Pentecostalisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Prayer-Tongues” in Corinth?

8. WHAT ABOUT THE “PRAYER-TONGUES” IN CORINTH? THE CASE FOR SPEAKING IN UNKNOWN TONGUES www.thebiblejesus.com aving looked at the three historic occasions in the Book of Acts when “tongues” were H used to advance the Gospel of Christ in the world, we now come to exceedingly muddy waters! We are going to ask the question: What About the “Prayer-Tongues” in Corinth? Those who believe the “tongues” in First Corinthians chapters 12 - 14 are “ecstatic utterances” with no recognisable language components of grammar and syntax, must explain that these “prayer tongues” are essentially a very different kind of language to what we have in Acts chapters 2, 10 and 19. Recall that the Spirit-inspired “tongues” in Acts were languages always understood by an audience. Interpretation of the languages in Acts is not indicated as ever needed, for they were languages understood and addressed to men in the context of preaching the Gospel. It was always Tongues and Prophecy --- languages for preaching the Good News. Can it be demonstrated then, that when we come to the “gift of tongues” at Corinth we meet a different genre altogether --- that of “unknown tongues” (as per KJV) ? If the modern practice of “speaking in unknown tongues” is to be justified, the case must be made that the various kinds of tongues (12: 10) are valid “heavenly tongues”. MY METHOD Before we get in earnest, I need to lay out how I am going to approach this hot-potato subject. It would literally take me an entire book to adequately deal with every aspect of the matter. -

Speaking in Tongues

SPEAKING IN TONGUES “He who speaks in a tongue edifies himself” 1 Corinthians 14:4a Grace Christian Center 200 Olympic Place Pastor Kevin Hunter Port Ludlow, WA 8365 360 821 9680 mailing | 290 Olympus Boulevard Pastor Sherri Barden Port Ludlow, WA 98365 360 821 9684 Pastor Karl Barden www.GraceChristianCenter.us 360 821 9667 Our Special Thanks for the Contributions of Living Faith Fellowship Pastor Duane J. Fister Pastor Karl A. Barden Pastor Kevin O. Hunter For further information and study, one of the best resources for answering questions and dealing with controversies about the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the gift of speaking in tongues is You Shall Receive Power by Dr. Graham Truscott. This book is available for purchase in Shiloh Bookstore or for check-out in our library. © 1996 Living Faith Publications. All rights reserved. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Unless otherwise identified, scripture quotations are from The New King James Version of the Bible, © 1982, Thomas Nelson Inc., Publishers. IS SPEAKING IN TONGUES A MODERN PHENOMENON? No, though in the early 1900s there indeed began a spiritual movement of speaking in tongues that is now global in proportion. Speaking in tongues is definitely a gift for today. However, until the twentieth century, speaking in tongues was a commonly occurring but relatively unpublicized inclusion of New Testament Christianity. Many great Christians including Justin Martyr, Iranaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Augustine, Chrysostom, Luther, Wesley, Finney, Moody, etc., either experienced the gift themselves or attested to it. Prior to 1800, speaking in tongues had been witnessed among the Huguenots, the Camisards, the Quakers, the Shakers, and early Methodists. -

When We Speak in Tongues, We Are Making a Conscious Decision by Faith to Speak As the Holy Spirit Is Giving Us the Language Or the Words to Say

Purpose of Tongues Part 2 Review: - When we speak in tongues, we are making a conscious decision by faith to speak as the Holy Spirit is giving us the language or the words to say. - We can speak in two kinds of tongues: A tongue that is known in the earth and an unknown tongue that no man knows. - Tongues are used to convey a message to the church in the public setting and work in conjunction with the gift of interpretation. - The gift of tongues to convey a message to the church found 1 Corinthians 12 is not the same as the tongues you receive through the baptism in the Holy Ghost. o The gift of tongues mentioned in 1 Corinthians chapter 12 is a gift for ministering to the body of Christ in the public church service and must be accompanied with the gift of interpretation. o Not everyone will have this gift. o But the gift of tongues you receive through the baptism of the Holy Spirit is for everyone and for your personal edification. So, let’s talk about the tongue for personal edification. This tongue is the unknown tongue mentioned in 1 Corinthians 14:2 and 1 Corinthians 14:4. This is the tongue you receive when you are baptized in the Holy Spirit. Look what Paul says about this tongue in 1 Corinthians 14:4 - So, there’s a tongue that we can speak in that’s not a known tongue and it is for our personal edification o Once again this is a different tongue then the one referred to in 1 Corinthians 12. -

