Public Transport Accessibility & Deprivation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4203 SLT Brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1

4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1 South London Trams Transport for Everyone The case for extensions to Tramlink 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 2 South London Trams Introduction South London Partnership Given the importance of good Tramlink is a highly successful integrated transport and the public transport system. It is is the strategic proven success of Tramlink reliable, frequent and fast, offers a partnership for south in the region, South London high degree of personal security, Partnership together with the is well used and highly regarded. London. It promotes London Borough of Lambeth has the interests of south established a dedicated lobby This document sets out the case group – South London Trams – for extensions to the tram London as a sub-region to promote extensions to the network in south London. in its own right and as a Tramlink network in south London, drawing on the major contributor to the widespread public and private development of London sector support for trams and as a world class city. extensions in south London. 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 4 South London Trams Transport for Everyone No need for a ramp operated by the driver “Light rail delivers The introduction of Tramlink has The tram has also enabled Integration is key to Tramlink’s been hugely beneficial for its local previously isolated local residents success. Extending Tramlink fast, frequent and south London community. It serves to travel to jobs, training, leisure provides an opportunity for the reliable services and the whole of the community, with and cultural activities – giving wider south London community trams – unlike buses and trains – them a greater feeling of being to enjoy these benefits. -

CROSS RIVER TRAM: Linking Key Development, Transportation and Regeneration Sites Through the Historical Heart of London

CROSS RIVER TRAM: Linking key development, transportation and regeneration sites through the historical heart of London Rail~Volution Conference, Miami 2007 Ian Druce 1 London’s Cross River Tram Project London – A Quick Overview Ι Capital of England and the UK Ι Population – 8m (central), 13m (metro) Ι Strategic Planning – Mayor of London & Greater London Authority Ι Transportation Planning & Delivery – Transport for London Ι Local Administration - 33 planning authorities Ι Over 2000 years old! 2 London’s Cross River Tram Project London’s Transportation Network Ι 12 line underground ‘tube’ network dating from 1863 Ι 24-hour bus network (700+ routes) Ι Overground rail network and ‘Tramlink’ LRT Ι Ticketless smartcard system (‘Oyster’) Ι Regulated taxis and private-hire vehicles Ι 5 major airports Ι 360 mile road network & 6,000 traffic lights Ι Congestion Charging ($16/day) Ι Transit carries 10m pax/day or 3b pax/year Ι Central London mode share of 40% 3 London’s Cross River Tram Project London’s Planning and Policy Context Ι London Plan and the Mayor’s Transport Strategies set the vision and context for the planning and development of transit in the city. Ι Objectives include: ■ accommodating growth within the existing city boundaries; ■ making London a more liveable city; ■ making London a more prosperous city with the benefits shared by all; ■ promoting social inclusion and tackling deprivation and discrimination ■ improving accessibility with fast and efficient transport; and ■ making London a more attractive, well-designed and green -

Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This Page Intentionally Left Blank H6309-Prelims.Qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page Iii

H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page i Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This page intentionally left blank H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iii Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Architectural Press is an imprint of Elsevier H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2005 Editorial matter and selection Copyright © 2005, Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey. All rights reserved Individual contributions Copyright © 2005, the Contributors. All rights reserved No parts of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’. -

News from Europe News from EMTA

news July 2002 - n° 9 services have been investigated, including urban traffic control systems, News from Europe bus priority services, public transport route planning for travellers, ticket information and purchase, information on parking availability, and delays and congestion on the roads. The final report of the project can Project of new European Regulation be downloaded from the webiste. on Public Service Obligations: work is going on www.mobiservice.org.uk The project of new European Regulation on public service obligations in the field of passenger transport was not discussed at the Council of Italy boosts car-sharing Ministers of Transport in Luxembourg in June because of the opposition The Italian Ministry of the Environment launched in April a national plan of some countries. However, work is going on so as to find a compro- of promotion of car-sharing, that will receive € 9.5m of governmental mise. The draft might thus be adopted at the end of the year under grants devoted to help fund local car-sharing initiatives operated by local Danish presidency. The Danish government, that will take over from the transport authorities. Ministry officials estimate that 100,000 motorists Spanish chairmanship of the EU as of July, has expressed the wish to could take part in the new schemes by 2005, reducing CO2 emissions focus its work on increasing competition for the benefit of businesses by 20,000 tonnes and the number of cars on Italy’s roads by 50-100,000 and consumers, and to achieve liberalisation of the European railway vehicles over the period 2002-2005. -

