Arxiv:Physics/0511254V1 [Physics.Pop-Ph] 30 Nov 2005 Nie Eiwtl Npeaysession Plenary in Talk Review Invited 000-000 2005 Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Smith, Virtual Center, Illinois

I have been involved with the QuarkNet Virtual Center for 8 or 9 years. In that time I have had students display Cosmic Ray research at the Illinois Junior Science and Humanities Symposium and science fairs, through the Masterclass work with data from the Large Hadron Collider, and participate in video conferences with students from Mexico, China, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Japan. A QuarkNet mentor did a video conference with Hispanic students at a school where I formerly worked. My involvement with QuarkNet has provided me with content knowledge I would otherwise not have had, and as a non-physics major I probably would have considered it out of my reach. Thanks to my involvement in QuarkNet I learned of the summer program for teachers at CERN. After participating in that two summers ago, I now have physics teacher friends in more than 30 other countries, and many of us maintain contact through our CERN HST2016 Facebook page. I have also taken six classes of physics students to the Fermilab Open House where they conducted hands-on activities for younger children, followed by tours of Fermilab and Argonne Lab the next day. I would probably not have been invited to be part of that had it not been for my QuarkNet involvement. But because I am a part of QuarkNet, my students are exposed to world-class research facilities as well as feeling they are a part of something far beyond their small town and small science classroom. The photo is from last year's Masterclass; I think the other students were in China and the Philippines, and a third location had temporarily lost the connection. -

Fruit Collider

Fruit Collider https://xkcd.com/1949 LHC and Beyond Standard Model Physics July 22, 2016 1 Fixion https://xkcd.com/1621/ LHC and Beyond Standard Model Physics July 22, 2016 2 QuarkNet Summer Session for Teachers: The Standard Model and Beyond Allie Reinsvold Hall https://quarknet.org/content/quarknet-summer- session-teachers-2020 Summer 2020 LHC and Beyond Standard Model Physics July 22, 2016 3 Course overview What are the fundamental building blocks that make up our universe? Mission: overview of the past, present, and future of particle physics 1. History of the Standard Model, Part 1: Ancient Greeks to Quantum Mechanics 2. History of the Standard Model, Part 2: Particle zoo and the Standard Model 3. Particle physics at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) 4. Beyond the Standard Model at the LHC 5. Neutrino physics 6. Dark matter and cosmology Goal: Bring you to whatever your next level of understanding is and provide resources for when you teach. Not everyone is at the same level and that’s okay. LHC and Beyond Standard Model Physics July 22, 2016 4 Loose ends – questions • What does “color” tell us about a particle? • Color is a quantum number (like spin or electric charge) that tells us how particles interact via the strong force. Can be thought of as “color charge” • Gluons interact with particles that have color charge; photons interact with particles that have EM charge. What about W/Z bosons? • W/Z bosons mediate the weak interaction • Z boson is charged and can also interact electromagnetically • How likely is it that the SM will -

Quarknet: a Unique and Transformative Physics Education Program

education sciences Article QuarkNet: A Unique and Transformative Physics Education Program Marjorie Bardeen 1,*, Mitchell Wayne 2 and M. Jean Young 3 1 Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, IL 60510, USA 2 Department of Physics, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA; [email protected] 3 M. J. Young and Associates, Tucson, AZ 85704, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-630-840-2031 Received: 29 December 2017; Accepted: 15 January 2018; Published: 19 January 2018 Abstract: The QuarkNet Collaboration has forged nontraditional relationships among particle physicists, high school teachers, and their students. QuarkNet centers are located at 50+ universities and labs across the United States and Puerto Rico. We provide professional development for teachers and create opportunities for teachers and students to engage in particle physics data investigations and join research teams. Students develop scientific knowledge and habits of mind by working alongside scientists to make sense of the world using authentic experimental data. Our program is based on a classroom vision where teaching strategies emulate closely the way scientists build knowledge through scientific and engineering practices. Program outcomes show that student engagement in research and masterclasses does develop an understanding of the process of scientific discovery and science. Teachers provide classroom environments that model scientific discovery and science practices and take advantage of opportunities to expand their involvement in the profession of science teaching. We describe success factors that enhance local center programs, and discuss important benefits of the program that flow on to the university faculty. Keywords: professional development; physics; outcomes 1. -

