Calvin Coolidge's Afro-American Connection Maceo Crenshaw Dailey Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits of “Diversity” Where Affirmative Action Was About Compensatory Justice, Diversity Is Meant to Be a Shared Benefit

The Limits of “Diversity” Where affirmative action was about compensatory justice, diversity is meant to be a shared benefit. But does the rationale carry weight? By Kelefa Sanneh, THE NEW YORKER, October 9, 2017 This summer, the Times reported that, under President Trump, the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice had acquired a new focus. The division, which was founded in 1957, during the fight over school integration, would now be going after colleges for discriminating against white applicants. The article cited an internal memo soliciting staff lawyers for “investigations and possible litigation related to intentional race-based discrimination in college and university admissions.” But the memo did not explicitly mention white students, and a spokesperson for the Justice Department charged that the story was inaccurate. She said that the request for lawyers related specifically to a complaint from 2015, when a number of groups charged that Harvard was discriminating against Asian-American students. In one sense, Asian-Americans were overrepresented at Harvard: in 2013, they made up eighteen per cent of undergraduates, despite being only about five per cent of the country’s population. But at the California Institute of Technology, which does not employ racial preferences, Asian- Americans made up forty-three per cent of undergraduates—a figure that had increased by more than half over the previous two decades, while Harvard’s percentage had remained relatively flat. The plaintiffs used SAT scores and other data to argue that administrators had made it “far more difficult for Asian-Americans than for any other racial and ethnic group of students to gain admission to Harvard.” They claimed that Harvard, in its pursuit of racial parity, was not only rewarding black and Latino students but also penalizing Asian-American students—who were, after all, minorities, too. -

Survey of Current Business October 1924

MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO COMMERCE REPORTS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE WASHINGTON SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS OCTOBER, 1924 No. 38 COMPILED BY BUREAU OF THE CENSUS BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE BUREAU OF STANDARDS IMPORTANT NOTICE In addition to figures given from Government sources9 there are also incorporated for completeness of service figures from other sources generally accepted by the trades, the authority and responsibility for which are noted in the "Sources of data9' at the end of this number Subscription price of the SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS is* $1.50 a year; single copies (monthly), 10 cents, quarterly issues, 20 cents. Foreign subscriptions, $2.25; single copies (monthly issues) including postage, 14 cents, quarterly issues, 31 cents. Subscription price of COMMERCE REPORTS is $4 a year; with the Survey, $5.50 a year. Make remittances only to Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C, by postal money order, express order, or New York draft. Currency at sender's risk. Postage stamps or foreign money not accepted. ^v - WASHINQTON : GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1994 INTRODUCTION The SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS is designed to period has been chosen. In a few cases other base present each month a picture of the business situation periods are used for special reasons. In all cases the by setting forth the principal facts regarding the vari- base period is clearly indicated. ous lines of trade and industry. At quarterly intervals The relative numbers are computed by allowing the detailed tables are published giving, for each item, monthly average for the base year or period to equal monthly figures for the past two years and yearly com- 100. -

Untimely Meditations: Reflections on the Black Audio Film Collective

8QWLPHO\0HGLWDWLRQV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH%ODFN$XGLR )LOP&ROOHFWLYH .RGZR(VKXQ Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 19, Summer 2004, pp. 38-45 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\'XNH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nka/summary/v019/19.eshun.html Access provided by Birkbeck College-University of London (14 Mar 2015 12:24 GMT) t is no exaggeration to say that the installation of In its totality, the work of John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Handsworth Songs (1985) at Documentall introduced a Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and new audience and a new generation to the work of the Trevor Mathison remains terra infirma. There are good reasons Black Audio Film Collective. An artworld audience internal and external to the group why this is so, and any sus• weaned on Fischli and Weiss emerged from the black tained exploration of the Collective's work should begin by iden• cube with a dramatically expanded sense of the historical, poet• tifying the reasons for that occlusion. Such an analysis in turn ic, and aesthetic project of the legendary British group. sets up the discursive parameters for a close hearing and viewing The critical acclaim that subsequently greeted Handsworth of the visionary project of the Black Audio Film Collective. Songs only underlines its reputation as the most important and We can locate the moment when the YBA narrative achieved influential art film to emerge from England in the last twenty cultural liftoff in 1996 with Douglas Gordon's Turner Prize vic• years. It is perhaps inevitable that Handsworth Songs has tended tory. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Federal Reserve Bulletin October 1924

FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN OCTOBER, 1924 ISSUED BY THE FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD AT WASHINGTON Crop Production and Prices in 1924 Business Conditions in the United States World Wheat Crop and International Trade WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1924 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD Ex officio members: D. R. CRISSINGKR, Governor. A. W. MELLON, EDMUND PLATT, Vice Governor. Secretary of the Treasury, Chairman. ,ADOLPH C. MILLER. CHARLES S. HAMLIN. HENRY M. DAWES, GEORGE R. JAMES. Comptroller of the Currency. EDWARD H. CUNNINGHAM. WALTER L. EDDY, Secretary. WALTER WYATT, General Counsel. J. C. NOELL, Assistant Secretary. WALTER W. STEWART, W. M. IMLAY, Fiscal Agent. Director, Division of Research and Statistics. J. F. HERSON, Chief, Division of Examination, and Chief Federal E. A. GOLDENWEISER, Statistician. Reserve Examiner. 1 E. L. SMEAD, Chief, Division of Bank Operations., FEDERAL ADVISORY COUNCIL District No. 1 (BOSTON) CHAS. A. MORSS. District No. 2 (NEW YORK) . PAUL M. WARBURG, President. District No. 3 (PHILADELPHIA) L. L. RUE. District No. 4 (CLEVELAND) C. E. SULLIVAN. District NO. 5 (RICHMOND) JOHN M. MILLER, Jr. District No. 6 (ATLANTA) OSCAR WELLS. District NO. 7 (CHICAGO) .' JOHN J. MITCHELL. District NO. 8 (ST. LOUIS) FESTUS J. WADE. District NO. 9 (MINNEAPOLIS) G. H. PRINCE. District No. 10 (KANSAS CITY) E. F. SWINNEY, Vice President. DistrictNo.il (DALLAS) -- --- W. M. MCGREGOR. District No. 12 (SAN FRANCISCO) D. W. TWOHY. II Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis OFFICERS OF FEDERAL RESERVE BANKS Federal Reserve Bank of— Chairman Governor Deputy governor Cashier Boston Frederic H. -

OBJECTS Compiled in Partnership with Wiley College

Black History Month – Impromptu Prompts OBJECTS Compiled in partnership with Wiley College Carbon Filament Inventor and engineer Lewis Latimer was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts, on September 4, 1848. He collaborated with science greats Hiram Maxim and Thomas Edison. One of Latimer’s greatest inventions was the carbon filament, a vital component of the light bulb. His inventions didn’t stop there. Working with Alexander Graham Bell, Latimer helped draft the patent for Bell’s design of the telephone. This genius also designed an improved railroad car bathroom and an early air conditioning unit. So the next time you’re escaping a hot day inside your cool house, don’t forget to thank Lewis Latimer! https://thinkgrowth.org/14-black-inventors-you-probably-didnt-know-about-3c0702cc63d2 National Speech & Debate Association © 2018 | 1 Super Soaker Did you ever enjoy water gun fights as a kid? Well, meet Lonnie Johnson, the man that gave us the most famous water gun—the Super Soaker. Lonnie wasn’t a toymaker; he actually was an aerospace engineer for NASA with a resume boasting a stint with the U.S. Air Force, work on the Galileo Jupiter probe and Mars Observer project, and more than 40 patents. https://thinkgrowth.org/14-black-inventors-you-probably-didnt-know-about-3c0702cc63d2 Bloodmobile Charles Drew was a physician, surgeon, and medical researcher who worked with a team at Red Cross on groundbreaking discoveries around blood transfusions. In World War II, he played a major role in developing the first large-scale blood banks and blood plasma programs. He also invented the first bloodmobile—refrigerated trucks that, to this day, safely transport stored blood to the location where it is needed most. -

Martin Luther King's Position in the Black Power Movement from 1955 to 1968 Carol Breit

