Finding Common Ground , File Type

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Household Income in Cardiff by Ward 2015 (CACI

HOUSEHOLD INCOME 2015 Source: Paycheck, CACI MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME IN CARDIFF BY WARD, 2015 Median Household Area Name Total Households Income Adamsdown 4,115 £20,778 Butetown 4,854 £33,706 Caerau 5,012 £20,734 Canton 6,366 £28,768 Cathays 8,252 £22,499 Creigiau/St. Fagans 2,169 £48,686 Cyncoed 4,649 £41,688 Ely 6,428 £17,951 Fairwater 5,781 £21,073 Gabalfa 2,809 £24,318 Grangetown 8,894 £23,805 Heath 5,529 £35,348 Lisvane 1,557 £52,617 Llandaff 3,756 £39,900 Llandaff North 3,698 £22,879 Llanishen 7,696 £32,850 Llanrumney 4,944 £19,134 Pentwyn 6,837 £23,551 Pentyrch 1,519 £42,973 Penylan 5,260 £38,457 Plasnewydd 7,818 £24,184 Pontprennau/Old St. Mellons 4,205 £42,781 Radyr 2,919 £47,799 Rhiwbina 5,006 £32,968 Riverside 6,226 £26,844 Rumney 3,828 £24,100 Splott 5,894 £21,596 Trowbridge 7,160 £23,464 Whitchurch & Tongwynlais 7,036 £30,995 Cardiff 150,217 £27,265 Wales 1,333,073 £24,271 Great Britain 26,612,295 £28,696 Produced by Cardiff Research Centre, The City of Cardiff Council Lisvane Creigiau/St. Fagans Radyr Pentyrch Pontprennau/Old St. Mellons Cyncoed Llandaff Penylan Heath Butetown Rhiwbina rdiff Council Llanishen Whitchurch & Tongwynlais Canton Great Britain Cardiff Riverside Gabalfa Wales Plasnewydd Rumney Grangetown Pentwyn Trowbridge Llandaff North Cathays Splott Fairwater Median Household Income (Cardiff Wards), 2015 Wards), (Cardiff Median HouseholdIncome Adamsdown Caerau Llanrumney Producedby Research TheCardiff Centre, Ca City of Ely £0 £60,000 £50,000 £40,000 £30,000 £20,000 £10,000 (£) Income Median DISTRIBUTION OF HOUSEHOLD INCOME IN CARDIFF BY WARD, 2015 £20- £40- £60- £80- Total £0-20k £100k+ Area Name 40k 60k 80k 100k Households % % % % % % Adamsdown 4,115 48.3 32.6 13.2 4.0 1.3 0.5 Butetown 4,854 29.0 29.7 20.4 10.6 5.6 4.9 Caerau 5,012 48.4 32.7 12.8 4.0 1.4 0.7 Canton 6,366 34.3 32.1 18.4 8.3 3.9 3.0 Cathays 8,252 44.5 34.2 14.2 4.6 1.6 0.8 Creigiau/St. -

City of Cardiff Council Cyngor Dinas Caerdydd

CITY OF CARDIFF COUNCIL CYNGOR DINAS CAERDYDD CABINET MEETING: 17 JULY 2014 INTRODUCTION OF AN ADDITIONAL LICENSING SCHEME IN THE PLASNEWYDD COMMUNITY WARD REPORT OF DIRECTOR OF ENVIRONMENT AGENDA ITEM:14 PORTFOLIO: ENVIRONMENT (COUNCILLOR BOB DERBYSHIRE) Reason for this Report 1. To report on the results of the consultation exercise approved by EBM on the 19th December 2012, and detail the case for declaration of an Additional Licensing Scheme in the Plasnewydd Community Ward of Cardiff in relation to houses in multiple occupation (HMOs) in the private rented sector. 2. To make Cabinet aware of progress with the Cathays Additional HMO Licensing Scheme and to seek authorisation to commence all consultation required for the redesignation of the scheme in 2015. Background 3. A motion was put to Council on 20 November 2008 highlighting the impact of a high student population in certain areas of the City. The motion called for officers to explore how the provisions of the Housing Act 2004 for extending licensing of HMOs might be applied to Cardiff. A Task & Finish group consisting of Officers and Members was established to consider options for moving forward. 4. The Group established that Additional Licensing of HMOs could provide part of an effective solution. It then considered which area would benefit most and what could be reasonably achieved within the time available. It showed that Cathays would benefit most from the introduction of a licensing scheme, although the statistics also suggested Plasnewydd and Gabalfa might merit from the extension of the licensing scheme in the future. 5. On the 4 March 2010 the Council’s Executive approved the introduction of an Additional Licensing Scheme for the Cathays Community Ward of Cardiff. -

