UNDERSTANDING the LITURGY Father Athanasius Iskander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nicene Creed

THE NICENE CREED A MANUAL jfor tbe use of ~anlJilJates for }ilol!} ®tlJets BY J. J. LIAS, M.A. RECTOR OF EAST BERGHOLT, COLCHESTER ; CHANCELLOR OF LLANDAFF CATHEDRAL, AND EXAMINING CHAPLAIN TO THE BISHOP OF LLANDAFF; AUTHOR OF ''PRINCIPLES OF BIBLICAL CRITICISM," ''THE ATONEMENT," ETC, LONDON SW AN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., LIM. NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO. 1897 tto SIR GEORGE STOKES, BART., LL.D., D.Sc., F.R.S. LUCASIAN PROFESSOR OF MATHEMATICS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE THIS LITTLE BOOK IS DEDICATED WITH A FEELING OF ADMIRATION FOR HIS GREAT ATTAINMENTS AND OF RESPECT FOR HIS HIGH CHARACTER AND GENUINE AND ENLIGHTENED ATTACHMENT TO THE FIRST PRINCIPLES OF ttbe lE>octrtne of <Ibtlst PREFACE T is, perhaps, necessary that I should explain my reasons I for adding one more to the vast number of books which pour forth in so continuous a stream in the present day. Four reasons have mainly weighed with me. The first is, that my experience as an examiner of candidates for Holy Orders has convinced me that many of them obtain their knowledge of the first principles of the religion which they propose to teach, in a very unsatisfactory and haphazard way. This is partly due to the absence, at least until lately, of satisfactory text books. Few candidates attempt to read Pearson's great standard work on the subject, and most of those who have attempted it find him very abstruse and difficult to follow. Moreover, it must be admitted that in a good many respects, in spite of the still inestimable value of the work, Pearson's manner and matter are out of date. -

Divine Liturgy

THE DIVINE LITURGY OF OUR FATHER AMONG THE SAINTS JOHN CHRYSOSTOM H QEIA LEITOURGIA TOU EN AGIOIS PATROS HMWN IWANNOU TOU CRUSOSTOMOU St Andrew’s Orthodox Press SYDNEY 2005 First published 1996 by Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia 242 Cleveland Street Redfern NSW 2016 Australia Reprinted with revisions and additions 1999 Reprinted with further revisions and additions 2005 Reprinted 2011 Copyright © 1996 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data The divine liturgy of our father among the saints John Chrysostom = I theia leitourgia tou en agiois patros imon Ioannou tou Chrysostomou. ISBN 0 646 44791 2. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church. Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. 2. Orthodox Eastern Church. Prayer-books and devotions. 3. Prayers. I. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia. 242.8019 Typeset in 11/12 point Garamond and 10/11 point SymbolGreek II (Linguist’s Software) CONTENTS Preface vii The Divine Liturgy 1 ïH Qeiva Leitourgiva Conclusion of Orthros 115 Tevlo" tou' ÒOrqrou Dismissal Hymns of the Resurrection 121 ÆApolutivkia ÆAnastavsima Dismissal Hymns of the Major Feasts 127 ÆApolutivkia tou' Dwdekaovrtou Other Hymns 137 Diavforoi ÓUmnoi Preparation for Holy Communion 141 Eujcai; pro; th'" Qeiva" Koinwniva" Thanksgiving after Holy Communion 151 Eujcaristiva meta; th;n Qeivan Koinwnivan Blessing of Loaves 165 ÆAkolouqiva th'" ÆArtoklasiva" Memorial Service 177 ÆAkolouqiva ejpi; Mnhmosuvnw/ v PREFACE The Divine Liturgy in English translation is published with the blessing of His Eminence Archbishop Stylianos of Australia. -