2017 Annual Report Plc Redrow Sense of Wellbeing

Redrow plc Redrow Redrow plc Redrow House, St. David’s Park, Flintshire CH5 3RX 2017 Tel: 01244 520044 Fax: 01244 520720 ANNUAL REPORT Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 01 STRATEGIC REPORT STRATEGIC REDROW ANNUAL REPORT 2017 A Better Highlights Way to Live £1,660m £315m 70.2p £1,382m £250m 55.4p £1,150m £204m 44.5p GOVERNANCE REPORT GOVERNANCE 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 £1,660m £315m 70.2p Revenue Profit before tax Earnings per share +20% +26% +27% 17p 5,416 £1,099m 4,716 £967m STATEMENTS FINANCIAL 4,022 10p £635m 6p 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 Contents 17p 5,416 £1,099m Dividend per share Legal completions (inc. JV) Order book (inc. JV) SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION SHAREHOLDER STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SHAREHOLDER 01 Highlights 61 Corporate Governance 108 Independent Auditors’ INFORMATION +70% +15% +14% 02 Our Investment Case Report Report 148 Corporate and 04 Our Strategy 62 Board of Directors 114 Consolidated Income Shareholder Statement Information 06 Our Business Model 68 Audit Committee Report 114 Statement of 149 Five Year Summary 08 A Better Way… 72 Nomination Committee Report Comprehensive Income 16 Our Markets 74 Sustainability 115 Balance Sheets Award highlights 20 Chairman’s Statement Committee Report 116 Statement of Changes 22 Chief Executive’s 76 Directors’ Remuneration in Equity Review Report 117 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Operating Review 98 Directors’ Report 118 Accounting Policies 48 Financial Review 104 Statement of Directors’ 123 Notes to the Financial 52 Risk -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

SOC/T337/Stage2/0710 16 July 2010 Dear Stakeholder Routes 153, 299

Our Ref: SOC/T337/Stage2/0710 Consultation and Engagement Centre Surface Transport Communications Transport for London 11th Floor, Zone G2, Palestra 197 Blackfriars Road London SE1 8NJ [email protected] 16 July 2010 Dear Stakeholder Routes 153, 299, W4, W5, W6 & W10 We have now reviewed routes 153, 299, W4, W5, W6, and W10 and would like to hear your views on our proposals. Our review took account of passenger usage, reliability issues, timetables, vehicle type, area served and passenger and stakeholder feedback. As with all reviews this was done in a network context, including consideration of parallel services. We are grateful to those who have already responded with comments. These have been carefully considered and this letter includes our analysis of the main points raised. We are currently inviting tender bids from operators for routes 299, W4, W5, W6 and W10 for contracts starting in February 2011. The contract for route 153 will be extended by two years from February 2011. Route 153 (Finsbury Park Station – Liverpool Street Station) We are not proposing any permanent changes to the current structure of this route or to the frequency. From August 2010, we are proposing that buses on route 153 will be diverted to serve Chiswell Street and Finsbury Pavement in the City of London in both directions for approximately two years. New stops would be provided on Chiswell Street in both directions and on Finsbury Pavement towards Liverpool Street Station (eastbound). The diversion is required because Silk Street and Milton Street will become one way westbound in connection with the Heron Tower development meaning buses cannot serve them. -

Final Report

Existing Public Realm Strategies and Development Plans Chancery Lane 27 6. Existing Public Realm Strategies & Development Plans Public Realm Strategies regard to paving materials, street furniture, signage and street lighting. Each of the London Boroughs associated with Chancery Lane has developed a streetscape design manual which is to be used Local Development Proposals and Initiatives as guidance for enhancing the public realm throughout their respective areas. Thameslink 2000 and Crossrail: Proposals have been put forward by Thameslink 2000 for the The City of London’s Street Scene Manual which was published redevelopment of Blackfriars and Farringdon Stations, work is by the City of London in 2005 sets out the vision for the public due to start in 2007 and 2008 respectively The Thameslink 2000 realm of the City. It recognises that each street is not only a network is to provide for improved links to King’s Cross and St. route to travel along, but that it is a place where people meet Pancras, South London, and the Southeast of England, including or an important setting for historic buildings as well as brand Ashford international. Farringdon may also become a Crossrail Thameslink 2000 - Environmental Statement - June 2004 Thameslink 2000 - Environmental Statement - new architectural innovations. The aim of the manual is ‘to Farringdon - proposed Cowcross Street entrance stop that will link through to Paddington, Canary Wharf, Heathrow, create a first class public realm that is attractive, uncluttered Shenfield and eventually Maidenhead. and accessible for all’. If both schemes are realised, Farringdon might become one of The City of Westminster’s manual is the ‘Westminster Way: a the most important regional public transportation hubs in Greater public realm manual for the City’ (draft). -