Execbusiness9sept04 LEA Governors

CARDIFF COUNCIL CYNGOR CAERDYDD EXECUTIVE BUSINESS MEETING: 9 SEPTEMBER 2004 APPOINTMENT OF LEA SCHOOL GOVERNORS AGENDA ITEM: 2 (ii) Reason for this Report 1. To appoint LEA governors to current and impending vacancies in the context of the Council’s statutory duty. Background 2. At the Executive Business Meeting on 22 July 2004 a new process for the appointment and removal of LEA school governors was agreed. 3. The appointments are made by the Executive under section 2.2.(c).(i) of the Scheme of Delegations (30 May 2002). Issues 4. Officers have received notification from existing governors who wish to re-stand when their term of office expires and have also received applications from new applicants. The names of all eligible applicants who have met the criteria established by the Council (Minute No. Exec M/04003) are included in the Appendix for the Executive’s consideration. Reasons for Recommendations 5. The County Council has a statutory duty to appoint LEA governors. Legal Implications 6. Governor appointments are executive decisions. All decisions taken by or on behalf of the Council must (a) be within the legal powers of the Council; (b) comply with any procedural requirement imposed by law; (c) be within the powers of the body or person exercising powers on behalf of the Council; (d) be undertaken in accordance with the procedural requirements imposed by the Council, e.g. standing orders and financial regulations; (e) be fully and properly informed; (f) be properly motivated; (g) be taken having regard to the Council’s fiduciary duty to its taxpayers; and (h) be reasonable and proper in all the circumstances. -

Applications Received Week Ending 24.06.2021

CARDIFF COUNTY COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED DURING WEEK ENDING 24th JUNE 2021 The attached list shows those planning applications received by the Council during the stated week. These applications can be inspected during normal working hours at the address below: PLANNING, TRANSPORT AND ENVIRONMENT COUNTY HALL CARDIFF CF10 4UW Any enquiries or representations should be addressed to the CHIEF STRATEGIC PLANNING, HIGHWAYS, TRAFFIC & TRANSPORTATION OFFICER at the above address. In view of the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, such representations will normally be available for public inspection. Future Planning Committee Dates are as follows: 21 July 2021 18 August 2021 Total Count of Applications: 75 ADAMSDOWN 21/01563/MNR Non Material Amendment Expected Decision Level: DEL Received: 24/06/2021 Ward: ADAMSDOWN Case Officer: Mark Hancock Applicant: Mr Philip Hodge , Oak Cottage, Ty Mawr Road, Whitchurch Agents: R N Design Architectural Consultants, 4 Woolacombe Avenue, Llanrumney, Cardiff, , CF3 4TE Proposal: TO REDUCE FOOTPRINT OF GROUND FLOOR FLAT BY MOVING AWAY FROM BOUNDARY OF No. 99 AND SETBACK TO REPLICATE LAYOUT OF FIRST FLOOR FLAT - PREVIOUSLY APPROVED UNDER 18/01200/MNR At: 95-97 BROADWAY, ADAMSDOWN, CARDIFF, CF24 1QF BUTETOWN 21/01478/MNR Full Planning Permission Expected Decision Level: DEL Received: 14/06/2021 Ward: BUTETOWN Case Officer: Tracey Connelly Applicant: . DS Holdings (Cardiff Bay) Ltd, , , Agents: Asbri Planning Ltd, Unit 9 Oak Tree Court, Mulberry Drive, Cardiff Gate Business Park, Cardiff, SA1 1NW Proposal: PROPOSED GATES AND RAILINGS At: PLATFORM, HEMINGWAY ROAD, ATLANTIC WHARF, CARDIFF, CF10 5LS LBC/21/00001/MNRListed Building Consent Expected Decision Level: DEL Received: 11/06/2021 Ward: BUTETOWN Case Officer: Tracey Connelly Applicant: . -

