Success Strategies of Elite First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Athletes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ready Toice! Hit

FALL 2019 THEReady ToICE! Hit JAY BOUWMEESTER INTEGRAL TO BLUES STANLEY CUP WIN Louie & jake debrusk A mutual admiration for each other's game INSIDE What’s INSIDEMESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT HOCKEY EDMONTON 5. OF HOCKEY EDMONTON 20. SUBWAY PARTNERSHIP MESSAGE FROM THE PUBLISHER 7. OF THE HOCKEY MAGAZINE 21. THE REF COST US THE GAME MALE MIDGET AAA EXCITING CHANGES OCCURING JAY BOUWMEESTER 8. IN EDMONTON INTEGRAL TO BLUE’S STANLEY 23. CUP VICTORY IN JUNE, 2019 EDMONTON OILERS 2ND SHIFT PROGRAM 10. BOSTON PIZZA RON BRODEUR SCHOLARSHIP AWARD FEATURED ON THE COVER 26. 13. NICOLAS GRMEK HOCKEY NIGHT IN CANADA LOUIE & JAKE DEBRUSK 30. IN CREE FATHER & SON - A MUTUAL 14. ADMIRATION FOR EACH OTHER’S GAME SPOTLIGHT ON AN OFFICIAL BRETT ROBBINS EDMONTON ARENA 32. 18. LOCATOR MAP Message From Hockey Edmonton 10618- 124 Street Edmonton, AB T5N 1S3 Ph: (780) 413-3498 • Fax: (780) 440-6475 www.hockeyedmonton.ca Welcome back! I hope you had a chance to get away with your family To contact any of the Executive or Standing and friends to enjoy summer somewhere that was hot and warm. Committees, please visit our website It’s amazing how time speeds by. It feels like just yesterday we were dropping the puck at the ENMAX Hockey Edmonton Championships and going into our annual general meeting where I became president HOCKEY EDMONTON | EXECUTIVES of Hockey Edmonton. Fast forward to now when player evaluations President: Joe Spatafora and team selections have ended and we are into our players’ first practices, league games, tournaments and team building events. -

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup

1988-1989 Panini Hockey Stickers Page 1 of 3 1 Road to the Cup Calgary Flames Edmonton Oilers St. Louis Blues 2 Flames logo 50 Oilers logo 98 Blues logo 3 Flames uniform 51 Oilers uniform 99 Blues uniform 4 Mike Vernon 52 Grant Fuhr 100 Greg Millen 5 Al MacInnis 53 Charlie Huddy 101 Brian Benning 6 Brad McCrimmon 54 Kevin Lowe 102 Gordie Roberts 7 Gary Suter 55 Steve Smith 103 Gino Cavallini 8 Mike Bullard 56 Jeff Beukeboom 104 Bernie Federko 9 Hakan Loob 57 Glenn Anderson 105 Doug Gilmour 10 Lanny McDonald 58 Wayne Gretzky 106 Tony Hrkac 11 Joe Mullen 59 Jari Kurri 107 Brett Hull 12 Joe Nieuwendyk 60 Craig MacTavish 108 Mark Hunter 13 Joel Otto 61 Mark Messier 109 Tony McKegney 14 Jim Peplinski 62 Craig Simpson 110 Rick Meagher 15 Gary Roberts 63 Esa Tikkanen 111 Brian Sutter 16 Flames team photo (left) 64 Oilers team photo (left) 112 Blues team photo (left) 17 Flames team photo (right) 65 Oilers team photo (right) 113 Blues team photo (right) Chicago Blackhawks Los Angeles Kings Toronto Maple Leafs 18 Blackhawks logo 66 Kings logo 114 Maple Leafs logo 19 Blackhawks uniform 67 Kings uniform 115 Maple Leafs uniform 20 Bob Mason 68 Glenn Healy 116 Alan Bester 21 Darren Pang 69 Rolie Melanson 117 Ken Wregget 22 Bob Murray 70 Steve Duchense 118 Al Iafrate 23 Gary Nylund 71 Tom Laidlaw 119 Luke Richardson 24 Doug Wilson 72 Jay Wells 120 Borje Salming 25 Dirk Graham 73 Mike Allison 121 Wendel Clark 26 Steve Larmer 74 Bobby Carpenter 122 Russ Courtnall 27 Troy Murray -

