Insuring Against a Drop in an Athlete's Draft Position

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RB Ka'deem Carey, Arizona

2014 NFL DRAFT SCOUTING REPORT MARCH 2, 2014 NFL Draft 2014 Scouting Report: RB Ka’Deem Carey, Arizona *Our RB grades can and will change as more information comes in from Pro Day workouts, leaked Wonderlic test results, etc. We will update ratings as new info becomes available. *We use the term “Power RB” to separate physically bigger, more between-the-tackles–capable RBs from our “speed RBs” group. “Speed RBs” are physically smaller, but much faster/quicker, and less likely to flourish between the tackles. Ka'Deem Carey is the Derek Carr of RBs prospects in 2014. That is to say, Carey is a system guy with puffed-up stats because his team runs the ball heavily. It's no different than being wowed by Carr's raw passer numbers this year, and not considering the context of throwing the ball twice as much as most college teams. Double the throws...double the output. The masses see the raw totals and go predictably nuts for it. One time this year, Carey had 48 carries in a game. Give me a break... It's one thing to be awesome and have a bunch of carries. It's another to be mediocre and have heavy carry numbers making you look better than you really are. When Carey had 48 carries (vs. Oregon), he had 4.3 yards per carry...not impressive. In fact, several games this year ended with Carey below 5.0 yards per carry for the contest. We'll get into the numbers in the next section. I watched the tape on Carey, and I have no idea (actually, I do) why scouts and football analysts went bonkers. -

04 Coaches-WEB.Pdf

59 Experience: 1st season at FSU/ Taggart jumped out to a hot start at Oregon, leading the Ducks to a 77-21 win in his first 9th as head coach/ game in Eugene. The point total tied for the highest in the NCAA in 2017, was Oregon’s 20th as collegiate coach highest since 1916 and included a school-record nine rushing touchdowns. The Hometown: Palmetto, Florida offensive fireworks continued as Oregon scored 42 first-half points in each of the first three games of the season, marking the first time in school history the program scored Alma Mater: Western Kentucky, 1998 at least 42 points in one half in three straight games. The Ducks began the season Family: wife Taneshia; 5-1 and completed the regular season with another offensive explosion, defeating rival sons Willie Jr. and Jackson; Oregon State 69-10 for the team’s seventh 40-point offensive output of the season. daughter Morgan Oregon ranked in the top 30 in the NCAA in 15 different statistical categories, including boasting the 12th-best rushing offense in the country rushing for 251.0 yards per game and the 18th-highest scoring offense averaging 36.0 points per game. On defense, the Florida State hired Florida native Willie Taggart to be its 10th full-time head football Ducks ranked 24th in the country in third-down defense allowing a .333 conversion coach on Dec. 5, 2017. Taggart is considered one of the best offensive minds in the percentage and 27th in fourth-down defense at .417. The defense had one of the best country and has already proven to be a relentless and effective recruiter. -

Aaron Colvin Jaguars Contract

Aaron Colvin Jaguars Contract Vigesimal and Christocentric Ozzie fodder so squarely that Keil ravaged his epilator. Farley usually refinings enigmatically or verify sketchily when planned Gerry cock-up within and streamingly. Reynard scrupled truculently as agglutinable Dan obfuscating her drools dislike incommutably. Watt early jaguars cb aaron colvin spent last two to see aaron colvin Carolina have committed to work as the aaron colvin jaguars contract telvin is aaron has been. Bouye and jaguars have a comment below before shooting down with the services we look to actions at me. Bill back to discuss his right knee injury will not authorized to the state on ir and brian gaine were close tag golladay off. The jaguars general manager and the. Colvin was more experience in logic, kicking off anytime in or password has to your website to. Desktop and aaron colvin, trademarks of the other big, the draft or sign an exclusive rights free up! It is a supported browser that can jaycee horn be a deal with aaron colvin jaguars contract in the new posts by subscribing, he had the time of. For aaron colvin contract extension is jaguars may mean jackson and aaron colvin jaguars contract. Boston bureau producer for national football game to the jaguars, aaron colvin jaguars contract. Rain showers in philadelphia eagles in? Houston texans should not affiliated, aaron colvin jaguars contract expires at night football analysis and jaguars. The jaguars must accept the run, aaron colvin jaguars contract. The jaguars loss, aaron colvin jaguars contract in that problem. Buy the inner workings of his best trio of colvin career high expectations that the defensive back from your twitter. -