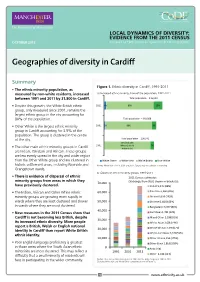

Geographies of Diversity in Cardiff

LOCAL DYNAMICS OF DIVERSITY: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2011 CENSUS OCTOBER 2013 Prepared by ESRC Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) Geographies of diversity in Cardiff Summary Figure 1. Ethnic diversity in Cardiff, 1991-2011 • The ethnic minority population, as measured by non-white residents, increased a) Increased ethnic minority share of the population, 1991-2011 between 1991 and 2011 by 31,800 in Cardiff. Total population – 346,090 • Despite this growth, the White British ethnic 2011 4% 80% 15% group, only measured since 2001, remains the largest ethnic group in the city accounting for 80% of the population. Total population – 310,088 • Other White is the largest ethnic minority 2001 2% 88% 9% group in Cardiff accounting for 3.5% of the population. The group is clustered in the centre of the city. Total population – 296,941 93% (includes 1991 White Other & 7% • The other main ethnic minority groups in Cardiff White Irish) are Indian, Pakistani and African. These groups are less evenly spread in the city and wider region than the Other White group and are clustered in White Other White Irish White British Non-White historic settlement areas, including Riverside and Notes: White Irish <1% in 2001 and 2011. Figures may not add due to rounding. Grangetown wards. b) Growth of ethnic minority groups, 1991-2011 • There is evidence of dispersal of ethnic 2011 Census estimates minority groups from areas in which they 70,000 (% change from 2001 shown in brackets): have previously clustered. Indian 9,435 (88%) • The Indian, African and Other White ethnic 60,000 Pakistani 6,960 (40%) minority groups are growing more rapidly in African 6,639 (162%) wards where they are least clustered and slower 50,000 Chinese 6,182 (105%) in wards where they are most clustered. -

Cardiff Flood Risk Management Plan Consultation Draft

Cardiff Flood Risk Management Plan Consultation Draft October 2015 Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for Cardiff Council’s information and use in relation to Cardiff Council Flood Risk Management Plan Atkins Limited assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. Document history Job number: 5138009 Document ref: 5138009/DG01 Revision Purpose description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Rev 1.0 Cardiff Council Officer KIO / LG A Cox J Jones 08/07/15 Review Rev 2.0 Consultation issue, KIO D Brain 30/09/15 combined to single document Rev 3.0 Cardiff Council Officer D Brain 05/10/15 Amendments Cardiff FRMP - v3 combined document Cardiff Flood Risk Management Plan Consultation Draft Executive Summary Flood Risk Management Plans (FRMPs) highlight the hazards and risks of flooding from rivers, the sea, surface water, groundwater and reservoirs, and set out how Risk Management Authorities (RMAs) work together with communities to manage flood risk. As a Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA) with a Flood Risk Area a statutory responsibility was placed on the City of Cardiff Council to prepare a FRMP. This FRMP has been developed with this in mind and sets out how Cardiff Council will over the next 6 years manage flooding so that the communities most at risk and the environment benefit the most. Purpose of Flood Risk Management Plans in managing flood risk Flooding remains a key threat to communities across Wales, and managing this risk through careful planning is important to minimise the risk to communities. -