International Masterclasses Hands on Particle Physics

INTERNATIONAL MASTERCLASSES HANDS ON PARTICLE PHYSICS Nantes Swedish Teachers CERN 2.11.2018 Despina Hatzifotiadou 1 A day of immersion in particle physics for 16-18 year old pupils Typical day of International Masterclasses Morning : introductory lectures on • Particle physics (elementary particles, forces, Standard Model and beyond) • Detectors – accelerators – experimental methods Visit of laboratory / experimental site / discussion with scientists and graduate students Lunch – usually offered by the Host Institute Afternoon : students analyse data from an LHC experiment and do a physics measurement They work in groups of 2 per computer; analysis is visual in most cases At the end of the day : Video Conference moderated by two physicists at CERN and connecting up to 5 institutes presentation / merging/ discussion of results, answering questions, quiz Swedish Teachers CERN 2.11.2018 Despina Hatzifotiadou 2 A bit of history and present status 1996: Started in UK 2005: Adopted by EPPOG (European Particle Physics Outreach Group) for all Europe Use data from LEP (the Large Electron Positron collider, CERN, 1989-2000) OPAL Identifying Particles DELPHI Hands on CERN Z0 decays / calculation of branching ratios 2006: U.S. joined program 2010: preparing to move to LHC-based Masterclasses 2011: Start using data from LHC ATLAS W+W- (MINERVA) structure of the proton ATLAS Z0 (HYPATIA) mass, width (+Z' from MC) CMS J/Ψ (in 2011) and W/Z (in 2012) ALICE Looking for strange particles (V0 decays) ALICE Nuclear modification factor LHCB Measurement of -

DH Mcclary and LE Hiller Forward Pixel Detector

QuarkNet Teachers Work on CMS Tracker D. H. McClary and L. E. Hiller University at Buffalo-The State University of New York at Buffalo Silicon Tracker Compact Muon Solenoid for the LHC CMS uses an all-silicon tracker. silicon pixel detectors are situated closest to the beam pipe, while silicon microstrip detectors are used in the outer layers. This versatile tracking system allows charged particle reconstruction with high efficiency and precision. In addition, the silicon pixel detectors bring the capability of identifying tracks from secondary vertices. Such vertices arise from decays of b quarks, and are very useful signatures over a broad spectrum of physics, including the Higgs boson and Supersymmetry searches. The choice of all silicon technology for the tracker should ensure functionality for a 10 year life span in the high radiation environment of LHC. Major LHC Experiments France Geneva Switzerland CMS is one of the two major detectors currently being installed along the LHC or Large Hadron Collider at CERN near Geneva, Switzerland (right). The Compact Muon Solenoid detector is a collaboration of more than 2000 scientists about 40 countries. CMS has three major components (above). The tracker, which is closest to the beam pipe, is used to reconstruct the momentum of the particles created in the 14 TeV proton-proton collisions. Next, the Calorimeters find the energy of the particles produced. The Tracker and Calorimeters are surrounded by a solenoid generating a 4 T magnetic field. Finally, the Muon System aids in identifying muons and measuring their momentum. Searches for the Higgs boson and Supersymmetry form a central part of the CMS physics program. -

Quarknet/Walta/CROP Cosmic Ray Detectors User's Manual

QuarkNet/Walta/CROP Cosmic Ray Detectors User’s Manual Jeff Rylander and Tom Jordan, Fermilab R. J. Wilkes, Hans-Gerd Berns and Richard Gran, U. Washington August 2004 Classroom Cosmic Ray Detector User’s Manual II Classroom Cosmic Ray Detector User’s Manual QuarkNet/Walta/CROP Cosmic Ray Detectors User’s Manual This manual provides information for setting up and using a cosmic ray detector with the QuarkNet Version 2 Data Acquisition (DAQ) board and ancillary hardware. It serves both beginning and advanced users. Much of the technical information was originally compiled in a user’s manual written by R. J. Wilkes. Hans Berns, Rik Gran, Sten Hansen, and Terry Kiper contributed some of the technical documentation with input from the practical experience of many beta testers.1 Although some of the components of your cosmic ray detector may have come from various sources, the heart of the detector is the QuarkNet DAQ board. The development of this board is a collaborative effort involving Fermilab, the University of Nebraska and the University of Washington. Appendix A has a description of the history of this project. Project Development Team Fermilab: Sten Hansen, Tom Jordan, Terry Kiper Univeristy of Nebraska: Dan Claes, Jared Kite, Victoria Mariupolskaya, Greg Snow University of Washington: Hans Berns, Toby Burnett, Paul Edmon, Rik Gran, Ben Laughlin, Jeremy Sandler, Graham Wheel, Jeffrey Wilkes 1 For more technical documentation on the DAQ board, see http://www.phys.washington.edu/~walta/qnet_daq/ i Classroom Cosmic Ray Detector User’s -

