Marketing Opportunities for Small-Scale Organic Wine Producers in Slovenia: Proposing a Wine Cluster Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microbial and Chemical Analysis of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Chambourcin Hybrid Grapes for Potential Use in Winemaking

fermentation Article Microbial and Chemical Analysis of Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts from Chambourcin Hybrid Grapes for Potential Use in Winemaking Chun Tang Feng, Xue Du and Josephine Wee * Department of Food Science, The Pennsylvania State University, Rodney A. Erickson Food Science Building, State College, PA 16803, USA; [email protected] (C.T.F.); [email protected] (X.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-814-863-2956 Abstract: Native microorganisms present on grapes can influence final wine quality. Chambourcin is the most abundant hybrid grape grown in Pennsylvania and is more resistant to cold temperatures and fungal diseases compared to Vitis vinifera. Here, non-Saccharomyces yeasts were isolated from spontaneously fermenting Chambourcin must from three regional vineyards. Using cultured-based methods and ITS sequencing, Hanseniaspora and Pichia spp. were the most dominant genus out of 29 fungal species identified. Five strains of Hanseniaspora uvarum, H. opuntiae, Pichia kluyveri, P. kudriavzevii, and Aureobasidium pullulans were characterized for the ability to tolerate sulfite and ethanol. Hanseniaspora opuntiae PSWCC64 and P. kudriavzevii PSWCC102 can tolerate 8–10% ethanol and were able to utilize 60–80% sugars during fermentation. Laboratory scale fermentations of candidate strain into sterile Chambourcin juice allowed for analyzing compounds associated with wine flavor. Nine nonvolatile compounds were conserved in inoculated fermentations. In contrast, Hanseniaspora strains PSWCC64 and PSWCC70 were positively correlated with 2-heptanol and ionone associated to fruity and floral odor and P. kudriazevii PSWCC102 was positively correlated with a Citation: Feng, C.T.; Du, X.; Wee, J. Microbial and Chemical Analysis of group of esters and acetals associated to fruity and herbaceous aroma. -

Freyvineyards

FREY VINEYARDS BIODYNAMIC 2016 CABERNET SAUVIGNON MENDOCINO Vibrant, focused and expressive, with flavors of allspice, huckleberry and underbrush, our Cabernet mirrors the terrior of Redwood Valley’s complex ecosystem. Graceful tannins sustain a velvety mouthfeel, with subtle violet notes on the finish. Pair with New York steaks and Gorgonzola butter or wild mushroom risotto. Alcohol: 13.5% by volume. Total sulfite, naturally occurring: TTB analysis, 1ppm. Aged in stainless & exposed to French oak staves FREY VINEYARDS Pioneers of Biodynamic® & Organic Winemaking in America. No Sulfites Added Wine Since 1980. In 1996, Frey Vineyards produced the United States’ first certified Biodynamic wine. Frey Vineyards’ Biodynamic wines are made from our premium estate-grown fruit, fermented with native indigenous yeast and produced with no added sulfites. Our low impact winemaking techniques preserve and protect the terroir of the wine, highlighting the subtle flavors of the vineyard site and vintage. No cultured yeast or malolactic cultures are added. Our Biodynamic wines are never subjected to acid and sugar adjustments or flavor enhancements, upholding the authenticity of the wine. Because the wines are not manipulated to reach certain flavor profiles, each batch is unique to the fruit and farm. The result Frey Vineyards is a portfolio of wines that are pure and delicious and mirror 14000 Tomki Rd. the richness and beauty of our land. All Frey Biodynamic Redwood Valley, CA 95470 wines are estate-grown and bottled in accordance with [email protected] Demeter Biodynamic and USDA Organic regulations. FreyWine.com. -

