Birds Observed Between Point Barrow and Herschel Island on the Artic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wwi 1914 - 1918

ABSTRACT This booklet will introduce you to the key events before and during the First World War. Taking place from 1914 – 1918, millions of people across the world lost their lives in what was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’. Fighting on this scale had never been seen before. The work in this booklet will help you understand why such a horrific conflict begun. Ms Marsh WWI 1914 - 1918 Year 8 History Why did the First World War begin? L.O: I can explain the causes of the First World War. 1. In what year did the war begin? 2. In what year did the war end? 3. How many years did it last? (Do now answers at end of booklet) The First World War begun in August 1914. It took the world by surprise, and seemed to happen overnight. In reality, tension between countries in Europe had been increasing for some years before. The final event that triggered war, the assassination of a young heir to the Austria – Hungary throne, demonstrates how this tension had been building. Europe in the early 20th century was a place where newly formed countries such as Italy started to challenge the dominance of countries with empires. An empire is when one country rules over others around the world. Some countries began to demand their independence and did not want to be ruled by an empire. The map opposite shows just how vast the empires of Europe were; Britain had control of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, East and South Africa and India. -

9594 the LONDON GAZETTE, 28 SEPTEMBER, 1915. Ibe Liable for the Assets of .The Said Deceased, Or Any, Colonel EDWARD THOMAS BROWELL, Deceased

9594 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 28 SEPTEMBER, 1915. ibe liable for the assets of .the said deceased, or any, Colonel EDWARD THOMAS BROWELL, Deceased. part thereof, so distributed, to any person or persons Pursuant to 22 and 23 Vic., cap. 35. of whose claims they 'shall not then have notice,— "IVfOTIGE is hereby given, that all persons having Dated this 24th day of September, 1915. _i_M claims against the estate of Colonel Edward GILL, ARCHER, MAPLES and DUN, 14, Cook- Thomas Browell, late of Merrow House, Merrow, street, Liverpool, Solicitors to the said Adminis-. •Surrey (who died on the llth 'day of August, 1915, and. 057 trator. •whose will, with a codicil thereto, was proved in the Principal Probate Registry, on the 23rd day of September, 1915, by the Reverend Frederick James BOBEET ELLIS, Deceased. Browe'fl, of Feltham Vicarage, Middlesex, and William Jebb Wigston, of 21, College-hill, London, E.G., two Pursuant-to the Act of Parliament 22 and 23 Viet., of the executors therein named], are hereby required c. 35. to send the particulars thereof, m writing. So the IVTOTIGE is hereby .given, that all persons having undersigned, Solicitors for the executors, on or before _Ll any debts, claims or demands upon or against the llth day of November, 1915, after which date the the estate of Robert Ellis, late of No. 52, Lough- said executors will proceed to distribute the assets, 'borough-road, West Bridigford, in the county of Not- of the deceased, having regard only to the claims of tingham, deceased (who died on the 28th day of July, which the executors shall then have had notice.— 1913, and whose will was proved by the executors, Dated the 24th September, 1915. -

