Midnight Intrusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election Monitor No.49

Euro-Burma Office 10 November 22 November 2010 Election Monitor ELECTION MONITOR NO. 49 DIPLOMATS OF FOREIGN MISSIONS OBSERVE VOTING PROCESS IN VARIOUS STATES AND REGIONS Representatives of foreign embassies and UN agencies based in Myanmar, members of the Myanmar Foreign Correspondents Club and local journalists observed the polling stations and studied the casting of votes at a number of polling stations on the day of the elections. According the state-run media, the diplomats and guests were organized into small groups and conducted to the various regions and states to witness the elections. The following are the number of polling stations and number of eligible voters for the various regions and states:1 1. Kachin State - 866 polling stations for 824,968 eligible voters. 2. Magway Region- 4436 polling stations in 1705 wards and villages with 2,695,546 eligible voters 3. Chin State - 510 polling stations with 66827 eligible voters 4. Sagaing Region - 3,307 polling stations with 3,114,222 eligible voters in 125 constituencies 5. Bago Region - 1251 polling stations and 1057656 voters 6. Shan State (North ) - 1268 polling stations in five districts, 19 townships and 839 wards/ villages and there were 1,060,807 eligible voters. 7. Shan State(East) - 506 polling stations and 331,448 eligible voters 8. Shan State (South)- 908,030 eligible voters cast votes at 975 polling stations 9. Mandalay Region - 653 polling stations where more than 85,500 eligible voters 10. Rakhine State - 2824 polling stations and over 1769000 eligible voters in 17 townships in Rakhine State, 1267 polling stations and over 863000 eligible voters in Sittway District and 139 polling stations and over 146000 eligible voters in Sittway Township. -

ASAA Abstract Booklet

ASAA 2020 Abstract Book 23rd Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) The University of Melbourne Contents Pages ● Address from the Conference Convenor 3 ● 2020 ASAA Organising Committee 4 ● Disciplinary Champions 4-6 ● Conference Organisers 6 ● Conference Sponsors and Supporters 7 ● Conference Program 8-18 ● Sub-Regional Keynote Abstracts 19-21 ● Roundtable Abstracts 22-25 ● Speaker Abstracts ○ Tuesday 7th July ▪ Panel Session 1.1 26-60 ▪ Panel Session 1.2 61-94 ▪ Panel Session 1.3 95-129 ○ Wednesday 8th July ▪ Panel Session 2.1 130-165 ▪ Panel Session 2.2 166-198 ▪ Panel Session 2.3 199-230 ○ Thursday 9th July ▪ Panel Session 3.1 231-264 ▪ Panel Session 3.2 265-296 ▪ Panel Session 3.3 297-322 ● Author Index 323-332 Page 2 23rd Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia Abstract Book Address from the Conference Convenor Dear Colleagues, At the time that we made the necessary decision to cancel the ASAA 2020 conference our digital program was already available online. Following requests from several younger conference participants who were looking forward to presenting at their first international conference and networking with established colleagues in their field, we have prepared this book of abstracts together with the program. We hope that you, our intended ASAA 2020 delegates, will use this document as a way to discover the breadth of research being undertaken and reach out to other scholars. Several of you have kindly recognised how much work went into preparing the program for our 600 participants. We think this is a nice way to at least share the program in an accessible format and to allow you all to see the exciting breadth of research on Asia going on in Australia and in the region. -

