THE HIDDEN WEALTH of CITIES Creating, Financing, and Managing Public Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Get to Singapore Nursing Board by Public Transport (81 Kim Keat Road, #08-00, Singapore 328836)

How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by Public Transport (81 Kim Keat Road, #08-00, Singapore 328836) Bus Stop Number: 52411 (Blk 105 ) Bus Stop Number: 52499 (St. Michael Bus Terminal ) Jalan Rajah (After Global Indian International School) Whampoa Road Bus services : 139, 565 Bus Services : 21, 124, 125, 131, 186 Bus Stop Number: 52419 (Curtin S’pore ) Bus Stop Number: 52099 (Opp. NKF) Jalan Rajah Kim Keat Road Bus Services : 139 Bus Services : 21, 124, 125, 131, 139, 186, 565 How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Nearest MRT Station How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Toa Payoh Alight at NS19 – Toa Payoh MRT Station (Use Exit B) MRT Station Take Bus 139 at Toa Payoh Bus Interchange (52009) (NS19) Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52411 (Blk 105) – Jalan Rajah Number of Stops: 5 Walk towards NKF Centre (200m away) OR Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52099 (opp. NKF) –Kim Keat Road Number of Stops: 9 Cross the road and walk towards NKF Centre (50m away) Novena MRT Alight at NS20 – Novena MRT Station (Use Exit B2) How to get to SNB (Public Transport) 1 June 2011 Page 1 of 4 Nearest MRT Station How to get to Singapore Nursing Board by MRT and Bus Station Walk down towards Novena Church. (NS20) Walk across the overhead bridge, and walk towards Bus Stop Number: 50031 – Thomson Road (in front of Novena Ville). Take Bus 21 or 131 Alight at Bus Stop Number: 52499 (St. Michael Bus Terminal) –Whampoa Road Number of Stops: 10 Walk towards NKF Centre (110m away) Newton MRT Alight at NS21 – Newton MRT Station (Use Exit A) Station Take Bus 124 at Bus Stop Number: 40181 – Scotts Road (heading towards Newton (NS21) Road). -

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial Occupiers

FITTING-OUT MANUAL for Commercial Occupiers SMRT PROPERTIES SMRT Investments Pte Ltd 251 North Bridge Road Singapore 179102 Tel : 65 6331 1000 Fax : 65 6337 5110 www.smrt.com.sg While every reasonable care has been taken to provide the information in this Fitting-Out Manual, we make no representation whatsoever on the accuracy of the information contained which is subject to change without prior notice. We reserve the right to make amendments to this Fitting-Out Manual from time to time as necessary. We accept no responsibility and/or liability whatsoever for any reliance on the information herein and/or damage howsoever occasioned. 09/2013 (Ver 3.9) Fitting Out Manual SMRT Properties To our Valued Customer, a warm welcome to you! This Fitting-Out Manual is specially prepared for you, our Valued Customer, to provide general guidelines for you, your appointed consultants and contractors when fitting-out your premises at any of our Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) or Light Rail Transit (LRT) stations. This Fitting-Out Manual serves as a guide only. Your proposed plans and works will be subjected to the approval of SMRT and the relevant authorities. We strongly encourage you to read this document before you plan your fitting-out works. Do share this document with your consultants and contractors. While reasonable care has been taken to prepare this Fitting-Out Manual, we reserve the right to amend its contents from time to time without prior notice. If you have any questions, please feel free to approach any of our Management staff. We will be pleased to assist you. -