Vancouver Canucks 2009 Playoff Guide

VANCOUVER CANUCKS 2009 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS VANCOUVER CANUCKS TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory . .3 Vancouver Canucks Playoff Schedule. 4 General Motors Place Media Information. 5 800 Griffiths Way CANUCKS EXECUTIVE Vancouver, British Columbia Chris Zimmerman, Victor de Bonis. 6 Canada V6B 6G1 Mike Gillis, Laurence Gilman, Tel: (604) 899-4600 Lorne Henning . .7 Stan Smyl, Dave Gagner, Ron Delorme. .8 Fax: (604) 899-4640 Website: www.canucks.com COACHING STAFF Media Relations Secured Site: Canucks.com/mediarelations Alain Vigneault, Rick Bowness. 9 Rink Dimensions. 200 Feet by 85 Feet Ryan Walter, Darryl Williams, Club Colours. Blue, White, and Green Ian Clark, Roger Takahashi. 10 Seating Capacity. 18,630 THE PLAYERS Minor League Affiliation. Manitoba Moose (AHL), Victoria Salmon Kings (ECHL) Canucks Playoff Roster . 11 Radio Affiliation. .Team 1040 Steve Bernier. .12 Television Affiliation. .Rogers Sportsnet (channel 22) Kevin Bieksa. 14 Media Relations Hotline. (604) 899-4995 Alex Burrows . .16 Rob Davison. 18 Media Relations Fax. .(604) 899-4640 Pavol Demitra. .20 Ticket Info & Customer Service. .(604) 899-4625 Alexander Edler . .22 Automated Information Line . .(604) 899-4600 Jannik Hansen. .24 Darcy Hordichuk. 26 Ryan Johnson. .28 Ryan Kesler . .30 Jason LaBarbera . .32 Roberto Luongo . 34 Willie Mitchell. 36 Shane O’Brien. .38 Mattias Ohlund. .40 Taylor Pyatt. .42 Mason Raymond. 44 Rick Rypien . .46 Sami Salo. .48 Daniel Sedin. 50 Henrik Sedin. 52 Mats Sundin. 54 Ossi Vaananen. 56 Kyle Wellwood. .58 PLAYERS IN THE SYSTEM. .60 CANUCKS SEASON IN REVIEW 2008.09 Final Team Scoring. .64 2008.09 Injury/Transactions. .65 2008.09 Game Notes. 66 2008.09 Schedule & Results. -

1989-90 O-Pee-Chee Hockey Card Set Checklist

1 989-90 O-PEE-CHEE HOCKEY CARD SET CHECKLI ST 1 Mario Lemieux 2 Ulf Dahlen 3 Terry Carkner RC 4 Tony McKegney 5 Denis Savard 6 Derek King RC 7 Lanny McDonald 8 John Tonelli 9 Tom Kurvers 10 Dave Archibald 11 Peter Sidorkiewicz RC 12 Esa Tikkanen 13 Dave Barr 14 Brent Sutter 15 Cam Neely 16 Calle Johansson RC 17 Patrick Roy 18 Dale DeGray RC 19 Phil Bourque RC 20 Kevin Dineen 21 Mike Bullard 22 Gary Leeman 23 Greg Stefan 24 Brian Mullen 25 Pierre Turgeon 26 Bob Rouse RC 27 Peter Zezel 28 Jeff Brown 29 Andy Brickley RC 30 Mike Gartner 31 Darren Pang 32 Pat Verbeek 33 Petri Skriko 34 Tom Laidlaw 35 Randy Wood 36 Tom Barrasso 37 John Tucker 38 Andrew McBain 39 David Shaw 40 Reggie Lemelin 41 Dino Ciccarelli 42 Jeff Sharples Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jari Kurri 44 Murray Craven 45 Cliff Ronning RC 46 Dave Babych 47 Bernie Nicholls 48 Jon Casey RC 49 Al MacInnis 50 Bob Errey RC 51 Glen Wesley 52 Dirk Graham 53 Guy Carbonneau 54 Tomas Sandstrom 55 Rod Langway 56 Patrik Sundstrom 57 Michel Goulet 58 Dave Taylor 59 Phil Housley 60 Pat LaFontaine 61 Kirk McLean RC 62 Ken Linseman 63 Randy Cunneyworth 64 Tony Hrkac 65 Mark Messier 66 Carey Wilson 67 Steve Leach RC 68 Christian Ruuttu 69 Dave Ellett 70 Ray Ferraro 71 Colin Patterson RC 72 Tim Kerr 73 Bob Joyce 74 Doug Gilmour 75 Lee Norwood 76 Dale Hunter 77 Jim Johnson 78 Mike Foligno 79 Al Iafrate 80 Rick Tocchet 81 Greg Hawgood RC 82 Steve Thomas 83 Steve Yzerman 84 Mike McPhee 85 David Volek RC 86 Brian Benning 87 Neal Broten 88 Luc Robitaille 89 Trevor Linden RC Compliments -

