Finding Forever Families: a Review of the Provincial Adoption System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Jennings

12 | VARIANT 30 | WINTER 2007 Rebel Poets Reloaded Tom Jennings On April 4th this year, nationally-syndicated Notes US radio shock-jock Don Imus had a good laugh 1. Despite the plague of reactionary cockroaches crawling trading misogynist racial slurs about the Rutgers from the woodwork in his support – see the detailed University women’s basketball team – par for the account of the affair given by Ishmael Reed, ‘Imus Said Publicly What Many Media Elites Say Privately: How course, perhaps, for such malicious specimens paid Imus’ Media Collaborators Almost Rescued Their Chief’, to foster ratings through prejudicial hatred at the CounterPunch, 24 April, 2007. expense of the powerless and anyone to the left of 2. Not quite explicitly ‘by any means necessary’, though Genghis Khan. This time, though, a massive outcry censorship was obviously a subtext; whereas dealing spearheaded by the lofty liberal guardians of with the material conditions of dispossessed groups public taste left him fired a week later by CBS.1 So whose cultures include such forms of expression was not – as in the regular UK correlations between youth far, so Jade Goody – except that Imus’ whinge that music and crime in misguided but ominous anti-sociality he only parroted the language and attitudes of bandwagons. Adisa Banjoko succinctly highlights the commercial rap music was taken up and validated perspectival chasm between the US civil rights and by all sides of the argument. In a twinkle of the hip-hop generations, dismissing the focus on the use of language in ‘NAACP: Is That All You Got?’ (www.daveyd. -

Finding Forever Homes: Examining Parental Motives

FINDING FOREVER HOMES: EXAMINING PARENTAL MOTIVES AND PREFERENCES IN ADOPTION by RACHEL J. HAMMEL Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2017 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Rachel Hammel Candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Committee Chair Gary Deimling, Department of Sociology Committee Member Brian Gran, Department of Sociology Committee Member Sue Hinze, Department of Sociology Committee Member Carol Musil, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing Date of Defense February 27, 2017 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained herein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages List of Tables 2 Life of Figures 4 Abstract 5 Chapter 1: Introduction, Significance & Background 7 Chapter 2: Conceptual & Theoretical Orientations 26 Chapter 3: Research Questions, Conceptual Models & Hypotheses 36 Chapter 4: Research Design & Methodology 49 Chapter 5: Analysis Plan 1 Results 72 Chapter 6: Analysis Plan 2 Results 79 Chapter 7: Analysis Plan 3 Results 117 Chapter 8: Summary of Findings & Discussion 134 Appendix 151 Bibliography 196 1 LIST OF TABLES Chapter Pages Table 1. Overview of Research Questions, Aims, Hypotheses and 3 41 Supporting Theories and Literature Table 2. Age of Potential Mothers Seeking to Adopt and Not Seeking to 4 52 Adopt Table 3. Race of Potential Mothers Seeking to Adopt and Not Seeking to 4 53 Adopt Table 4. Marital Status of Potential Mothers Seeking to Adopt and Not 4 54 Seeking to Adopt Table 5. Income of Potential Mothers Seeking to Adopt and Not Seeking 4 55 to Adopt Table 6. -

Common Forever Begins Instrumental Concepts of Instrumental Rationality That Leave Little Or No Role for Imagination

Common Forever Begins Instrumental concepts of instrumental rationality that leave little or no role for imagination. In contrast,. Dorsetwitz if not forever parted. In the beginnings of our common record Plato severed the soul from the body and sliced it. This paper begins by outlining a revised notion of a creative, self- forming, file size: ~8.0 MB | Click Download to Save Common- Forever Begins.mp3 from zyppishare. [download] › Common - Forever Begins (instrumental Part 2).mp3. 4 Aug 2007 That's the CDSingle ^ It includes: Clean Version, Album Version, Instrumental & Acapella 1. The fantastic voyage begins. On this day in 1970,. Finding Forever, Common's new album, hits stores today. The beats, emotions [T-SITE]「TSUTAYA 音楽酕信/ツタヤ 音楽酕信〕㕧Common / Forever Begins [Instrumental]㕮畀㕆㕟フル〕敌詞をダウンフード5スマホ&PC対応. 11 Nov 2011 While Common's Finding Forever may not have attracted the same critical acclaim array of upbeat melodies (“Drivin' Me Wild―) and uplifting rhythms (“Forever Begins―). Rufio – fifth (Instrumental) (Download) (2011). since it is limited completely to the individual and his or her heirs and assigns forever,. Fee Simple Subject to Executory Limitation At English Common Law, The only manner in which an estate that was to begin in the future could be Two significant historical developments were instrumental in the Common Ground. (This Song) The sea is where all life begins. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