It's Not Just a Credit Card It's Reserving the Best For

L14457 88925 Gourmet 07 new 4/23/07 6:26 PM Page 6 It’s not just a credit card It’s reserving the best for you Composite L14457 88925 Gourmet 07 new 4/23/07 6:26 PM Page 2 Exclusive dining privileges await at nearly every turn! Now serving… It’s time to please your palate to the hilt with the long list of perks • Asian that Citibank has brought you! You can indulge in your love of good • Café & Delights food with some very exclusive privileges at a wide selection of dining • Chill-Out outlets in Singapore. In particular, you can enjoy the exclusivity of being the only cardmembers around to receive discounts at Jumbo • International Seafood Restaurant, Café Cartel, Fish&Co., Lerk Thai Restaurant, • Western the coffee connoisseur (tcc), Velvet and Wine Bar. Go on, plan your • Directory List meals with this discount and privileges directory now! Composite L14457 88925 Gourmet 07 new 4/23/07 6:26 PM Page 7 Ah Hoi's Kitchen Bayang (Balinese) • 15% off total à la carte • 10% off total bill food bill 3A Clarke Quay #01-05 Traders Hotel Singapore Poolside Tel: 6337 0144. Level 4 Tel: 6831 4373 Offer is valid from now till 31 August 2007. Al Hamra Lebanese & Beads Restaurant & Lounge Middle Eastern Cuisine • 20% off à la carte Thai buffet • 15% off à la carte food menu Grand Mercure Roxy Hotel, 23 Lorong Mambong, Holland Village Tel: 6464 8488 50 East Coast Road, Level 2 Tel : 6340 5678 Ambrosia Café Offer is valid from now till 31 March 2008. -

Hillside Address City Living One of the Best Locations for a Residence Is by a Hill

Hillside Address City Living One of the best locations for a residence is by a hill. Here, you can admire the entire landscape which reveals itself in full glory and splendour. Living by the hill – a privilege reserved for the discerning few, is now home. Artist’s Impression • Low density development with large land size. • Smart home system includes mobile access smart home hub, smart aircon control, smart gateway with • Well connected via major arterial roads and camera, WIFI doorbell with camera and voice control expressways such as West Coast Highway and system and Yale digital lockset. Ayer Rajah Expressway. Pasir Panjang • International schools in the vicinity are United World College (Dover), Nexus International School, Tanglin Trust School and The Japanese School (Primary). • Pasir Panjang MRT station and Food Centre are within walking distance. • Established schools nearby include Anglo-Chinese School (Independent), Fairfield Methodist School and Nan Hua Primary School. • With the current URA guideline of 100sqm ruling in • Branded appliances & fittings from Gaggenau, the Pasir Panjang area, there will be a shortage of Bosch, Grohe and Electrolux. smaller units in the future. The master plan for future success 1 St James Power Station to be 2 Housing complexes among the greenery and A NUS and NUH water sports and leisure options. Island Southern Gateway of Asia served only by autonomous electric vehicles. B Science Park 3 Waterfront area with mixed use developments and C Mapletree Business City new tourist attractions, serves as extension of the Imagine a prime waterfront site, three times the size of Marina Bay. That is the central business district with a high-tech hub for untold potential of Singapore’s Master Plan for the Greater Southern Waterfront. -

Best Hidden Gems in Singapore"

"Best Hidden Gems in Singapore" Created by: Cityseeker 17 Locations Bookmarked Singapore Philatelic Museum "Interesting Exhibits" Ever wondered how that stamp in the corner of your envelope was made? Well, that is precisely what you will learn at South-east Asia's first philatelic museum. Opened in 1995, this museum holds an extensive collection of local and international stamps dating back to the 19th century. Anything related to stamps can be found here like first day by Tanya Procyshyn covers, artwork, printing proofs, progressive sheets, even a number of private collections. Equipped with interactive exhibits, audio-visual facilities, a resource center and games, visitors are likely to come away with a new-found interest in stamp collecting. +65 6337 3888 www.spm.org.sg/ [email protected] 23-B Coleman Street, g Singapore Acid Bar "A Secluded Music Cove" Acid Bar occupies a small section of bar Peranakan Place, however do not be deceived by the modest size of this place. The bar is an intimate escape from the hustle of the city life. Illuminated in warm lights and neatly furnished with quaint seating spaces, Acid Bar is the place to enjoy refined drinks while soaking in acoustic tunes. A venue for memorable by Public Domain performances by local artists and bands, Acid Bar is a true hidden gem of the city that is high on nightlife vigor. +65 6738 8828 peranakanplace.com/outle [email protected] 180 Orchard Road, t/acidbar/ m Peranakan Place, Singapore Keepers "Singapore's Shopping Hub" Keepers is a shopping hub, located on Orchard Road. -