Wine Listopens PDF File

Reservations Accepted | 10/1/2021 1 Welcome to Virginia’s First Urban Winery! What’s an Urban Winery, you ask? Well, we are. Take a look around, and you’ll see a pretty unique blend of concepts. First and foremost, you’ll see wine made here under our Mermaid label, highlighting the potential of Virginia’s grapes and wine production. Virginia has a rich history of grape growing and winemaking, and we’ve selected the best grapes we can get our hands on for our Mermaid Wines. We primarily work with fruit from our Charlottesville vineyard, with occasional sourcing from other locations if we see the opportunity to make something special. We’ve put together some really enjoyable wines for you to try – some classic, some fun, all delicious. Secondly, you’ll see wines from all around the world. Some you’ll recognize, others you might not. These selections lend to our wine bar-style atmosphere and really enrich the experience by offering a wide range of wines to be tried. They’re all available by the bottle, and most by the glass and flight as well, right alongside our Mermaid Wines. The staff can tell you all about any of them, so rest assured that you’ll never be drinking blind. These wines also rotate with the season, and there’s always something new to try. We have a full kitchen too, with a diverse menu that can carry you through lunch, brunch and dinner from the lightest snack to a full-on meal. With dishes that can be easily paired with a variety of our wines, make sure you try anything that catches your eye. -

Evaluation of the Oenological Suitability of Grapes Grown Using Biodynamic Agriculture: the Case of a Bad Vintage R

Journal of Applied Microbiology ISSN 1364-5072 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Evaluation of the oenological suitability of grapes grown using biodynamic agriculture: the case of a bad vintage R. Guzzon1, S. Gugole1, R. Zanzotti1, M. Malacarne1, R. Larcher1, C. von Wallbrunn2 and E. Mescalchin1 1 Edmund Mach Foundation, San Michele all’Adige, Italy 2 Institute for Microbiology and Biochemistry, Hochschule Geisenheim University, Geisenheim, Germany Keywords Abstract biodynamic agriculture, FT-IR, grapevine, wine microbiota, yeast. Aims: We compare the evolution of the microbiota of grapes grown following conventional or biodynamic protocols during the final stage of ripening and Correspondence wine fermentation in a year characterized by adverse climatic conditions. Raffaele Guzzon, Edmund Mach Foundation, Methods and Results: The observations were made in a vineyard subdivided Via E. Mach 1, San Michele all’Adige, Italy. into two parts, cultivated using a biodynamic and traditional approach in a E-mail: [email protected] year which saw a combination of adverse events in terms of weather, creating 2015/1999: received 11 June 2015, revised the conditions for extensive proliferation of vine pests. The biodynamic 12 November 2015 and accepted approach was severely tested, as agrochemicals were not used and vine pests were 14 November 2015 counteracted with moderate use of copper, sulphur and plant extracts and with intensive use of agronomical practices aimed at improving the health of the doi:10.1111/jam.13004 vines. Agronomic, microbiological and chemical testing showed that the response of the vineyard cultivated using a biodynamic approach was comparable or better to that of vines cultivated using the conventional method. -

1000 Best Wine Secrets Contains All the Information Novice and Experienced Wine Drinkers Need to Feel at Home Best in Any Restaurant, Home Or Vineyard

1000bestwine_fullcover 9/5/06 3:11 PM Page 1 1000 THE ESSENTIAL 1000 GUIDE FOR WINE LOVERS 10001000 Are you unsure about the appropriate way to taste wine at a restaurant? Or confused about which wine to order with best catfish? 1000 Best Wine Secrets contains all the information novice and experienced wine drinkers need to feel at home best in any restaurant, home or vineyard. wine An essential addition to any wine lover’s shelf! wine SECRETS INCLUDE: * Buying the perfect bottle of wine * Serving wine like a pro secrets * Wine tips from around the globe Become a Wine Connoisseur * Choosing the right bottle of wine for any occasion * Secrets to buying great wine secrets * Detecting faulty wine and sending it back * Insider secrets about * Understanding wine labels wines from around the world If you are tired of not know- * Serve and taste wine is a wine writer Carolyn Hammond ing the proper wine etiquette, like a pro and founder of the Wine Tribune. 1000 Best Wine Secrets is the She holds a diploma in Wine and * Pairing food and wine Spirits from the internationally rec- only book you will need to ognized Wine and Spirit Education become a wine connoisseur. Trust. As well as her expertise as a wine professional, Ms. Hammond is a seasoned journalist who has written for a number of major daily Cookbooks/ newspapers. She has contributed Bartending $12.95 U.S. UPC to Decanter, Decanter.com and $16.95 CAN Wine & Spirit International. hammond ISBN-13: 978-1-4022-0808-9 ISBN-10: 1-4022-0808-1 Carolyn EAN www.sourcebooks.com Hammond 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page i 1000 Best Wine Secrets 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page ii 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iii 1000 Best Wine Secrets CAROLYN HAMMOND 1000WineFINAL_INT 8/24/06 2:21 PM Page iv Copyright © 2006 by Carolyn Hammond Cover and internal design © 2006 by Sourcebooks, Inc. -