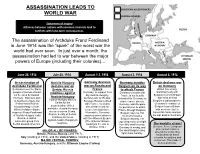

Timeline of Start Of

ASSASSINATION LEADS TO EUROPEAN ALLIED POWERS WORLD WAR CENTRAL POWERS Statement of Inquiry Alliances between nations with common interests lead to conflicts with long-term consequences. RUSSIA GERMANY GERMANY The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand FRANCE AUSTRIA- in June 1914 was the “spark” of the worst war the HUNGARY world had ever seen. In just over a month, the Bosnia assassination had led to war between the major OTTOMAN EMPIRE powers of Europe (including their colonies)… June 28, 1914 July 28, 1914 August 1-3, 1914 August 3, 1914 August 4, 1914 Assassination of Austria-Hungary Germany declares Germany invades Britain declares war Archduke Ferdinand declares war on war on Russia and Belgium on its way on Germany Serbia believes the Slavic Serbia; Russia France to attack France Britain has a long- people of Europe should mobilizes against Germany, to support their Germany’s border with standing treaty with Belgium in which Britain not be ruled by Austria- Austria-Hungary ally Austria-Hungary, France is too heavily Hungary. Bosnia is part declares war on Russia. defended for Germany to agreed to defend Austria-Hungary blames of Austria-Hungary, but Because Russia is allied attack France directly. Belgium’s independence. Serbia for the Serbia thinks Bosnia with France, Germany Germany asks Belgium Germany’s invasion of assassination of their should belong to them. also declares war on for permission to attack Belgium leaves Britain archduke. Austria-Hungary When Archduke (future France two days later. France through Belgium. with no choice but to declares war on Serbia. emperor) Franz-Ferdinand Meanwhile, Germany Belgium says no, but honor this treaty and join Russia, an ally of Serbia, of Austria-Hungary visits makes a secret alliance Germany invades the war against Germany. -

Felipe Angeles| Military Intellectual of the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1915

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 Felipe Angeles| Military intellectual of the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1915 Ronald E. Craig The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Craig, Ronald E., "Felipe Angeles| Military intellectual of the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1915" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2333. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2333 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR, MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE198ft FELIPE ANGELES: MILITARY INTELLECTUAL OF THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION 1913-1915 by Ronald E. Craig B.A., University of Montana, 1985 Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1988 Chairman^ Bagprd—of—Examiners Dean, Graduate School / & t / Date UMI Number: EP36373 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

French Press, Public Opinion and the Murder of Franz Ferdinand In

French press, public opinion and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand (28 June-3 August 1914) How French society entered the Great war? Unlocking sources • The aim of this communication is quite simple: how new ways of getting access to digital contents (through technical process such as OCR and NER) give us the opportunity to understand how French society entered the First World War in August 1914? • Regarding this topic, I have studied both private archives and French press issues made available through the project Europeana 14-18 (chronologically from the 29 of June, the day after the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand , heir of the austro-hungarian monarchy in Sarajevo to the 3rd of August, the day of the declaration of war of Germany on France) • I have used two different technologies I will come back later on: the optical recognition of characters and the named entities recognition, a process we have developped thanks to another European project, Europeana Newspapers Unlocking sources • One of the main concern for me was also to assess the impact of the use of these automated processes applied to historical sources • This question is quite important as I strongly believe that the use of such technical process modify deeply our access and our understanding of historical sources (in other words how automated process lead to a new way of writing history) Starting point Emile Spring 1914 Starting point Letter sent to his family in law 31st of July 1914 French historiography • J-J Becker, How French entered the war, 1977) • If we consider the succession of events from the assassination of the archduke Franz-Ferdinand the 28th of June in Sarajevo to the declaration of war on France the 3rd of August, the point of view promoted by J.J. -

When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

WHEN DIPLOMATS FAIL: AOSTRIAN AND ROSSIAN REPORTING FROM BELGRADE, 1914 Barbara Jelavich The mountain of books written on the origins of the First World War have produced no agreement on the basic causes of this European tragedy. Their division of opinion reflects the situation that existed in June and July 1914, when the principal statesmen involved judged the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, and its consequences from radically different perspectives. Their basic misunderstanding of the interests and viewpoints 'of the opposing sides contributed strongly to the initiation of hostilities. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the importance of diplomatic reporting, particularly in the century before 1914 when ambassadors were men of influence and when their dispatches were read by those who made the final decisions in foreign policy. European diplomats often held strong opinions and were sometimes influenced by passions and. prejudices, but nevertheless throughout the century their activities contributed to assuring that this period would, with obvious exceptions, be an era of peace in continental affairs. In major crises the crucial decisions are always made by a very limited number of people no matter what the political system. Usually a head of state -- whether king, emperor, dictator, or president, together with those whom he chooses to consult, or a strong political leader with his advisers- -decides on the course of action. Obviously, in times of international tension these men need accurate information not only from their military staffs on the state of their and their opponent's armed forces and the strategic position of the country, but also expert reporting from their representatives abroad on the exact issues at stake and the attitudes of the other governments, including their immediate concerns and their historical background. -