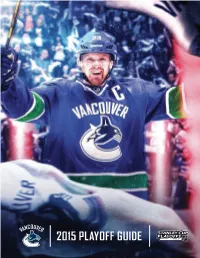

2015 Playoff Guide Table of Contents

2015 PLAYOFF GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Company Directory ......................................................2 Brad Richardson. 60 Luca Sbisa ..............................................................62 PLAYOFF SCHEDULE ..................................................4 Daniel Sedin ............................................................ 64 MEDIA INFORMATION. 5 Henrik Sedin ............................................................ 66 Ryan Stanton ........................................................... 68 CANUCKS HOCKEY OPS EXECUTIVE Chris Tanev . 70 Trevor Linden, Jim Benning ................................................6 Linden Vey .............................................................72 Victor de Bonis, Laurence Gilman, Lorne Henning, Stan Smyl, Radim Vrbata ...........................................................74 John Weisbrod, TC Carling, Eric Crawford, Ron Delorme, Thomas Gradin . 7 Yannick Weber. 76 Jonathan Wall, Dan Cloutier, Ryan Johnson, Dr. Mike Wilkinson, Players in the System ....................................................78 Roger Takahashi, Eric Reneghan. 8 2014.15 Canucks Prospects Scoring ........................................ 84 COACHING STAFF Willie Desjardins .........................................................9 OPPONENTS Doug Lidster, Glen Gulutzan, Perry Pearn, Chicago Blackhawks ..................................................... 85 Roland Melanson, Ben Cooper, Glenn Carnegie. 10 St. Louis Blues .......................................................... 86 Anaheim Ducks -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 4/3/2020 Anaheim Ducks Edmonton Oilers 1182049 Ducks owners agree to pay arena workers’ salaries 1182078 COVID-19 isolation means dog days for Edmonton Oilers' through June Ryan Nugent-Hopkins 1182050 Ducks owners to continue to pay part-time employees 1182079 Lowetide: Making the call on RFA and UFA players on the through June 30 Oilers’ 50-man roster 1182051 Ducks owners extending financial support of arena, other business employees Montreal Canadiens 1182080 In his goal crease, Canadiens prospect Michael McNiven Arizona Coyotes found a sanctuary from pain 1182052 Season pause affording Arizona Coyotes center Derek Stepan more time with family New Jersey Devils 1182053 AZ alone: Conor Garland’s personal loss, concern for 1182081 Scouting Devils’ 2019 draft class: Arseny Gritsyuk ‘has girlfriend, on-ice regrets elements’ in his game to establish space and bury chan Boston Bruins New York Islanders 1182054 Milan Lucic joined Instagram, and Bruins' fans will love his 1182082 Islanders’ Jordan Eberle sees unique hurdle for an NHL first post coronavirus return 1182055 Brian Burke reveals what Ducks would've given Bruins for 1182083 Islanders players pool funds to donate N95 masks to Joe Thornton in 2005 Northwell Health 1182056 Brad Marchand, Patrice Bergeron, Zdeno Chara lead NHL 1182084 Islanders president Lou Lamoriello 'extremely optimistic' in plus-minus this decade NHL season will resume 1182057 Bruins prospect Jeremy Swayman named Hobey Baker 1182085 Islanders' Jordan Eberle knows time is running out to -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK X DAN Lacouture, DAN KECZMER, JACK CARLSON, RICHARD BRENNAN, BRAD MA

Case 1:14-cv-02531-SAS Document 4 Filed 04/11/14 Page 1 of 116 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK x DAN LaCOUTURE, DAN KECZMER, JACK : Civil Action No. 1:14-cv-02531-SAS CARLSON, RICHARD BRENNAN, BRAD : MAXWELL, MICHAEL PELUSO, TOM : [CORRECTED] CLASS ACTION YOUNGHANS, ALLAN ROURKE, and : COMPLAINT SCOTT BAILEY, Individually and on Behalf : of All Others Similarly Situated, : : Plaintiffs, : : vs. : : NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE, : : Defendant. : : x JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Case 1:14-cv-02531-SAS Document 4 Filed 04/11/14 Page 2 of 116 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ..........................................................................................5 III. THE PARTIES.....................................................................................................................5 IV. SUBSTANTIVE ALLEGATIONS .....................................................................................9 A. The Origins of the NHL ...........................................................................................9 B. The NHL Quickly Establishes Its Roots in Extreme Violence ..............................11 1. The Coutu Incidents ...................................................................................12 2. The Cleghorn Incidents ..............................................................................13 3. The Richard Incident..................................................................................14 -

