A Comparison of Telemental Health Terminology Used Across Mental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LISA KUDROW Biography Emmy Award-Winning Actress Lisa Kudrow

LISA KUDROW Biography Emmy Award-winning actress Lisa Kudrow continues to bring her original sense of comedic timing and delivery to every role she takes on. Most recently audiences saw Lisa in the DreamWorks film Hotel for Dogs. Prior that she starred in P.S. I Love You with Hilary Swank and Gerard Butler and in the independent film Kabluey which premiered at the Los Angeles Film Festival and at the Hamptons Film Festival. Her upcoming projects include the recently completed independent films Paper Man opposite Jeff Daniels, 17 Photos of Isabel with Natalie Portman for director Don Roos, Powder Blue with Forrest Whitaker and Ray Liotta and Bandslam for writer/director Todd Graff. Lisa has received rave reviews for her previous feature film roles. She won the Best Supporting Actress Award from the New York Film Critics, an Independent Spirit Award nomination and a Chicago Film Critics Award nomination for her role in the Don Roos scripted and directed film The Opposite of Sex (1998). She won a Blockbuster Award and received a nomination for an American Comedy Award for her starring role opposite Billy Crystal and Robert DeNiro in the Warner Bros. boxoffice hit Analyze This (1999) for director Harold Ramis. Lisa’s additional film credits include starring roles in Happy Endings (2005) for writer/director Don Roos which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival; Wonderland (2004) with Val Kilmer, in which she portrayed Sharon Holmes, wife of porn star John Holmes, in the film based on the infamous Wonderland Avenue murders; the Warner Bros. film Analyze That (2002), the sequel to Analyze This (1999), the Columbia Pictures film Hanging Up (2000) opposite Meg Ryan and Diane Keaton, Paramount’s Lucky Numbers (2000) with John Travolta, in the critically acclaimed hit comedy Romy & Michele’s High School Reunion (1997) with Mira Sorvino, Clockwatchers (1997) in which she starred opposite Toni Collette and Parker Posey and the Albert Brooks’ comedy Mother (1996). -

Recurrent and Residual Aneurysms After Woven Endobridge (WEB) Therapy: What’S Next?

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.14404 Recurrent and Residual Aneurysms After Woven EndoBridge (WEB) Therapy: What’s Next? Catherine Peterson 1 , Branden J. Cord 1 1. Neurological Surgery, University of California Davis, Sacramento, USA Corresponding author: Catherine Peterson, [email protected] Abstract The prevalence of recurrent and residual aneurysms following Woven EndoBridge (WEB) treatment is not insignificant. The goal of this systematic review was to evaluate retreatment methods for such aneurysms and their outcomes. PubMed, Embase, and Scopus databases were systematically searched, and results were reported according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. Original studies reporting on aneurysms that were retreated after WEB were included. Sixteen studies (n = 901 aneurysms), of which three were prospective, reported on retreated aneurysms following initial WEB treatment. Of those 901 aneurysms, on average 18.7 ± 11.5% were recurrent or residual at the last follow-up and 10.7 ± 11% required some form of retreatment. When compared to WEB-IT (WEB Intra- saccular Therapy) data, retreated aneurysms were more likely to be large in size (p < 0.0001) and more likely to have been initially treated with the WEB dual-layer configuration. The mean age of those with retreated aneurysms was 58 ± 5.7 years old, and the mean size of aneurysm dome was 11.1 ± 5.5 millimeters. Majority (34.1%) of the aneurysms were located at the basilar apex. Retreatment modalities included coiling (20%), stent-assisted coiling (38.7%), additional WEB device (13.3%), flow diversion (16%), and clipping (12%). Majority of retreated cases had favorable outcomes, with 96.4 ± 13.4% of the cases demonstrating technical success and 90.5 ± 18.2% having adequate occlusion at the last follow-up. -

Using Technology Creatively to Empower Diverse Populations in Counseling

VISTAS Online VISTAS Online is an innovative publication produced for the American Counseling Association by Dr. Garry R. Walz and Dr. Jeanne C. Bleuer of Counseling Outfitters, LLC. Its purpose is to provide a means of capturing the ideas, information and experiences generated by the annual ACA Conference and selected ACA Division Conferences. Papers on a program or practice that has been validated through research or experience may also be submitted. This digital collection of peer-reviewed articles is authored by counselors, for counselors. VISTAS Online contains the full text of over 500 proprietary counseling articles published from 2004 to present. VISTAS articles and ACA Digests are located in the ACA Online Library. To access the ACA Online Library, go to http://www.counseling.org/ and scroll down to the LIBRARY tab on the left of the homepage. n Under the Start Your Search Now box, you may search by author, title and key words. n The ACA Online Library is a member’s only benefit. You can join today via the web: counseling.org and via the phone: 800-347-6647 x222. Vistas™ is commissioned by and is property of the American Counseling Association, 5999 Stevenson Avenue, Alexandria, VA 22304. No part of Vistas™ may be reproduced without express permission of the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved. Join ACA at: http://www.counseling.org/ Suggested APA style reference information can be found at http://www.counseling.org/library/ Article 14 Using Technology Creatively to Empower Diverse Populations in Counseling Renae Reljic, Amney Harper, and Hugh Crethar Reljic, Renae, Ph.D. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/7/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

