Additions to the Description of Paroplocephalus Atriceps (Serpentes: Elapidae) with a Discussion on Pupil Shape in It and Other Australian Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report

Geography Monograph Series No. 13 Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. Brisbane, 2009 The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. is a non-profit organization that promotes the study of Geography within educational, scientific, professional, commercial and broader general communities. Since its establishment in 1885, the Society has taken the lead in geo- graphical education, exploration and research in Queensland. Published by: The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. 237 Milton Road, Milton QLD 4064, Australia Phone: (07) 3368 2066; Fax: (07) 33671011 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rgsq.org.au ISBN 978 0 949286 16 8 ISSN 1037 7158 © 2009 Desktop Publishing: Kevin Long, Page People Pty Ltd (www.pagepeople.com.au) Printing: Snap Printing Milton (www.milton.snapprinting.com.au) Cover: Pemberton Design (www.pembertondesign.com.au) Cover photo: Cravens Peak. Photographer: Nick Rains 2007 State map and Topographic Map provided by: Richard MacNeill, Spatial Information Coordinator, Bush Heritage Australia (www.bushheritage.org.au) Other Titles in the Geography Monograph Series: No 1. Technology Education and Geography in Australia Higher Education No 2. Geography in Society: a Case for Geography in Australian Society No 3. Cape York Peninsula Scientific Study Report No 4. Musselbrook Reserve Scientific Study Report No 5. A Continent for a Nation; and, Dividing Societies No 6. Herald Cays Scientific Study Report No 7. Braving the Bull of Heaven; and, Societal Benefits from Seasonal Climate Forecasting No 8. Antarctica: a Conducted Tour from Ancient to Modern; and, Undara: the Longest Known Young Lava Flow No 9. White Mountains Scientific Study Report No 10. -

Guidelines for Keeping Venomous Snakes in the NT

GUIDELINES FOR KEEPING VENOMOUS SNAKES IN THE NT Venomous snakes are potentially dangerous to humans, and for this reason extreme caution must be exercised when keeping or handling them in captivity. Prospective venomous snake owners should be well informed about the needs and requirements for keeping these animals in captivity. Permits The keeping of protected wildlife in the Northern Territory is regulated by a permit system under the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2006 (TPWC Act). Conditions are included on permits, and the Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (“PWCNT”) may issue infringement notices or cancel permits if conditions are breached. A Permit to Keep Protected Wildlife enables people to legally possess native vertebrate animals in captivity in the Northern Territory. The permit system assists the PWCNT to monitor wildlife kept in captivity and to detect any illegal activities associated with the keeping of, and trade in, native wildlife. Venomous snakes are protected throughout the Northern Territory and may not be removed from the wild without the appropriate licences and permits. People are required to hold a Keep Permit (Category 1–3) to legally keep venomous snakes in the Northern Territory. Premises will be inspected by PWCNT staff to evaluate their suitability prior to any Keep Permit (Category 1– 3) being granted. Approvals may also be required from local councils, the Northern Territory Planning Authority, and the Department of Health and Community Services. Consignment of venomous snakes between the Northern Territory and other States and Territories can only be undertaken with an appropriate import / export permit. There are three categories of venomous snake permitted to be kept in captivity in the Northern Territory: Keep Permit (Category 1) – Mildly Dangerous Venomous Keep Permit (Category 2) – Dangerous Venomous Keep Permit (Category 3) – Highly Dangerous Venomous Venomous snakes must be obtained from a legal source (i.e. -

Different Environmental Gradients Affect Different Measures of Snake Β-Diversity in the Amazon Rainforests

Different environmental gradients affect different measures of snake β-diversity in the Amazon rainforests Rafael de Fraga1,2,3, Miquéias Ferrão1, Adam J. Stow2, William E. Magnusson4 and Albertina P. Lima4 1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia 3 Programa de Pós-graduação em Sociedade, Natureza e Desenvolvimento, Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará, Santarém, Pará, Brazil 4 Coordenação de Biodiversidade, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil ABSTRACT Mechanisms generating and maintaining biodiversity at regional scales may be evaluated by quantifying β-diversity along environmental gradients. Differences in assemblages result in biotic complementarities and redundancies among sites, which may be quantified through multi-dimensional approaches incorporating taxonomic β-diversity (TBD), functional β-diversity (FBD) and phylogenetic β-diversity (PBD). Here we test the hypothesis that snake TBD, FBD and PBD are influenced by environmental gradients, independently of geographic distance. The gradients tested are expected to affect snake assemblages indirectly, such as clay content in the soil determining primary production and height above the nearest drainage determining prey availability, or directly, such as percentage of tree cover determining availability of resting and nesting sites, and climate (temperature and precipitation) causing physiological filtering. We sampled snakes in 21 sampling plots, each covering five km2, distributed over 880 km in the central-southern Amazon Basin. We used dissimilarities between sampling sites to quantify TBD, FBD and PBD, Submitted 30 April 2018 which were response variables in multiple-linear-regression and redundancy analysis Accepted 23 August 2018 Published 24 September 2018 models. -