NHL94 Manual for Gens

• BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • HOCKEY • • HOCKEY • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY • FOOTBALL • BASKETBALL • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY FOOTBALL BYLINE USA Ron Barr, sports anchor, EA SPORTS Emmy Award-winning reporter Ron Barr brings over 20 years of professional sportscasting experience to EA SPORTS. His network radio and television credits include play-by play and color commentary for the NBA, NFL and the Olympic Games. In addition to covering EA SPORTS sporting events, Ron hosts Sports Byline USA, the premiere sports talk radio show broadcast over 100 U.S. stations and around the world on Armed Forces Radio Network and* Radio New Zealand. Barr’s unmatched sports knowledge and enthusiasm afford sports fans everywhere the chance to really get to know their heroes, talk to them directly, and discuss their views in a national forum. ® Tune in to SPORTS BYLINE USA LISTENfor IN! the ELECTRONIC ARTS SPORTS TRIVIA CONTEST for a chance to win a free EA SPORTS game. Check local radio listings. 10:00 p.m. to 1:00 a.m. E.T. 9:00 p.m. to 12:00 a.m. C.T. 8:00 p.m. to 11:00 p.m. M.T. 7:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. P.T. OFFICIAL 722805 SEAL OF FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • HOCKEY • HOCKEY • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY • FOOTBALL • BASKETBALL • GOLF BASEBALL • HOCKEY FOOTBALL QUALITY • BASKETBALL • FOOTBALL • HOCKEY • GOLF • BASEBALL • BASKETBALL ABOUT THE MAN: Mark Lesser NHL HOCKEY ‘94 SEGA EPILEPSY WARNING PLEASE READ BEFORE USING YOUR SEGA VIDEO GAME SYSTEM OR ALLOWING YOUR CHILDREN TO USE THE SYSTEM A very small percentage of people have a condition that causes them to experience an epileptic seizure or altered consciousness when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights, including those that appear on a television screen and while playing games. -

Anishinabek Education Operational by 2008 SAULT STE

Volume 18 Issue 8 Published monthly by the Union of Ontario Indians - Anishinabek Nation Single Copy: $2.00 October 2006 Anishinabek education operational by 2008 SAULT STE. MARIE – Anishinabek Nation mem- the nation-building process. “We are not building ber communities from across Ontario are in the fi nal from scratch, we are building on the foundation of stages of establishing an education system which the knowledge of our Elders, our language and our they have helped design and which is expected to traditions. In our schools, Anishinaabemowin will begin operating under their jurisdiction in Septem- be the primary language and English will be the sec- ber, 2008. ondary language,” the Grand Council Chief said. Political leaders and educators from across First Nations jurisdiction over educa- Anishinabek Territory participated in an Oct. 3- tion and the establishment of the Anishi- 5 symposium called “Anishinaabe Kino- nabek Education System have been under maadswin Nongo – Anishinaabe negotiation with Canada for over a decade, Pow-wow circuit ending Pane,” which translates to “An- and a vote on a fi nal agreement by the With the falling of the leaves, the 2006 Great Lakes pow-wow circuit is ishinaabe Education Today 42 Anishinabek member communi- winding down to its autumn conclusion. These men’s traditional dancers were in fi ne form at the 51st annual Curve Lake First Nation Pow-Wow – Forever Anishinaabe.” ties is expected to take place as early held Sept. 16-17 at Lance Woods Park. – Photo by Crystal Cummings In endorsing the Anishi- as September 2007. The Anishinabek nabek model, keynote speak- Education System is expected to be er Dr. -