A BIBLICAL STUDY of TONGUES

A BIBLICAL STUDY of TONGUES by the late Dr. John G. Mitchell reformatted and edited by: Mr. Gary S. Dykes [several comments were added by Mr. Dykes, in brackets] 1 Is speaking in tongues the evidence of a Spirit-filled, Spirit controlled life, the outward manifestation of the baptism ‘of the Spirit of God? This is one of the important questions at issue in the Christian world today. There is much preaching and writing concerning it, much discussion and questioning and inquiry. We hear of groups meeting in our universities and colleges, and in churches of every denomination, seeking this experience. In some of our religious magazines we find accounts of the experiences of those who claim a special anointing from God, evidenced by speaking tongues. I am sure this points out the fact that among God’s people there are many hungry hearts with a great desire to know God and a real longing to see the power of God manifested. However, one thing I have noticed as I have heard and read these testimonies is that the emphasis has always been an the experience and there is very little said about the teaching of the Scripture concerning it. There is a seeking of an experience rather than a searching of the Word of God. I believe the reason why there is misunderstanding and confusion is because there is not a clear understanding of all that the Word declares. Whatever we seek let us be sure that it is according to the Word of God. This cannot be emphasized too much. -

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues As Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives

An Evaluation of Speaking in Tongues as Angelic Language from the Judaean and Early Christian Perspectives Eben de Jager Abstract In contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic circles glossolalia is Keywords often referred to as the tongues of angels, with 1 Corinthians 13:1 Tongues of angels, angeloglossy, xenolalia, glossolalia, being quoted. Yet writings on the tongues of angels available in hebraeophone. the first century and the Judaean context from which Paul wrote do not support such a narrative. In addition, the Corinthian About the Author1 context and the writings of the Church Fathers also paint a picture Eben de Jager not aligned with the contemporary view. An analysis of 1 Masters Degree, UNISA. He is a member of Spirasa (The Spirituality Corinthians 13:1–3 shows it to be a weak support for establishing Association of South Africa). the concept of contemporary ‘angelic language’. Other influences may have given rise to the idea of glossolalia as the tongues of angels, but the Bible does not appear to support such a view. 1 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the beliefs of the South African Theological Seminary. Conspectus—The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary ISSN 1996-8167 https://www.sats.edu.za/conspectus/ This article: https://www.sats.edu.za/de-jager-an-evaluation-of-speaking-in-tongues Conspectus, Volume 28, September 2019 35 1. Introduction There are many different views on the gift of tongues, or glossolalia, in Christian circles today. Cartledge (2000:136–138) lists twelve possibilities of what the linguistic nature of glossolalia might be, based on his study of various scholars’ work. -

You Need to Know About Speaking in Tongues”

“All You Need to Know About Speaking in Tongues” Robert M. Thompson, Pastor Corinth Reformed Church 150 Sixteenth Avenue NW Hickory, North Carolina 28601 828.328.6196 corinthtoday.org (© 2019 by Robert M. Thompson. Unless otherwise indicated, Scriptures quoted are from The Holy Bible, New International Version, Copyright 2011 by New York International Bible Society.) Use any gift God gives you in love to build others up. 1 Corinthians 14:1-25 August 25, 2019 (Corinth sermons are available in audio and print forms at corinthtoday.org/sermons.) What it is My sermon title today is rather bold. I honestly don’t believe I can articulate all you need to know in one sermon about this or anything else. However, besides the stories in the book of Acts, 1 Corinthians is the only place in the New Testament that treats the matter of speaking in tongues in any details. Before I continue, I’d like to conduct a brief poll. I’ll give you a scale of 1-5. 1: I have studied or experienced much about speaking in tongues and have well-informed opinions on the matter. 5: I have no clue what you’re talking about. For those of you on the 1-2 end of the scale, regardless of what your well- informed opinion is, I ask only for your humility and patience. For those of you on the 4-5 end of that scale, here’s a short definition: speaking in tongues is the ability to speak in a language you never studied. (The technical term is “glossolalia.”) In other words, by the power of the Holy Spirit, your mouth forms words and syllables either directly to God in prayer or to others on God’s behalf. -

