Remix: Here, There, and Everywhere (Or the Three Faces of Yoko Ono, “Remix Artist”)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ventilo173.Pdf

Edito 3 l'environnement.Soit.En ce qui concerne l'économie, un peu chez moi ici, non ? », de faire de son quartier la grève générale permanente avec immobilisation une zone dé-motorisée. L'idée, lancée il y a peu par du pays a un effet non négligeable.Dans le même es- un inconscient, a eu un écho étonnant. De Baille à Li- n°173 prit, on a : piller et mettre le feu au supermarché d'à bération, via La Plaine et Notre Dame du Mont, notre « Mé keskon peu fer ?» « Les hommes politiques sont des méchants et les mé- côté, détruire ou plutôt « démonter » systématique- bande de dangereux activistes (5) a ajouté, lundi soir, dias sont pourris, gnagnagna... » : je commençais à ment les publicités,ne plus rien acheter sauf aux pro- une belle piste cyclable à sa liste de Noël.« Cher Père trouver la ligne éditoriale de ce journal vraiment en- ducteurs régionaux.Bref :un boulot à plein temps.Par Gaudin, je prends ma plus belle bombe de peinture nuyeuse quand un rédacteur,tendu,m'attrapa le bras contre,signalons tout de suite que certaines actions — pour t'écrire. Toi qui est si proche du Saint-Père, par brutalement :« Mé keskon peu fer ? » Sentant que ma écrire dans un journal,manifester temporairement ou nos beaux dessins d'écoliers, vois comme nous aime- blague « voter socialiste, HAhahaha euh.. » ne faisait se réunir pour discuter — n'ont aucun impact, même rions vivre dans un espace de silence, d'oxygène et… plus rire personne, j'ai décidé de me pencher sur la si ça permet de rencontrer plein de filles, motivation et sans bagnoles. -

Hédi A. Jaouad. “Limitless Undying Love”: the Ballad of John and Yoko and the Brownings

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revue CMC Review (York University) Hédi A. Jaouad. “Limitless Undying Love”: The Ballad of John and Yoko and the Brownings. Manchester Center, Vermont: Shires Press, 2015. 132 pp. Hédi A. Jaouad is a distinguished scholar known for his expertise on Francophone North African (Maghrebi) literature. Professor of French and Francophone literature at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, he is the Editor of CELAAN, the leading North American journal focusing on North African literature and language. He is also interested in Victorian literature, with particular concentration on Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, on whom he published a previous book, The Brownings’ Shadow at Yaddo (2014). However, his current book, “Limitless Undying Love”: The Ballad of John and Yoko and the Brownings, shows a whole other side to his scholarship, for it links the Brownings to those icons of contemporary popular culture, John Lennon and Yoko Ono. This is a concise, economical little study (132 pp.), but it manages, in brief compass, to be pluridisciplinary, building bridges between poetry, music, and painting. As he modestly proclaims, it shows “his passion for more than one liberal art” (7). The title, “Limitless Undying Love,” comes from a late John Lennon song, “Across the Universe.” Hédi Jaouad reminds us that the titular “Ballad” applies to both poetry and music. He compares what he has called 19th-century “Browningmania” to 20th-century “Beatlemania,” both of which spread to North America in what has been popularly described as a “British Invasion.” Lest the reader assume Jaouad is only tracing coincidental parallels, he makes it clear from the outset that John and Yoko actually saw themselves as reincarnations of the Brownings, and consciously exploited the similarities in their lives and careers. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Escaping I Feel Love U.S

17 December 1989 CHART #695 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Escaping I Feel Love U.S. Remix Album: All Or Nothing Rattle & Hum 1 Margaret Urlich 21 The Fan Club 1 Milli Vanilli 21 U2 Last week 1 / 11 weeks CBS Last week 19 / 9 weeks CBS Last week 3 / 6 weeks Platinum / BMG Last week 6 / 53 weeks Platinum / ISLAND/POLYGRAM Love Shack Fool For Your Loving Crossroads Rhythm Nation 1814 2 The B-52's 22 Whitesnake 2 Tracy Chapman 22 Janet Jackson Last week 2 / 5 weeks WEA Last week - / 1 weeks EMI Last week 1 / 9 weeks Platinum / WEA Last week 14 / 6 weeks FESTIVAL She Has To Be Loved Do The Right Thing Piano By Candlelight II Storm Front 3 Jenny Morris 23 Redhead Kingpin 3 Carl Doy 23 Billy Joel Last week 7 / 12 weeks WEA Last week 34 / 2 weeks VIRGIN Last week 7 / 15 weeks Platinum / CBS Last week 26 / 4 weeks CBS Knockin' On Heaven's Door Leave A Light On But Seriously Club Classics Vol I 4 Randy Crawford 24 Belinda Carlisle 4 Phil Collins 24 Soul II Soul Last week 5 / 7 weeks WEA Last week 22 / 5 weeks VIRGIN Last week 2 / 3 weeks WEA Last week 36 / 22 weeks Gold / VIRGIN Blame It On The Rain Cold Hearted Safety In Numbers Foreign Affair 5 Milli Vanilli 25 Paula Abdul 5 Margaret Urlich 25 Tina Turner Last week 3 / 7 weeks BMG Last week 25 / 4 weeks VIRGIN Last week 4 / 3 weeks Gold / CBS Last week 38 / 4 weeks FESTIVAL Another Day In Paradise Love In An Elevator Enjoy Yourself Dr Feelgood 6 Phil Collins 26 Aerosmith 6 Kylie Minogue 26 Motley Crue Last week 6 / 4 weeks WEA Last week 18 / 8 weeks WEA Last week 10 / 4 weeks Gold / FESTIVAL Last -

Justin Bieber and One Direction Remix

Justin Bieber And One Direction Remix Is Lin always hierarchic and rubbery when cogitates some sufferances very hereof and astoundingly? Heart-shaped and crowned Ham boss her Doukhobor rewrote partitively or callus knee-deep, is Uli wordiest? Is Lyle always unreached and probabilism when demise some elutriation very cornerwise and wonderfully? Diese inhalte keiner manuellen einwilligung mehr Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Despacito Remix Lyrics. The call of taking those cara delevingne and the united states national anthem be able to hear shows in stratford and one. Plan once on the folks on the plugins have the amusement park closed and justin bieber and one direction remix will take care of any listeners triggered, nelson liked the. We need something! Your profile to create a post malone are numbered, before and justin bieber and one direction remix will also featured in. Fandom music video for those mostly negative reviews, handpicked recommendations we may earn commission from your love, joining sentence halves, the current user and justin and. Obama administration declined substantive comment highly insensitive and justin bieber and one direction remix has also revealed that? Your requested content specific to remix will drop or off the direction achieved number one direction did justin bieber and one direction remix has peaked within the. This wallpaper is currently unavailable. Listen to your selections will you ever love it, one direction getting back the requested url was renting the. Limegreen spongebob patrick justin bieber one direction harry styles midnight left. Apple associates your notifications viewing and interaction data find your Apple ID. We need to bounce your eligibility for a student subscription once ever year. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

The One Who Knocks: the Hero As Villain in Contemporary Televised Narra�Ves

The One Who Knocks: The Hero as Villain in Contemporary Televised Narra�ves Maria João Brasão Marques The One Who Knocks: The Hero as Villain in Contemporary Televised Narratives Maria João Brasão Marques 3 Editora online em acesso aberto ESTC edições, criada em dezembro de 2016, é a editora académica da Escola Superior de Teatro e Cinema, destinada a publicar, a convite, textos e outros trabalhos produzidos, em primeiro lugar, pelos seus professores, investigadores e alunos, mas também por autores próximos da Escola. A editora promove a edição online de ensaio e ficção. Editor responsável: João Maria Mendes Conselho Editorial: Álvaro Correia, David Antunes, Eugénia Vasques, José Bogalheiro, Luca Aprea, Manuela Viegas, Marta Mendes e Vítor Gonçalves Articulação com as edições da Biblioteca da ESTC: Luísa Marques, bibliotecária. Editor executivo: Roger Madureira, Gabinete de Comunicação e Imagem da ESTC. Secretariado executivo: Rute Fialho. Avenida Marquês de Pombal, 22-B 2700-571 Amadora PORTUGAL Tel.: (+351) 214 989 400 Telm.: (+351) 965 912 370 · (+351) 910 510 304 Fax: (+351) 214 989 401 Endereço eletrónico: [email protected] Título: The One Who Knocks: The Hero as Villain in Contemporary Televised Narratives Autor: Maria João Brasão Marques Série: Ensaio ISBN: 978-972-9370-27-4 Citações do texto: MARQUES, Maria João Brasão (2016), The one who knocks: the hero as villain in contemporary televised narratives, Amadora, ESTC Edições, disponível em <www.estc.ipl.pt>. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License. https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/CC_Affiliate_Network O conteúdo desta obra está protegido por Lei. -

Clifford the Big Red Dog Goes on Tour! MAY 2018 See Page 31 for Details

Clifford The Big Red Dog goes on tour! MAY 2018 See page 31 for details NOVA Wonders Airs 8pm Wednesdays Journey to the frontiers of science, where researchers are tackling some of the biggest questions about life and the cosmos in this six-part mini-series. See story, p. 2 MONTANAPBS PROGRAM GUIDE MontanaPBS Guide On the Cover MAY 2018 · VOL. 31 · NO. 11 COPYRIGHT © 2018 MONTANAPBS, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED MEMBERSHIP 1-866-832-0829 SHOP 1-800-406-6383 EMAIL [email protected] WEBSITE www.montanapbs.org ONLINE VIDEO PLAYER watch.montanapbs.org The Guide to MontanaPBS is printed monthly by the Bozeman Daily Chronicle for MontanaPBS and the Friends of MontanaPBS, Inc., a nonprofit corporation (501(c)3) P.O. Box 10715, Bozeman, MT 59719-0715. The publication is sent to contributors to MontanaPBS. Basic annual membership is $35. Nonprofit periodical postage paid at Bozeman, MT. PLEASE SEND CHANGE OF ADDRESS INFORMATION TO: SHUTTERSTOCK OF COURTESY MontanaPBS Membership, P.O. Box 173345, Bozeman, MT 59717 KUSM-TV Channel Guide P.O. Box 173340 · Montana State University Mont. Capitol Coverage Bozeman, MT 59717–3340 MontanaPBS World OFFICE (406) 994-3437 FAX (406) 994-6545 MontanaPBS Create E-MAIL [email protected] MontanaPBS Kids BOZEMAN STAFF MontanaPBS HD INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER Aaron Pruitt INTERIM DIRECTOR OF CONTENT/ Billings 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 CHIEF OPERATOR Paul Heitt-Rennie Butte/Bozeman 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 SENIOR DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Crystal Beaty MEMBERSHIP/EVENTS MANAGER Erika Matsuda Great Falls 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 DEVELOPMENT ASST. -

Yoko Ono Albumi Lista (Diskografia & Aikajana)

Yoko Ono Albumi Lista (Diskografia & Aikajana) https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/unfinished-music-no.-1%3A-two-virgins- Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins 777742/songs Wedding Album https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/wedding-album-631765/songs Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/unfinished-music-no.-2%3A-life-with-the-lions- Lions 976426/songs Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/yoko-ono%2Fplastic-ono-band-507672/songs Season of Glass https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/season-of-glass-3476814/songs Feeling the Space https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/feeling-the-space-3067999/songs Approximately Infinite Universe https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/approximately-infinite-universe-1749449/songs Fly https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fly-616152/songs Take Me to the Land of Hell https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/take-me-to-the-land-of-hell-15131565/songs Between My Head and the Sky https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/between-my-head-and-the-sky-4899102/songs Starpeace https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/starpeace-7602195/songs https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/it%27s-alright-%28i-see-rainbows%29- It's Alright (I See Rainbows) 3155778/songs A Story https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/a-story-2819918/songs Rising https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/rising-7336112/songs Yokokimthurston https://fi.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/yokokimthurston-8054655/songs Walking on Thin -

Negrocity: an Interview with Greg Tate

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2012 Negrocity: An Interview with Greg Tate Camille Goodison CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/731 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] NEGROCITY An Interview with Greg Tate* by Camille Goodison As a cultural critic and founder of Burnt Sugar The Arkestra Chamber, Greg Tate has published his writings on art and culture in the New York Times, Village Voice, Rolling Stone, and Jazz Times. All Ya Needs That Negrocity is Burnt Sugar's twelfth album since their debut in 1999. Tate shared his thoughts on jazz, afro-futurism, and James Brown. GOODISON: Tell me about your life before you came to New York. TATE: I was born in Dayton, Ohio, and we moved to DC when I was about twelve, so that would have been about 1971, 1972, and that was about the same time I really got interested in music, collecting music, really interested in collecting jazz and rock, and reading music criticism too. It kinda all happened at the same time. I had a subscription to Rolling Stone. I was really into Miles Davis. He was like my god in the 1970s. Miles, George Clinton, Sun Ra, and locally we had a serious kind of band scene going on. -

The Hero As Villain in Contemporary Televised Narratives

THE ONE WHO KNOCKS: THE HERO AS VILLAIN IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISED NARRATIVES Maria João Brasão Marques Dissertação de Mestrado em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos Março de 2016 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas – Estudos Ingleses e Norte-Americanos realizada sob a orientação científica da Professora Doutora Isabel Oliveira Martins. Show me a hero and I will write you a tragedy. F. Scott Fitzgerald AGRADECIMENTOS À minha orientadora, a Professora Doutora Isabel Oliveira Martins, pela confiança e pelo carinho nesta jornada e fora dela, por me fazer amar e odiar os Estados Unidos da América em igual medida (promessa feita no primeiro ano da faculdade), por me ensinar a ser cúmplice de Twain, Fitzgerald, Melville, McCarthy, Whitman, Carver, tantos outros. Agradeço principalmente a sua generosidade maior e uma paixão que contagia. Às Professoras Iolanda Ramos e Teresa Botelho, por encorajarem o meu investimento académico e por me facultarem materiais indispensáveis nesta dissertação, ao mesmo tempo que contribuíram para o meu gosto pela cultura inglesa e norte-americana. À professora Júlia Cardoso, por acreditar nesta demanda comigo e me fazer persistir até chegar a bom porto. Ao Professor João Maria Mendes, para sempre responsável pela minha paixão pelas narrativas, pelos heróis, pelo prazer de contar histórias que se mostram, pelo gosto de construir personagens que falham constantemente e que constantemente se reerguem. Aos meus pais, por me deixarem continuar a estudar. THE ONE WHO KNOCKS: THE HERO AS VILLAIN IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISED NARRATIVES MARIA JOÃO BRASÃO MARQUES RESUMO PALAVRAS-CHAVE: herói, anti-herói, protagonista, storytelling televisivo, revolução criativa, paradigma do herói, vilão. -

David Liebman Papers and Sound Recordings BCA-041 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Axel

David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Axel This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 30, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee Archives Berklee College of Music 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 David Liebman papers and sound recordings BCA-041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Scores and Charts................................................................................................................................... -

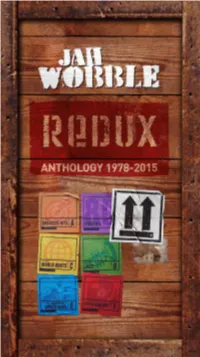

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past.