Sport-Scan Daily Brief

SPORT-SCAN DAILY BRIEF NHL 03/23/19 Anaheim Ducks Colorado Avalanche 1137021 Ducks’ recent surge continues in 4-3 OT win over Sharks 1137053 Avalanche hosts the Chicago Blackhawks in referee Brad 1137022 Jakob Silfverberg, Ducks work overtime to defeat Sharks Watson’s swan song 1137023 Ducks and Ryan Kesler set to discuss his hockey future 1137054 What you need to know about the Blackhawks-Avalanche 1137024 Poor injury reports mean Kesler, Eaves should consider weekend series retiring as Ducks 1137055 Grubauer, defense help Avalanche beat Stars 3-1 1137056 Avalanche await word on Mikko Rantanen’s health Arizona Coyotes 1137025 In trying to promote rivalries, NHL's playoff structure is Columbus Blue Jackets neglecting its top teams 1137057 Frustrations fester after loss to Oilers 1137026 Return of short-handed goal specialist Michael Grabner 1137058 Pierre-Luc Dubois working on his face-offs helps Arizona Coyotes' playoff chase 1137059 Oilers 4, Blue Jackets 1 | Five takeaways 1137027 NHL Western Conference Wild Card tracker: Coyotes making playoff push Dallas Stars 1137028 Coyotes PK guru Scott Allen has more than earned his 1137060 Stars 2019 playoff tracker: Where Dallas sits in the stripes Western Conference standings (updated daily) 1137061 Despite being a healthy scratch for the majority of recent Boston Bruins games, Jamie Oleksiak's chance could come in an ins 1137029 Can Sean Kuraly climb higher in the Bruins lineup? 1137030 Bruins’ Brad Marchand is on a roll Detroit Red Wings 1137031 Boston Bruins assign winger Paul Carey to Providence 1137062 Red Wings' Taro Hirose earns high praise from Thomas 1137032 What we learned in Bruins' 5-1 win over Devils: Bruins' top Vanek. -

2019 NHL DRAFT Pre-Draft Notes

2019 NHL DRAFT Pre-Draft Notes 2019 NHL DRAFT COULD HAVE STRONG DOSE OF AMERICAN TALENT With many American players among the top-ranked prospects, a look at some of the country’s most successful showings in the NHL Draft: * Seven American-born players have been selected first overall in the NHL Draft, with Auston Matthews the last in 2016 by the Toronto Maple Leafs. * Five American-born players have been selected first overall by an American-based team: center Brian Lawton in 1983 (Minnesota North Stars), center Mike Modano in 1988 (Minnesota North Stars), goaltender Rick DiPietro in 2000 (New York Islanders), defenseman Erik Johnson in 2006 (St. Louis Blues) and forward Patrick Kane in 2007 (Chicago Blackhawks). * Since the seven-round draft was introduced in 2005, the most American-born players selected in one year is 66 (2014). * Including every NHL draft, the most American-born players selected in one year came in 1987 when 100 were chosen over 12 rounds. * The most American-born players selected in the first round of any draft is 12, set at the 2016 NHL Draft in Buffalo when Matthews topped the list at first overall. In addition to 2016, three other drafts have seen at least 10 American-born players selected in the first round: 11 in 2007, 10 in 2006 and 10 in 2010. * At least three American-born players have been selected among the top 10 on six occasions, including two years with four. MOST AMERICAN-BORN PLAYERS SELECTED IN TOP 10, ONE DRAFT YEAR Top 10 Picks Draft Year 4 2006 E. -

Autumn 2013 Volume 27

YOUR GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS 25 FREE th Anniversary Year BC BOOKWORLD “There’s this sign in a band office I saw once, and now it’s my mantra: First Nations People Have Always Worked for a Living.” GINO ODJICK, co-owner of Musqueam Golf & Learning Academy NEVERA new anthology IDLE profiles 16 aboriginal Canadians forging successful careers. See page 9 #40010086 PHOTO AGREEMENT MAIL SAWCHUCK LAURA PUBLICATION KINDLEFREE RATZINGER: GOD’S ROTTWEILER P.23 SECRET SOLDIERS MUTINY P.27 SURVIVING RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS P.11 VOL. 27 • NO. 3 AUTUMN 2013 TEACHER’S RELUCTANT PETP.29 SHELLEY HRDLITSCHKA 2 BC BOOKWORLD AUTUMN 2013 BCTOP* SELLERS PEOPLE Whitewater Cooks with Friends (Sandhill Book Marketing $34.95) by Shelley Adams The Garden That You Are (Sono Nis $28.95) by Katherine Gordon Little You (Orca $9.95) by Richard Van Camp and Julie Flett Ian T. Parsons No Easy Ride: Reflections on My Life in the RCMP (Heritage House $19.95) by Ian T. Parsons How Happy Became Homo- sexual & Other Mysterious Semantic Shifts (Ronsdale Press $19.95) by Howard Richler Vancouver United after their first win in Turin, en route to a world title. Where Happiness Dwells: A History of the Dane-zaa First Nations (UBC Press $34.95) by Robin Riddington & Jullian Riddington, with elders of the Dane-zaa First Nations Canada unlikely champs in Italy The Angelic Occurrence (Red Tuque Books $21.95) Vancouver United won its qualifying contests 2-1, 3-0, 2-0, 2-0; fol- N OVER-50S TEAM SPONSORED BY BC BOOKWORLD by Henry K.