Raymond T. Hoser

32 Australasian Journal of Herpetology Australasian Journal of herpetology 11:32-50. Published 8 April 2012. ISSN 1836-5698 (Print) ISSN 1836-5779 (Online) THE DESCRIPTION OF A NEW GENUS OF WEST AUSTRALIAN SNAKE AND EIGHT NEW TAXA IN THE GENERA PSEUDONAJA GUNTHER, 1858, OXYURANUS KINGHORN, 1923 AND PANACEDECHIS WELLS AND WELLINGTON, 1985 (SERPENTES: ELAPIDAE) RAYMOND T. HOSER 488 Park Road, Park Orchards, Victoria, 3134, Australia. Phone: +61 3 9812 3322 Fax: 9812 3355 E-mail: [email protected] Submitted 20 March 2012, Accepted 30 March 2012, Published 8 April 2012. ABSTRACT This paper defines and names new taxa from Australasia. The taxon Denisonia fasciata Rosen 1905, placed most recently by most authors in the genus Suta, is formally removed from that genus and placed in a monotypic genus formally named and described herein. Other taxa formally named and described for the first time include subspecies of the following; the broadly recognized species Pseudonaja textilis (known as the Eastern Brown Snake), P. guttata (Speckled Brown Snake) and P. affinis (Dugite), Oxyuranus scutellatus (Taipan) from Irian Jaya and western Papua as well as a second subspecies from north-west Australia and a hitherto unnamed subspecies of Panacedechis papuanus (Papuan Blacksnake) from the same general region. The newly named taxa are: Hulimkai gen. nov., Pseudonaja textilis cliveevatti subsp. nov., Pseudonaja textilis leswilliamsi subsp. nov., Pseudonaja textilis rollinsoni subsp. nov., Pseudonaja textilis jackyhoserae subsp. nov., Pseudonaja guttata -

Broad-Headed Snake (Hoplocephalus Bungaroides)', Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales (1946-7), Pp

Husbandry Guidelines Broad-Headed Snake Hoplocephalus bungaroides Compiler – Charles Morris Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Captive Animals Certificate III RUV3020R Lecturers: Graeme Phipps, Jacki Salkeld & Brad Walker 2009 1 Occupational Health and Safety WARNING This Snake is DANGEROUSLY VENOMOUS CAPABLE OF INFLICTING A POTENTIALLY FATAL BITE ALWAYS HAVE A COMPRESSION BANDAGE WITHIN REACH SNAKE BITE TREATMENT: Do NOT wash the wound. Do NOT cut the wound, apply substances to the wound or use a tourniquet. Do NOT remove jeans or shirt as any movement will assist the venom to enter the blood stream. KEEP THE VICTIM STILL. 1. Apply a broad pressure bandage over the bite site as soon as possible. 2. Keep the limb still. The bandage should be as tight as you would bind a sprained ankle. 3. Extend the bandage down to the fingers or toes then up the leg as high as possible. (For a bite on the hand or forearm bind up to the elbow). 4. Apply a splint if possible, to immobilise the limb. 5. Bind it firmly to as much of the limb as possible. (Use a sling for an arm injury). Bring transport to the victim where possible or carry them to transportation. Transport the victim to the nearest hospital. Please Print this page off and put it up on the wall in your snake room. 2 There is some serious occupational health risks involved in keeping venomous snakes. All risk can be eliminated if kept clean and in the correct lockable enclosures with only the risk of handling left in play. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys

Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Steven P. Krichbaum May 2018 © 2018 Steven P. Krichbaum. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians by STEVEN P. KRICHBAUM has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Willem Roosenburg Professor of Biological Sciences Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract KRICHBAUM, STEVEN P., Ph.D., May 2018, Biological Sciences Ecology and Conservation Biology of the North American Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) in the Central Appalachians Director of Dissertation: Willem Roosenburg My study presents information on summer use of terrestrial habitat by IUCN “endangered” North American Wood Turtles (Glyptemys insculpta), sampled over four years at two forested montane sites on the southern periphery of the species’ range in the central Appalachians of Virginia (VA) and West Virginia (WV) USA. The two sites differ in topography, stream size, elevation, and forest composition and structure. I obtained location points for individual turtles during the summer, the period of their most extensive terrestrial roaming. Structural, compositional, and topographical habitat features were measured, counted, or characterized on the ground (e.g., number of canopy trees and identification of herbaceous taxa present) at Wood Turtle locations as well as at paired random points located 23-300m away from each particular turtle location. -

Habitat Types

Habitat Types The following section features ten predominant habitat types on the West Coast of the Eyre Peninsula, South Australia. It provides a description of each habitat type and the native plant and fauna species that commonly occur there. The fauna species lists in this section are not limited to the species included in this publication and include other coastal fauna species. Fauna species included in this publication are printed in bold. Information is also provided on specific threats and reference sites for each habitat type. The habitat types presented are generally either characteristic of high-energy exposed coastline or low-energy sheltered coastline. Open sandy beaches, non-vegetated dunefields, coastal cliffs and cliff tops are all typically found along high energy, exposed coastline, while mangroves, sand flats and saltmarsh/samphire are characteristic of low energy, sheltered coastline. Habitat Types Coastal Dune Shrublands NATURAL DISTRIBUTION shrublands of larger vegetation occur on more stable dunes and Found throughout the coastal environment, from low beachfront cliff-top dunes with deep stable sand. Most large dune shrublands locations to elevated clifftops, wherever sand can accumulate. will be composed of a mosaic of transitional vegetation patches ranging from bare sand to dense shrub cover. DESCRIPTION This habitat type is associated with sandy coastal dunes occurring The understory generally consists of moderate to high diversity of along exposed and sometimes more sheltered coastline. Dunes are low shrubs, sedges and groundcovers. Understory diversity is often created by the deposition of dry sand particles from the beach by driven by the position and aspect of the dune slope. -

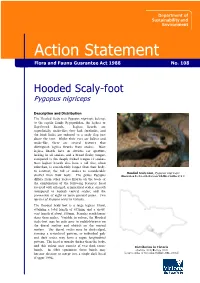

Action Statement Floraflora and and Fauna Fauna Guarantee Guarantee Act Act 1988 1988 No

Action Statement FloraFlora and and Fauna Fauna Guarantee Guarantee Act Act 1988 1988 No. No. ### 108 Hooded Scaly-foot Pygopus nigriceps Description and Distribution The Hooded Scaly-foot Pygopus nigriceps belongs to the reptile family Pygopodidae, the legless or flap-footed lizards. Legless lizards are superficially snake-like; they lack forelimbs, and the hind limbs are reduced to a scaly flap just above the vent. Whilst their eyes are lidless and snake-like, there are several features that distinguish legless lizards from snakes. Most legless lizards have an obvious ear aperture, lacking in all snakes, and a broad fleshy tongue, compared to the deeply forked tongue of snakes. Most legless lizards also have a tail that, when unbroken, is considerably longer than their body. In contrast, the tail of snakes is considerably Hooded Scaly-foot, Pygopus nigriceps shorter than their body. The genus Pygopus Illustration by Peter Robertson Wildlife Profiles P/L © differs from other legless lizards on the basis of the combination of the following features: head covered with enlarged, symmetrical scales; smooth (compared to keeled) ventral scales; and the possession of eight or more preanal pores. Two species of Pygopus occur in Victoria. The Hooded Scaly-foot is a large legless lizard, attaining a total length of 475mm, and a snout- vent length of about 180mm. Females reach larger sizes than males. Variable in colour, the Hooded Scaly-foot may be pale grey to reddish-brown on the dorsal surface and whitish on the ventral surface. The dorsal scales may be dark-edged, forming a reticulated pattern, or individual pale and dark scales may form a vague longitudinal pattern. -