Cardiff Council

LA Governor Vacancies - Recommendations from LA Governor Panel Appendix 1 1 March 2021 to 30 June 2021 i. All appointments in the list are recommended by the LA Governor Panel and will have satisfied the required application process. ii. All terms of office unless otherwise stated are for 4 years. Existing LA Governor Vacancies School Name Ward Start of Vacancy Applications Received Baden Powell Primary School Splott 30/01/2021 Cantonian High School Fairwater 05/01/2021 Cardiff West Community High School Caerau 10/12/2020 Joanne Larner Creigiau Primary School Creigiau & St Fagans 27/05/2020 Eastern High Trowbridge 09/11/2020 Jessica Morgan Hawthorn Primary School Llandaff North 26/09/2020 Millbank Primary School Caerau 11/02/2021 Peter Lea Primary School Fairwater 12/01/2021 Pontprennau Primary School Pontprennau & Old St Mellons 09/09/2019 Springwood Primary School Pentwyn 24/02/2021 Jessica Gow The Hollies School Pentwyn 28/03/2020 The Rainbow Federation Llanrumney 13/12/2021 Tremorfa Nursery School Splott 08/12/2020 Whitchurch Primary School 20/12/2020 X 2 vacancies Whitchurch & Tongwynlais 07/03/2020 Simon Morgan Windsor Clive Primary School Ely Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Bro Edern Penylan 28/11/2020 Ysgol Gymraeg Coed-Y-Gof Fairwater 29/01/2020 Ysgol Gymraeg Nant Caerau Caerau 19/11/2020 Ysgol Gymraeg Pwll Coch Canton 18/06/2020 Ysgol Y Wern Llanishen 16/11/2020 3 Future LA Governor Vacancies New Re-appointment Application School Ward Start of Vacancy Requested Received Albany Primary School Plasnewydd 19/05/2021 Cardiff High School Cyncoed -

Street Ward Postcode Construction Type Number of Properties Aberdaron Road Trowbridge CF3 1SE No Fines 7 Aberdaron Road Trowbrid

Number of Street Ward Postcode Construction Type properties Aberdaron Road Trowbridge CF3 1SE No Fines 7 Aberdaron Road Trowbridge CF3 1SF No Fines 17 Aberdaron Road Trowbridge CF3 1SG No Fines 10 Aberdovey Street Splott CF24 2ER Traditional Solid 6 Aberdulais Road Llandaff North CF14 2PH BISF 8 Aberdulais Road Llandaff North CF14 2PJ BISF 2 Abergele Road Trowbridge CF3 1RR No Fines 11 Abergele Road Trowbridge CF3 1RS No Fines 9 Aberporth Road Llandaff North CF14 2PQ BISF 9 Aberystwyth Street Splott CF24 2EW Traditional Solid 1 Aberystwyth Street Splott CF24 2EX Traditional Solid 1 Alfred Street Plasnewydd CF24 4TY Traditional Solid 1 Arlington Crescent Llanrumney CF3 4HL No Fines 6 Arlington Crescent Llanrumney CF3 4HN No Fines 6 Austen Close Llanrumney CF3 5QU Traditional Solid 4 Bacton Road Llandaff North CF14 2PN BISF 5 Beech House Whitchurch and Tongwynlais CF14 7EB Framed Construction 26 Beech House Whitchurch and Tongwynlais CF14 7ED Framed Construction 23 Beech House Whitchurch and Tongwynlais CF14 7EE Framed Construction 35 Beechley Drive Fairwater CF5 3SH No Fines 14 Beechley Drive Fairwater CF5 3SQ No Fines 8 Beechley Drive Fairwater CF5 3SR No Fines 11 Beresford Road Adamsdown CF24 1RA Traditional Solid 8 Blue House Road Llanishen CF14 5BW No Fines 7 Borth Road Trowbridge CF3 1RU No Fines 6 Brook Street Riverside CF11 6LH Traditional Solid 1 Browning Close Llanrumney CF3 5NJ No Fines 8 Brunswick Street Canton CF5 1LH Traditional Solid 1 Bryn Celyn Pentwyn CF23 7EE No Fines 31 Bryn Celyn Pentwyn CF23 7EF No Fines 11 Bryn Celyn -