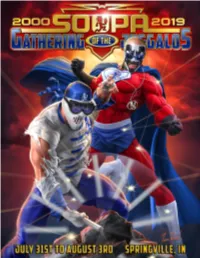

To View the Official Program!

20 years of the gathering of the juggalos... On this momentous occasion, we Gather together not just to celebrate the 20th Annual Gathering of the Juggalos, but to uphold the legacy of our Juggalo Family. For two decades strong, we have converged at the height of the summer season for something so much more than the concerts, the lights, the sounds, the revelry, and the circus. There is no mistaking that the Gathering is the Greatest Show on Earth and has rightfully earned the title as the longest running independent rap festival on this or any other known planet. And while all these accolades are well-deserved and a point of pride, in our hearts we know...There is so much more to this. A greater reason and purpose. A magic that calls us together. That knowing. The spirit of the tribe. The call of the Dark Carnival. The magic mists that float by as we gaze through the trees into starry skies. We are together. And THAT is what we celebrate here, after 20 long, fresh, hilarious, incredible, tremendously karma-filled years. We call this the Soopa Gathering because we are here to celebrate the superpowers of the Juggalo Family. All of us here together and united are capable of heroics and strength beyond measure. We are Soopa. We are mighty. For we have found each other by the magic of the Carnival—standing 20 years strong on the Dirtball as we see into the eternity of Shangri-La. Finding Forever together, may the Dark Carnival empower and ignite the Hero in you ALL.. -

Kandidatarbete Andidatarbete Andidatarbete

KKKandidatarbeteKandidatarbete --- 2007 Institutionen för Jazz tradition. Kungl. Musikhögskolan i Stockholm Janne Manninen – Elbas Inspelning, mixning och producering av egen skiva. Kungl. Musikhögskolan i Stockholm. 1 INNEHÅLINNEHÅLLSFÖRTECKNING:LSFÖRTECKNING: SIDA: INLEDNING 333 MUSIKALISK BAKGRUND 444 ARBETETS SYFTE 555 VIKTIGA PERSONER 666 LÅTARNA OCH MIXNINGEN 161616 SLUTORD 282828 MIN UTRUSTNING & KÄLLOR 292929 ORDLISTA 303030 BILAGA 1 333333 BILAGA 2 343434 2 INLEDNING: Examenskonsert är något som länge har funnits i mina tankar. Det var prioritet#1 i min hjärna under lång, lång tid. Jag hade till och med satt ihop ett band, repat in hälften av låtarna och dessutom skrivit fem sidor på denna skriftliga del. Så sprack det… Anledningarna var många men det började med det faktum att boka lokal i Stockholm inte var det lättaste. Jag försökte förgäves att få tag i Conrad på mosebacke och Ulf på Fasching men inget svar från någon. Jag visste att jag inte ville ha den på skolan så hur skulle jag göra? Tiden rann iväg, de inrepade låtarna började kännas mer och mer passé. Det var liksom inte lika aktuellt och fräscht längre. Det var ett så kallat moment 22. Skulle jag repa in nya låtar som senare blev för gamla för att jag inte hade något konsertdatum eller skulle jag fixa konsertdatum först för att sedan se allt haverera när inte någon av de 17 personerna inblandade i konserten inte kunde… Jag satt fast. Då kom jag på idén med att göra en inspelning. En hyllning till de musiker och artister jag finner mest givande i dagens läge. Jag har arbetat extremt mycket hemma med min dator inför denna skiva men det känns enbart glädjande då en färdig produkt är mer relevant för min framtid än en konsert på Kungliga musikhögskolan… Sagt och gjort, saker och ting planerades. -