Ko Thet Win Aung, Prisoner of Conscience, Dies in Prison

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Public Statement Myanmar: Ko Thet Win Aung, prisoner of conscience, dies in prison Amnesty International is deeply concerned by the death in Mandalay Prison today of student leader and prisoner of conscience Thet Win Aung, aged 34. The organization calls on authorities to initiate a prompt, independent investigation into the causes of Ko Thet Win Aung’s death and to make the findings public. The organization also urges the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) to take urgent steps to protect all prisoners’ health. Ko Thet Win Aung had been imprisoned since 1998 for his part in organizing peaceful small scale student demonstrations which called for improvements to the educational system in Myanmar and for the release of political prisoners. He had been badly tortured during his imprisonment, and had also suffered from a variety of health problems, including malaria. Ko Thet Win Aung had protested the lack of adequate medical treatment and poor diet in prison by going on hunger strike in 2002. By 2005 he was reported to have been unable to walk unassisted. Amnesty International fears for the health of prisoners in Myanmar, and particularly for those debilitated by years’ of imprisonment and ill-treatment, forced to work in poor conditions in labour camps or act as military porters. Prison deaths, including those of political prisoners, are increasing. Poor prison conditions have further deteriorated during 2006. Amnesty International accordingly urges the SPDC to ensure that the authorities take all necessary steps to ensure that the basic rights of prisoners are upheld and their health is not jeopardized further. -

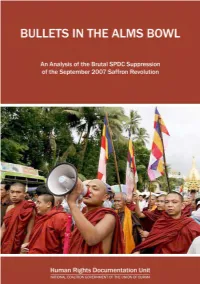

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

The Role of Students in the 8888 Peoples Uprising in Burma

P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand e.mail: [email protected] website: www.aappb.org ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Twenty three years ago today, on 8 August 1988, hundreds of thousands of people flooded the streets of Burma demanding an end to the suffocating military rule which had isolated and bankrupted the country since 1962. Their united cries for a transition to democracy shook the core of the country, bringing Burma to a crippling halt. Hope radiated throughout the country. Teashop owners replaced their store signs with signs of protest, dock workers left behind jobs to join the swelling crowds, and even some soldiers were reported to have been so moved by the demonstrations to lay down their arms and join the protestors. There was so much promise. Background The decision of over hundreds of thousands of Burmese to take to the streets on 8 August 1988 did not happen overnight, but grew out of a growing sense of political discontent and frustration with the regime’s mismanagement of the country’s financial policies that led to deepening poverty. In 1962 General Ne Win, Burma’s ruthless dictator for over twenty years, assumed power through a bloody coup. When students protested, Ne Win responded by abolishing student unions and dynamiting the student union building at Rangoon University, resulting in the death of over 100 university students. All unions were immediately outlawed, heavily restricting the basic civil rights of millions of people. This was the beginning of a consolidation of power by a military regime which would systematically wipe out all opposition groups, starting with student unions, using Ne Win’s spreading network of informers and military intelligence officers. -

11-Monthly Chronology of Burma Political Prisoners for November 2008

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for November 2008 Summary of current situation There are a total of 2164 political prisoners in Burma. These include: CATEGORY NUMBER Monks 220 Members of Parliament 17 Students 271 Women 184 NLD members 472 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and Promoters network 37 Ethnic nationalities 211 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 22 Teachers 25 Media activists 42 Lawyers 13 In poor health 106 Since the protests in August 2007, leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1057 activists have been arrested. Monthly trend analysis In the month of November, at least 215 250 political activists have been sentenced, 200 the majority of whom were arrested in 1 50 Arrested connection with last year’s popular Sentenced uprising in August and September. They 1 00 Released include 33 88 Generation Students Group 50 members, 65 National League for 0 Democracy members and 27 monks. Sep-08 Oct-08 Nov-08 The regime began trials of political prisoners arrested in connection with last year’s Saffron Revolution on 8 October last year. Since then, at least 384 activists have been sentenced, most of them in November this year. This month at least 215 activists were sentenced and 19 were arrested. This follows the monthly trend for October, when there were 45 sentenced and 18 arrested. The statistics confirm reports, which first emerged in October, that the regime has instructed its judiciary to expedite the trials of detained political activists. This month Burma’s flawed justice system has handed out severe sentences to leading political activists. -