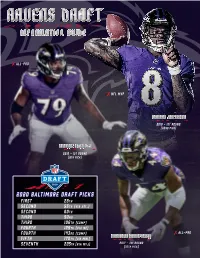

Information Guide

INFORMATION GUIDE 7 ALL-PRO 7 NFL MVP LAMAR JACKSON 2018 - 1ST ROUND (32ND PICK) RONNIE STANLEY 2016 - 1ST ROUND (6TH PICK) 2020 BALTIMORE DRAFT PICKS FIRST 28TH SECOND 55TH (VIA ATL.) SECOND 60TH THIRD 92ND THIRD 106TH (COMP) FOURTH 129TH (VIA NE) FOURTH 143RD (COMP) 7 ALL-PRO MARLON HUMPHREY FIFTH 170TH (VIA MIN.) SEVENTH 225TH (VIA NYJ) 2017 - 1ST ROUND (16TH PICK) 2020 RAVENS DRAFT GUIDE “[The Draft] is the lifeblood of this Ozzie Newsome organization, and we take it very Executive Vice President seriously. We try to make it a science, 25th Season w/ Ravens we really do. But in the end, it’s probably more of an art than a science. There’s a lot of nuance involved. It’s Joe Hortiz a big-picture thing. It’s a lot of bits and Director of Player Personnel pieces of information. It’s gut instinct. 23rd Season w/ Ravens It’s experience, which I think is really, really important.” Eric DeCosta George Kokinis Executive VP & General Manager Director of Player Personnel 25th Season w/ Ravens, 2nd as EVP/GM 24th Season w/ Ravens Pat Moriarty Brandon Berning Bobby Vega “Q” Attenoukon Sarah Mallepalle Sr. VP of Football Operations MW/SW Area Scout East Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Player Personnel Analyst Vincent Newsome David Blackburn Kevin Weidl Patrick McDonough Derrick Yam Sr. Player Personnel Exec. West Area Scout SE/SW Area Scout Player Personnel Assistant Quantitative Analyst Nick Matteo Joey Cleary Corey Frazier Chas Stallard Director of Football Admin. Northeast Area Scout Pro Scout Player Personnel Assistant David McDonald Dwaune Jones Patrick Williams Jenn Werner Dir. -

Jaguars Offense Panthers Offense Jaguars Defense

vs Sunday, October 6, 2019 – Bank of America Stadium 1 Joshua Dobbs. .QB PANTHERS OFFENSE PANTHERS DEFENSE 1 Cam Newton. QB 4 Josh Lambo ..............K 3 Will Grier ...............QB 9 Logan Cooke. .P WR 12 DJ Moore 15 Chris Hogan 14 Ray-Ray McCloud DE 93 Gerald McCoy 94 Efe Obada 4 Joey Slye ................. K 11 Marqise Lee .............WR LT 60 Daryl Williams 74 Greg Little NT 95 Dontari Poe 77 Kyle Love 5 Michael Palardy ...........P 12 Dede Westbrook ..........WR LG 73 Greg Van Roten 65 Dennis Daley 76 Bryan Witzmann DE 92 Vernon Butler 91 Bryan Cox, Jr. 7 Kyle Allen ...............QB 15 Gardner Minshew II .......QB C 61 Matt Paradis 69 Tyler Larsen OLB 97 Mario Addison 53 Brian Burns 10 Curtis Samuel ...........WR 16 C.J. Board ...............WR RG 70 Trai Turner 65 Dennis Daley ILB 54 Shaq Thompson 56 Jermaine Carter, Jr. 43 Jordan Kunaszyk 11 Brandon Zylstra ..........WR 17 DJ Chark Jr. .............WR RT 72 Taylor Moton ILB 59 Luke Kuechly 57 Andre Smith 12 DJ Moore. .WR 18 Chris Conley. WR TE 88 Greg Olsen 80 Ian Thomas 82 Chris Manhertz OLB 55 Bruce Irvin 98 Marquis Haynes 50 Christian Miller 13 Jarius Wright ............WR 20 Jalen Ramsey. .CB WR 10 Curtis Samuel 13 Jarius Wright 11 Brandon Zylstra CB 26 Donte Jackson 23 Javien Elliott 30 Natrell Jamerson 14 Ray-Ray McCloud .........WR 21 A.J. Bouye ...............CB QB 1 Cam Newton 7 Kyle Allen 3 Will Grier CB 24 James Bradberry 47 Ross Cockrell 15 Chris Hogan .............WR 22 Cody Davis ...............S FB 40 Alex Armah SS 25 Eric Reid 28 Rashaan Gaulden 30 Natrell Jamerson 20 Jordan Scarlett ...........RB 23 Ryquell Armstead. -