The Quarknet CMS Masterclass: Bringing the LHC to Students

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Nuclear and Particle Physics Proceedings 273–275 (2016) 1261–1264 www.elsevier.com/locate/nppp The QuarkNet CMS masterclass: bringing the LHC to students Kenneth Cecire, Thomas McCauley University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556, USA Abstract QuarkNet is an educational program which brings high school teachers and their students into the particle physics research community. The program supports research experiences and professional development workshops and pro- vides inquiry-oriented investigations, some using real experimental data. The CMS experiment at the LHC has released several thousand proton-proton collision events for use in education and outreach. QuarkNet, in collaboration with CMS, has developed a physics masterclass and e-Lab based on this data. A masterclass is a day-long educational workshop where high school students travel to nearby universities and research laboratories. There they learn from LHC physicists about the basics of particle physics and detectors. They then perform a simple measurement using LHC data, and share their results with other students around the world via videoconference. Since 2011 thousands of students from over 25 countries have participated in the CMS masterclass as organized by QuarkNet and the International Particle Physics Outreach Group (IPPOG). We describe here the masterclass exercise: the physics, the online event display and database preparation behind it, the measurement the students undertake, their results and experiences, and future plans for the exercise. Keywords: CMS, masterclass, QuarkNet, IPPOG, LHC, physics education 1. Introduction lider (LHC) at CERN, comprising nearly 3000 physi- cists and around 800 engineers from over 40 coun- QuarkNet [1] is an program that brings high-school tries. -

Looking for Leptons in All the Right Places

L ooking for Lept ons in All the Right P laces by Jennifer Lauren Lee Above: Tania Entwistle’s team of students from Ward Melville High School in New York. Front from left: Stephen Bohlman, Sammi Qin. Back from left: Ram Gupta, Lucas Janson, Ari Richman, Josh Steinberg. Right column: Students around the world participate in videoconferences, lectures, and analysis of particle physics data. Photos: Ken Cecire, Hampton University; Ivan Melo, Žilinská univerzita, Slovakia; and Christine Kourkoumelis, University of Athens, Greece In a typical high school physics textbook, says science- who had to split their event into two half-days, analyzing education specialist Beth Marchant, only the last chapter data one day and conferencing the next morning. is devoted to all the developments since 1900—the stuff Student Stephen Bohlman, from Ward Melville High that physicists are actually working on today. “For School in New York, heard about the EPPOG Masterclass teachers who go by the textbook,” says Marchant, “the program when another teacher—Tania Entwistle, an active class never gets there.” QuarkNet participant—came into his Advanced Placement Marchant is part of a multinational team, from programs (AP) Physics class and asked for volunteers. “It’s stuff that in Europe and the United States, collaborating to trans- interests me,” says Bohlman, 16. “I find it fascinating—all the form the way physics is taught. They offer kids the chance leptons, bosons, hadrons—oh my!” to close their textbooks and experience modern science In the weeks before their conference date, Entwistle’s first-hand. six students used the online preparation guide created A program organized and run by Michael Kobel of the by Kobel, with a downloadable CD-ROM (available in 16 Technical University in Dresden, Germany, gives 16- to languages), to learn how to identify particles based on 18-year-old students the chance to be “physicists for a day,” their “tracks”—the trails left in a particle detector following teaching them to identify subatomic particles from real matter-antimatter collisions. -

The CMS Masterclass and Particle Physics Outreach Kenneth Cecire1a, Marjorie Bardeen2, and Thomas Mccauley1

EPJ Web of Conferences 71, 00027 (2014) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/20147100027 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2014 The CMS Masterclass and Particle Physics Outreach Kenneth Cecire1a, Marjorie Bardeen2, and Thomas McCauley1 1Department of Physics, University of Notre Dame, 225 Nieuwland Science Hall, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 U.S.A 2Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Education Office, MS 226, P.O. Box 500, Batavia, Illinois 60510 U.S.A. Abstract. The CMS Masterclass enables high school students to analyse authentic CMS data. Students can draw conclusions on key ratios and particle masses by combining their analyses. In particular, they can use the ratio of W+ to W- candidates to probe the structure of the proton, they can find the mass of the Z boson, and they can identify additional particles including, tentatively, the Higgs boson. In the United States, masterclasses are part of QuarkNet, a long-term program that enables students and teachers to use cosmic ray and particle physics data for learning with an emphasis on data from CMS. 1 Introduction The CMS Masterclass [1] is one prominent example of the use of authentic particle physics data to bring compelling physics to high schools. CMS, the Compact Muon Solenoid [2], is one of two general-purpose experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Geneva, Switzerland. During International Masterclasses 2013 [3], 50 masterclass institutes in 17 countries offered the CMS Masterclass, roughly ¼ of the total in 2013. To examine the CMS Masterclass, then, is to get some sense of how students look at the data. -

