Tomato sauces and tomato Summer squash (zucchini, paste (fructose, fructans) pattypan and yellow squash) Swiss chard Tomatoes (including cherry tomatoes) Winter squash (acorn, butternut, pumpkin and spaghetti squash) kresserinstitute.com 1 ! Food Groups Eat Freely May Cause Symptoms Best Avoided Banana, ripe Blueberries Grapefruit Apple (fructose and polyol) Kiwi Apricot (polyol) Lemon Cherries (fructose and Lime polyol) Banana, unripe Mandarin Mango (fructose) Longon (polyol) Melons