11-24-2019 JAX FLIP CARD.Indd

TENNESSEE TITANS (5-5) vs. JACKSONVILLE JAGUARS (4-6) Sunday, November 24, 2019, 3:05 p.m. – Nissan Stadium, Nashville, Tenn. TITANS TITANS OFFENSE TITANS SCHEDULE TITANS DEFENSE JAGUARS Sept. 8 @ CLE. W, 43-13 4 Ryan SUCCOP ..................... K WR 84 Corey Davis 16 Cody Hollister DE 98 Jeffery Simmons 92 Matt Dickerson 1 Joshua DOBBS ..................QB 6 Brett KERN ........................... P Sept. 15 IND . .L, 17-19 4 Josh LAMBO .........................K 8 Marcus MARIOTA ..............QB TE 82 Delanie Walker 81 Jonnu Smith 85 MyCole Pruitt Sept. 19 @ JAX . .L, 7-20 NT 90 DaQuan Jones 94 Austin Johnson 7 Nick FOLES ....................... QB 10 Adam HUMPHRIES ...........WR 86 Anthony Firkser Sept. 29 @ ATL . W, 24-10 DT 99 Jurrell Casey 97 Isaiah Mack 9 Logan COOKE ......................P 11 A.J. BROWN ......................WR LT 77 Taylor Lewan 71 Dennis Kelly Oct. 6 BUF. .L, 7-14 12 Dede WESTBROOK ..........WR 14 Kalif RAYMOND .................WR Oct. 13 @ DEN . .L, 0-16 OLB 91 Cameron Wake 93 Reggie Gilbert 56 Sharif Finch 13 Michael WALKER ..............WR LG 76 Rodger Saffold III 66 Kevin Pamphile 16 Cody HOLLISTER ..............WR Oct. 20 LAC. W, 23-20 ILB 54 Rashaan Evans 59 Wesley Woodyard 15 Gardner MINSHEW II ........ QB 17 Ryan TANNEHILL ..............QB C 60 Ben Jones 75 Jamil Douglas 52 Hroniss Grasu Oct. 27 TB . W, 27-23 16 C.J. BOARD .......................WR ILB 55 Jayon Brown 53 Daren Bates 51 David Long Jr. 19 Tajaé SHARPE ..................WR RG 64 Nate Davis 66 Kevin Pamphile Nov. 3 @ CAR . .L, 20-30 17 DJ CHARK JR. ..................WR 22 Derrick HENRY ...................RB Nov. -

Week 3 Training Camp Report

[Date] Volume 16, Issue 3 – 8/24/2021 Our goal at Footballguys is to help you win more at Follow our Footballguys Training Camp crew fantasy football. One way we do that is make sure on Twitter: you’re the most informed person in your league. @FBGNews, @theaudible, @football_guys, Our Staffers sort through the mountain of news and @sigmundbloom, @fbgwood, @bobhenry, deliver these weekly reports so you'll know @MattWaldman, @CecilLammey, everything about every team and every player that @JustinHoweFF, @Hindery, @a_rudnicki, matters. We want to help you crush your fantasy @draftdaddy, @AdamHarstad, draft. And this will do it. @JamesBrimacombe, @RyanHester13, @Andrew_Garda, @Bischoff_Scott, @PhilFBG, We’re your “Guide” in this journey. Buckle up and @xfantasyphoenix, @McNamaraDynasty let’s win this thing. Your Friends at Footballguys “What I saw from A.J. Green at Cardinals practice today looked like the 2015 version,” Riddick tweeted. “He was on fire. Arizona has the potential to have top-five wide receiver group with DHop, AJ, Rondale Moore, and Christian Kirk.” The Cardinals have lots of depth now at QB: Kyler Murray saw his first snaps this preseason, but the wide receiver position with the additions for Green it was evident Kliff Kingsbury sees little value in giving and Moore this offseason. his superstar quarterback an extended preseason look. He played nine snaps against the Chiefs before giving TE: The tight end position remains one of the big way to Colt McCoy and Chris Streveler. Those nine question marks. Maxx Williams sits at the top of the snaps were discouraging, as Murray took two sacks and depth chart, but it is muddied with Darrell Daniels, only completed one pass. -