From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic

Open Archaeology 2016; 2: 209–231 Original Study Open Access Peter Dawson*, Richard Levy From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic DOI 10.1515/opar-2016-0016 Received January 20, 2016; accepted October 29, 2016 Abstract: Many of Canada’s non-Indigenous polar heritage sites exist as memorials to the Heroic Age of arctic and Antarctic Exploration which is associated with such events as the First International Polar Year, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the race to the Poles. However, these and other key messages of significance are often challenging to communicate because the remote locations of such sites severely limit opportunities for visitor experience. This lack of awareness can make it difficult to rally support for costly heritage preservation projects in arctic and Antarctic regions. Given that many polar heritage sites are being severely impacted by human activity and a variety of climate change processes, this raises concerns. In this paper, we discuss how virtual heritage exhibits can provide a solution to this problem. Specifically, we discuss a recent project completed for the Virtual Museum of Canada at Fort Conger, a polar heritage site located in Quttinirpaaq National Park on northeastern Ellesmere Island (http://fortconger.org). Keywords: Arctic; Heritage, Fort Conger, Virtual Reality, Computer Modeling, Education, Climate Change, Polar Exploration, Digital Archaeology. 1 Introduction Climate change and the emerging geopolitical significance of the Arctic have important implications for Canada’s polar heritage. In many Arctic regions, thawing permafrost, land subsidence, erosion, and flooding are causing irreparable damage to heritage sites associated with Inuit culture, historic Euro-North American exploration, whaling and the fur trade (Blankholm, 2009; BViikari, 2009; Camill, 2005; Hald, 2009; Hinzman et al., 2005; Morten, 2009; Stendel et al., 2008). -

Recent Climate-Related Terrestrial Biodiversity Research in Canada's Arctic National Parks: Review, Summary, and Management Implications D.S

This article was downloaded by: [University of Canberra] On: 31 January 2013, At: 17:43 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biodiversity Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tbid20 Recent climate-related terrestrial biodiversity research in Canada's Arctic national parks: review, summary, and management implications D.S. McLennan a , T. Bell b , D. Berteaux c , W. Chen d , L. Copland e , R. Fraser d , D. Gallant c , G. Gauthier f , D. Hik g , C.J. Krebs h , I.H. Myers-Smith i , I. Olthof d , D. Reid j , W. Sladen k , C. Tarnocai l , W.F. Vincent f & Y. Zhang d a Parks Canada Agency, 25 Eddy Street, Hull, QC, K1A 0M5, Canada b Department of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NF, A1C 5S7, Canada c Chaire de recherche du Canada en conservation des écosystèmes nordiques and Centre d’études nordiques, Université du Québec à Rimouski, 300 Allée des Ursulines, Rimouski, QC, G5L 3A1, Canada d Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, Natural Resources Canada, 588 Booth St., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0Y7, Canada e Department of Geography, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada f Département de biologie and Centre d’études nordiques, Université Laval, G1V 0A6, Quebec, QC, Canada g Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E9, Canada h Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada i Département de biologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, J1K 2R1, Canada j Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, Whitehorse, YT, Y1A 5T2, Canada k Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth St., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0E8, Canada l Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0C6, Canada Version of record first published: 07 Nov 2012. -

