Exploring the Implications of Queer Representation in Film and Television on Social Change Maya S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars

Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Pretty Little Liars Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead. Benjamin Franklin How It All Started Imagine it’s a couple of years ago, the summer between seventh and eighth grade. You’re tan from lying out next to your rock-lined pool, you’ve got on your new Juicy sweats (remember when everybody wore those?), and your mind’s on your crush, the boy who goes to that other prep school whose name we won’t mention and who folds jeans at Abercrombie in the mall. You’re eating your Cocoa Krispies just how you like ’em – doused in skim milk – and you see this girl’s face on the side of the milk carton. MISSING. She’s cute – probably cuter than you – and has a feisty look in her eyes. You think, Hmm, maybe she likes soggy Cocoa Krispies too. And you bet she’d think Abercrombie boy was a hottie as well. You wonder how someone so . well, so much like you went missing. You thought only girls who entered beauty pageants ended up on the sides of milk cartons. Well, think again. Aria Montgomery burrowed her face in her best friend Alison DiLaurentis’s lawn. ‘Delicious,’ she murmured. ‘Are you smelling the grass?’ Emily Fields called from behind her, pushing the door of her mom’s Volvo wagon closed with her long, freckly arm. ‘It smells good.’ Aria brushed away her pink-striped hair and breathed in the warm early-evening air. ‘Like summer.’ Emily waved ’bye to her mom and pulled up the blah jeans that were hanging on her skinny hips. -

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

Resource Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children

A PrActitioner’s resource Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A Practitioner’s Resource Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children was prepared by Caitlin Ryan, PhD, ACSW, Director of the Family Acceptance Project at San Francisco State University under contract number HHSP233201200519P for SAMHSA, HHS. DISCLAIMER The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA or HHS. PUBLIC DOMAIN NOTICE All materials appearing in this publication are in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied with- out permission from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. The publication may not be repro- duced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA. ELECTRONIC ACCESS This publication may be downloaded or ordered at http://store.samhsa.gov/. Or call SAMHSA at 1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726-4727) (English and Español). RECOMMENDED CITATION Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, A Practitioner’s Resource Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. HHS Publication No. PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. Table of Contents Introduction 2 Critical Role of Families in Reducing Risk & Promoting Well-Being 4 Helping Families Decrease Risk & Increase Well-Being for Their LGBT Children 8 Increasing Family Support: How to Help Right Now 11 Resources for Practitioners and Families 12 Endnotes 13 References 14 Introduction ince the early 1990s, young people have increasingly their LGBT children. So few practitioners tried to engage or been coming out or identifying as lesbian, gay, and work with these families (Ryan & Chen-Hayes, 2013). -

Tick-Tock, B**Ches”

CREATED BY I. Marlene King BASED ON THE BOOKS BY Sara Shepard EPISODE 7.01 “Tick-Tock, B**ches” In a desperate race to save one of their own, the girls must decide whether to hand over evidence of Charlotte's real murderer to "Uber A." WRITTEN BY: I. Marlene King DIRECTED BY: Ron Lagomarsino ORIGINAL BROADCAST: June 21, 2016 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. EPISODE CAST Troian Bellisario ... Spencer Hastings Ashley Benson ... Hanna Marin Tyler Blackburn ... Caleb Rivers Lucy Hale ... Aria Montgomery Ian Harding ... Ezra Fitz Shay Mitchell ... Emily Fields Andrea Parker ... Mary Drake Janel Parrish ... Mona Vanderwaal Sasha Pieterse ... Alison Rollins Keegan Allen ... Toby Cavanaugh Huw Collins ... Dr. Elliott Rollins Lulu Brud ... Sabrina Ray Fonseca ... Bartender P a g e | 1 1 00:00:08,509 --> 00:00:10,051 How could we let this happen? 2 00:00:11,512 --> 00:00:12,972 Oh, my God, poor Hanna. 3 00:00:13,012 --> 00:00:14,807 Try to remember that it's what she'd want. 4 00:00:16,684 --> 00:00:19,561 No, I don't know if I can live with this. 5 00:00:19,603 --> 00:00:21,522 I mean, how can we bury.. 6 00:00:23,064 --> 00:00:27,027 - There has to be another way. -

Best Practice Highlights

Best Practice Highlights Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and people who may be questioning their sexual orientation or sexual identity (LGBTQ) Prepared by Robert Paul Cabaj, M.D. The LGBTQ Population There really is no single LGBTQ community, rather a very diverse population that comes from all racial, ethnic, cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic backgrounds. People who are LGBTQ may move to urban areas, if they can, where there may be a sense of greater acceptance and personal safety. It is very difficult to know the percentage of people who identify as LGBTQ. Stigma and the fear of biases contribute to an underreporting of actual sexual orientation. Some people may also self-identify one way even if their internal desires or sexual behavior imply a different orientation. Identify issues may be especially pronounced for LBGTQ people from particular racial and ethnic minority groups. Significant History – Events which influenced the community and contextualize assessment and treatment Understanding the history of the LGBTQ community both in American society and within the profession of psychiatry is essential in bringing context to treatment. Some major milestones have contributed to the civil rights of LGBTQ people and to greater acceptance. First, the Stonewall riots of 1969 have become the historic launching point for gay rights. In 2003, the Supreme Count struck down sodomy laws across the county with their decision in Lawrence vs. Texas. In 2013, the Supreme Court decision on United States vs. Windsor led to the same sex couple being allowed to share the same federal benefits as opposite sex couples, ending the Defense of Marriage Act. -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