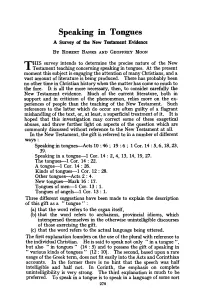

Speaking in Tongues a Survey of the New Testament Evidence

Speaking in Tongues A Survey of the New Testament Evidence BY RoBERT BANKS AND GEOFFREY MooN HIS survey intends to determine the precise nature of the New T Testament teaching concerning speaking in tongues. At the present moment this subject is engaging the attention of many Christians, and a vast amount of literature is being produced. There has probably been no other time in Christian history when the matter has come so much to the fore. It is all the more necessary, then, to consider carefully the New Testament evidence. Much of the current literature, both in support and in criticism of the phenomenon, relies more on the ex periences of people than the teaching of the New Testament. Such references to the latter which do occur are often guilty of a flagrant mishandling of the text, or, at least, a superficial treatment of it. It is hoped that this investigation may correct some of these exegetical abuses, and throw further light on aspects of the question which are commonly discussed without reference to the New Testament at all. In the New Testament, the gift is referred to in a number of different ways: Speaking in tongues-Acts 10 : 46 ; 19 : 6 ; 1 Cor. 14 : 5, 6, 18, 23, 39. Speaking in a tongue-1 Cor. 14 : 2, 4, 13, 14, 19, 27. The tongues-1 Cor. 14 : 22. A tongue-1 Cor. 14 : 26. Kinds of tongues-1 Cor. 12: 28. Other tongues-Acts 2: 4. New tongues-Mark 16 : 17. Tongues of men-1 Cor. 13: 1. Tongues of angels-1 Cor. -

Guide: How to Speak in Tongues

Guide: How To Speak In Tongues Why? One of the ways we can really develop in listening prayer is, rather ironically, by speaking. Speaking in tongues is an amazing and unique way we can activate our prayer lives and in particular, our ability to hear God. While still viewed as a controversial gift amongst some in the church - particularly in reaction to the charismatic renewal of the last 50 years - the reality is that many generations of Christians have received this ‘gift of the Spirit’ from the birth of the church up until today. Speaking in tongues doesn’t make you a better Christian (or person, for that matter) but it is a gift that is for everyone. And it could make us more effective in praying and hearing God. This prayer tool will help you better understand and develop the Spirit’s gift of speaking in tongues. Scriptural Examples: Acts 2:4 “All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit enabled them.” 1 Corinthians 14:2 “For anyone who speaks in a tongue does not speak to people but to God. Indeed, no one understands them; they utter mysteries by the Spirit.” Inspiring Quotes: “We enter the heavenlies by means of a heavenly language that condescends to the use of our feeble, stammering tongues to express the inexpressible.” -- Richard Foster HOW? The first time we hear someone ‘speaking in tongues’, or we read about it, feels weird. But if we step back from our rational sensibilities for a moment and think about the fact that we are first and foremost Spirit beings with bodies – not as we are prone to think, the other way around – then maybe it’s not so far-fetched after all! Our spirit is where the real ‘us’ is anchored – we groan and ache in our spirits, we experience joy and love and connection in our spirits – and all of these emotions and connections release a response in us that doesn’t always sound like English. -

Speaking in Tongues in the Restoration Churches

AR TICLES AND ESSAYS Speaking in Tongues in the Restoration Churches Lee Copeland "WE BELIEVE IN THE GIFT OF TONGUES, prophecy, revelation, visions, heal- ing, interpretation of tongues, and so forth" (Seventh Article of Faith). While over five million people in the United States today speak in tongues (Noll 1983, 336), very few, if any, are Latter-day Saints. How- ever, during the mid-1800s, speaking in tongues was so commonplace in the LDS and RLDS churches that a person who had not spoken in tongues, or who had not heard others do so, was a rarity. Journals and life histories of that period are filled with instances of the exercise of this gift of the Spirit. In today's Church, the practice is almost totally unknown. This article summarizes the various views of tongues today, clarifies the origin of tongues within the restored Church, and details its rise and fall in the LDS and RLDS faiths. There are two general categories of speaking in tongues: glos- solalia, speaking in an unknown language, usually thought to be of heavenly, not human, origin; and xenoglossia, miraculously speaking in an ordinary human language unknown to the speaker. When no dis- tinction is made between these two types of speech, both types are collectively referred to as glossolalia. On the day of Pentecost, Christ's apostles were gathered together. "And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance. Now when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together, and were con- founded, because that every man heard them speak in his own language" (Acts 2:4, 6). -

Fiery Tongues and Mystical Motivations: Glossolalia in a Forensic Population Is Associated with Mania and Sexual/Religious Delusions