Slovenia Wine Stars and Hidden Treasures

Slovenia Wine Stars and Hidden Treasures Organized by Vinitaly in cooperation with Vino magazine, Slovenia Tasting Ex…Press • Vinitaly • Verona • 10 april 2017 Robert Gorjak Vino is a Slovenian magazine Robert Gorjak grew up in a winegrowing family for the lovers of wine, culinary arts near Jeruzalem in Slovenia. His passion for wine and other delights. blossomed in the early 80s when he had the It is the most well-established opportunity of observing professional sommeliers and influential medium in the field of wine at work and joining them during tastings. His first and cuisine in Slovenia. article on wine appeared in 1994. He is Slovenia’s contributor for the Jancis Robinson’s Oxford Wine Publishing: Companion and The World Atlas of Wine (Hugh 4 issues per year Johnson, Jancis Robinson). He also contributed to several editions of Hugh Johnson’s Pocket Wine First published: Book. 2003 In 2001, he set up the first Slovenian wine school Publisher: alongside his wife Sandra – the Belvin Wine School, Revija Vino, d. o. o. where he teaches and develops new programs and Dobravlje 9 runs WSET courses. SI-5263 Dobravlje Slovenia He is the first Slovenian to hold a WSET Diploma and is the author of five editions of Wine Guide – phone: 00 386 82 051 612 Slovenia, where he has been rating Slovenian mobile: 00 386 51 382 381 wines. He judges at a variety of renowned [email protected] international wine tastings including Decanter www.revija-vino.si World Wine Awards, where he was the Chairman of the Slovenian panel. -

Our Portfolio

2020 About Us Circo Vino (pronounced Chir-co Vee-no) is loosely translated as “Wine Circus” in Italian. Circo Vino serves as a national importer for the United States and is licensed to sell to wholesalers nationwide. Circo Vino acts as the main sales, marketing, and public relations entity for its winery partners. Circo Vino does not have a centralized office or warehouse, preferring to utilize a virtual office and current technology to centralize company communication. Circo Vino has significant relationships with shipping agencies and warehouses nationally and internationally that assist us in our flexible and fresh shipping design. Circo Vino began in 2009 with a dedication to find flexible avenues to encourage direct imports of artisanal wines from unique terroirs to the USA marketplace. We believe that sublime wine is a result of the collaborative relationship between mother nature, the grower and the consumer. The ultimate connection we seek to create is between the grower and those who appreciate his or her wines. With this in mind, we specialize in Direct Import Facilitation, focusing on emerging state markets that need assistance in directly importing wine as well as helping established markets simplify their Direct Import structure. We seek wines that demonstrate a sense of place and a singularity of style - wines that make us say “Yes! This is it!” We gravitate toward wines that are farmed in low-impact ways and handled gently, and we prefer to work with winery partners who grow wines with both a respect for tradition and a sustainable vision for the future. We love working with partners that infuse humor and creativity into their work and are interested in reaching the dinner tables of American wine drinkers as well as retail shelves and restaurant wine lists. -