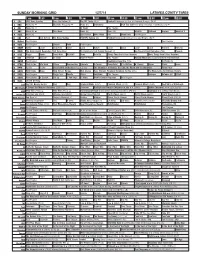

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/7/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Cincinnati Bengals. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Swimming PGA Tour Golf Hero World Challenge, Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Wildlife Outback Explore World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Indianapolis Colts at Cleveland Browns. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR The Omni Health Revolution With Tana Amen Dr. Fuhrman’s End Dieting Forever! Å Joy Bauer’s Food Remedies (TVG) Deepak 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Holiday Heist (2011) Lacey Chabert, Rick Malambri. 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Beverly Hills Chihuahua 2 (2011) (G) The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe Fútbol MLS 50 KOCE Wild Kratts Maya Rick Steves’ Europe Rick Steves Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) The Roosevelts: An Intimate History 52 KVEA Paid Program Raggs New. -

Hitting the Brakes on Bicycle Lanes

WWW.ALEXTIMES.COM JANUARY 30, 2014 | 1 Vol. 10, No. 5 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper JANUARY 30, 2014 Hitting the brakes on bicycle lanes IMAGE/CITY OF ALEXANDRIA Concerns remain about the final design of Carr City Centers’ 120-room boutique hotel, but city council- ors unanimously approved the project Saturday. The board of architectural review also must sign off on it before construction can begin. What a Full steam ahead depressing PHOTO/ERICH WAGNER Officials sign off on marks the first major project early end to A cyclist navigates the portion of King Street that’s slated to have bike outlined in the riverside plan lanes installed on a chilly winter morning. The addition of dedicated waterfront hotel project our aspirations lanes has neighbors up in arms, and city officials are taking another to earn city council’s blessing. look at the project following the outcry. BY DERRICK PERKINS And that has drawn scrutiny for a world-class from several local officials waterfront.” City council will project last month. Residents remain appre- and residents, who want the But after outcry from resi- review controversial hensive about a waterfront undertaking delayed because - Bob Wood dents, local officials said they they believe it sets the stan- King Street project hotel in the 200 block of S. Former member of would bring the proposal — Union St., but city councilors dard for future waterfront re- the waterfront which would install bike lanes BY ERICH WAGNER green-lighted the project with development. plan work group between Russell Road and Jan- a 6-0 vote Saturday. -

A Comprehensive Review and a Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Internet-Based Psychotherapeutic Interventions

A Comprehensive Review and a Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Internet-Based Psychotherapeutic Interventions Azy Barak Liat Hen Meyran Boniel-Nissim Na’ama Shapira ABSTRACT. Internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions have been used for more than a decade, but no comprehensive review and no extensive meta-analysis of their effectiveness have been con- ducted. We have collected all of the empirical articles published up to March 2006 (n ¼ 64) that examine the effectiveness of online ther- apy of different forms and performed a meta-analysis of all the stu- dies reported in them (n ¼ 92). These studies involved a total of 9,764 clients who were treated through various Internet-based psychological interventions for a variety of problems, whose effec- tiveness was assessed by different types of measures. The overall mean weighted effect size was found to be 0.53 (medium effect), which is quite similar to the average effect size of traditional, face- to-face therapy. Next, we examined interacting effects of various Azy Barak, Liat Hen, Meyran Boniel-Nissim, and Na’ama Shapira, Faculty of Education, University of Haifa, Aba Hushi Rd., Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel. We are indebted to Ronnen Fluss for his assistance in analyzing the data. Address correspondence to Azy Barak, Faculty of Education, University of Haifa, Aba Hushi Rd., Mount Carmel, Haifa 31905, Israel. E-mail: [email protected]. Journal of Technology in Human Services, Vol. 26(2/4) 2008 Available online at http://jths.haworthpress.com # 2008 by The Haworth Press. All rights reserved. doi: 10.1080/15228830802094429 109 110 JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY IN HUMAN SERVICES possible relevant moderators of the effects of online therapy, includ- ing type of therapy (self-help web-based therapy versus online com- munication-based etherapy), type of outcome measure, time of measurement of outcome (post-therapy or follow-up), type of prob- lem treated, therapeutic approach, and communication modality, among others. -