Annual Palm Sunday Seafood Dinner 6:30 P.M

Saint John the Baptist Orthodox Church, Rochester NY Great Lent, Holy Week, PASCHA: 2017 Schedule of Services First Week of Great Lent: Orthodoxy 27 February (Monday) 6:30 p.m. Compline & Canon of St. Andrew of Crete 28 February (Tuesday) 6:30 p.m. Compline & Canon of St. Andrew of Crete 1 March (Wednesday) 7:15 a.m. Daily Lenten Matins 6:30 p.m. Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts 2 March (Thursday) 6:30 p.m. Compline & Canon of St. Andrew of Crete 3 March (Friday) 12:15 p.m. Akathist: To the Divine Passion of Christ 5:15 p.m. Akathist: In Preparation for Holy Communion 4 March (Saturday) 5:00 p.m. Great Vespers; General Confession 5 March (Sunday) 10:00 a.m. Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great 5:00 p.m. Sunday of Orthodoxy Vespers ~ Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church Second Week of Great Lent: Saint Gregory Palamas 8 March (Wednesday) 7:15 a.m. Daily Lenten Matins 6:30 p.m. Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts 10 March (Friday) 12:15 p.m. Akathist: In Preparation for Holy Communion 5:15 p.m. Akathist: To the Divine Passion of Christ 11 March (Saturday) 4:30 p.m. Panikheda (memorial) for the departed 5:00 p.m. Great Vespers; individual confessions 12 March (Sunday) 10:00 a.m. Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great Third Week of Great Lent: The Veneration of the Cross 15 March (Wednesday) 7:15 a.m. Daily Lenten Matins 6:30 p.m. Liturgy of the Pre-Sanctified Gifts 17 March (Friday) 12:15 p.m. -

The Office of Vespers

THE PATRIARCHAL ORTHODOX CHURCH OF ROMANIA ARCHDIOCESE OF WESTERN EUROPE THE OFFICE OF VESPERS TYPIKON ( With Litiya & Artoklasia Service ) ? The priest vests with the epitrachelion in the sanctuary. He opens the curtain and the Royal Doors Standing before the holy table facing East, he blesses himself saying loudly : Priest Blessed is Our God, always, Now and Forever, and to the Ages of Ages. + Choir Amen. Glory to Thee our God, Glory to Thee. The Choir Leader begins the Trisagion Prayers. The priest closes the Holy Doors and curtain Choir Come let us worship and bow down before God our King ( + metanie ) Come let us worship and bow down before Christ, our King and God ( + metanie ) Come let us worship and bow down before Christ himself, our King, and our God ( + metanie ) O Heavenly King, the Paraclete, the Spirit of Truth, who are present everywhere filling all things, Treasury of good things, and Giver of Life, come and dwell in us, cleanse us of every stain, and save our souls, O Good One. + Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, Have mercy on us ( three times) + Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit, Now, and forever, and to the Ages of Ages, Amen. All Holy Trinity have mercy on us. Lord forgive us our sins. Master pardon our transgressions. Holy One, visit and heal our infirmities for your name’s sake. Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy. + Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit Now, and forever, and to the Ages of Ages, Amen. -

Divine Liturgy

THE SIGNIFICANCE AND MEANING OF THE LITURGY FOR OUR DAILY LIVES Philip Kariatlis For many Orthodox Christians today, the divine Liturgy is simply another service that they attend in order to fulfil their Christian duty - it is the proper thing to do - without it necessarily having any particular meaning for their everyday life. It is not something that they long to go to because of a real sense of personal joy that it gives to their life empowering them to face the daily challenges that they might encounter. Unfortunately, for many of our faithful - even though they are well- intentioned - in their most honest moments, the Liturgy has become a ‘joyless celebration’. It is often said, for example: “I don’t get anything out of the Service” and for this reason they feel a sense of frustration. Still others, will argue: “I consider myself a Christian but I don’t see why I need to go to Church every Sunday, if at all.” In all this, there is a real sense that, over time, our faithful have forgotten not only what the Liturgy is essentially all about, but equally importantly the significance of this celebration for their everyday life. Even the phrase that is often used, “I attend the Liturgy” shows that over time it has become misunderstood. Far from the Liturgy being a theatrical performance between priest and chanters at which the faithful are simply present, from the very beginning, even in its most primitive form as can be witnessed in the New Testament, the Eucharist was something that the faithful actively participated in, and not simply passively attended, an event that was personally enriching and powerfully transformative for their life. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