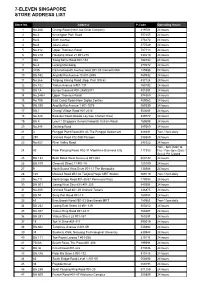

SLIDE Store Listing- 1 Apr 2019

7-ELEVEN SINGAPORE STORE ADDRESS LIST Store No. Address P.Code Operating Hours 1 No.38A Changi Road (Near Joo Chiat Complex) 419701 24 hours 2 No.3 Kensington Park Road 557255 24 hours 3 No.6 Sixth Avenue 276472 24 hours 4 No.6 Jalan Leban 577549 24 hours 5 No.912 Upper Thomson Road 787113 24 hours 6 Blk.210 Hougang Street 21 #01-275 530210 24 hours 7 302 Tiong Bahru Road #01-152 168732 24 hours 8 No.4 Lorong Mambong 277672 24 hours 9 3155 Commonwealth Avenue West #01-03 Clementi Mall 129588 24 hours 10 Blk.532 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 10 #01-2455 560532 24 hours 11 No.366 Tanjong Katong Road (Opp. Post Office) 437124 24 hours 12 Blk.102 Yishun Avenue 5 #01-137 760102 24 hours 13 Blk.1A Eunos Crescent #01-2469/2471 401001 24 hours 14 No.244H Upper Thomson Road 574369 24 hours 15 No.705 East Coast Road (Near Siglap Centre) 459062 24 hours 16 Blk.339 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1 #01-1579 560339 24 hours 17 Blk.1 Changi Village Road #01-2014 500001 24 hours 18 No.340 Balestier Road (beside Loy Kee Chicken Rice) 329772 24 hours 19 Blk 4 Level 1 Singapore General Hospital Outram Road 169608 24 hours 20 No.348 Geylang Road 389369 24 hours 21 3 Punggol Point Road #01-06 The Punggol Settlement 828694 7am-11pm daily 22 290 Orchard Road #02-08B Paragon 238859 24 hours 23 No.423 River Valley Road 248322 24 hours 7am - 8pm (Mon to 24 40 Pasir Panjang Road, #02-31 Mapletree Business City 117383 Fri) / 7am-3pm (Sat) / Sun & PH Closed 25 Blk.132 Bukit Batok West Avenue 6 #01-304 650132 24 hours 26 Blk.109 Clementi Street 11 #01-15 120109 24 hours 27 9 North Buona Vista -

Singapore for Families Asia Pacificguides™

™ Asia Pacific Guides Singapore for Families A guide to the city's top family attractions and activities Click here to view all our FREE travel eBooks of Singapore, Hong Kong, Macau and Bangkok Introduction Singapore is Southeast Asia's most popular city destination and a great city for families with kids, boasting a wide range of attractions and activities that can be enjoyed by kids and teenagers of all ages. This mini-guide will take you to Singapore's best and most popular family attractions, so you can easily plan your itinerary without having to waste precious holiday time. Index 1. The Singapore River 2 2. The City Centre 3 3. Marina Bay 5 4. Chinatown 7 5. Little India, Kampong Glam (Arab Street) and Bugis 8 6. East Coast 9 7. Changi and Pasir Ris 9 8. Central and North Singapore 10 9. Jurong BirdPark, Chinese Gardens and West Singapore 15 10. Pulau Ubin and the islands of Singapore 18 11. Sentosa, Universal Studios Singapore and "Resorts World" 21 12. Other attractions and activities 25 Rating: = Not bad = Worth trying = A real must try Copyright © 2012 Asia-Pacific Guides Ltd. All rights reserved. 1 Attractions and activities around the Singapore River Name and details What is there to be seen How to get there and what to see next Asian Civilisations Museum As its name suggests, this fantastic Address: 1 Empress Place museum displays the cultures of Asia's Rating: tribes and nations, with emphasis on From Raffles Place MRT Station: Take Exit those groups that actually built the H to Bonham Street and walk to the river Tuesday – Sunday : 9am-7pm (till city-state. -