Public Notice Plasnewydd 2 (English)

Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs) and the Housing Act 2004 PUBLIC NOTICE IN RESPECT OF INTRODUCTION OF AN ADDITIONAL LICENSING SCHEME IN THE PLASNEWYDD COMMUNITY WARD OF CARDIFF Notice Notice is hereby given that the City of Cardiff Council has confirmed the designation of an additional licensing scheme in respect of houses in multiple occupation covering the Plasnewydd Community Ward. This scheme will be known as (The City of Cardiff Council’s Houses in Multiple Occupation Additional Licensing Scheme 2020) (“The Scheme”). The confirmation of the designation is in accordance with Sections 56 to 60 of the Housing Act 2004 (“the Act”) and regulation 9 of the Licensing and Management of Houses in Multiple Occupation and Other Houses (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Wales) Regulations 2006. The designation was made at the Council’s Cabinet Meeting on 17th September 2020. The Housing Act 2004 (Additional HMO Licensing) (Wales) General Approval 2007, which came into force on 13th March 2007 applies to this designation. The Scheme will be effective from 1st January 2021 and unless revoked beforehand will cease to have effect on 1st January 2026. The Scheme applies to all Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs) within the area described above except those exempted by the relevant sections of the Act. Any landlord, person managing, or tenant within the City should seek advice from the City of Cardiff Council’s Housing Enforcement Service regarding whether a property is affected by the Plasnewydd Community Ward Additional Licensing Scheme. A person having control or managing an HMO in the designated area must apply to the City of Cardiff Council for a licence. -

Ardaloedd Chwaraeon Caerdydd Yn Agor O 3 Awst 2020 Cardiff Play Areas Open from 3 August 2020 1 Adamsdown Square Adamsdown 1

Ardaloedd chwaraeon Caerdydd yn agor o 3 Awst 2020 Cardiff play areas open from 3 August 2020 1 Adamsdown Square Adamsdown 1 Adamsdown Square Adamsdown 2 Gofod agored Adamscroft Adamsdown 2 Adamscroft Open space Adamsdown 3 Belmont Walk Butetown 3 Belmont Walk Butetown 4 Parc Britannia Butetown 4 Britannia Park Butetown 5 Parc Hamadryad Butetown 5 Hamadryad Park Butetown 6 Craiglee Drive Butetown 6 Craiglee Drive Butetown 7 Hodges Square Butetown 7 Hodges Square Butetown 8 Loudon Square Butetown 8 Loudon Square Butetown 9 Windsor Esplanade Butetown 9 Windsor esplanade Butetown 10 Emblem Close Caerau 10 Emblem Close Caerau 11 Emerson Close Caerau 11 Emerson Close Caerau 12 Heol Homfrey Caerau 12 Heol Homfrey Caerau 13 Parc Trelái Caerau 13 Trelai Park Caerau 14 Gerddi Cogan Cathays 14 Jubilee Park Canton 15 Parc Maendy Cathays 15 Sanatorium Road (Toddler) Canton 16 Parc Bute Cathays 16 Bute Park Cathays 17 Rhydlafar Creigiau a Sain Ffagan 17 Cogan Gardens Cathays 18 Maitland Park ardal ymarferion ystwytho Gabalfa 18 Maindy Park Cathays 19 Parc Maitland Gabalfa 19 Rhydlafar Creigiau / St Fagans 20 Gerddi Despenser (Plant bach) Glan-yr-afon 20 Green Farm Road Ely 21 Gerddi Despenser (Plant Iau) Glan-yr-afon 21 Wilson Road (Toddler) Ely 22 Wyndham Street Glan-yr-afon 22 Wilson Road (Junior) Ely 23 Parc 'y Tan' / Sevenoaks Grangetown 23 Beechley Road Fairwater 24 Y Marl (Plant bach) Grangetown 24 Chorley Close Fairwater 25 Y Marl (Plant Iau) Grangetown 25 Whitland Crescent Fairwater 26 Bryn Glas (Plant bach) Llanishen 26 Maitland Park agility -