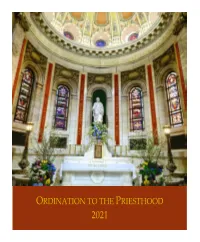

ORDINATION 2021.Pdf

WELCOME TO THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL Restrooms are located near the Chapel of Saint Joseph, and on the Lower Level, which is acces- sible via the stairs and elevator at either end of the Narthex. The Mother Church for the 800,000 Roman Catholics of the Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, the Cathedral of Saint Paul is an active parish family of nearly 1,000 households and was designated as a National Shrine in 2009. For more information about the Cathedral, visit the website at www.cathedralsaintpaul.org ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS SAINT PAUL, MINNESOTA Cover photo by Greg Povolny: Chapel of Saint Joseph, Cathedral of Saint Paul 2 Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis Ordination to the Priesthood of Our Lord Jesus Christ E Joseph Timothy Barron, PES James Andrew Bernard William Duane Duffert Brian Kenneth Fischer David Leo Hottinger, PES Michael Fredrik Reinhardt Josh Jacob Salonek S May 29, 2021 ten o’clock We invite your prayerful silence in preparation for Mass. ORGAN PRELUDE Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ Vêpres du commun des fêtes de la Sainte Vierge, op. 18 Marcel Dupré Ave Maris Stella I. Sumens illud Ave Gabrielis ore op. 18, No. 6 II. Monstra te esse matrem: sumat per te preces op. 18, No. 7 III. Vitam praesta puram, iter para tutum: op. 18, No. 8 IV. Amen op. 18, No. 9 3 HOLY MASS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Celebrant THE INTRODUCTORY RITES INTROITS Sung as needed ALL PLEASE STAND Priests of God, Bless the Lord Peter Latona Winner, Rite of Ordination Propers Composition Competition, sponsored by the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians (2016) ANTIPHON Cantor, then Assembly; thereafter, Assembly Verses Daniel 3:57-74, 87 1. -

Mass of Ordination to the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020

Mass of Ordination To the Holy Priesthood June 27, 2020 Prayer for the Holy Father O God who in your providential design willed that your Church be built upon blessed Peter, whom you set over the other Apostles, look with favor, we pray, on Francis our Pope and grant that he, whom you have made Peter’s successor, may be for your people a visible source and foundation of unity in faith and of communion. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English Translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved. Most Reverend Michael R. Cote, D.D. Bishop of Norwich Prayer for the Bishop O God, eternal shepherd of the faithful, who tend your Church in countless ways and rule over her in love, grant, we pray, that Michael, your servant, whom you have set over your people, may preside in the place of Christ over the flock whose shepherd he is, and be faithful as a teacher of doctrine, a Priest of sacred worship and as one who serves them by governing. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Excerpt from the English translation of the Roman Missal ©2011, ICEL, All rights reserved 1 CELEBRATION OF THE ORDINATION TO THE PRIESTHOOD OF Reverend Michael Patrick Bovino for Service as Priest of the Diocese of Norwich Ritual Mass for the Conferral of Holy Orders Cathedral of Saint Patrick Norwich, Connecticut June 27, 2020 10:30 a.m. -

Eastern Rite Catholicism

Eastern Rite Catholicism Religious Practices Religious Items Requirements for Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals Sacred Writings Organizational Structure History Theology RELIGIOUS PRACTICES Required Daily Observances. None. However, daily personal prayer is highly recommended. Required Weekly Observances. Participation in the Divine Liturgy (Mass) is required. If the Divine Liturgy is not available, participation in the Latin Rite Mass fulfills the requirement. Required Occasional Observances. The Eastern Rites follow a liturgical calendar, as does the Latin Rite. However, there are significant differences. The Eastern Rites still follow the Julian Calendar, which now has a difference of about 13 days – thus, major feasts fall about 13 days after they do in the West. This could be a point of contention for Eastern Rite inmates practicing Western Rite liturgies. Sensitivity should be maintained by possibly incorporating special prayer on Eastern Rite Holy days into the Mass. Each liturgical season has a focus; i.e., Christmas (Incarnation), Lent (Human Mortality), Easter (Salvation). Be mindful that some very important seasons do not match Western practices; i.e., Christmas and Holy Week. Holy Days. There are about 28 holy days in the Eastern Rites. However, only some require attendance at the Divine Liturgy. In the Byzantine Rite, those requiring attendance are: Epiphany, Ascension, St. Peter and Paul, Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Christmas. Of the other 15 solemn and seven simple holy days, attendance is not mandatory but recommended. (1 of 5) In the Ukrainian Rites, the following are obligatory feasts: Circumcision, Easter, Dormition of Mary, Epiphany, Ascension, Immaculate Conception, Annunciation, Pentecost, and Christmas. -