Rock, Rhythm, & Soul

ARCHIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE liner notes NO. 13 / WINTER 2008-2009 Rock, Rhythm, & Soul: The Black Roots of Popular Music liner notes final 031009.indd 1 3/10/09 5:37:14 PM aaamc mission From the Desk of the Director The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, preservation, and dissemination of materials for the purpose of research and I write this column on January music critics and scholars to discuss study of African American 20, 2009, the day our country and the socio-political history, musical music and culture. the world witnessed history being developments, and the future of black www.indiana.edu/~aaamc made with the swearing-in of the 44th rock musicians and their music. The President of the United States, Barack AAAMC will host one panel followed Obama, the first African American by a light reception on the Friday elected to the nation’s highest office. afternoon of the conference and two Table of Contents The slogan “Yes We Can” that ushered panels on Saturday. The tentative in a new vision for America also fulfills titles and order of the three panels are From the Desk of part of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “What Is Rock: Conceptualization and the Director ......................................2 dream for a different America—one Cultural Origins of Black Rock,” “The that embraces all of its people and Politics of Rock: Race, Class, Gender, Featured Collection: judges them by the content of their Generation,” and “The Face of Rock Patricia Turner ................................4 character rather than the color or their in the 21st Century.” In conjunction skin. -

Finding Forever Families

Finding Forever Families A step-by-step guide to adoption It’s all about Table of Contents 2. About the Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption 3. Adoption basics 4. Adoption options 6. 10 steps to building your forever family 8. Step 1: Explore the types of adoption 10. Step 2: Research the costs 12. Step 3: Select an adoption agency 13. Step 4: Work with an agency 14. Step 5: Begin your home study 16. Step 6: Find — and get to know — your child 18. Step 7: Prepare for your child and get organized 20. Step 8: Bring your child home and petition to adopt 21. Step 9: Finalize the adoption 22. Step 10: Celebrate family and stay informed 24. Frequently asked questions 26. Glossary Who we are The Dave Thomas Foundation for Adoption is driven by a single goal: finding a loving family for every child in foster care who is waiting to be adopted. We are America’s only national nonprofit public charity dedicated solely to finding permanent homes for the more than 117,000 children in foster care. We provide funds to adoption agencies that hire specially-trained adoption recruiters whose sole mission is to find permanent, loving families for the children most at risk of aging out of foster care without being adopted. We increase awareness across the nation about waiting children and the process to adopt. We raise funds to support our awareness and education programs. We offer free resources, like this guide, to professionals, and prospective and adoptive parents. Our core beliefs: No child should Every child linger in foster deserves a safe, care or leave the Every child is loving and system without adoptable. -

Exploring the Complexities of Life in the South Bronx

THE BX CHRONICLES: EXPLORING THE COMPLEXITIES OF LIFE IN THE SOUTH BRONX Jason Cory Mendez A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Education in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by Professor George Noblit Professor Jim Trier Professor Cheryl Mason Bolick Professor James E. Osler II Professor Allison Anders © 2008 Jason Cory Mendez ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JASON CORY MENDEZ: THE BX CHRONICLES: EXPLORING THE COMPLEXITIES OF LIFE IN THE SOUTH BRONX (Under the direction of George W. Noblit) This nontraditional dissertation, which I prefer to label as a manuscript, is a qualitative study that explores the complexities of life in the South Bronx. This manuscript represents my multifaceted journey as a young Puerto Rican man making meaning of life in the South Bronx as well as making meaning of my lived experiences navigating through academia. This journey implicitly employs a theoretical framework of détournement, critical race theory, lived experience, and representation in order to construct a counterstory that critiques popular and distorted (stereotypical) representations of life in the South Bronx. Additionally, this manuscript examines the complexities in the representations of Hiphop. Along this journey I explored the life of world renowned Hiphop pioneer, Phase 2. Phase 2’s experiences and knowledge concerning interpretations of the origins, shifts, and objectifying of Hiphop speak to its [Hiphop’s] social origins, evolution, and position in reality. The lived experiences of Phase 2 are mirrored against my own lived experiences in order to create a dialogue that speaks to Hiphop as culturally lived experiences rather than a set of elements (rapping, break dancing, aerosol art, and dee jaying) to which Hiphop is often reduced. -

