Arun Sadhu (1942-2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.1 INTRODUCTION This Chapter Concentrates on the Buddhists

I l l nr h e : q u d d h i s t s Ei-rnfsjic i oeim t i t y I 3.1 INTRODUCTION This chapter concentrates on the Buddhists' ways of maintaining their new identity. The Mahars got a new framework for ethnic identity by embracing Buddhism. Patwardhan's (1973) study reported that 9 0 ’/. of the respondents from her sample declared themselves as Buddhists while only 1 0 ’/. considered themselves as Mahars. Interestingly, in the present study all the respondents (100’/.) have identified themselves as Buddhists. Gokhale's (1993) study maintains that the rejection of all Hindu traditions was the most important and outstanding feature of the self identification among Buddhists. In this context, Arun Sadhu (Nov. 1975) wrote in the Time* of India; "They (the Buddhists) seem to have got rid of their age old inferiority complex. They have a fresh sense of identity and a newly acquired confidence. What is more, the youth among them have completely shed the superstitions that had cramped their existence, and have adopted a more rational view of life". The Buddhists have made a great deal of effort to 70 learn and practise the customs, rites and rituals of Buddhism. Gokhale <1993) noted that the elite among them codified the new ideology through written words, new institutions, articles and books on Buddhism. The religious specialists were trained for guiding the people about Dhamma. They circulated pamphlets on the topic. The photograph of Dr. Ambedkar and Buddha can be found on the cover page of almost all the publications by the Buddhists. -

MAHARASHTRA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT LAUNCH Date: June 4, 2002 Venue: Y

MAHARASHTRA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT LAUNCH Date: June 4, 2002 Venue: Y. B. Chavan Centre, Mumbai The Maharashtra Human Development Report (MHDR) 2002 was launched at a release function held at the Y. B. Chavan Centre in Mumbai on June 4, 2002. The English version of the MHDR was released jointly by Dr. Ratnakar Mahajan, Executive President of the State Planning Board, and Dr. Brenda Gael McSweeney, Resident Representative of United Nations Development Programme-India and UN Resident Coordinator. A Marathi MHDR version was also released later in the day by Maharashtra Chief Minister Mr. Vilasrao Deshmukh, who could not attend the morning function. The Report is a collective initiative of the Government of Maharashtra, the Union Planning Commission and UNDP. The release function was followed by a panel discussion consisting of eminent government officials, social scientists and journalists. A question and answer session was also held, where participants from various backgrounds provided their inputs about MHDR and the HDR process. A multimedia presentation at the release vividly demonstrated the essence of MHDR to a packed auditorium. The presentation highlighted aspects of Maharashtra’s development, namely, trends and prospects in population dynamics, conditions of health and nutrition, educational scenario, gender issues, and the nexus between growth and human development. The MHDR 2002 contends that Maharashtra has made progress in poverty eradication, and in the fields of education, health, employment and people’s participation in local-level governance. Participation and role of women in public life have shown improvement. Nevertheless, certain areas demand active governmental action and a participative civil society to ensure that the most vulnerable groups benefit from the developmental process. -

Festival of Letters 2014

DELHI Festival of Letters 2014 Conglemeration of Writers Festival of Letters 2014 (Sahityotsav) was organised in Delhi on a grand scale from 10-15 March 2014 at a few venues, Meghadoot Theatre Complex, Kamani Auditorium and Rabindra Bhawan lawns and Sahitya Akademi auditorium. It is the only inclusive literary festival in the country that truly represents 24 Indian languages and literature in India. Festival of Letters 2014 sought to reach out to the writers of all age groups across the country. Noteworthy feature of this year was a massive ‘Akademi Exhibition’ with rare collage of photographs and texts depicting the journey of the Akademi in the last 60 years. Felicitation of Sahitya Akademi Fellows was held as a part of the celebration of the jubilee year. The events of the festival included Sahitya Akademi Award Presentation Ceremony, Writers’ Meet, Samvatsar and Foundation Day Lectures, Face to Face programmmes, Live Performances of Artists (Loka: The Many Voices), Purvottari: Northern and North-Eastern Writers’ Meet, Felicitation of Akademi Fellows, Young Poets’ Meet, Bal Sahiti: Spin-A-Tale and a National Seminar on ‘Literary Criticism Today: Text, Trends and Issues’. n exhibition depicting the epochs Adown its journey of 60 years of its establishment organised at Rabindra Bhawan lawns, New Delhi was inaugurated on 10 March 2014. Nabneeta Debsen, a leading Bengali writer inaugurated the exhibition in the presence of Akademi President Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, veteran Hindi poet, its Vice-President Chandrasekhar Kambar, veteran Kannada writer, the members of the Akademi General Council, the media persons and the writers and readers from Indian literary feternity. -