= P^Fkqp=Mbqbo=^Ka=M^Ri=Loqelalu=`Ero`E

+ = = p^fkqp=mbqbo=^ka=m^ri=loqelalu=`ero`e NEWSLETTER February, 2012 Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America Archpriest John Udics, Rector 305 Main Road, Herkimer, New York, 13350 Parish Web Page: www.cnyorthodoxchurch.org Saints Peter and Paul Orthodox Church Newsletter, February, 2012 This month’s Newsletter is in memory of Tillie Leve donated by Steve Leve. Parish Officer Contact Information Rector: Archpriest John Udics: (315) 866-3272 - [email protected] Committee President and Cemetery Director: John Ciko: (315) 866-5825 - [email protected] Committee Secretary: Subdeacon Demetrios Richards (315) 865-5382 – [email protected] Sisterhood President: Rebecca Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Choir Director: Reader John Hawranick: (315) 822-6517 – [email protected] Birthdays in February – God Grant You Many Years! 8 – Audrey Gale 20 – Wayne Nuzum 10 – Larissa Lyszczarz 22 – Martha Mamrosch 11 – Eileen Brinck 27 – Marilyn Stevens 13 – Emilee Penree Memory Eternal. 1 Julia Hladysz (1981) 13 Helen Brown (1993) 1 Leonard Corman (1991) 14 Julia Bruska (2000) 1 Dorothy Quackenbusg (2005) 15 Owen Dulak 2 John Garbera (1988) 16 John Yaworski (1977) 2 Helen Woods (1998) 16 Anna Kuzenech (1996) 4 Andrew Keblish (1975) 17 Andrew Yaneshak (1984) 4 Paul Shust Jr (2008) 18 Michael Kuncik (1980) 5 Stephen Sleciak Sr (1972) 21 Peter Slenska (1986) 5 Efrosina Krenichyn (1977) 22 Julia Hudyncia (1983) 5 Olga Nichols (1994) 23 Mary Mezick )2000) 8 Antonina Steckler (2007) 24 John Hubiak 10 Harry Hardish (1975) 26 Helen Pelko (2005) 10 Helen Halkovitch (1989) 28 Andrew Homyk (1984) 10 Theodosia Jago (2007) 28 Cornelius Mamrosch (1995) 13 Natalie Raspey (1973) 28 Louis Brelinsky (2004 13 Andrew Bobak (1978) + Questions and Answers 75. -

Elevation Design Guidelines: for Historic Homes in the Mississippi Gulf Coast Region

Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................1 4. Foundation Design Guidelines .....................29 Hurricane Katrina and Historic Properties in Coastal Mississippi ...... 1 Foundation Design............................................................................ 29 MDA Financial Assistance Programs .................................................. 2 Elevation Requirements ................................................................... 31 Relationship of MDA Financial Assistance Programs to Relationship of Foundation Design to Architectural Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act ....................... 2 Design and Historic Preservation ..................................................... 34 Purpose of Elevation Design Guidelines ........................................... 3 Foundation Screening Systems ........................................................ 35 Roles and Responsibilities .................................................................. 4 Permit Requirements ....................................................................... 36 Elevation Action Alternatives ............................................................. 5 Elevation Design Review Process ....................................................... 5 Working with an Elevation Design Consultant .................................. 6 5. Elevation Design – Next Steps .....................38 How to Complete a Successful Elevation Project .............................. 6 Design and Construction -

Formation for Eucharist: Eucharistic Prayer I ______

Formation for Eucharist: Eucharistic Prayer I _____________________________________________ The first eucharistic prayer is long, hard to follow, and ecumenically controversial. But it enjoys a long history, possesses surprising flexibility, and still stands as the first of the eucharistic prayers for use within the Roman Rite. For many centuries, the only eucharistic prayer in the Catholic mass was the one called the Roman Canon. It was a “canon” because it was the only one legislated for use. It was “Roman” because it probably originated and developed in Rome and its empire. The earliest record of it is in a work called “The Sacraments,” written by Saint Ambrose, the bishop of Milan (+397). Catholics reading that eucharistic prayer today can recognize its content, but are struck by its brevity and concision. Over the following centuries, sections were added to the beginning and the end of the prayer. Which elements had not yet developed in the fourth century? The preface dialogue, the Sanctus, the prayers for the living, the naming of the saints, and the prayers for the dead had not yet become customary. Those were added in subsequent redactions of the canon. Their addition – by various hands and at different points of history – has made the prayer hard to follow. It does not seem to flow smoothly from start to finish. Nor did the fourth century text possess a most significant element: the epiclesis. The priest did not explicitly ask God to send the Holy Spirit to change the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. Eucharistic Prayer I still does not have a clear epiclesis, and this has provoked concern among Eastern Rite Churches, which hold that the consecration comes with the epiclesis in their eucharistic prayers, not with the institution narrative.