Web Therapy for Internet Addicts: a Case Study of Self-Healing by Social Media Addicts in Indonesia

Web Therapy for Internet Addicts: A Case Study of Self-Healing by Social Media Addicts in Indonesia *Nuning Kurniasih Department of Library and Information Science, Faculty of Communication Science, Universitas Padjadjaran e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] Julian Amriwijaya Department of General and Experimental Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Padjadjaran e-mail: [email protected] Proceedings 2nd International Conference on Record and Library Organized by Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya. Hotel Ibis, Surabaya, 12-13 Oktober 2016 Pages: 74-76 ABSTRACT This study aims to analyze how the internet sources used as therapy treatment (Web Therapy) by internet addicts, especially social media addicts. The method used is qualitative method based on case study perspective. The method used to collect data incorporates in-depth interview, observation, and literature study. The informants are nine internet addicts who acknowledge themselves as internet addicts, especially social media addicts not by medical diagnostic as one, and been using internet sources as a treatment to overcome their mental issue. Triangulation is conducted by interviewing a psychology expert. The study results show that (1) The informants admit that internet sources help them reduce stress while under pressure. (2) The informants admitted the initiative comes within themselves to use internet sources in order to reduce stress. (3) There are some ways for informants to identify their personal problems, that is (a) When they feel like they have no one around to talk with, to share their problems with, they use chatting platform to talk with and positive feedbacks from social media. (b) When they encounter negative psychological condition, they need entertainment from internet sources to be relaxed and refresh. -

State of Automotive Content Marketing

State of Automotive Content Marketing Mapping the Road to Success in 2015 Copyright © 2014 Contently. All rights reserved. Contently.com By Natalie Burg You can’t build a reputation on what you are going to do. — Henry Ford THE STATE OF AUTOMOTIVE CONTENT MARKETING: MAPPING THE ROAD TO SUCCESS IN 2015 Editor’s Note As someone who has spent approximately 43 percent of his life watching televised sports, I’m no stranger to auto ads. But while the image of manly men hauling dusty boul- ders in shiny trucks will live with me forever, marketing in the auto industry has evolved far beyond that. In fact, it might now be more familiar to those who grew up on 90’s sitcoms. Acura has scored an incredible win by sponsoring Jerry Seinfeld’s “Comedians in Cars Getting Cof- fee,” while Lexus has been featuring Lisa Kudrow’s award-winning “Web Therapy” on its web-series channel, L Studio, for four years running. In an industry where the sales cycle has lengthened to six years, auto companies are embracing the power of content to build relationships over time. In this ebook, we look at the major trends moving the industry forward, as well as the speed bumps that are getting in auto content marketers’ way. We hope you enjoy, and if you have any questions or comments, you can find me@JoeLazauskas or via email at [email protected]. — Joe Lazauskas Contently Editor in Chief 3 CONTENTLY THE STATE OF AUTOMOTIVE CONTENT MARKETING: MAPPING THE ROAD TO SUCCESS IN 2015 Table of Contents I. -

Local Officials: Scott Did Right Thing Monday to Pull Standards

1 TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM ABANDONS NATIONAL TESTING REGIMEN Local officials: Scott did right thing Monday to pull Standards. state’s dismissal City. “That’s why the Governor Common Core State Florida out of Scott — caught in a crossfire of PARCC. should be applauded for setting a Standards may also the Partnership over the future of Florida’s public “Florida’s had path forward to determine what’s be revised, Gov. says. for Assessment schools — is trying to respond to incredible suc- best for Florida’s needs. The of Readiness critics of new education standards cess in preparing Governor also took an impor- By AMANDA WILLIAMSON for College and slated to go into effect next year. our children for tant step in informing the U.S. [email protected] Careers test, a Instead of rejecting or endors- the future, and Department of Education that we national assess- ing the standards, Scott called we’re not letting will not subject Florida’s class- Huddleston TALLAHASSEE — Local leg- ment designed Porter for public hearings and possible up in demanding rooms to PARCC. We need to islative and school leaders sup- to measure students’ perfor- changes to the Common Core high standards from classrooms,” port Gov. Rick Scott’s decision mance in Common Core State State Standards in addition to the said Elizabeth Porter, R-Lake PARCC continued on 3A LSHA Citizens Police Academy graduates 24 changes course on taxes Won’t raise millage after all; may revisit issue of 5% raises. -