DOWNLOAD London.PDF • 5 MB

GORDON HILL HIGHLANDS 3.61 BRIMSDOWN ELSTREE & BOREHAMWOOD ENFIELD CHASE ENFIELD TOWN HIGH BARNET COCKFOSTERS NEW BARNET OAKWOOD SOUTHBURY SOUTHBURY DEBDEN 9.38 GRANGE PARK PONDERS END LOUGHTON GRANGE BUSH HILL PARK COCKFOSTERS PONDERS END 6.83 4.96 3.41 OAKLEIGH PARK EAST BARNET SOUTHGATE 4.03 4.01 JUBILEE CHINGFORD WINCHMORE HILL BUSH HILL PARK 6.06 SOUTHGATE 4.24 CHINGFORD GREEN TOTTERIDGE & WHETSTONE WINCHMORE HILL BRUNSWICK 2.84 6.03 4.21 ENDLEBURY 2.89 TOTTERIDGE OAKLEIGH EDMONTON GREEN LOWER EDMONTON 3.10 4.11 3.57 STANMORE PALMERS GREEN HASELBURY SOUTHGATE GREEN 5.94 CHIGWELL WOODSIDE PARK PALMERS GREEN 5.23 EDMONTON GREEN 3.77 ARNOS GROVE 10.64 LARKSWOOD RODING VALLEY EDGWARE SILVER STREET MILL HILL BROADWAY 4.76 MONKHAMS GRANGE HILL NEW SOUTHGATE VALLEY HATCH LANE UPPER EDMONTON ANGEL ROAD 8.04 4.16 4.41 MILL WOODHOUSE COPPETTS BOWES HATCH END 5.68 9.50 HILL MILL HILL EAST WEST FINCHLEY 5.12 4.41 HIGHAMS PARK CANONS PARK 6.07 WEST WOODFORD BRIDGE FINCHLEY BOUNOS BOWES PARK 3.69 5.14 GREENBOUNDS GREEN WHITE HART LANE NORTHUMBERLAND PARK HEADSTONE LANE BURNT OAK WOODSIDE WHITE HART LANE HAINAULT 8.01 9.77 HALE END FAIRLOP 4.59 7.72 7.74 NORTHUMBERLAND PARK AND BURNT OAK FINCHLEY CENTRAL HIGHAMS PARK 5.93 ALEXANDRA WOOD GREEN CHURCH END RODING HIGHAM HILL 4.58 FINCHLEY 4.75 ALEXANDRA PALACE CHAPEL END 3.13 4.40 COLINDALE EAST 5.38 FULLWELL CHURCH 5.25 FAIRLOP FINCHLEY BRUCE 5.11 4.01 NOEL PARK BRUCE GROVE HARROW & WEALDSTONE FORTIS GREEN GROVE TOTTENHAM HALE QUEENSBURY COLINDALE 4.48 19.66 PINNER 3.61 SOUTH WOODFORD HENDON WEST -