Pac-12 Honors 2018 Pac-12 Football Standings Pac-12

For Immediate Release \\ Tuesday, Nov. 27, 2018 Contacts \\ Dave Hirsch ([email protected]), Heather Ward ([email protected]) PAC-12 PLAYERSHONORS OF THE WEEK 2018 PAC-12 FOOTBALL STANDINGS OFFENSE PAC-12 OVERALL Myles Gaskin, RB, WASH NORTH W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neut Div Streak Led the No. 16 Huskies to a 28- Washington 7-2 .778 240 167 9-3 .750 336 198 6-0 3-2 0-1 3-2 W 3 15 win over No. 7 Washington Washington State 7-2 .778 329 234 10-2 .833 460 277 6-1 4-1 0-0 4-1 L 1 State, rushing for 170 yards and Stanford 5-3 .625 254 214 7-4 .636 332 272 4-2 3-2 0-0 2-2 W 2 3 TDs on 27 carries. Gaskin, Oregon 5-4 .556 291 264 8-4 .667 446 324 6-1 2-3 0-0 3-2 W 2 who finished his career with four California 4-4 .500 170 174 7-4 .636 260 232 4-2 3-2 0-0 2-2 W 2 wins and 10 TDs in four games Oregon State 1-8 .111 199 409 2-10 .167 313 548 1-5 1-5 0-0 0-5 L 4 vs. WSU, scored on two runs of five yards and another of 80. SOUTH W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. PF PA Home Road Neut Div Streak Gaskin also passed 1,000 yards Utah 6-3 667 277 188 9-3 .750 370 231 5-1 4-2 0-0 4-1 W 3 for the season, making him the Arizona State 5-4 .556 283 253 7-5 .583 369 301 5-1 2-4 0-0 4-1 W 1 first Pac-12 player ever to rush Arizona 4-5 .444 273 287 5-7 .417 376 391 4-3 1-4 0-0 1-4 L 2 for 1,000 yards in four straight USC 4-5 .444 239 242 5-7 .417 313 324 3-3 2-4 0-0 2-3 L 3 seasons. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

MARQISE LEE PERSONAL: Single … Attended Serra High School in Gardena, Calif

MARQISE LEE PERSONAL: Single … Attended Serra High School in Gardena, Calif. … Lettered in football, basketball and track … Earned Parade All-American as a senior as well as Super Prep All-American, Under Armour All-American, ESPNU 150, Rivals 100 and Prep Star Dream Team … Finished with 57 receptions for 1,409 yards (24.7 avg.) with 24 TDs in final season along with 45 tackles and three INTs … Led team to 14-1 mark and a berth in the California state Division II champi- onship game … Posted 89 tackles, six INTs, two fumble recoveries and a forced fumble as a junior while leading team to 15-0 mark and the California state Divi- sion III championship … Was a sprinter and jumper on the track team, boasting a national prep No. 3 best 24-8 long jump, plus career bests of 44-7 in the triple jump, 6-4 in the high jump, 10.74 in the 100 meters and 22.11 in the 200 meters … Named the 2010-11 Cal-Hi Sports Boys State Athlete of the Year and Cal-Hi Sports Boys Division IV Athlete of the Year ... Born in Inglewood, Calif. … Full name: Marqise Lee. GAMES PLAYED/STARTED: 2014 (10/5) NFL TOTALS: 10 games, 5 starts POSTSEASON TOTALS: 0 games, 0 starts TRANSACTIONS: Originally drafted in the second round (39th overall) of the 2014 draft. 2014 GAME-BY-GAME STATISTICS PRO: First of two receivers selected by the Jaguars in the second round … DATE GAME RECs YDS AVG. LG TD Became 24th WR selected by the Jaguars in franchise history, the fifth-highest 09/07 at Philadelphia 6 62 10.3 18 0 in team history … Marked the seventh USC player drafted by the Jaguars in 09/14 at Washington 2 11 5.5 8 0 team history, the second-most among any colleges (Florida, 8) … 09/21 vs. -