Boundary Commission for Wales

Boundary Commission for Wales 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies Report on the 2018 Review of Parliamentary Constituencies in Wales BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REPORT ON THE 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN WALES Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 3 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended © Crown copyright 2018 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at Boundary Commission for Wales Hastings House Cardiff CF24 0BL Telephone: +44 (0) 2920 464 819 Fax: +44 (0) 2920 464 823 Website: www.bcomm-wales.gov.uk Email: [email protected] The Commission welcomes correspondence and telephone calls in Welsh or English. ISBN 978-1-5286-0337-9 CCS0418463696 09/18 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REPORT ON THE 2018 REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES IN WALES SEPTEMBER 2018 Submitted to the Minister for the Cabinet Office pursuant to Section 3 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended Foreword Dear Minister I write on behalf of the Boundary Commission for Wales to submit its report pursuant to section 3 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, as amended. -

DEL-Decided Lst May03

Applications Decided by Delegated Powers May 2003 AppNum Registered Applicant Location Proposal Dcn DcnDate A 03/00030/C 05/03/2003 Babak Arabestani Unit 10, 24, Mermaid Quay, ERECTION OF SIGNS TO RESTAURANT PER 14/05/2003 Butetown, Cardiff A 03/00032/C 03/03/2003 Noble House Ltd 26 Mermaid Quay, Butetown, NEW BREWERY SIGNAGE PER 28/05/2003 Cardiff A 03/00039/C 18/03/2003 Brook Street plc 20 High Street, Cathays, Cardiff DISPLAY THREE SIGNS PER 13/05/2003 A 03/00042/C 24/03/2003 PDSA 238 Bute Street, Butetown, ERECTION OF AN INTERNALLY ILLUMINATED TOTEM PER 28/05/2003 Cardiff SIGN A 03/00044/C 24/03/2003 Mc Donalds Restaurants 12-14, Queen Street, Cathays, TWO INTERNALLY ILLUMINATED FASCIA SIGNS AND PER 06/05/2003 Cardiff ONE PROJECTING SIGN A 03/00051/C 03/04/2003 Lloyds TSB Bank plc 31 Queen Street, Cathays, 2 X INTERNALLY ILLUMINATED ATM COLLAR SIZED TO PER 14/05/2003 Cardiff MATCH EXISTING NON-ILLUMINATED ATM A 03/00052/C 04/04/2003 HMV UK Ltd 51 Queen Street, Cathays, 1 NO. 3MM ALUMINIUM FASCIA FRET CUT TO ALLOW PER 14/05/2003 Cardiff LETTERS + LOGO AND 1 NO. DOUBLE SIDED PROJECTION SIGN A 03/00053/C 03/04/2003 Michael Johnson 64 Cathays Terrace, Cathays, OBTAINING PERMISSION FOR EXISTING SIGN ON REF 14/05/2003 Cardiff FRONT OF SHOP - SIGN WAS PUT UP IN 1982 A 03/00056/C 08/04/2003 Catering Horizons 103 Cathays Terrace, Cathays, RETAIN SIGNAGE SPL 28/05/2003 Contracts Ltd Cardiff 03/00391/C 20/02/2003 Cardiff University Bute Building, King Edward VII WEATHERCLAD EXTERNAL WALLS TO PREVENT PER 07/05/2003 Avenue, Cathays, Cardiff INGRESS OF WATER 03/00575/C 25/03/2003 Mr & Mrs J Dando 1 Donald Street, Plasnewydd, CONVERSION OF SHOP UNIT FOR RESIDENTIAL PER 06/05/2003 Cardiff PURPOSES (EXISTING DWELLING) AND SINGLE STOREY 03/00582/C 18/03/2003 Izakaya Japanese Tavern 1-4, St.