Anthony G. Hempel,1 D.O., M.A.; J. Reid Meloy,2 Ph.D., M.Div.; Robert Stern,3 D.O., M.A.; Shinichi John Ozone,1 Ph.D., M.A.; and B. Thomas Gray,1 Ph.D. Fiery Tongues and Mystical Motivations: Glossolalia in a Forensic Population is Associated with Mania and Sexual/Religious Delusions REFERENCE: Hempel AG, Meloy JR, Stern R, Ozone SJ, Gray the beginning of the New Testament description, that the basic def- BT. Fiery tongues and mystical motivations: glossolalia in a foren- inition of glossolalia was not clear. sic population is associated with mania and sexual/religious delu- sions. J Forensic Sci 2002;47(2):305–312. The early Christians argued over the meaning and/or relevance of glossolalia. The Apostle Paul viewed tongues as threatening to ABSTRACT: Comparisons are made between a nonrandom sam- the church, the speaker, and the influence of the Church on the out- ple of 18 glossolalists and 130 non-glossolalists admitted to a max- side world (3). Paul was concerned that individuals outside the imum-security forensic hospital. The glossolalic mentally disor- Church would believe that the Church fostered insanity (3). Patti- dered offender exhibited a predominance of diagnoses in the manic son and Casey (2) pointed out the debate that ensued over the first spectrum, and was typically psychotic. The delusions, hallucina- two centuries among various Christians regarding the meaning of tions, and crimes were predominately of a religious and sexual na- ture. Glossolalist perpetrators tended to be female. We review the glossolalia: the Spirit of God speaking through the person (God extant research on glossolalia in both normal and clinical samples, possession); the Devil speaking through the person (Demon pos- and integrate our findings, the first study of glossolalia in a forensic session); the person was given the supernatural ability to speak in setting. -

All About Speaking in Tongues Fernand Legrand “Le Signal” CH-1326 – Juriens Switzerland Phone: 024.453.14.47 Source

All About Speaking in Tongues Fernand Legrand “Le Signal” CH-1326 – Juriens Switzerland Phone: 024.453.14.47 Source: http://www.seefrance.net/tongues.html Contents PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1 – ANALYSIS OF THE CHARISMATIC RENEWAL .................................................... 5 CHAPTER 2 – A MESSAGE TO MEN? ............................................................................................. 9 Scriptural Pattern? ......................................................................................................................... 9 Prevented from Seeing ................................................................................................................. 10 Scriptural Verification ................................................................................................................. 12 Papering over the cracks .............................................................................................................. 14 CHAPTER 3 – A SIGN FOR BELIEVERS? ..................................................................................... 15 The Unbelievers’ Identity ............................................................................................................ 16 The Analogy of Faith .................................................................................................................... 18 Superiority Complex ................................................................................................................... -

Do You Know the Holy Spirit? ’S Gift of Lesson Seven: the Spirit Speaking in Tongues

Mark E. Larson Do You Know the Holy Spirit? ’s Gift of Lesson Seven: The Spirit Speaking in Tongues Introduction: The Many Beliefs People Have of Speaking in Tongues. A. Many believe all Christians can have this gift today. “ When the early believers were filled, they spoke in other tongues and the same holds true today. Millions of believers worldwide share the exact testimony: when they initially were baptized in the Holy Spirit they spoke in unknown tongues. This is the truth which Pentecostals ” consistently affirm. - The General Council of the Assemblies of God “ The Gift of Tongues (D&C 46:24): Sometimes it is necessary to communicate the gospel in a language we have not learned. When this happens, the Lord can bless us with the ability to speak … that language Many faithful members have been blessed with the gift of tongues. (See ” Joseph Fielding Smith, Answers to Gospel Questions, 2:32-33.). www.lds.org – The Assembly of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. “ Spiritual Mediumship: A medium is one whose organism is sensitive to vibrations from the Spirit World and through whose instrumentality, intelligences in that world are able to convey messages and produce the phenomena of Spiritualism. The phenomena of Spiritualism consists … of: prophecy, clairvoyance, clairaudience, gift of tongues and any other manifestation which ” – proves the continuity of life. The National Spiritualist Association of Assemblyes www.nsac.org/spiritualism “This marvelous personal encounter is known as "the baptism with the Holy Spirit," and it is accompanied by the miracle of "speaking in tongues." It wasn't for the disciples alone; you too ” can have this experience--your very own Pentecost.