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1972 Martin Luther King's position in the Black Power movement from 1955 to 1968 Carol Breit Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Breit, Carol, "Martin Luther King's position in the Black Power movement from 1955 to 1968" (1972). Honors Theses. Paper 415. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "ilill1iiiflll1if H1llfilll1ii' 3 3082 01028 5095 MARTIN LUTHER KING'S POSITION: IN THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT 'FROM 1955 to 1968 Honors Thesis For Dr. F. W, Gregory ~IniPartial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Bachelor of Arts University of Richmond Carol Breit 1972 ''For if a rnan has not discovered something that he will die for, he isn't fit to live •••• Man dies when he refuses to take a stand for that which is right. A man dies when he refuses to take a stand for that which is true. So we are going to stand up right here ••• letting the world know .. we are determined to be free~•1 From events in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, a citadel of Southern segregation practices and American rascist attitudes, the Negro Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was to be pivoted to a pedestal of national prom~nence and of international fame. By 1958 King had become the symbol of the new black revolt locally, nationally, and internationally. -

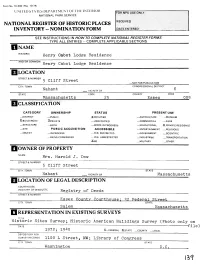

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

S Ubject L Ist N O. 44 of DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED to the MEMBERS of the COUNCIL DURING DECEMBER 1924

[DISTRIBUTED ,, e a g u e o f a t i o n s C. 5. MEMBERS OFT0TllE THE COUNCIL ] L N 1925- G en ev a , January 4 t h , 1925. S ubject L ist N o. 44 OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO THE MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL DURING DECEMBER 1924. (Prepared by the Distribution Branch.) Armaments, Reduction 0! Arms, Private manufacture of and traffic in Convention concluded September 10, 1919 at St. Germain-en-Laye for the control of traffic in arms Convention to supersede Conference, May 1925, Geneva, to prepare A Report dated December 1924 by Czechoslovak Representative (M. Benes) and resolution adopted December 8, 1924 by 32nd Council Session, fixing May 4, 1925 as date for Admissions to League C. 801. 1924. IX Germany Letter dated December r 2, 1924 from German Government (M. Stresemann) forwarding copy Text (draft) subm itted July 1924 by Temporary of its memorandum to the Governments repre Mixed Commission, of sented on the Council with a view to the elucida Letter dated October 9, 1924 from Secretary- tion of certain problems connected with Germany's General to States Members and Non- co-operation with League, announcing its satis Members of the League quoting relative faction with the replies received, except with Assembly resolution, forwarding Tempo regard to Article 16 of Covenant, and submitting rary Mixed Commission's report (A. 16. detailed statement of its apprehensions with 1924) containing above-mentioned draft and regard to this article minutes of discussion of its Article 9, and the report of 3rd Commission to Assembly C. -

4 the AMERICAN and BRITISH CULTURAL APPROACHES The

4 THE AMERICAN AND BRITISH CULTURAL APPROACHES HOW DIFFERENT WAS Japan's cultural approach from those of the United States and Great Britain in the 1920S? Was the same pattern of Sino Japanese interaction reflected in Sino-American and Sino-British interaction during this period? In analyzing the American situation, the chapter first focuses on Sino-American interaction and then examines American views on how the remission could be best used. The British case is then examined in a similar fashion, followed by a comparison of the two ap proaches. THE AMERICAN APPROACH, 1924-1931 The Second American Remission and Sino-American Interaction In December 1908, the United States remitted a portion of its Boxer indem nity to support an educational program comprised of the Chinese Educa tional Mission and T singhua College. While this program continued into the 1920S, there were also calls for the United States to remit the remaining portion of its indemnity for similar purposes. This movement for total re mission was actively advocated by the chairman of the Senate Foreign Rela tions Committee, Henry Cabot Lodge. With the backing of the State De partment, Lodge introduced a resolution for total remission in May 1921. Although the resolution was passed by the Senate in August, it was stalled The American and British Cultural Approaches 93 in the House, whose members feared that approving such an act might en courage the European powers involved in World War I to press the United States for a. similar waiving of their war debts.l When the fear of such a linkage gradually ebbed over the next two years, Lodge re-introduced the remission resolution into Congress in December 1923.