WINE BOOK United States Portfolio

WINE BOOK United States Portfolio January, 2020 Who We Are Blue Ice is a purveyor of wines from the Balkan region with a focus on Croatian wineries. Our portfolio of wines represents small, family owned businesses, many of which are multigenerational. Rich soils, varying climates, and the extraordinary talents of dedicated artisans produce wines that are tempting and complex. Croatian Wines All our Croatian wines are 100% Croatian and each winery makes its wine from grapes grown and cultivated on their specific vineyard, whether they are the indigenous Plavac Mali, or the global Chardonnay. Our producers combine artisan growing techniques with the latest production equipment and methods, giving each wine old-world character with modern quality standards. Whether it’s one of Croatia’s 64 indigenous grape varieties, or something a bit more familiar, our multi-generational wineries all feature unique and compelling offerings. Italian Wines Our Italian wines are sourced from the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region, one of the 20 regions of Italy and one of five autonomous regions. The capital is Trieste. Friuli- Venezia Giulia is Italy’s north-easternmost region and borders Austria to the north, Slovenia to the east, and the Adriatic Sea and Croatia, more specifically Istria, to the south. Its cheeses, hams, and wines are exported not only within Europe but have become known worldwide for their quality. These world renown high-quality wines are what we are bringing to you for your enjoyment. Bosnian Wines With great pride, we present highest quality wines produced in the rocky vineyards of sun washed Herzegovina (Her-tsuh-GOH-vee-nuh), where limestone, minerals, herbs and the Mediterranean sun are infused into every drop. -

Big, Bold Red Wines Aromatic White Wines Full-Bodied

“ A meal without wine is like a day without sunshine." WINE LIST - Brillat-Savarin At the CANal RITZ, we believe that wine should be accessible, affordable and enjoyable. This diverse selection of wines has been carefully designed to complement our menu and enhance your dining experience. Fresh, Lively Red Wines Available CHEERS! S A N T É! S A LU T E! in a Pinot Noir 2017, Blanville. Languedoc, France Generous fruit and spice notes. Glass, a Rioja 2017 Cosecha, Pecina. Spain ½ Litre Fresh, juicy and unoaked Tempranillo. bottle Gamay 2018, Southbrook. Niagara VQA (organic) and a A delicious and oh so drinkable Ontario wine Full Bottle Medium-Bodied Red Wines Syrah 2017, Camas. France (organic) Light, Dry White Wines A delicious organic wine from the Limoux region in the Pinot Grigio 2018, Giusti. Veneto, Italy South of France. Refreshingly crisp with zesty citrus and mango flavours. Sangiovese 2016, Dardo. Tuscany, Italy Riesling 2017, Southbrook. Niagara VQA (organic) Juicy red berry fruit, soft and silky on the palate, plush Dry as a bone and delicious, from one of Ontario’s tannins and flavourful. leading wineries. Chianti 2016, Lanciola. Tuscany, Italy Pinot Grigio 2017, Fidora. Veneto, Italy (organic) Made with dried grapes, this “Ripasso” style wine has This certified organic wine is refreshing with a distinct plenty of ripe fruit. minerality and crisp lemon and pear finish Frappato 2016, Vino Lauria. Sicily, Italy (organic) This deliciously atypical Sicilian wine is livelier than most wines from this hot island. Aromatic White Wines Sauvignon Blanc 2018, Middle Earth. New Zealand Rosso di Montalcino 2016, Fanti. -

An Overview on Sustainability in the Wine Production Chain

beverages Review An Overview on Sustainability in the Wine Production Chain Antonietta Baiano Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie, degli Alimenti e dell’Ambiente, University of Foggia, Via Napoli, 25, 71122 Foggia, Italy; [email protected]; Tel.: +39-881-589249 Abstract: Despite the great relevance of sustainable development, the absence of a shared approach to sustainable vitiviniculture is evident. This review aimed to investigate sustainability along the entire wine chain, from primary production to the finished wine, with specific attention to three key dimensions of sustainability (environmental, social, and economic) and relating measures. Therefore, it was decided to: investigate the ways in which sustainability is applied in the various stages of the production chain (wine growing, wineries, distribution chain, and waste management); analyse the regulations in force throughout the world and the main labelling systems; provide numerical information on sustainable grapes and wines; study the objective quality of sustainable wines and that perceived by consumers, considering that it affects their willingness to pay. The research highlighted that rules and regulations on organic production of grapes and wines are flanked by several certification schemes and labelling systems. Although sustainable wines represent a niche in the market, in recent years, there has been an increase in vineyards conducted with sustainable (mainly organic and biodynamic) methods, and a consequent increase in the production of sustainable wines both in traditional and emerging producing countries. Although (or perhaps precisely for this reason) no significant differences in quality are found among sustainable and conventional wines, consumers are willing to pay a premium for sustainably produced wines. This finding should encourage wineries to both put in place environmental activities and intensify their communication. -