Pavel Nadolsky August 5, 2009

Pavel Nadolsky Department of Physics Southern Methodist University (Dallas, TX) August 5, 2009 Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 1 Awaiting for discoveries of unseen dimensions... Particle physicists sizzle in anticipation of the most important leap in our eld since the discovery of top quark in 1995 Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 2 Awaiting for discoveries of unseen dimensions... 25 years since its commission, the Fermilab Tevatron collider near Chicago (with energy of 1 TeV per each beam) operates at the top of its performance; has an excellent chance to discover or rule out a long-sought Higgs particle predicted by the Standard Model Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 2 Awaiting for discoveries of unseen dimensions... The Large Hadron Collider at CERN is an experiment of superlative scope; gets ready to produce the rst set of data in November at energy 4-5 TeV per beam; will be eventually ramped up to 7 TeV Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 2 Awaiting for discoveries of unseen dimensions... LHC attracts unprecedented public attention... Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 2 ...in mass media Compact Muon Solenoid as seen by BBC Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 3 ...in mass media Compact Muon Solenoid as seen by BBC Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 3 ...in mass media Compact Muon Solenoid as seen by BBC Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 3 ...in mass media Compact Muon Solenoid as seen by BBC Pavel Nadolsky (SMU) Quarknet workshop August 5, 2009 3 .. -

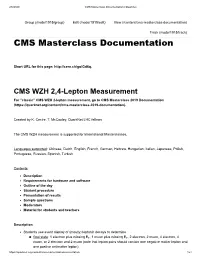

CMS Masterclass Documentation | Quarknet

2/6/2020 CMS Masterclass Documentation | Quarknet Group (/node/1915/group) Edit (/node/1915/edit) View (/content/cms-masterclass-documentation) Track (/node/1915/track) CMS Masterclass Documentation Short URL for this page: http://cern.ch/go/Gd6q. CMS WZH 2,4-Lepton Measurement For "classic" CMS WZH 2-lepton measurement, go to CMS Masterclass 2019 Documentation (https://quarknet.org/content/cms-masterclass-2019-documentation). Created by K. Cecire, T. McCauley, QuarkNet LHC fellows The CMS WZH measurement is supported for International Masterclasses. Languages supported: Chinese, Dutch, English, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Turkish Contents: Description Requirements for hardware and software Outline of the day Student procedure Presentation of results Sample questions Moderators Material for students and teachers Description Students use event display of (mostly) leptonic decays to determine final state: 1 electron plus missing ET, 1 muon plus missing ET, 2 electron, 2 muon, 4 electron, 4 muon, or 2 electron and 2 muon (note that lepton pairs should contain one negative matter lepton and one postive antimatter lepton) https://quarknet.org/content/cms-masterclass-documentation 1/21 2/6/2020 CMS Masterclass Documentation | Quarknet charges of leptons, especially for one lepton plus missing ET primary state: W+, W-, W± (indicating electric charge unknown), neutral particle, zoo charge if W, using curvature of electron or muon tracks, Students use particle counts to find e:µ and W+:W- ratios. Students create mass plots. They find the masses of neutral particle peaks in two mass histograms: 2- lepton and 4-lepton. Histograms are fed automatically upon entry of masses. -

Physics 29000 – Quarknet/Service Learning

Physics 29000 – Quarknet/Service Learning Lecture 1: Introduction Purdue University Department of Physics January 18, 2013 1 What is QuarkNet? http://quarknet.fnal.gov/index.html • Principal Investigators: – Marjorie Bardeen (Fermilab) – Anna Goussiou (Washington) – Dan Karmgard, Mitch Wayne (Notre Dame) • Staff Teachers: – Tom Jordan (Florida) – Ken Cecire (Notre Dame) – Bob Peterson (Fermilab) • And many more… 2 3 What is QuarkNet? • One area of leading edge research into the fundamental laws of nature is Particle Physics… • And in particular, High Energy Physics (HEP) • As researchers, we get to… – Ask big questions like • “What is the origin of mass?” • “Were is all the anti-matter in the universe?” – Develop new technologies for conducting leading edge experiments – Carry out some of the most complex experiments ever constructed – Collaborate with hundreds or thousands of other researchers from around the world • This creates some unique opportunities… 4 What is QuarkNet? • High school outreach: – Valued and supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) – Community benefits from publically funded research – Attract students to pursue careers in science and technology ”QuarkNet: Helping Develop America's Technical Workforce” – Leading edge research is not abstract – it is happening now in your community – Students and teachers can be a part of it! – They are not are not on your own: • 18 HEP experiments • 475 high schools in 24 states • 60 ,000 students per year – Purdue can help get local teachers and students involved. 5 QuarkNet QuarkNet is a national program sponsored by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy , designed to involve high school physics and chemistry teachers in cutting-edge high energy particle physics research.