State of Connecticut Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty Years of Surveillance for Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus In

Oliver et al. Parasites & Vectors (2018) 11:362 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2950-1 RESEARCH Open Access Twenty years of surveillance for Eastern equine encephalitis virus in mosquitoes in New York State from 1993 to 2012 JoAnne Oliver1,2*, Gary Lukacik3, John Kokas4, Scott R. Campbell5, Laura D. Kramer6,7, James A. Sherwood1 and John J. Howard1 Abstract Background: The year 1971 was the first time in New York State (NYS) that Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) was identified in mosquitoes, in Culiseta melanura and Culiseta morsitans. At that time, state and county health departments began surveillance for EEEV in mosquitoes. Methods: From 1993 to 2012, county health departments continued voluntary participation with the state health department in mosquito and arbovirus surveillance. Adult female mosquitoes were trapped, identified, and pooled. Mosquito pools were tested for EEEV by Vero cell culture each of the twenty years. Beginning in 2000, mosquito extracts and cell culture supernatant were tested by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Results: During the years 1993 to 2012, EEEV was identified in: Culiseta melanura, Culiseta morsitans, Coquillettidia perturbans, Aedes canadensis (Ochlerotatus canadensis), Aedes vexans, Anopheles punctipennis, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, Psorophora ferox, Culex salinarius, and Culex pipiens-restuans group. EEEV was detected in 427 adult mosquito pools of 107,156 pools tested totaling 3.96 million mosquitoes. Detections of EEEV occurred in three geographical regions of NYS: Sullivan County, Suffolk County, and the contiguous counties of Madison, Oneida, Onondaga and Oswego. Detections of EEEV in mosquitoes occurred every year from 2003 to 2012, inclusive. EEEV was not detected in 1995, and 1998 to 2002, inclusive. -

HEALTHINFO H E a Lt H Y E Nvironment T E a M Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE)

H aldimand-norfolk HE a LT H U N I T HEALTHINFO H e a lt H y e nvironment T E a m eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) What is eastern equine encephalitis? Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE), some- times called sleeping sickness or Triple E, is a rare but serious viral disease spread by infected mosquitoes. How is eastern equine encephalitis transmitted? The Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEv) can infect a wide range of hosts including mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians. Infection occurs through the bite of an infected mosquito. The virus itself is maintained in nature through a cycle between Culiseta melan- ura mosquitoes and birds. Culiseta mel- anura mosquitoes feed almost exclusively on birds, so they are not considered an important vector of EEEv to humans or other mammals. Transmission of EEEv to humans requires mosquito species capable of creating a “bridge” between infected birds and uninfected mammals. Other species of mosquitoes (including Coquiletidia per- Coast states. In Ontario, EEEv has been ticipate in outdoor recreational activities turbans, Aedes vexans, Ochlerotatus found in horses that reside in the prov- have the highest risk of developing EEE sollicitans and Oc. Canadensis) become ince or that have become infected while because of greater exposure to potentially infected when they feed on infected travelling. infected mosquitoes. birds. These infected mosquitoes will then occasionally feed on horses, humans Similar to West Nile virus (WNv), the People of all ages are at risk for infection and other mammals, transmitting the amount of virus found in nature increases with the EEE virus but individuals over age virus. -

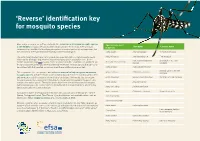

Identification Key for Mosquito Species

‘Reverse’ identification key for mosquito species More and more people are getting involved in the surveillance of invasive mosquito species Species name used Synonyms Common name in the EU/EEA, not just professionals with formal training in entomology. There are many in the key taxonomic keys available for identifying mosquitoes of medical and veterinary importance, but they are almost all designed for professionally trained entomologists. Aedes aegypti Stegomyia aegypti Yellow fever mosquito The current identification key aims to provide non-specialists with a simple mosquito recog- Aedes albopictus Stegomyia albopicta Tiger mosquito nition tool for distinguishing between invasive mosquito species and native ones. On the Hulecoeteomyia japonica Asian bush or rock pool Aedes japonicus japonicus ‘female’ illustration page (p. 4) you can select the species that best resembles the specimen. On japonica mosquito the species-specific pages you will find additional information on those species that can easily be confused with that selected, so you can check these additional pages as well. Aedes koreicus Hulecoeteomyia koreica American Eastern tree hole Aedes triseriatus Ochlerotatus triseriatus This key provides the non-specialist with reference material to help recognise an invasive mosquito mosquito species and gives details on the morphology (in the species-specific pages) to help with verification and the compiling of a final list of candidates. The key displays six invasive Aedes atropalpus Georgecraigius atropalpus American rock pool mosquito mosquito species that are present in the EU/EEA or have been intercepted in the past. It also contains nine native species. The native species have been selected based on their morpho- Aedes cretinus Stegomyia cretina logical similarity with the invasive species, the likelihood of encountering them, whether they Aedes geniculatus Dahliana geniculata bite humans and how common they are. -