Jessica Cabot

JESSICA CABOT [email protected] (310) 714-2402 CREATOR OF PROFESSIONALLY PRODUCED CONTENT The Young Hillary Diaries - Lifetime (A&E Networks) May 2015 — November 2016 • Co-created series with director Mandy Fabian, starred as “Young Hillary”, and wrote several episodes • Acted as producer in initial stages, brought on director, writers, and crew. Pitched original pilot to Lifetime. Shitty Boyfriends - Refinery29 (Executive Produced by Lisa Kudrow with New Form Digital) Jan 2014 — Oct 2015 • Created series, wrote original 8 episode outlines, incorporated studio notes, then wrote 6 of 8 produced episodes • Worked closely with Lisa Kudrow throughout process, especially with on-set with punch-ups and revisions. • Participated in development meetings with New Form and Refinery 29 to see project through pre-production to post. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Digital Assettes — Copywriter Vienna (remote) March 2018 — June 2018 • Wrote essays and digital content on personal growth and finances for web-site and social media presence Nick Melvoin for School Board — Regional Field Director Los Angeles, CA March 2017 — May 16th, 2017 • Spoke on behalf of Nick Melvoin in community events and board meetings regarding policy initiatives and platform • Recruited & organized volunteers to strategize canvassing the Venice, Mar Vista, Marina Del Rey, Westchester areas Jill Soloway – Assistant to Writer / Director Los Angeles, CA November 2012 – December 2012 • Assisted with personal daily tasks: errands, organizing calendar and to do list, planning screenings, etc. • Provided creative input on upcoming projects: proofreading, coverage, pitching ideas for punching up scripts. Weeds – Writer’s Assistant Universal City, CA February 2012 – August 2012 • Researched extensive topics pertaining to season, conducting interviews with government lobbyists, fieldwork, etc. -

Web Review Request Therapy User Guide

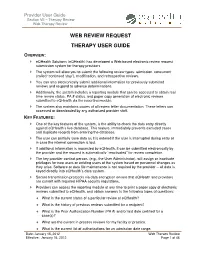

Provider User Guide Section VII – Therapy Review Web Therapy Review WEB REVIEW REQUEST THERAPY USER GUIDE OVERVIEW : eQHealth Solutions (eQHealth) has developed a Web based electronic review request submission system for therapy providers . The system will allow you to submit the following review types: admission, concurrent (called “continued stay”), modification, and retrospective reviews. You can also electronically submit additional information for previously submitted reviews and respond to adverse determinations. Additionally, the system includes a reporting module that can be accessed to obtain real time review status, PA # status, and paper copy generation of electronic reviews submitted to eQHealth via the reporting module. The system also maintains copies of all review letter documentation. These letters c an accessed or downloaded by any authorized provider staff. KEY FEATURES : One of the key features of the system , is the ability to check the data entry directly against eQHealth’s live database . This feature, immediately prevents excluded cases and duplic ate records from entering the database. The user can partially save data as it is entered if the user is interrupted during entry or in case the internet connection is lost. If additional information is requested by eQHealth, it can be submitted electroni cally by the provider and the request is automatically “reactivated” for review completion . The key provider c ontact person, (e.g., the User Administrator), will assign or inactivate privileges for new users or existing users of the system based on personn el changes as they arise. Software or data file maintenance is not required by the provider – all data is keyed directly into eQHealth’s data system. -

The Magazine Celebrating Television's Golden Era of Scripted Programming

Issue #3 January 2016 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming 10 x 60’ DRAMA SERIES SEASON 2 IN PRODUCTION Photo: © Tibo & Anouchka – Capa Drama / Zodiak Fiction / Incendo / Canal + NATPE Stand: 533 Scripted OFC DecJan16.indd 2 04/01/2016 14:40 TBI_FC_VERSAILLES_Zodiak_AD.indd 1 21/12/2015 12:41 A Philosophy Teacher Finds Off-beat Ways to Impact and Change the Lives of his Adolescent Students Contact us at NATPE MIAMI 2016 Find us at Booth 225 www.tv3.cat/sales [email protected] pXX TV3 DecJan16.indd 1 15/12/2015 11:14 In this issue Editor’s Note In the international television business of January 2016, the concept of ‘packaging’, which underpins the American film and TV industries, is not normal procedure. Fast-talking agents and demanding talent representatives exist everywhere, of course, but only in the US do you have that kind of standardised process that links actors, directors and writers to scripts doing the rounds. Now, with US channels keener than ever to work with international partners on high-end drama series, the American agent is branching out from Los Angeles and New York City. Not only that, they see 4 the skill set their regular days jobs have provided – negotiation tactics, rights ownership knowledge, contracting and, crucially, the gift of the gab – as proof that they can sell these packages overseas. In our lead feature on new BBC-AMC spy thriller The Night Manager, William Morris Endeavor’s head of global television, Chris Rice, explains how the famous LA agency became player in international distribution.