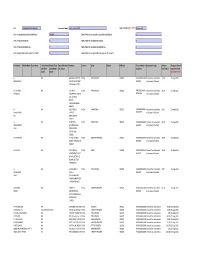

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

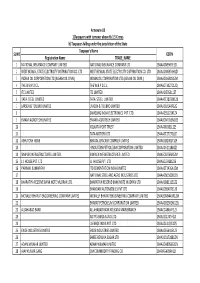

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Dr. Deepak Pawar

Dr. Deepak Pawar Department of Civics & Politics, Mumbai University Pherozshah Mehta Bhavan, Department of Civics & Politics, Kalina Campus, University of Mumbai, Santacruz (E), Mumbai – 400098 [email protected] 1 EDUCATION 1988 SSC Sarvoday Vidyalaya Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai 1990 HSC Kelkar Education Trust‟s V. G. Vaze College of Arts, Mulund, Mumbai Science & Commerce 1993 B. A. Kelkar Education Trust‟s V. G. Vaze College of Arts, Mulund, Mumbai Science & Commerce 1995 M. A. Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai Mumbai 1997 NET University Grants Commission Qualified 2013 PhD Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai Mumbai Teaching experience: 24 years Research experience: 24 years Subjects taught: Language Policy and Politics in India Language Policy and Politics: A comparison of India and Pakistan Public Administration Political Theory Theories of International Relations Indian Constitution Political Thoughts in Maharashtra Western Political Thought Local Self-government (with special reference to Maharashtra) Understanding Politics through Cinema Rights in the context of Maharashtra Dalit Movement in India Regionalism and Regional disparities in Maharashtra 2 Indian Government and Policy Contribution in teaching methods: Chalk and Talk method Assignments Classroom Debates Regular Class Test Visit to Documentation Centers for Screening of Documentaries Presentations Book Reviews Newspaper Clippings Poster Presentation Industrial Visits Participation in conference Evaluation Techniques: Class Test Home Assignments Viva Presentations PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Position Institution Assistant Professor Department of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai: 1. Language Policy and Politics 2. State Politics. Lecturer K. J. Somaiya College of Arts & Commerce, Mumbai: 1. Political Theory, 2. Politics in Maharashtra 3. International Relations. President Marathi Abhyas Kendra (Marathi Study Centre): An organization working for the promotion Marathi language and culture. -

Current Affairs September 2017 PDF Capsule

Current Affairs September 2017 PDF Capsule Current Affairs PDF: September 2017 Current Affairs for Competitive Exam Contents INDIAN AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................................................ 3 PLACES IN NEWS ......................................................................................................................................................... 47 FOREIGN VISITS .......................................................................................................................................................... 51 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS....................................................................................................................................... 53 SUMMITS & CONFERENCES ..................................................................................................................................... 66 RANKINGS & REPORTS ............................................................................................................................................. 71 BANKING & FINANCE ................................................................................................................................................. 74 BUSINESS ....................................................................................................................................................................... 83 AWARDS & RECOGNITIONS .................................................................................................................................... -

Name : SUHAS PALSHIKAR

Name: SUHAS PALSHIKAR Designation: PROFESSOR, Dept of Politics and Public Administration, University of Pune Contact: [email protected]; [email protected] B-703, Rohan Garima, Off S.B. Rd., Pune 411016 Tel. (R) +91 20 25636995; (O) +91 20 25690815 Qualification: B.A. (Pune); 1976; M.A. (Pune); 1978; M. Phil. (Pune); 1982; Ph. D. (Pune); 1986 Professional Experience: Taught for 11 years--undergraduate level (S. P. College, Pune):1978-89 Faculty, University of Pune, since 1989 Specialisation: Political Process in India, Politics of Maharashtra, Political Sociology of democracy Research supervision: Ph. D. (completed): Ten; working: Two M. Phil. (completed): Thirteen; working: Two Research Work: A) Work Completed 1. Caste and Social Mobility: A case study of Pune city; CSS, University of Pune, (2006-08); Co-Investigator: Dr Rajeshwari Deshpande 2. A study of Political Parties in Maharashtra; SAP, 3rd Phase, (2005- 2007), Co-Investigators: Nitin Birmal and Suhas Kulkarni; Marathi book published. 3. Coalition Politics in Maharashtra, UPIASI, Delhi (2004-2006); Co-Investigator: Nitin Birmal; Report submitted to UPIASI. 4. State of Democracy in South Asia, Joint coordinator, A project of the Lokniti programme of CSDS, Ford Foundation and EU-India Programme, ( 2002-2006); Co-Investigators: Yogendra Yadav and Peter R. De Souza; Report prepared and submitted to Donors. 5. Study of Local Government Elections in Maharashtra, Special Assistance Programme, 2nd Phase, (2001-02); Co- Investigator: Nitin Birmal. Marathi book and English article published 6. Pune: From City to Metropolis, Special Assistance Programme, 2nd Phase, (1999-2002); Co-Investigators: Rajeshwari Deshpande and Nitin Birmal. 7. Politics of Marginalized Groups: A Study of Aurangabad and Ahmednagar districts; Major Research Project Scheme of UGC; (1997-2000). -

