There's Just One Hitch, Will Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“My” Hero Or Epic Fail? Torchwood As Transnational Telefantasy

“My” Hero or Epic Fail? Torchwood as Transnational Telefantasy Melissa Beattie1 Recibido: 2016-09-19 Aprobado por pares: 2017-02-17 Enviado a pares: 2016-09-19 Aceptado: 2017-03-23 DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Para citar este artículo / to reference this article / para citar este artigo Beattie, M. (2017). “My” hero or epic fail? Torchwood as transnational telefantasy. Palabra Clave, 20(3), 722-762. DOI: 10.5294/pacla.2017.20.3.7 Abstract Telefantasy series Torchwood (2006–2011, multiple production partners) was industrially and paratextually positioned as being Welsh, despite its frequent status as an international co-production. When, for series 4 (sub- titled Miracle Day, much as the miniseries produced as series 3 was subti- tled Children of Earth), the production (and diegesis) moved primarily to the United States as a co-production between BBC Worldwide and Amer- ican premium cable broadcaster Starz, fan response was negative from the announcement, with the series being termed Americanised in popular and academic discourse. This study, drawn from my doctoral research, which interrogates all of these assumptions via textual, industrial/contextual and audience analysis focusing upon ideological, aesthetic and interpretations of national identity representation, focuses upon the interactions between fan cultural capital and national cultural capital and how those interactions impact others of the myriad of reasons why the (re)glocalisation failed. It finds that, in part due to the competing public service and commercial ide- ologies of the BBC, Torchwood was a glocalised text from the beginning, de- spite its positioning as Welsh, which then became glocalised again in series 4. -

Actors Anonymous of Legion the Watching from Thrill Different a Be Will That Me, for But, Audience

NOTES FROM THE DREAM FACTORY BY TOM ROSTON he first met when they were both in the 2002 Broadway play Burn This. And although we’re talking about Burrell, Norton might as well be speaking about his own brilliant debut in 1996’s Primal Fear, when he, seemingly out of nowhere, rocketed to recognition. “It is a very particular kind of excitement,” he says. “There is no sense of the artifice. That’s what’s really thrilling.” I am always hoping for pure moments when I watch a movie: those times when my disbelief is so entirely suspended that I forget that I’m watching one. Going into a theater, I often feel overwhelmed with baggage—who the main actor slept with last week, how the director mortgaged his house to get the movie made, and how the production designer only used three shades of green on the set. It even bugs me that once I like a director or an actor, I expect something from him or her, and so the work has an added layer of self-consciousness. When the lights go down, it’s hard to wash the slate entirely clean and just watch. That’s why my eyes tend to drift toward the margins for something surprising. And, often, I see it in an actor whom I know nothing about, and who brings something deeper and richer to his character even though he may have just two minutes of screen time. This may seem random (and that’s the point), but do you remember in the Will Smith movie Hitch, which I just caught on DVD, that there’s this misogynist asshole who is, well, such an asshole? Actor Jeffrey Donovan gets it just right. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 CAPTURE THE FLAG Actors: Rasmus Hardiker. Sam Fink. Paul Kelleher. Adam James. Derek Siow. Andrew Hamblin. Oriol Tarragó. Bryan Bounds. Ed Gaughan. Actresses: Lorraine Pilkington. Philippa Alexander. Jennifer Wiltsie. CARE OF FOOTPATH 2 Actors: Deepp Pathak. Jaya Karthik. Kishan S. S.. Dingri Naresh. Actresses: Avika Gor. Esha Deol. CARL(A) Actors: Gregg Bello. Actresses: Laverne Cox. CAROL Actors: Jake Lacy. John Magaro. Cory Michael Smith. Kevin Crowley. Nik Pajic. Kyle Chandler. Actresses: Cate Blanchett. -

The Hollywood Reporter November 2015

Reese Witherspoon (right) with makeup artist Molly R. Stern Photographed by Miller Mobley on Nov. 5 at Studio 1342 in Los Angeles “ A few years ago, I was like, ‘I don’t like these lines on my face,’ and Molly goes, ‘Um, those are smile lines. Don’t feel bad about that,’ ” says Witherspoon. “She makes me feel better about how I look and how I’m changing and makes me feel like aging is beautiful.” Styling by Carol McColgin On Witherspoon: Dries Van Noten top. On Stern: m.r.s. top. Beauty in the eye of the beholder? No, today, beauty is in the eye of the Internet. This, 2015, was the year that beauty went fully social, when A-listers valued their looks according to their “likes” and one Instagram post could connect with millions of followers. Case in point: the Ali MacGraw-esque look created for Kendall Jenner (THR beauty moment No. 9) by hairstylist Jen Atkin. Jenner, 20, landed an Estee Lauder con- tract based partly on her social-media popularity (40.9 million followers on Instagram, 13.3 million on Twitter) as brands slavishly chase the Snapchat generation. Other social-media slam- dunks? Lupita Nyong’o’s fluffy donut bun at the Cannes Film Festival by hairstylist Vernon Francois (No. 2) garnered its own hashtag (“They're calling it a #fronut,” the actress said on Instagram. “I like that”); THR cover star Taraji P. Henson’s diva dyna- mism on Fox’s Empire (No. 1) spawns thousands of YouTube tutorials on how to look like Cookie Lyon; and Cara Delevingne’s 22.2 million Instagram followers just might have something do with high-end brow products flying off the shelves. -