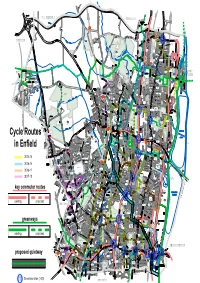

Cycle Routes in Enfield

9'.9;0*#6(+'.& $41:$1740' CREWS HILL Holmesdale Tunnel Open Space Crews Hill Whitewebbs Museum Golf Course of Transport Capel Manor Institute of Lea Valley Lea Valley Horticulture and Field Studies *'465/'4' Sports Centre High School 20 FREEZYWATER Painters Lane Whitewebbs Park Open Space Aylands Capel Manor Primary School Open Space Honilands Primary School Bulls Cross Field Whitewebbs Park Golf Course Keys Meadow School Warwick Fields Open Space Myddelton House and Gardens Elsinge St John's Jubilee C of E Primary School Freezywaters St Georges Park Aylands C of E Primary School TURKEY School ENFIELD STREET LOCK St Ignatius College RC School Forty Hall The Dell Epping Forest 0%4 ENFIELD LOCK Hadley Wood Chesterfield Soham Road Forty Hill Primary School Recreation Ground '22+0) Open Space C of E Primary School 1 Forty Hall Museum (14'56 Prince of Wales Primary School HADLEY Hadley Wood Hilly Fields Gough Park WOOD Primary School Park Hoe Lane Albany Leisure Centre Wocesters Open Space Albany Park Primary School Prince of Oasis Academy North Enfield Hadley Wales Field Recreation Ground Ansells Eastfields Lavender Green Primary School St Michaels Primary School C of E Hadley Wood Primary School Durants Golf Course School Enfield County Lower School Trent Park Country Park GORDON HILL HADLEY WOOD Russet House School St George's Platts Road Field Open Space Chase Community School St Michaels Carterhatch Green Infant and Junior School Trent Park Covert Way Mansion Queen Elizabeth David Lloyd Stadium Centre ENFIELD Field St George's C of E Primary School St James HIGHWAY St Andrew's C of E Primary School L.B. -

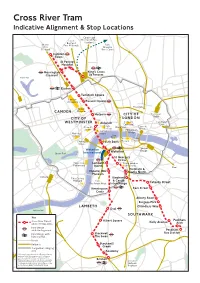

Cross River Tram Indicative Alignment & Stop Locations

Cross River Tram Indicative Alignment & Stop Locations Cambridge Luton The North East Bedford Scotland North East Midlands Paris West Brussels Scotland Kent Coast Camden Town St Pancras Hospital Mornington King's Cross Crescent St Pancras Regents Park Euston Tavistock Square London University Russell Square Moorgate British CAMDEN Museum Holborn CITY OF Liverpool Street CITY OF LONDON LSE WESTMINSTER St Paul’s Fenchurch Aldwych Cathedral Street Covent Kings Blackfriars Cannon Garden College Street Somerset Millennium National House Bridge Gallery Oxo Tower Tate Globe Charing South Bank Modern Theatre Cross Waterloo London Waterloo Bridge Green Park International St George's Circus Houses of Lambeth South London Parliament University North Kent Elephant & Imperial War Castle North Museum Victoria Tate Gallery Elephant Millbank Paris & Castle The South West Interchange Catesby Street Kennington East Street Cross Albany Road Burgess Park LAMBETH Chandlers Way Battersea Park Oval SOUTHWARK Key Peckham Cross River Transit Albert Square Kelly Avenue and potential stops Arch Interchange with Underground Peckham Interchange with Stockwell Bus Station National Rail The Swan Roads Railtrack Stockwell Green Congestion charging area Academy This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Brixton Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Croydon copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil Gatwick proceedings. (GLA) (100032379) (2004) Brighton. -

5 the MASTERPLAN 5.1 Estate Wide Vision

5 THE MASTERPLAN 5.1 Estate Wide Vision 5.1 Estate-Wide Vision 5.2 Landscape Masterplanning Principles 5.3 Intervention Area Masterplan Vision 5.4 Intervention Area Masterplan Details Hawkins\Brown © | May 2019 | 9028 | Alton Estate, Roehampton 49 5 THE MASTERPLAN 5.1 Estate-Wide Vision 5.1. 1 A New Centre The original (LCC) Alton Estate Masterplan envisaged a new civic space at the eastern end of Danebury Avenue. This would be marked by a retail parade as well as a public square. This ambition was never delivered in full. While the existing Danebury Centre provides a viable retail parade including Roehampton Library, there is no clear focal point in the form of a cohesive public space or significant . Looking further afield, while communal green space is not lacking, there is also a very limited amount of civic public space throughout Alton West, Roehampton Village and Alton East. We propose to create a new Village Square to create the focal point that these three areas are in need of. As described in more detail later in this section, the square is carefully positioned to allow each of these urban areas visibiilty, access and frontage Roehampton onto the space. The location diverges from that proposed in the Village 2014 Alton Area Masterplan, which included a square further to the west. This previous location was surrounded predominantly by new development rather than a combinaton of new and Alton West existing buildings. Critically, our new location reveals the existing - and previously hidden - St Joseph's Church along the square's eastern edge.