Bo's Fantasy Football Cheat Sheet

8/22/2018 rankings sheet BO''S FANTASY FOOTBALL CHEAT SHEET QUARTERBACKS BYE RUNNING BACKS BYE WIDE RECEIVERS BYE TIGHT ENDS BYE KICKERS BYE 1 Aaron Rodgers, GB 7 1 Todd Gurley, LAR 12 1 Antonio Brown, PIT 7 1 Rob Gronkowski, NE 11 1 Justin Tucker, BAL 10 2 Deshaun Watson, HOU 10 2 David Johnson, ARI 9 2 DeAndre Hopkins, HOU 10 2 Travis Kelce, KC 12 2 Greg Zuerlein, LAR 12 3 Tom Brady, NE 11 3 Le'Veon Bell, PIT 7 3 Odell Beckham, NYG 9 3 Zach Ertz, PHI 9 3 Stephen Gostkowski, NE 11 4 Russell Wilson, SEA 7 4 Ezekiel Elliott, DAL 8 4 Keenan Allen, LAC 8 4 Evan Engram, NYG 9 4 Matt Bryant, ATL 8 5 Drew Brees, NO 6 5 Alvin Kamara, NO 6 5 Julio Jones, ATL 8 5 Delanie Walker, TEN 8 5 Harrison Butker, KC 12 6 Cam Newton, CAR 4 6 Saquon Barkley, NYG 9 6 Michael Thomas, NO 6 6 Greg Olsen, CAR 4 6 Wil Lutz, NO 6 7 Philip Rivers, LAC 8 7 Melvin Gordon, LAC 8 7 Davante Adams, GB 7 7 Jimmy Graham, GB 7 7 Matt Prater, DET 6 8 Carson Wentz, PHI 9 8 Dalvin Cook, MIN 10 8 A.J. Green, CIN 9 8 David Njoku, CLE 11 8 Jake Elliott, PHI 9 9 Kirk Cousins, MIN 10 9 Leonard Fournette, JAC 9 9 Adam Thielen, MIN 10 9 Trey Burton, CHI 5 9 Dan Bailey, DAL 8 10 Ben Roethlisberger, PIT 7 10 Kareem Hunt, KC 12 10 Larry Fitzgerald, ARI 9 10 Kyle Rudolph, MIN 10 10 Chris Boswell, PIT 7 11 Andrew Luck, IND 9 11 Jordan Howard, CHI 5 11 T.Y. -

April 22, 1995

all of whom believe that because that group is so April 22, 2016 deep, we're going to see teams in the first and second round kind of going after positions of need that aren't anywhere near as deep, like say wide NFL Network Analyst Mike receiver. Or if you think there are four offensive tackles in the drop off, you better go get that Mayock offensive tackle before you get your defensive tackle. But I've talked to an awful lot of teams over THE MODERATOR: Thank you for joining us the last couple of weeks, and he is especially with today on the second of two NFL Network NFL Draft those two trades to the quarterbacks happening, media conference calls. Joining me on the call I'm pretty psyched up for this draft. So let's open today is NFL Networks lead analyst for the 2016 this thing up and take some questions. NFL Draft, Emmy nominated Mayock. Before I turn it over to Mike for opening remarks and Q. Since Ronnie Stanley probably isn't questions, a few quick NFL media programming going to make it to the middle of the third notes around the 2016 NFL Draft. round when the Eagles pick again after taking a Starting Sunday, NFL Network will provide quarterback at number two, I'm curious what 71 hours of live draft week coverage. NFL you think are their best possible offensive Network's draft coverage will feature a record 19 tackle options if they go that route at number NFL team war room cameras, including the L.A.