Hollywood Loving

HOLLYWOOD LOVING Kevin Noble Maillard* INTRODUCTION It is no coincidence that Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner1 was released the same year that Loving v. Virginia2 was decided: 1967. It was the first time in American history that interracial marriage was collectively recognized as a legitimate, intimate choice between two adults. This public exposition of racial intermixture exposed a collective memory of racial heterogeneity previously treated in law and popular culture as suspect. Collectively, there were few possibilities, expressions, or affirmative realizations of interracially intimate culture before 1967. Some cases, like McLaughlin v. Florida3 and Perez v. Sharp,4 successfully overturned discriminatory laws targeting interracial couples, but the vast majority, like Naim v. Naim,5 upheld them. * Professor of Law, Syracuse University. Thank you to the student editors of the Fordham Law Review and to the Fordham Professors Robin Lenhardt and Tanya Katerí Hernández for organizing the Symposium entitled Fifty Years of Loving v. Virginia and the Continued Pursuit of Racial Equality held at Fordham University School of Law on November 2–3, 2017. Additional thanks to my excellent Symposium panel for the discussion: Solangel Maldonado, Nancy Buirski, Leora Eisenstadt, and Regina Austin. And thank you to Rose Cuison Villazor, Darren Rosenblum, and Bridget Crawford for their insight, encouragement, and expertise. For an overview of the Symposium, see R.A. Lenhardt, Tanya K. Hernández & Kimani Paul- Emile, Foreword: Fifty Years of Loving v. Virginia and the Continued Pursuit of Racial Equality, 86 FORDHAM L. REV. 2625 (2018). 1. GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER (Columbia Pictures 1967) (starring Sidney Poitier, Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, and Katharine Houghton). -

Holding up Half the Sky Global Narratives of Girls at Risk and Celebrity Philanthropy

Holding Up Half the Sky Global Narratives of Girls at Risk and Celebrity Philanthropy Angharad Valdivia a Abstract: In this article I explore the Half the Sky (HTS) phenomenon, including the documentary shown on the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) network in 2014. I explore how the girls in whose name the HTS movement exists are repre- sented in relation to Nicholas Kristoff and six celebrity advocates. This analysis foregrounds Global North philanthropy’s discursive use of Global South girls to advance a neoliberal approach that ignores structural forces that account for Global South poverty. The upbeat use of the concept of opportunities interpellates the audience into participating in individualized approaches to rescuing girls. Ulti- mately girls are spoken for while celebrities gain more exposure and therefore increase their brand recognition. Keywords: Global South, Media Studies, neoliberalism, philitainment, representation, white savior b Girls figure prominently as a symbol in global discourses of philanthropy. The use of girls from the Global South lends authority and legitimacy to Western savior neoliberal impulses, in which the logic of philanthropy shifts responsibility for social issues from governments to individuals and corpo- rations through the marketplace, therefore help and intervention are “encouraged through privatization and liberalization” (Shome 2014: 119). Foregrounding charitable activities becomes an essential component of celebrity branding and corporate public relations that seek representation of their actions as cosmopolitan morality and global citizenry. Focusing on the Half the Sky (HTS) phenomenon that culminated in a documentary by Maro Chermayeff (2012) shown on the PBS network in 2014, in this article I examine the agency and representation of six celebrity advocates in relation to the girls in whose name the HTS movement exists. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

Film Stars Don't Die in Liverpool

FILM STARS DON'T DIE IN LIVERPOOL Written by Matt Greenhalgh 1. 1 INT. LEADING LADY’S DRESSING ROOM - NIGHT 1 Snug and serene. An illuminated vanity mirror takes centre stage emanating a welcoming glamorous glow. A SERIES OF C/UP’s: A TDK AUDIO TAPE inserted into a slim SONY CASSETTE PLAYER immediately placing us in the late 70’s/early 80’s. A CHIPPED VARNISHED FINGER NAIL presses play.. ‘Song For Guy’ by Elton John (Gloria’s favourite track) drifts in... OUR LEADING LADY sits in the dresser. Find her through shards of focus and reflections as she transforms.. warming her vocal chords as she goes: GLORIA (O.C.) ‘La Poo Boo Moo..’ Eye-line pencil; cherry-red lipstick; ‘Saks of Fifth Avenue’ COMPACT MIRROR, intricately engraved with “Love Bogie ’In A Lonely Place’ 1950”; Elnett hair laquer; Chanel perfume. A larger BROKEN HAND-MIRROR. A GOLDEN LOVE HEART PENDANT (opens with a sychronised tune). All Gloria’s ‘tools’ procured from a TATTY GREEN WASH-BAG, a trusted witness to her ‘process’ probably a thousand times or more. GLORIA (O.C.) (CONT’D) ‘Major Mickey’s Malt Makes Me Merry.’ Costume: Peek at pale flesh and slim limbs as she climbs into a black, pleated wrap around dress with a plunging neckline; black stockings and princess slippers.. the dress hangs loose, too loose.. the belt tightened as far as it can go. A KNOCK ON THE DOOR STAGE MANANGER (V.O.) Five minutes Miss Grahame. GLORIA (O.C.) Thanks honey. Gloria’s tongue CLUCKS the roof of her mouth in approval, it’s one of her things. -