BIWC Entryform-2021-2021-7-2 Copy

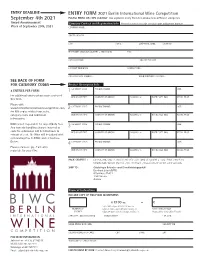

ENTRY DEADLINE ENTRY FORM 2021 Berlin International Wine Competition September 4th 2021 PLEASE PRINT OR TYPE CLEARLY Use separate entry form for products in different categories Award Announcement Company Contact and Registration Info Please be sure to include contact name and phone number Week of September 20th, 2021 COMPANY NAME: STREET ADDRESS: CITY: STATE: ZIP/POSTAL CODE: COUNTRY: TELEPHONE: (INCLUDE COUNTRY + AREA CODE) FAX: CONTACT NAME: TITLE OR POSITION: CONTACT TELEPHONE: CONTACT CELL: CONTACT EMAIL ADDRESS: MAIN CORPORATE WEBSITE: SEE BACK OF FORM FOR CATEGORY CODES Product Description Info CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: 4 ENTRIES PER FORM 1 For additional entries please make copies of REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE this form. Please visit: www.berlininternationalwinecompetition.com 2 CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: for PDF copies of this form, rules, category codes and additional REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE information. BIWC is not responsible for import/duty fees. CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: Any material handling charges incurred as 3 costs for submission will be billed back to REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE entrant at cost. No Wine will be judged with outstanding fees to BIWC and or Customs Broker. 4 CATEGORY CODE: PRODUCT NAME: AGE: Please retain a copy of all entry materials for your files. REGION OR TYPE: COUNTRY OF ORIGIN: ALCOHOL %: BOTTLE SIZE (ML) RETAIL PRICE PACK SAMPLES : (3) 750, 700, 500, or 333ml bottles for each entry along with a copy of this entry form. -

Ribera Del Duero 16 - Marqués De Murrieta 70 43 Marqués De Riscal 79 Alejandro Fernández 17 -20 Montecillo 71~72

Columbia Restaurant & the Gonzmart Family’s Wine Philosophy At the Columbia Restaurant we believe the relationship of wine and food is an essential part of the dining experience and that two aspects of elegant dining deserve specialized attention: The preparation and serving of the cuisine and the selection of the finest wines and stemware to accompany it. In keeping with our tradition of serving the most elegant Spanish dishes, we have chosen to feature a collection of Spain's finest wines and a selection of American wines, sparkling whites and Champagne. Our wines are stored in our wine cellar in a climate controlled environment at 55° Fahrenheit with 70% humidity. The Columbia Restaurant’s wine list represents 4th and 5th generation, owner and operators, Richard and Andrea Gonzmart’s lifetime involvement in their family’s business. Their passion for providing guests the best wines from Spain, as well as their personal favorites from California, are reflected in every selection. They believe wines should be affordable and represent great value. Columbia Restaurant's variety of wines illustrates the depth of knowledge and concern the Gonzmart family possesses, by keeping abreast of the wine market in the United States and by traveling to Spain. This is all done for the enjoyment of our guests. We are confident that you will find the perfect wine to make your meal a memorable one. Ybor January 2019 Table of Contents Complete Overview Wines of Spain 5- 132 Understanding a Spanish Wine Label 6 Map of Spain with Wine Regions How to Read a Spanish Wine Label 7 Wines of Spain 8 - 132 Wines of California 133 - 182 Other Wines from the United States 183-185 Wines of South America 186- 195 Wine of Chile 187 - 190 Wines of Argentina 191 - 194 Cava, Sparkling & Champagne 196-198 Dessert Wines 199-200 Small Bottles 201 - 203 Big Bottles 203 - 212 Magnums - 1 .