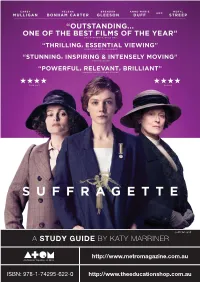

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

Makers: Women in Hollywood

WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OVERVIEW: MAKERS: Women In Hollywood showcases the women of showbiz, from the earliest pioneers to present-day power players, as they influence the creation of one of the country’s biggest commodities: entertainment. In the silent movie era of Hollywood, women wrote, directed and produced, plus there were over twenty independent film companies run by women. That changed when Hollywood became a profitable industry. The absence of women behind the camera affected the women who appeared in front of the lens. Because men controlled the content, they created female characters based on classic archetypes: the good girl and the fallen woman, the virgin and the whore. The women’s movement helped loosen some barriers in Hollywood. A few women, like 20th century Fox President Sherry Lansing, were able to rise to the top. Especially in television, where the financial stakes were lower and advertisers eager to court female viewers, strong female characters began to emerge. Premium cable channels like HBO and Showtime allowed edgy shows like Sex in the City and Girls , which dealt frankly with sex from a woman’s perspective, to thrive. One way women were able to gain clout was to use their stardom to become producers, like Jane Fonda, who had a breakout hit when she produced 9 to 5 . But despite the fact that 9 to 5 was a smash hit that appealed to broad audiences, it was still viewed as a “chick flick”. In Hollywood, movies like Bridesmaids and The Hunger Games , with strong female characters at their center and strong women behind the scenes, have indisputably proven that women centered content can be big at the box office. -

The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 Full Episode

The good wife season 5 episode 1 full episode Crime · Alicia works on a Death Row appeal with Will and Diane before going off to start her own The Good Wife (–). / 1 user 1 critic Season 5 | Episode 1. Previous . HD. See full technical specs». Edit. The Good Wife: Everything is Ending - on on CBS All Access. Season 5: Episode 1 - Everything is Ending Full Episodes. Blue Bloods Video - Cutting Losses (Sneak Peek 1). Undo. Get Ready To Watch Even More Young Sheldon! - Undo. How To Watch Criminal Minds. Alicia works on a Death Row appeal with Will and Diane before going off to start her own firm with Cary, but people begin to suspect something is afoot. The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 1 The Good Wife Season 5 Episode 2 The Good. Watch The Good Wife: Everything Is Ending from Season 5 at Watch The Good Wife - Season 5, Episode 1 - Everything is Ending: Alicia tries to balance one final Watch Full Episodes: The Good Wife. Watch The Good Wife S05E01 Season 5 Episode 1. Season 1. watch all episodes The Good Wife Season. The Good Wife - Season 5 The fifth season of the legal drama begins with Alicia and Episode 1: Everything is Ending Episode 2: The Bit Bucket Episode 3: A. Trailer; Episode 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17; 18; 19 . Watch The Good Wife Season 5 putlocker9 Full Episode Online. -

The Good Wife Season 1 Episod 11 Free Download Watch the Good Wife Online

the good wife season 1 episod 11 free download Watch The Good Wife Online. You have found a great place to watch The Good Wife online. TV Fanatic has many options available for your viewing pleasure so watch The Good Wife online now! On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 22, Alicia must decide what she'll do next as a verdict is reached in Peter's trial on the series finale. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 21, as the trial unfolds, new accusations come out and Alicia works furiously to keep Peter from going back to jail. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 20, everything goes wrong at a party to celebrate Howard and Jackie's upcoming wedding while Eli asks Jason to investigate Peter. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 19, Peter faces possible arrest while Alicia and Lucca fly to Toronto to represent an NSA agent detained by customs. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 18, the power struggle at Lockhart, Agos & Lee reaches a boiling point, and Marissa is used as leverage in the case against Peter. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 17, the firm defends a father of a shooting victim when he puts up a billboard calling a gun store owner a murderer. What's Diane's plan for the firm? What does the FBI have on Peter? Check out our recap and review of The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 16. On The Good Wife Season 7 Episode 15, Eli hires Elsbeth Tascioni to find out why the FBI is after Peter while Alicia joins a secret panel of attorneys on a case. -

GOOD WIFE by Robert King & Michelle King

THE GOOD WIFE by Robert King & Michelle King January 29, 2009 TEASER A VIDEO IMAGE of... ...a packed press conference. A lower-third chyron trumpets “Chicago D.A. Resigns” as the grim D.A. approaches a podium, his wife beside him. He clears his throat, reads: DAVID FOLLICK Good morning. An hour ago, I resigned as States Attorney of Cook County. I did this with a heavy heart and a deep commitment to fight these scurrilous charges. At the same time, I need time to atone for my private failings with my wife, Alicia, and our two children. Oh, one of those press conferences. Scandal. In the key of Elliott Spitzer. DAVID FOLLICK (40) is a back-slapping Bill Clinton: smart, funny, calculatedly seductive, and now at the end of his career. But he’s not our hero. Our hero is... ...his wife, ALICIA (late-30s) standing beside him. Pretty. Proper. She’s always been the good girl-- the good girl who became the good wife, then the good mom: devoted, struggling not to outshine her husband. We move in on her as we hear... DAVID FOLLICK (CONT’D) I want to be clear. I have never abused my office. I have never traded lighter sentences for either financial or sexual favors. Ugh. We suddenly enter the video, and we’re there with... Alicia as she looks out at the excited reporters, the phalanx of cameras all clicking, boring in on her. DAVID FOLLICK (CONT’D) But I do admit to a failure of judgment in my private dealings with these women.