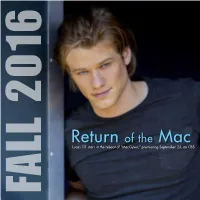

Return of The

Return of the Mac Lucas Till stars in the reboot of “MacGyver,” premiering September 23, on CBS. FALL 2016 FALL “Conviction” ABC Mon., Oct. 3, 10 p.m. PLUG IN TO Right after finishing her two-season run as “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” Hayley Atwell – again sporting a flawless THESE FALL PREMIERES American accent for a British actress – BY JAY BOBBIN returns to ABC as a smart but wayward lawyer and member of a former first family who avoids doing jail time by joining a district attorney (“CSI: NY” alum Eddie Cahill) in his crusade to overturn apparent wrongful convictions … and possibly set things straight with her relatives in the process. “American Housewife” ABC Tues., Oct. 11, 8:30 p.m. Following several seasons of lending reliable support to the stars of “Mike & Molly,” Katy Mixon gets the “Designated Survivor” ABC showcase role in this sitcom, which Wed., Sept. 21, 10 p.m. originally was titled “The Second Fattest If Kiefer Sutherland wanted an effective series follow-up to “24,” he’s found it, based Housewife in Westport” – indicating on the riveting early footage of this drama. The show takes its title from the term used that her character isn’t in step with the for the member of a presidential cabinet who stays behind during the State of the Connecticut town’s largely “perfect” Union Address, should anything happen to the others … and it does here, making female residents, but the sweetly candid Sutherland’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development the new and immediate wife and mom is boldly content to have chief executive. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

The Intersection of Gender & Ethnicity on Latinas' Workplace Sexual

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title “WE DON’T THINK OF IT AS SEXUAL HARASSMENT”: The Intersection of Gender & Ethnicity on Latinas’ Workplace Sexual Harassment Claims Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0x57d7tc Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 33(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Suero, Waleska Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/C7331027616 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “WE DON’T THINK OF IT AS SEXUAL HARASSMENT”: The Intersection of Gender & Ethnicity on Latinas’ Workplace Sexual Harassment Claims By Waleska Suero* “[T]hat’s right, we don’t think of it as sexual harassment . .”1 In the workplace, sexual harassment is broadly defined as the mak- ing of “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment of a sexual nature.”2 Workplace sexual harassment may arise as a single occurrence where sexual favors are de- manded in exchange for hiring, promotions, or retention.3 It may also be ongoing in the form of continuous sexually suggestive remarks, looks, or touches.4 Either way, in society there are unequal power dynamics be- tween the sexes that play out in the employment context where unequal power dynamics can result in the threat of job security if the woman addresses the unwelcomed statements or gestures.5 Despite this broad understanding of the term “sexual harassment,” differences in race and ethnicity, gender, class, education, and economic status shape how differ- ent groups experience sexual harassment. The focus of this paper is workplace sexual harassment of wom- en at the intersection of gender and ethnicity, specifically pertaining to Latin American women.6 Challenging the pervasive stereotype of the * Georgetown University Law Center, J.D. -

Mike Curb College of Arts, Media, and Communication

Mike Curb College of Arts, Media and Communication Top 30 Film Schools in the World Variety Top 25 Music Schools in the U.S. The Hollywood Reporter LLEGE ANDA, CURB CO MIKE OF ARTS, MEDI COMMUNICATION Mike Curb College of Arts, Media and Communication Mike Curb College of Arts, Media and Communication TABLE OF Departments Art CONTENTS Cinema and Television Arts Communication Studies Journalism Music Theatre LA Close Up A Degree in the Creative Capital Career Options CSUN Alumni Outstanding Value Students Outside California Scholarships Programs Offered California State University Entertainment Alliance Mike Curb College of Arts, Media and Communication CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE MIKE CURB COLLEGE OF ARTS, MEDIA, AND COMMUNICATION At CSUN’s Mike Curb College of Arts, Media, and Communication (MCCAMC), we know from experience what our students can do when we give them what they need. Like small class sizes in buildings fitted with the latest technologies. Or courses taught by faculty with vast industry credentials. That’s not counting our deep, decades-long connections to the entertainment business, either. MCCAMC alumni have been behind some of the era’s biggest box-office hits and classics. They’ve entered the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and won GRAMMYS, Emmys and Golden Globes. You’ve seen them on television and in theatres. They are stars and innovators, artists and executives. And before that… They were students, just dreaming of that defining moment: the click, the spark, the beginning of big new things. It’s here, at MCCAMC, where they finally found it. And we invite you, in these coming pages, to discover why.