ARTHROPOD MONITORING: Mosquito Studies

64 ARTHROPOD MONITORING: Mosquito Studies - Greenwoods, Summer 1995 Wi~~iam L. Butts Expanded sampling of the area inunediately adj acent to the large bog ("Cranberry Bog") for anthrophilic mosquitoes was the main focus of studies at Greenwoods. Initial plans to conduct biting/alighting sampling from a boat at selected sites around the margin of the impoundment were abandoned due to logistical difficulties. Emergent and submerged obstructions made it impossible to move about by boat at a rate that would allow for sampling at a sufficient number of sites within the hours of feeding activity. It was also evident that repeated sampling by boat would cause an unacceptable level of disruption to aquatic vegetation. A series of eight sampling sites marked with bicolored streamers was established along the west side of the bog from the point of access to the main dam northward. A similar series was laid out along the east side with three sampling stations south of the one at the dock site and four stations north of it. Biting/alighting collections were made by the author sitting for 20 minutes at each site with one forearm exposed. Mosquitoes alighting upon that arm or at other points on the body within reach of the other arm were collected by inverting a small killing vial over the mosquitoes. Sampling series were begun at approximately first light and in late evening beginning at a time estimated to terminate the series when unaided visual observation became difficult. In most instances one side of the bog was sampled in the evening and the other side the following morning. -

A Synopsis of the Mosquitoes of Missouri and Their Importance from a Health Perspective Compiled from Literature on the Subject

A Synopsis of The Mosquitoes of Missouri and Their Importance From a Health Perspective Compiled from Literature on the Subject by Dr. Barry McCauley St. Charles County Department of Community Health and the Environment St. Charles, Missouri Mark F. Ritter City of St. Louis Health Department St. Louis, Missouri Larry Schaughnessy City of St. Peters Health Department St. Peters, Missouri December 2000 at St. Charles, Missouri This handbook has been prepared for the use of health departments and mosquito control pro- fessionals in the mid-Mississippi region. It has been drafted to fill a perceived need for a single source of information regarding mosquito population types within the state of Missouri and their geographic distribution. Previously, the habitats, behaviors and known distribution ranges of mosquitoes within the state could only be referenced through consultation of several sources - some of them long out of print and difficult to find. It is hoped that this publication may be able to fill a void within the literature and serve as a point of reference for furthering vector control activities within the state. Mosquitoes have long been known as carriers of diseases, such as malaria, yellow fever, den- gue, encephalitis, and heartworm in dogs. Most of these diseases, with the exception of encephalitis and heartworm, have been fairly well eliminated from the entire United States. However, outbreaks of mosquito borne encephalitis have been known to occur in Missouri, and heartworm is an endemic problem, the costs of which are escalating each year, and at the current moment, dengue seems to be making a reappearance in the hotter climates such as Texas. -

Aedes (Ochlerotatus) Vexans (Meigen, 1830)

Aedes (Ochlerotatus) vexans (Meigen, 1830) Floodwater mosquito NZ Status: Not present – Unwanted Organism Photo: 2015 NZB, M. Chaplin, Interception 22.2.15 Auckland Vector and Pest Status Aedes vexans is one of the most important pest species in floodwater areas in the northwest America and Germany in the Rhine Valley and are associated with Ae. sticticus (Meigen) (Gjullin and Eddy, 1972: Becker and Ludwig, 1983). Ae. vexans are capable of transmitting Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEE), Western equine encephalitis virus (WEE), SLE, West Nile Virus (WNV) (Turell et al. 2005; Balenghien et al. 2006). It is also a vector of dog heartworm (Reinert 1973). In studies by Otake et al., 2002, it could be shown, that Ae. vexans can transmit porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) in pigs. Version 3: Mar 2015 Geographic Distribution Originally from Canada, where it is one of the most widely distributed species, it spread to USA and UK in the 1920’s, to Thailand in the 1970’s and from there to Germany in the 1980’s, to Norway (2000), and to Japan and China in 2010. In Australia Ae. vexans was firstly recorded 1996 (Johansen et al 2005). Now Ae. vexans is a cosmopolite and is distributed in the Holarctic, Orientalis, Mexico, Central America, Transvaal-region and the Pacific Islands. More records of this species are from: Canada, USA, Mexico, Guatemala, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria, Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden Finland, Norway, Spain, Greece, Italy, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro), Turkey, Russia, Algeria, Libya, South Africa, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Yemen, Cambodia, China, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia (Lien et al, 1975; Lee et al 1984), Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Palau, Philippines, Micronesia, New Caledonia, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, Vanuatu, Tuvalu, New Zealand (Tokelau), Australia. -