Northwest Passage Trail

Nunavut Parks & Special Places – Editorial Series January, 2008 NorThwesT Passage Trail The small Nunavut community of Gjoa Haven Back in the late eighteenth and nineteenth is located on King William Island, right on the centuries, a huge effort was put forth by historic Northwest Passage and home to the Europeans to locate a passage across northern Northwest Passage Trail which meanders within North America to connect the European nations the community, all within easy walking distance with the riches of the Orient. From the east, many from the hotel. A series of signs, a printed guide, ships entered Hudson Bay and Lancaster Sound, and a display of artifacts in the hamlet office mapping the routes and seeking a way through interpret the local Inuit culture, exploration of the ice-choked waters and narrow channels to the the Northwest Passage, and the story of the Gjoa Pacific Ocean and straight sailing to the oriental and Roald Amundsen. It is quite an experience lands and profitable trading. The only other to walk the shores of history here, learning of routes were perilous – rounding Cape Horn at the exploration of the North, and the lives of the the southern tip of South America or the Cape of people who helped the explorers. Good Hope at the southern end of Africa. As a result, many expeditions were launched to seek a passage through the arctic archipelago. Aussi disponible en français xgw8Ns7uJ5 wk5tg5 Pilaaktut Inuinaqtut ᑲᔾᔮᓇᖅᑐᖅ k a t j a q n a a q listen to the land aliannaktuk en osmose avec la terre Through the efforts of the Royal Navy, and WANDER THROUGH HISTORY Lady Jane Franklin, John Franklin’s wife, At the Northwest Passage Trail in the at least 29 expeditions were launched to community of Gjoa Haven, visitors can, seek Franklin and his men, or evidence of through illustrations and text on interpretive their fate. -

Geneva Convention Government Notice No. 937 of 1915

STATums OF THE REPuBLrc OF SOUTH AFiucA — INTERNATIONAL LAW GENEVA CONVENTION GOVERNMENT NOTICE NO. 937 OF 1915 Geneva Convention 3rd September, 1915 Prohibition under the Geneva Convention Act, 1911, of the Unauthorized use of the Red Cross Emblem HIs ExCELLENCY THE GovERNOR-GENERAL-IN-CouNcIL has been pleased, under article three of the Geneva Convention Act, 1911 (Union of South Africa), Order-in-Council, 1913 (the said Order being set forth in the First Schedule thereto), to declare the 1st day of October, 1913, to be the date on and after which the said Order-in-Council was of force and effect. It is further notified that the Geneva Convention Act, 1911 (as set forth in the Second Schedule hereto), has been of force and effect within the Union since the date of the passing of that Act, namely, the 18th day of August, 1911. Consequently the period of four years mentioned in sub-section (3) of section one of that Act, wherein the “Red Cross” or “Geneva Cross” emblem could, under the circum stances set forth in that sub-section, continue to be used as a trade mark, has lapsed from and after the 18th day of August, 1915. From the date last mentioned, therefore, it is an offence, in terms of sub-section (1) of section one of the Act as adapted by the said Order to use the said emblem of the “Red Cross” or “Geneva Cross” for the purpose of trade or business or for any other purpose whatsoever without the authority of His Excellency the Governor-General-in-Council. -

Strafford, Missouri Bank Books (C0056A)

Strafford, Missouri Bank Books (C0056A) Collection Number: C0056A Collection Title: Strafford, Missouri Bank Books Dates: 1910-1938 Creator: Strafford, Missouri Bank Abstract: Records of the bank include balance books, collection register, daily statement registers, day books, deposit certificate register, discount registers, distribution of expense accounts register, draft registers, inventory book, ledgers, notes due books, record book containing minutes of the stockholders meetings, statement books, and stock certificate register. Collection Size: 26 rolls of microfilm (114 volumes only on microfilm) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: The donor has given and assigned to the University all rights of copyright, which the donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the University from others. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] Strafford, Missouri Bank Books (C0056A); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-Columbia]. Donor Information: The records were donated to the University of Missouri by Charles E. Ginn in May 1944 (Accession No. CA0129). Processed by: Processed by The State Historical Society of Missouri-Columbia staff, date unknown. Finding aid revised by John C. Konzal, April 22, 2020. (C0056A) Strafford, Missouri Bank Books Page 2 Historical Note: The southern Missouri bank was established in 1910 and closed in 1938. -

How Did the First World War Start?

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country.