UBCOMFSI.4 FYB.Com Business Communication Semester I

31 F.Y.B.COM. BUSINESS COMMUNICATION SEMESTER - I SUBJECT CODE : UBCOMFSI.4 © UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Dr. Suhas Pednekar Vice-Chancellor University of Mumbai, Mumbai Dr. Kavita Laghate Anil R Bankar Professor cum Director, Associate Prof. of History & Asst. Director & Institute of Distance & Open Learning, Incharge Study Material Section, University of Mumbai, Mumbai IDOL, University of Mumbai, Mumbai Programme Co-ordinator : Priya Pawaskar Asst. Professor in English IDOL, University of Mumbai. Course Co-ordinator : Dr. Savita Patil & Course Writer Head, Department of English, Elephistone College, Mumbai Course Writers : Dr. K. H. Pawar : Prof. YogeshAnvekar Department of English Head of Department of English M.D. College, Parel, G..N. Khalsa College, Mumbai - 400012 Matunga, Mumbai - 400019 : Dr. Ambreen Kharbe : Dr. Vijay Patil Department of English Department of English, G.M. Momin College, Nalanda Nitya Kala Mahavidyalay Bhinwandi, Dist. Thane Vile Parle (W), Mumbai - 400049 : Dr. S. D. Sargar : Prof. Kalpana N. Shelke Head, Department of English Head, Department of English, Veer Wajekar Arts, Science & Barns College of Arts, Commerce College, Science & Commerce, Phunde, Dist - Raigad - 400702 Panvel, Navi Mumbai Course Writer & Editor : Dr. Shikha Dutta Head, Department of English “Vivekanand Education Society's College of Arts, Science, and Commerce, Sindhi Society,“Chembur, Mumbai-400071 December, 2020 F.Y.B.COM. Business Communication Published by : Professor cum Director Institute of Distance and Open Learning , University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai - 400 098. DTPipin Enterprises Composed : Ashwini Arts GurukripaTantia Jogani Chawl, Industrial M.C. Chagla Estate, Marg, Unit Bamanwada, No. 2, VileGround Parle (E), Floor, Mumbai Sitaram - 400 Mill 099. Compound,Pace Computronics "Samridhi"J.R. -

Trust Diminishes As an Editor Is Knocked Off His Pedestal

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 July-September 2017 Volume 9 Issue 3 Rs 50 Trust diminishes as an editor is knocked off his pedestal The Economic and Political Weekly is one of India’s most respected academic and journalistic publications. It now finds itself embroiled in one of India’s most unseemly media controversies. CONTENTS • An editor’s exit reflects Ranjona Banerji provides the background and brings us up to perils of investigative speed on the latest developments journalism / Bharat Dogra • Needed: Sentiments of orn from the Economic Weekly started by Sachin Chaudhuri in 1949, the daring and social vigilance / Economic and Political Weekly emerged when Chaudhuri closed down the Sakuntala Narasimhan Economic Weekly in 1966. Friends and well-wishers got together to form the • Can ‘peace-mongering’ B ever be news? / Sakuntala Sameeksha Trust, so that the journal could run freely and without interference. Sadly, the last two editors have left because of problems of interference from Narasimhan the Trust. First C. Rammanohar Reddy quit after 10 years with EPW. Admirers • Keeping options open in thought the ship would steady when Paranjoy Guha Thakurta was appointed a changed global order / Shastri Ramachandaran last year. Instead, his resignation has really shaken not just the EPW community but the larger world of the media and academia. • Time higher education is given the focus it deserves / Guha Thakurta is a formidable business and investigative journalist. His Mario Noronha work has targeted some of India’s biggest industrial and business houses from • Getting the better of online Sahara to the Ambanis. -