American Aedes Vexans Mosquitoes Are Competent Vectors of Zika Virus

Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg., 96(6), 2017, pp. 1338–1340 doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0963 Copyright © 2017 by The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene American Aedes vexans Mosquitoes are Competent Vectors of Zika Virus Alex Gendernalik,1 James Weger-Lucarelli,1 Selene M. Garcia Luna,1 Joseph R. Fauver,1 Claudia Rückert,1 Reyes A. Murrieta,1 Nicholas Bergren,1 Demitrios Samaras,1 Chilinh Nguyen,1 Rebekah C. Kading,1 and Gregory D. Ebel1* 1Arthropod-Borne and Infectious Diseases Laboratory, Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado Abstract. Starting in 2013–2014, the Americas have experienced a massive outbreak of Zika virus (ZIKV) which has now reached at least 49 countries. Although most cases have occurred in South America and the Caribbean, imported and autochthonous cases have occurred in the United States. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes are known vectors of ZIKV. Little is known about the potential for temperate Aedes mosquitoes to transmit ZIKV. Aedes vexans has a worldwide distribution, is highly abundant in particular localities, aggressively bites humans, and is a competent vector of several arboviruses. However, it is not clear whether Ae. vexans mosquitoes are competent to transmit ZIKV. To determine the vector competence of Ae. vexans for ZIKV, wild-caught mosquitoes were exposed to an infectious bloodmeal containing a ZIKV strain isolated during the current outbreak. Approximately 80% of 148 mos- quitoes tested became infected by ZIKV, and approximately 5% transmitted infectious virus after 14 days of extrinsic incubation. These results establish that Ae. vexans are competent ZIKV vectors. -

Mosquitoes in Ohio

Mosquitoes in Ohio There are about 60 different species of mosquito in Ohio. Several of them are capable of transmitting serious, possibly even fatal diseases, such as mosquito-borne encephalitis and malaria to humans. Even in the absence of disease transmission, mosquito bites can result in allergic reactions producing significant discomfort and itching. In some cases excessive scratching can lead to bleeding, scabbing, and possibly even secondary infection. Children are very susceptible to this because they find it difficult to stop scratching. Frequently, they are outside playing and do not realize the extent of their exposure until it is too late. Female mosquitoes can produce a painful bite during feeding, and, in excessive numbers, can inhibit outdoor activities and lower property values. Mosquitoes can be a significant burden on animals, lowering productivity and efficiency of farm animals. Life Cycle Adult mosquitoes are small, fragile insects with slender bodies; one pair of narrow wings (tiny scales are attached to wing veins); and three pairs of long, slender legs. They vary in length from 3/16 to 1/2 inch. Mosquitoes have an elongate "beak" or piercing proboscis. Eggs are elongate, usually about 1/40 inch long, and dark brown to black near hatching. Larvae or "wigglers" are filter feeders that move with an S-shaped motion. Larvae undergo four growth stages called instars before they molt into the pupa or "tumbler" stage. Pupae are comma-shaped and non-feeding and appear to tumble through the water when disturbed. 1 Habits and Diseases Carried Mosquitoes may over-winter as eggs, fertilized adult females or larvae. -

Local Persistence of Novel Regional Variants of La Crosse Virus in the Northeast United States