Staging 'Peranakan-Ness': a Cultural History of the Gunong Sayang

Staging ‘Peranakan-ness’: A Cultural History of the Gunong Sayang Association’s wayang Peranakan, 1985-95 Brandon Albert Lim B.A. Hons (NUS) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History National University of Singapore Academic Year 2010/2011 Gharry and palanquin are silent, the narrow street describes decades of ash and earth. Here in the good old days the Babas paved a legend on the landscape, and sang their part – God save the King – in trembling voices. Till the Great Wars came and the glory went, and the memories grave as a museum. Ah, if only our children on the prestige of their pedigree would emulate their fathers, blaze another myth across the teasing wilderness of this Golden Peninsula. Ee Tiang Hong, Tranquerah (1985) ! i! Preface and Acknowledgements ! This is a story that weaves together many narratives. First, it is a story of how members of a specific Peranakan organisation gathered annually to stage a theatrical production showcasing aspects of their culture. It is also a story of an endeavour to resuscitate the Peranakan community’s flagging fortunes and combat an increasing apathy among its young – which by the 1980s had become leitmotifs defining the state of the community; Ee Tiang Hong’s poem on the previous page is hence an appropriate epigraph. This thesis further tells a story about an iconic performance art situated, and intertwined, within a larger narrative of 1980s Singapore socio-political realities; how did it depict the Peranakan cultural heritage while at the same time adapting its presentation to fit the context? Who was involved in the production, what were the challenges its scriptwriters and directors faced and how did its audience respond to the performance? These are but some questions we will address as the story unfolds. -

View a Portfolio of Halide Pictures, to Which

The Entity Halide Pictures is not just a production house. We represent a network of producers, directors and technical crews who brings with them years of experience in the media industry from corporate videos to feature film productions, bond together to create a common goal. A place where ideas are shared and dreams are realised. No project is too big or too small. Itʼs the stories that we created matters. Through the years, Halide Pictures have produced various project, which ranges from music videos, concerts, commercials/promos, corporate videos and short films. A recent addition to our portfolio of work, which we have completed is our first 3D Stereoscopic short film with the support of MDA and collaboration with ITE College East. With more film projects in development, we strive to bring to local audience films that has substance, films that will make a different, films that the world will be interested to watch. The Team Producers MIKE CHEW CHRISTINA CHOO Directors MiKE CHEW CHRISTINA CHOO RANDY ANG LAWRENCE ONG JEEVAN NATHAN Directors of Photography KEN MINEHAN BERNARD TAN ELGIN QUEK Portfolio Guiness “The Penguin March” – Event Coverage A series of street stingers of a group of eight, larger than life sized penguins (men dressed in penguin suits) parade the streets, to promote to the public about the new release of Guiness Draught. Shot and documented via photographic stills and video, with highlights cut into a teaser and highlights clip, showcased on the online Marketing Magazine and Life section of the Straits Times. Shot over four nights in the months of December 2007 and January 2008, the Penguins March captured the hearts of passersby from shopping malls along the streets of Orchard road, Somerset road, Peranakan place, through the festive times and Christmas decorations and frequent pub goers of Boat quay, Clark quay and various Irish pubs around the island. -

Orchard Heritage Trail Booklet

1 CONTENTS Orchard Road: From Nutmeg Orchards to Urban Jungle 2 The Origins of Orchard Road 3 Physical landscape From Orchard to Garden 6 Gambier plantations Nutmeg orchards Singapore Botanic Gardens Green spaces at Orchard Road At Home at Orchard Road 22 Early activities along Orchard Road A residential suburb Home to the diplomatic community The Istana Conserved neighbourhoods Schools and youth organisations Community service organisations Landmarks of faith Social clubs Orchard Road at War 48 Life on Orchard Road 50 Before the shopping malls MacDonald House Early entrepreneurs of Orchard Road Retail from the 1970s Screening at Orchard Road Music and nightclubs at Orchard Road Dining on the street Courting tourists to Singapore A youth hub Selected Bibliography 74 Credits 77 Suggested Short Trail Routes 78 Orchard Road’s historical gems Communities and cemeteries From orchard to garden Heritage Trail Map 81 2 3 ORCHARD ROAD: THE ORIGINS OF FROM NUTMEG ORCHARDS ORCHARD ROAD TO URBAN JUNGLE he earliest records of Orchard Road can Leng Pa Sat Koi or “Tanglin Market Street” be found in maps from the late 1820s in Hokkien after a market that once stood Twhich depicted an unnamed road that between Cuppage Road and Koek Road (near began at a point between Government Hill present-day The Centrepoint). (now Fort Canning Park) and Mount Sophia, and continued north-west towards Tanglin. Tamils used the name Vairakimadam or The name Orchard Road appeared in a map “Ascetic’s Place” for the section of Orchard drawn by John Turnbull Thomson in 1844 Road closer to Dhoby Ghaut. -

2020 MICE Directory

2020 MICE Directory EMPOWERING COMMERCE, CAPABILTIES, COMMUNITY CONTENTS MESSAGES 5 Message from SACEOS President 6 Message from Singapore Tourism Board EVENT CALENDARS 28 Calendar of Conferences 2020 31 Calendar of Exhibitions 2020 36 Calendar of Conferences 2021 38 Calendar of Exhibitions 2021 VENUE 44 Auditorium, Conventions & Exhibitions Centres 57 Hotels 69 Unique Venues DIRECTORY LISTING 81 SACEOS Members Listings 116 General Listings 209 Singapore Statutory Boards & Government Agencies 217 Advertiser’s Index SACEOS DIRECTORY 2020 Message from SACEOS President I Message from Singapore Tourism Board MR ALOYSIUS ARLANDO MS MELISSA OW President Singapore Association of Deputy Chief Executive Convention & Exhibition Singapore Tourism Board Organisers & Suppliers (SACEOS) Welcome to the 2020 edition of MICE e-directory – the industry’s go-to guide. SACEOS is a community-based association of the MICE industry whose members contribute to a rich history of successful corporate events, business meetings and conventions and exhibitions in Singapore. 2019 was another exciting year for Singapore’s business events landscape. The city maintains its momentum as a leading global business events hub, This year in 2020, SACEOS rang in the new decade with a big bang - by unveiling our brand playing host to a vibrant array of business events across various industry PRESIDENT new visual identity, a symbol of transformation, and a timely reflection that represents a hallmark clusters, and keeping its position as Asia Pacific’s leading city in the 2018 for the next phase of our growth, our hope, our unified future. global ranking by the International Congress and Convention Association MESSAGE (ICCA), and top international meeting country since 2013 in the Union of Singapore is a key player in the ASEAN region and the rest of the world. -

KHABAIR KHABAIR Facebook: Gunong Sayang Association Baba Heath Yeo Had Once Described This Form of Free-Motion Embroidery As -Ther Apeutic

Ketak ketik KHABAIR KHABAIR www.gsa.org.sg facebook: Gunong Sayang Association Baba Heath Yeo had once described this form of free-motion embroidery as ther- apeutic. To the uninitiated, like me, it had seemed like a walk in the park. You DECEMBER 2016 ISSUE 3/2016-2018 shopped for a nice piece of Swiss Voile, cut the cloth, chose patterns, selected colours of thread to be used and just got Dear members, on with it! However, I have since been educated and am no longer ignorant of the fact that the traditional art of Kita di Gunong Sayang banyak hua hee mo sampay kan khabair nia baik. Gunong Sayang Association ada Sulam is nothing short of a work of art. Clubhouse baru kat Joo Chiat! New Clubhouse la! Meh! Kita ramay-ramay buat lau jiat kat Club baru kita! After The late Mdm Moi, mentor and teacher to about two decades at Geylang Lorong 24A, we will now be at 80 Joo Chiat Place. Conveniently situated in the Heath had passed down the love for this method of kebaya embroidery to one who truly stayed heart of Katong and where many of my favourite – and I’m not alone here, I’m sure- eateries are but a stone’s faithful to the form. Hence, if you got Heath to design and sew you a kebaya, it must not be a throw away. It was a dream of the Management Committee to make that change for some months now. That “rush-job”. dream is now a reality but we are not alone in our endeavours.