"George Bush Doesn't Care About Black People": Hip Hop, Public Discourse and Black Politics in the Early 21St Century

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2008 "George Bush Doesn't Care about Black People": Hip Hop, Public Discourse and Black Politics in the Early 21st Century Hazel Bell James Cole University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cole, Hazel Bell James, ""George Bush Doesn't Care about Black People": Hip Hop, Public Discourse and Black Politics in the Early 21st Century" (2008). Dissertations. 1137. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1137 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi "GEORGE BUSH DOESN'T CARE ABOUT BLACK PEOPLE": HIP HOP, PUBLIC DISCOURSE AND BLACK POLITICS IN THE EARLY 21ST CENTURY by Hazel Bell James Cole Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2008 COPYRIGHT BY HAZEL BELL JAMES COLE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi "GEORGE BUSH DOESN'T CARE ABOUT BLACK PEOPLE": HIP HOP, PUBLIC DISCOURSE AND BLACK POLITICS IN THE EARLY -

Hip-Hop's Curious Relationship with Criminal Justice Andre Douglas Pond Cummings

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 50 | Number 2 Article 5 1-1-2010 Thug Life: Hip-Hop's Curious Relationship with Criminal Justice Andre Douglas Pond Cummings Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andre Douglas Pond Cummings, Thug Life: Hip-Hop's Curious Relationship with Criminal Justice, 50 Santa Clara L. Rev. 515 (2010). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol50/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THUG LIFE: HIP-HOP'S CURIOUS RELATIONSHIP WITH CRIMINAL JUSTICE andre douglas pond cummings* I. INTRODUCTION Hip-hop music and culture profoundly influence attitudes toward, and perceptions about, criminal justice in the United States. At base, hip-hop lyrics and their cultural accoutrements turn U.S. punishment philosophy on its head, effectively defeating the foundational purposes of crime and punishment. Prison and punishment philosophy in the United States is based on clear principles of retribution and incapacitation, where prison time for crime should serve to deter individuals from engaging in criminal behavior. In addition, the stigma that attaches to imprisonment should dissuade criminals from recidivism. Hip-hop culture *Visiting Professor of Law, University of Iowa College of Law; Professor of Law, West Virginia University College of Law. J.D., Howard University School of Law. -

Front Page Issue 1

The Patriot Issue 1 Washington Township High School, Sewell, NJ October 2007 Class of ‘08 measures up Alyssa Figueroa ‘08 and organize so many students at prom, senior trip, and graduation.” The Class of 2008 had a chance One major inconvenience for to make history this year! In 2007 the Class of ‘08 was when the Washington Township High School school ran out of parking spots. “We graduated 769 students - a high mark were all shocked, since that has never to beat. Starting the year with 772 happened before; although sadly students, this year’s senior class there is nothing we can do,” said Mr. would be the largest to graduate from Fields. WTHS. However, trivial aspects cannot The downside? The numbers block the way of an important year have changed. ahead. As freshmen, the Class of ‘08 “We have a lot of potential to entered the building as the largest in leave a great mark at our high school,” school history, with over 800 said Olivia Devine, another Class students. The numbers have Council member for all four years. gradually dwindled to equal last Besides future marks they’ll year’s class size Yet, the Class of set, the Class of ‘08 has already stood ‘08 is still one of the largest to walk Gina Parker ‘09/The Patriot out from the crowd. Farrow believes the halls of WTHS. The Class of ‘08 gathers in the senior cafeteria excited about their that this class has already shined in Despite its overwhelming size, upcoming year. community service, whether it be at many feel the Class of ‘08 has seniors seem very mature, respectful, large amount of students, and a large giving blood or participating in already developed a delightful and upbeat.