Local persistence of novel regional variants of La Crosse virus in the Northeast United States Gillian Eastwood ( [email protected] ) University of Leeds https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5574-7900 John J Shepard Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Michael J Misencik Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Theodore G Andreadis Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Philip M Armstrong Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Research Keywords: Arbovirus, Vector, Mosquito species, La Crosse virus, Pathogen persistence, Genetic distinction, Public Health risk Posted Date: October 14th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-61059/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on November 11th, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04440-4. Page 1/16 Abstract Background: La Crosse virus [LACV] (genus Orthobunyavirus, family Peribunyaviridae) is a mosquito- borne virus that causes pediatric encephalitis and accounts for 50-150 human cases annually in the USA. Human cases occur primarily in the Midwest and Appalachian regions whereas documented human cases occur very rarely in the northeastern USA. Methods: Following detection of a LACV isolate from a eld-collected mosquito in Connecticut during 2005, we evaluated the prevalence of LACV infection in local mosquito populations and genetically characterized virus isolates to determine whether the virus is maintained focally in this region. Results: During 2018, we detected LACV in multiple species of mosquitoes, including those not previously associated with the virus. We also evaluated the phylogenetic relationship of LACV strains isolated from 2005-2018 in Connecticut and found that they formed a genetically homogeneous clade that was most similar to strains from New York State. -

Diptera: Culicidae) in the Laboratory Sara Marie Erickson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2005 Infection and transmission of West Nile virus by Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory Sara Marie Erickson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Erickson, Sara Marie, "Infection and transmission of West Nile virus by Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory" (2005). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 18773. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/18773 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Infection and transmission of West Nile virus by Ochlerotatus triseriatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in the laboratory by Sara Marie Erickson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Entomology Program of Study Committee: Wayne A. Rowley, Major Professor Russell A. Jurenka Kenneth B. Platt Marlin E. Rice Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2005 Copyright © Sara Marie Erickson, 2005. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Sara Marie Erickson has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy lll TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES lV ABSTRACT v CHAPTER 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION Thesis organization 1 Literature review 1 References 18 CHAPTER 2. -

Linking Bird and Mosquito Data to Assess Spatiotemporal West Nile Virus Risk in Humans

EcoHealth https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-019-01393-8 Ó 2019 EcoHealth Alliance Original Contribution Linking Bird and Mosquito Data to Assess Spatiotemporal West Nile Virus Risk in Humans Benoit Talbot ,1 Merlin Caron-Le´vesque,1 Mark Ardis,2 Roman Kryuchkov,1 and Manisha A. Kulkarni1 1School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Room 217A, 600 Peter Morand Crescent, Ottawa, ON K1G 5Z3, Canada 2GDG Environnement, Trois-Rivie`res, QC, Canada Abstract: West Nile virus (WNV; family Flaviviridae) causes a disease in humans that may develop into a deadly neuroinvasive disease. In North America, several peridomestic bird species can develop sufficient viremia to infect blood-feeding mosquito vectors without succumbing to the virus. Mosquito species from the genus Culex, Aedes and Ochlerotatus display variable host preferences, ranging between birds and mammals, including humans, and may bridge transmission among avian hosts and contribute to spill-over transmission to humans. In this study, we aimed to test the effect of density of three mosquito species and two avian species on WNV mosquito infection rates and investigated the link between spatiotemporal clusters of high mosquito infection rates and clusters of human WNV cases. We based our study around the city of Ottawa, Canada, between the year 2007 and 2014. We found a large effect size of density of two mosquito species on mosquito infection rates. We also found spatiotemporal overlap between a cluster of high mosquito infection rates and a cluster of human WNV cases. Our study is innovative because it suggests a role of avian and mosquito densities on mosquito infection rates and, in turn, on hotspots of human WNV cases. -

Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infection in Cats

Current Feline Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Cats Thank You to Our Generous Sponsors: Printed with an Education Grant from IDEXX Laboratories. Photomicrographs courtesy of Bayer HealthCare. © 2014 American Heartworm Society | PO Box 8266 | Wilmington, DE 19803-8266 | E-mail: [email protected] Current Feline Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis) Infection in Cats (revised October 2014) CONTENTS Click on the links below to navigate to each section. Preamble .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 EPIDEMIOLOGY ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Figure 1. Urban heat island profile. BIOLOGY OF FELINE HEARTWORM INFECTION .................................................................................................. 3 Figure 2. The heartworm life cycle. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF FELINE HEARTWORM DISEASE ................................................................................... 5 Figure 3. Microscopic lesions of HARD in the small pulmonary arterioles. Figure 4. Microscopic lesions of HARD in the alveoli. PHYSICAL DIAGNOSIS ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Clinical