Paushak 2008-2009

CIN L51909GJ1972PLC044638 Company Name PAUSHAK LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 08-Aug-2013 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 344344 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husb Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First and Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD-MON-YYYY) A NA 6/9-A KAJA STREET INDIA TAMIL NADU 625001 PAUS000000000 Amount for unclaimed 10.00 25-Aug-2016 ARUMUGAM SOUTH VELI STREET 0005091 and unpaid dividend MADURAI 625001 A C A AIYAM NA C/O AR A INDIA TAMIL NADU 626001 PAUS00000000 Amount for unclaimed 16.00 25-Aug-2016 PERUMAL KARUPPIAH NADAR 00005144 and unpaid dividend 224 TEPPAM NORTH VIRUDHUNAGAR- 626001 A NA 309 DOMLUR INDIA KARNATAKA 560071 PAUS00000000 Amount for unclaimed 8.00 25-Aug-2016 GANGADHAR LAYOUT 00005277 and unpaid dividend AN BANGALORE- 560071 A NA ST MARY'S INDIA KARNATAKA 560066 PAUS000000000 Amount for unclaimed 22.00 25-Aug-2016 IRUDAYANAT BUILDING MAIN 0004973 and unpaid dividend HAN ROAD CROSS WHITEFIELD- 560066 A K MAHIPATI NA 4-7-287 ISAMIA INDIA ANDHRA PRADESH 500027 PAUS000000000 Amount for unclaimed 16.00 25-Aug-2016 BAZAR HYDERABAD- 0005090 and unpaid dividend 500027 A K MALIK NA 3-C DHRUVA INDIA -

Bibliography Primary Sources A) Newspapers Rashtraveer

Bibliography Primary Sources A) Newspapers Rashtraveer, Shivachhatrapati, Chhatrapati, Tarun Maratha, Garibancha Kaivari, Bhagava Zenda, Shrishivasmarak, Vijayi Maratha, Deen Mitra, Jagruti, Hunter, Kaivari, Kesari, Maratta, and Navyug ( From 1900 to 1948). Sakal, Pudhari, Times of India, Loksatta, and Mahrashtra Times (1940 to 1980). B) Government Documents Report of the Deccan riots of 1875, Census of the Central Provinces, Bombay Provinces, District statistical abstracts, reports of the committee on education and local self rule, Legislative Council debates (1920 to 1940) of Bombay Presidency, Mahrastra State Legislative Assembly and Council debates (1960 to 1980), GOM statistics on cooperatives (1960 to 1980). C) Other Sources Personal diaries, photographs, documentary on Military Apshinge, Momentos, commendations of ex-military personnel. Pamphlets and other documents of the All India Maratha Education Conference, Shri Shivaji Maratha School, Shivaji Military Preperatory School, SSPMS, Poona Urban Cooperative Bank, Shahu Papers (Vol 1 to 10), Chhatrapati Mela Padya Sangrah (Collection of poems published by Keshavrao Jedhe in 1928), Memoirs of Latte (the secretary to Shahu Maharaj), Kolhapur Daftar Aithehasik Sadhane (Historial material of Kolhapur Princely State) D) Interviews Academics Dr, Prachi Deshpande (Columbia University), Prof Sakhela (University of Johannesburg), Prof. Tina Uys (University of Johannesburg), Prof. Burowoy (then President of American Sociological Association) Prof Donald Attwood (visiting professor to University of Pune) , Prof Suhas Palshikar, Rajeshwari Deshpande and 316 Dr Kulkari (all from political science department, university of Pune), Prof Dhanagre (retd), Ram Bapat (retired), Prof Uttam Bhoite (president of Indian Sociological Society), Prof. Sharmila Rege (Univeristy of Pune), Prof. ANiket Jaware (University of Pune), Prof Salunkhe (Shivjai University), Prof Kolhe (retd). -

Current Affairs - September 2017

Current Affairs - September 2017 Current Affairs ─ September 2017 This is a guide to provide you a precise summary and a huge collection of Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) covering national and international current affairs for the month of September 2017. This guide will help you in preparing for Indian competitive examinations like Bank PO, Banking, Railway, IAS, PCS, UPSC, CAT, GATE, CDS, NDA, MCA, MBA, Engineering, IBPS, Clerical Grade and Officer Grade, etc. Audience Aspirants who are preparing for different competitive exams like Bank PO, Banking, Railway, IAS, PCS, UPSC, CAT, GATE, CDS, NDA, MCA, MBA, Engineering, IBPS, Clerical Grade, Officer Grade, etc. Even though you are not preparing for any exams but are willing to have news encapsulated in a roll, which you can walk through within 30 minutes, then we have put all the major points for the whole month in a precise and interesting way. Copyright and Disclaimer Copyright 2017 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial.