Barriers to Active Transport in Palmerston North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Region (Total Allocation) Cluster

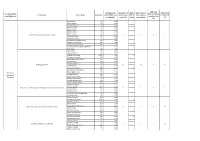

Additional Contribution to Base LSC FTTE Whole Remaining FTTE Total LSC for Education Region Resource (Travel Cluster Name School Name School Roll cluster FTTE based generated by FTTE by to be allocated the Cluster (A (Total Allocation) Time/Rural etc) on school roll cluster (A) school across cluster + B) (B) Avon School 64 0.13 Eltham School 150 0.30 Huiakama School 14 0.03 Makahu School 14 0.03 Marco School 17 0.03 Midhirst School 114 0.23 Ngaere School 148 0.30 Central Taranaki Community of Learning 4 3 0 4 Pembroke School 95 0.19 Rawhitiroa School 41 0.08 St Joseph's School (Stratford) 215 0.43 Stratford High School 495 0.99 1 Stratford Primary School 416 0.83 Taranaki Diocesan School (Stratford) 112 0.22 Toko School 129 0.26 Apiti School 30 0.06 Colyton School 103 0.21 Feilding High School 1,514 3.03 3 Feilding Intermediate 338 0.68 Halcombe Primary School 177 0.35 Hiwinui School 148 0.30 Kimbolton School 64 0.13 Feilding Kāhui Ako 8 4 0 8 Kiwitea School 67 0.13 Lytton Street School 563 1.13 1 Manchester Street School 383 0.77 Mount Biggs School 78 0.16 Taranaki/ Newbury School 155 0.31 Whanganui/ North Street School 258 0.52 Manawatu Waituna West School 57 0.11 Egmont Village School 150 0.30 Inglewood High School 383 0.77 Inglewood School 325 0.65 Kaimata School 107 0.21 Kāhui Ako o te Kōhanga Moa – Inglewood Community of Learning 2 2 0 2 Norfolk School 143 0.29 Ratapiko School 22 0.04 St Patrick's School (Inglewood) 81 0.16 Waitoriki School 29 0.06 Ashhurst School 432 0.86 Freyberg High School 1,116 2.23 2 Hokowhitu School 379 -

Decision No. C/&/99 in the MATTER of the Resource Management Act

Decision No. C/&/99 IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER of an appeal under s120 of the Act BETWEEN COLIN PETER STOKES RMA: 532/98 Appellant AND THE CHRISTCHURCH CITY COUNCIL Respondent AND NIMBUS HOLDINGS LIMITED Applicant BEFORE THE ENVIRONMENT COURT Environment Judge J R Jackson Environment Commissioner R S Tasker Environment Commissioner R Grigg HEARING at CHRISTCHURCH on 30 November, 1 and 4 December 1998 (Final submissions received 11 December 1998) APPEARANCES Mr C P Stokes for himself Ms P Steven and Ms S J Weston for Nimbus Holdings Limited Ms C E Robinson for the Christchurch City Council Mr R A Sedgley for himself as a section 271A party Mr W J de Hart for Mrs S Genet as a section 271 A party 2 DECISION INDEX [A] Background [B] Preliminary Legal Issues [C] The Evidence [D] Matters to be considered (section 104) [E] The Threshold Tests (Section 105(2A)) [F] Assessment under section 105(1) [G] Outcomes [A] Background 1. On 11 February 1998 Nimbus Holdings Limited (“Nimbus”) applied to the Christchurch City Council (“the Council”) for a land use consent under the Resource Management Act 1991 (“the Act” or “the RMA”) to establish and operate a motel, including a managers residence, at 140 Main North Road, Christchurch (“the proposal”). The site is located on the corner of Main North Road and Meadow Street Christchurch, and is 1047m2 in area. 2. Meadow Street is a no exit street with a motor camp at the closed end. Most of Meadow Street is residential except for a panel beating shop directly opposite the site. -

Youth Directory

YOUTH DIRECTORY The Youth Directory was originally produced by the Youth One Stop Shop (‘YOSS’) in 1995. It is not a complete listing of all the agencies and organisations that work with young people in Palmerston North – but a list of community groups that we use as referral sources. On request from community groups YOSS in co-operation with START, have made this information available and it is important that it is used as a living document, needing amendments and additions. Please feel free to photocopy and hand the Youth Directory on to friends and colleagues. Please contact us with any amendments or additions that can be made in subsequent editions of the Youth Directory. Corner Andrew Young & Cuba Streets PO Box 2074, Palmerston North (06) 355 5143 [email protected] This directory was updated on 30 September 2011. CONTENTS Manawatu Lesbian and Gay Rights Association 24 Hour Help .................................5 (MALGRA) ......................................................... 13 MASH Trust ....................................................... 13 Alcoholics Anonymous .......................................... 5 MUSA Advocacy Service ...................................... 13 Al’Anon ............................................................... 5 Netsafe – The Internet Safety Group.................... 13 ARCS Manawatu Abuse and Rape Crisis Support ..... 5 New Zealand Federation of Disability Information City Doctors ........................................................ 5 Centre’s............................................................ -

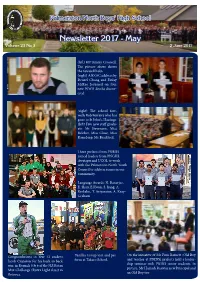

Newsletter 2017 - May Volume 23 No 3 2 June 2017

Palmerston North Boys’ High School Newsletter 2017 - May Volume 23 No 3 2 June 2017 (left) RIP Jimmy Croswell. The picture above shows the farewell haka (right) ANZAC address by Denzel Chung and Finlay McRae focussed on four new WWII deaths discov- ered. (right) The school fare- wells Rob Ferreira who has gone to St John’s, Hastings (left) Five new staff gradu- ate: Mr Stevenson, Miss Belcher, Miss Close, Miss Kaandorp, Mr Braddock. Three prefects from PNBHS joined leaders from PNGHS, Awatapu and UCOL to work with the Palmerston North Youth Council to address issues in our community. Language Awards: N. Banerjee, E. Shaji, E.Kwon, S. Jiang, A. Berkahn, T. Ariyaratne, A. Keay- Graham On the initiative of Mr Finn Barnett (Old Boy Congratulations to Year 12 student Pasifika Group visit and per- and teacher at PNINS) prefects held a leader- Jacob Cranston for his back to back form at Takaro School. ship seminar with PNINS senior students. In win in Rounds 5 & 6 of the NZ Rotax picture, Mr Hamish Ruawai, new Principal and Max Challenge (Rotax Light class) in page 1 an Old Boy too Rotorua. We saw it when one of our young men stood up for a stranger who From the Rector was being verbally abused and confronted physically, by a group of Mr David Bovey young people, while trying to do his job – and our young man stood in front of the group and told them to leave. That young man made the right decision and showed real courage. Dear Parents The new term began in the worst possible way with the news that Mr Crosswell had passed away in the last week of the school holidays. -

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Manawatu Region AED Home Fields Location/Nearest AED St Matthews Collegiate Y St Matthews Collegiate St

Manawatu Region AED Home Fields Location/Nearest AED St Matthews Collegiate Y St Matthews Collegiate St. Matthew's Collegiate School - Located in the main reception of Main House (Boarding Hostel) Hokowhitu AFC Y Hokowhitu Park Hokowhitu Bowling Club, white box in a doorway on the outside of the building. Massey FC Y Massey University Rec centre desk and security van Wairarapa College Y Wairarapa College Wairarapa College Hostel which is adjacent to all the school sports fields Longburn Adventist College Y Longburn Adventist College Lonburn Adventist College - Secure Cabinet - Outside Main Reception Nga Tawa Diocesan Y Nga Tawa Diocesan A the school, in the main block in pigeon hole area staff mailings, and then on countdown wall Horowhenua College Y Horowhenua College Horowhenua College main office St Peters College Y St Peters College St Peter's College - Sick Bay PNGHS Y Hokowhitu Park Hokowhitu Bowling Club, white box in a doorway on the outside of the building. Awatapu College Y Awatapu College Awatapu College - Administration Building - Main Office Feilding High School Y Feilding High School Feilding High School Pahiatua FC Y Bush Park Multisports Complex Bush Multisports Complex on Huxley St, Pahiatua Huntley School Y Huntley School Huntley School - Staff Room Tararua College N Tararua College Bush Multisports Complex on Huxley St, Pahiatua Palmerston North Marist N Skoglund Park Freyberg Community Pool Takaro FC N Monrad Bowling club at Takaro club rooms, Z Pioneer Highway for Monrad park Freyberg High School N Freyberg High School -

Western Bay of Plenty District Council Council Chief Executive Officers

347 Local Government Members (2019/20) Determination Schedule 2 2019 Te Awamutu Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 18,132 Member 9,006 Wairoa District Council Office Annual remuneration ($) Mayor 101,000 Councillor (Minimum Allowable Remuneration) 23,961 Waitaki District Council Annual remuneration Office ($) Mayor 114,500 Councillor (Minimum Allowable Remuneration) 24,125 Ahuriri Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 11,639 Member 5,820 Waihemo Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 12,087 Member 6,044 Waitomo District Council Office Annual remuneration ($) Mayor 97,500 Councillor (Minimum Allowable Remuneration) 23,731 Wellington City Council Office Annual remuneration ($) Mayor 180,500 Councillor (Minimum Allowable Remuneration) 86,874 Makara-Ohariu Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 9,429 Member 4,716 Tawa Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 18,810 66 348 Local Government Members (2019/20) Determination 2019 Schedule 2 Office Annual remuneration ($) Member 9,405 Western Bay of Plenty District Council Office Annual remuneration ($) Mayor 136,500 Councillor (Minimum Allowable Remuneration) 32,959 Katikati Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 11,008 Member 5,504 Maketu Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 5,827 Member 2,914 Omokoroa Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 7,987 Member 3,993 Te Puke Community Board Office Annual remuneration ($) Chairperson 11,008 -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

Waipa District Council

HAMILTON CITY DEVELOPMENT MANUAL Volume 5 District Council Supplement Version : September 2010 Volume 5 District Council Supplement Table of Contents Part 1 : General Part 2 : Earthworks and Land Stability (no additions) Part 3 : Road Works Standard Drawings DCS301 Rural Entranceways – Residential, Light & Heavy Commercial (except for Waikato District Council – refer separate WDC Addendum) DCS302 Rural Vehicle Accessway Separation Diagram Part 4 : Stormwater Drainage Part 5 : Wastewater Drainage Standard Drawings DCS501 Internal Drop Manholes Part 6 : Water Supply Standard Drawings DCS601 Typical Valve Marker Plate DCS602 Typical Water Meter Marker DCS603 District Connection Installation DCS604 Typical Network Layout Part 7 : Street Landscaping (no additions) Part 8 : Network Utilities (no additions) Part 9 : District Council Addendums as follows: 1. Waikato District Council Version : September 2010 Hamilton City Development Manual Volume 5 : District Council Supplement Part 1 – General Authorised by : N/A Page 1 of 23 PART Infrastructure Manual Design 3 PART 1 - GENERAL – STREET WORKS 1.0 This volume has been prepared as a supplement to the Hamilton City Development Manual which has been adopted for use by the following neighbouring district councils: Waikato – Waipa Otorohanga Guide : Design 2 Volume Waitomo 2.0 The volume sets out general variances to the existing Manual and/or additional design standards or technical specifications that should be followed for the installation of services in subdivision and contract works in the above district council areas. Each district council may also maintain an addendum to this Manual setting out specific district requirements, and each district reserves the right to make a final decision regarding any of these standards to suit the individual practices within their district. -

Original Council Agenda

DOC ID AUG16ODC Otorohanga District Council AGENDA 16 August 2016 10.00am Members of the Otorohanga District Council Mr MM Baxter (Mayor) Mr RM Johnson Mrs RA Klos Mr KM Philllips Mrs DM Pilkington (Deputy Mayor) Mr R Prescott Mr PD Tindle Mrs AJ Williams Meeting Secretary: Mr CA Tutty (Governance Supervisor) DOC ID AUG16ODC OTOROHANGA DISTRICT COUNCIL 16 August 2016 Notice is hereby given that an Ordinarymeeting of the Otorohanga District Council will be held in the Council Chambers, Maniapoto Street, Otorohanga on 16 August 2016 commencing at 10am. 8 August 2016 DC Clibbery CHIEF EXECUTIVE AGENDA ORDER OF BUSINESS: ITEM PRECIS PAGE PRESENT 1 IN ATTENDANCE 1 APOLOGIES 1 OPENING PRAYER 1 ITEMS TO BE CONSIDERED IN GENERAL BUSINESS 1 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES – 19 JULY 2016 1 DECLARATION OF INTEREST 1 REPORTS ITEM 328 ROUTINE ENGINEERING REPORTS 1 ITEM 329 APPLICATION FOR TEMPORARY ROAD CLOSURE – HAMILTON CAR 8 CLUB – CLUBMAN RALLY ITEM 330 HEALTH & SAFETY REPORT 10 ITEM 331 REVIEW OF GAMBLING VENUE POLICIES 13 ITEM 332 MINUTES OF RAUKAWA CHARATABLE TRUST AND THE JOIN 18 MANAGEMENT AGREEMENT COUNCILS GOVERNANCE FORUM ITEM 333 ODC MATTERS REFERRED FROM 19 JULY 2016 25 GENERAL 25 Otorohanga District Council - AGENDA – Date/Month/Year Page 0 PRESENT IN ATTENDANCE APOLOGIES ITEMS TO BE CONSIDERED IN GENERAL BUSINESS DECLARATION OF INTEREST CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES – 19 JULY 2016 REPORTS ITEM 328 ROUTINE ENGINEERING REPORT – MAY - JULY 2016 To: His Worship the Mayor & Councillors Otorohanga District Council From: Engineering Manager Date: 16 August 2016 Relevant Community Outcomes The Otorohanga District is a safe place to live Ensure services and facilities meet the needs of the Community Executive Summary This is a routine report on engineering matters for the period May to July 2016. -

Manawatu Inter-Secondary School Athletics 2016 CONTENTS

FREYBERG HIGH SCHOOL AND SPORT MANAWATU PRESENT Manawatu Inter-Secondary School Athletics 2016 CONTENTS Page 3 - Host School Welcome Page 4 - Programme Oath of Fairplay Page 5 - MISSA Officials EVENT HISTORY Page 6 - Meeting Officials Manawatu Inter-Secondary Page 9 - Meeting Rules School Athletics (MISSA) is the Secondary School’s oldest Page 12 - Competing Schools event, with the inter-school records dating back to 1961. Page 13 - Specifications Each local school takes a Page 14 - Events programme turn at hosting the event, held at the Massey University Page 18 - Records Community Athletics Track. 16 schools from around Page 20 - Cross Country the region come together Page 21 - Site Map annually to compete, and celebrate the local athletics Page 22 - Acknowledgements talent here in the Manawatu. Visit sportmanawatu.org.nz for more information! 2 Welcome From Host School Freyberg High School is delighted to be hosting the Manawatu Inter-Secondary School Athletics meeting for 2016. We are well aware that we are only able to make this event successful through the support of the Palmerston North Athletics and Harrier Club and Massey University. We particularly appreciate the time that Athletic Club volunteers have given to this event over a number of years and their advice and participation at the meeting is greatly appreciated. The event management team at Freyberg: Linda Smith, Rosemary Barsanti, Saskia Beveridge, Vivienne Hill, Jamie Mills and George McConachy have put in a huge effort to ensure this event is a success for all the athletes and officials involved and I am very grateful for their time. Finally, I wish to thank all the staff from Freyberg High School who given up their Saturday to support all those athletes who have worked hard so that they can do their best on this day. -

Manawatu Inter-Secondary School Cross Country 2019

Manawatu Inter-Secondary School Cross Country 2019 Athletes with Disabilities School 1 James Ironside Feilding High School 12m 46s 2 Kieran Trask Feilding High School 3 Wycliff Finaulahi Feilding High School 4 Ron Watkins Feilding High School 5 Jamie Davidson Tararua College 6 Cayden Adkins Feilding High School Junior Boys School Team Results 1 Reuben Duker Palmerston North Boys' High School 15m 0.55s Record Palmerston North Boys' High School 1st 2 Thomas Duncan Palmerston North Boys' High School Feilding High School 2nd 3 Jonathon Jamieson Palmerston North Boys' High School Dannevirke High School 3rd 4 Cameron Walker Dannevirke High School 5 Fergus Doolan Palmerston North Boys' High School 6 Tyler Hodson St Peter's College 7 Mitchell Hodgetts Feilding High School 8 Griffyn Kapao Palmerston North Boys' High School 9 Max O'Connor Palmerston North Boys' High School 10 Lucas Reed Palmerston North Boys' High School Junior Girls School Team Results 1 Kimberley Walsh St Peter's College 17m 3.19s Record Palmerston North Girls' High School 1st 2 Georgie Furnell Palmerston North Girls' High School Feilding High School 2nd 3 Lucy Evans Feilding High School St Peter's College 3rd 4 Monique Gorrie Palmerston North Girls' High School 5 Holly Bird Feilding High School 6 Kylah Gunn Palmerston North Girls' High School 7 Annie Airey Nga Tawa 8 Jayde Rolfe St Peter's College 9 Rebekah Trewhitt St Peter's College 10 Olivia Clifton Nga Tawa Intermediate Boys School Team Results 1 Liam Wall Palmerston North Boys' High School Palmerston North Boys' High School