An Investigation of the Evolution of Australian Elapid Snake Venoms

toxins Article Rapid Radiations and the Race to Redundancy: An Investigation of the Evolution of Australian Elapid Snake Venoms Timothy N. W. Jackson 1, Ivan Koludarov 1, Syed A. Ali 1,2, James Dobson 1, Christina N. Zdenek 1, Daniel Dashevsky 1, Bianca op den Brouw 1, Paul P. Masci 3, Amanda Nouwens 4, Peter Josh 4, Jonathan Goldenberg 1, Vittoria Cipriani 1, Chris Hay 1, Iwan Hendrikx 1, Nathan Dunstan 5, Luke Allen 5 and Bryan G. Fry 1,* 1 Venom Evolution Lab, School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (T.N.W.J.); [email protected] (I.K.); [email protected] (S.A.A.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (C.N.Z.); [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (B.o.d.B.); [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (I.H.) 2 HEJ Research Institute of Chemistry, International Centre for Chemical and Biological Sciences (ICCBS), University of Karachi, Karachi 75270, Pakistan 3 Princess Alexandra Hospital, Translational Research Institute, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] 4 School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia; [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (P.J.) 5 Venom Supplies, Tanunda, South Australia 5352, Australia; [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (L.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-4-0019-3182 Academic Editor: Nicholas R. -

Frogs & Reptiles NE Vic 2018 Online

Reptiles and Frogs of North East Victoria An Identication and Conservation Guide Victorian Conservation Status (DELWP Advisory List) cr critically endangered en endangered Reptiles & Frogs vu vulnerable nt near threatened dd data deficient L Listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (FFG, 1988) Size: of North East Victoria Lizards, Dragons & Skinks: Snout-vent length (cm) Snakes, Goannas: Total length (cm) An Identification and Conservation Guide Lowland Copperhead Highland Copperhead Carpet Python Gray's Blind Snake Nobbi Dragon Bearded Dragon Ragged Snake-eyed Skink Large Striped Skink Frogs: Snout-vent length male - M (mm) Snout-vent length female - F (mm) Austrelaps superbus 170 (NC) Austrelaps ramsayi 115 (PR) Morelia spilota metcalfei – en L 240 (DM) Ramphotyphlops nigrescens 38 (PR) Diporiphora nobbi 8.4 (PR) Pogona barbata – vu 25 (DM) Cryptoblepharus pannosus Snout-Vent 3.5 (DM) Ctenotus robustus Snout-Vent 12 (DM) Guide to symbols Venomous Lifeform F Fossorial (burrows underground) T Terrestrial Reptiles & Frogs SA Semi Arboreal R Rock-dwelling Habitat Type Alpine Bog Montane Forests Alpine Grassland/Woodland Lowland Grassland/Woodland White-lipped Snake Tiger Snake Woodland Blind Snake Olive Legless Lizard Mountain Dragon Marbled Gecko Copper-tailed Skink Alpine She-oak Skink Drysdalia coronoides 40 (PR) Notechis scutatus 200 (NC) Ramphotyphlops proximus – nt 50 (DM) Delma inornata 13 (DM) Rankinia diemensis Snout-Vent 7.5 (NC) Christinus marmoratus Snout-Vent 7 (PR) Ctenotus taeniolatus Snout-Vent 8 (DM) Cyclodomorphus praealtus -

Brigalow Belt Bioregion – a Biodiversity Jewel

Brigalow Belt bioregion – a biodiversity jewel Brigalow habitat © Craig Eddie What is brigalow? including eucalypt and cypress pine forests and The term ‘brigalow’ is used simultaneously to refer to; woodlands, grasslands and other Acacia dominated the tree Acacia harpophylla; an ecological community ecosystems. dominated by this tree and often found in conjunction with other species such as belah, wilga and false Along the eastern boundary of the Brigalow Belt are sandalwood; and a broader region where this species scattered patches of semi-evergreen vine thickets with and ecological community are present. bright green canopy species that are highly visible among the more silvery brigalow communities. These The Brigalow Belt bioregion patches are a dry adapted form of rainforest, relics of a much wetter past. The Brigalow Belt bioregion is a large and complex area covering 36,400 000ha. The region is thus recognised What are the issues? by the Australian Government as a biodiversity hotspot. Nature conservation in the region has received increasing attention because of the rapid and extensive This hotspot contains some of the most threatened loss of habitat that has occurred. Since World War wildlife in the world, including populations of the II the Brigalow Belt bioregion has become a major endangered bridled nail-tail wallaby and the only agricultural and pastoral area. Broad-scale clearing for remaining wild population of the endangered northern agriculture and unsustainable grazing has fragmented hairy-nosed wombat. The area contains important the original vegetation in the past, particularly on habitat for rare and threatened species including the, lowland areas. glossy black-cockatoo, bulloak jewel butterfl y, brigalow scaly-foot, red goshawk, little pied bat, golden-tailed geckos and threatened community of semi evergreen Biodiversity hotspots are areas that support vine thickets.