June MAY CHRONOLOGY 2020

June MAY CHRONOLOGY 2020 Summary of the Current Kyauk Seik Villagers Tortured by soldiers Situation: 592 individuals are oppressed in Burma due to political activity: 41 political prisoners are serving sentences, 142 are awaiting trial inside Accessed Myanmar Now May prison, 409 are awaiting trial outside prison. WEBSITE | TWITTER | FACEBOOK May 2020 1 ACRONYMS ABFSU All Burma Federation of Student Unions CAT Conservation Alliance Tanawthari CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation EAO Ethnic Armed Organization GEF Global Environment Facility ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross IDP Internally Displaced Person KHRG Karen Human Rights Group KIA Kachin Independence Army KNU Karen National Union MFU Myanmar Farmers’ Union MNHRC Myanmar National Human Rights Commission MOGE Myanmar Oil and Gas Enterprise NLD National League for Democracy NNC Naga National Council PAPPL Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law RCSS Restoration Council of Shan State RCSS/SSA Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army – South SHRF Shan Human Rights Foundation TNLA Ta’ang National Liberation Army YUSU Yangon University Students’ Union May 2020 2 Political Prisoners ARRESTS Ponnagyun woman arrested by military and police Daw Ma Than, a 42-year-old woman from Ponnagyun town, Arakan State was arrested on the morning of May 6. The exact reason for her arrest remains unknown although locals speculated that suspected affiliation with the Arakan Army (AA) was the likely reason. Witnesses reported that the woman was taken by a group of military soldiers, policemen, and a local ward administrator after her home was searched and she was questioned. Locals say that she was taken to Ponnagyun Township police station. -

Pyithu Hluttaw Accepts Motion to Reduce Pro-Democracy Movement Deaths from Non-Infectious Diseases Observed in Yangon

ADAPT TO CHANGE TO BETTER MANAGE EXTREME WEATHER EVENTS PAGE-8 (OPINION) PARLIAMENT NATIONAL Amyotha Hluttaw convenes ninth-day State Counsellor sends condolences on meeting of 13th regular session demise of Sushma Swaraj PAGE-2 PAGE-3 Vol. VI, No. 114, 9th Waxing of Wagaung 1381 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Friday, 9 August 2019 President U Win Myint sends Message of State Counsellor sends Message of Felicitations on Singapore National Day Felicitations on Singapore National Day U WIN MYINT, President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, has sent a DAW AUNG SAN SUU KYI, State Counsellor of the Republic of the Union of message of felicitations to Madam Halimah Yacob, President of the Republic Myanmar, has sent a message of felicitations to Mr Lee Hsien Loong, Prime of Singapore, on the occasion of the 54th Anniversary of the National Day of the Minister of the Republic of Singapore, on the occasion of the 54th Anniversary of Republic of Singapore, which falls on 9 August 2019.—MNA the National Day of the Republic of Singapore, which falls on 9 August 2019.—MNA 31st anniversary Pyithu Hluttaw accepts motion to reduce pro-democracy movement deaths from non-infectious diseases observed in Yangon A ceremony to mark the 31st anniversary of the 1988 pro-democracy move- ment was held yesterday in Yangon. The ceremony was attended by Yangon Re- gion Chief Minister U Phyo Min Thein, Yangon Mayor U Maung Maung Soe, Deputy Mayor U Soe Lwin the Deputy Speaker of the Yangon Re- gion Hluttaw, member of the Yangon Region cabinet, stu- dents who participated in the movement, and the people. -

Free All Political Prisoners, Free Aung San Suu Kyi, Free Burma

BURMA REPORT August 2007 jrefrmh = rwS wf r;f Issue N° 50 August 24, 2007 - Associated Press Arrests thwart new Myanmar protest THE BURMANET NEWS - August 24, 2007 Issue # 3274 - "Editor" <[email protected]> - www.burmanet.org Myanmar's military junta moved swiftly Friday to crush the latest in a series of protests against fuel price hikes, arresting more than 10 activists in front of Yangon City Hall before they could launch any action, witnesses said. The arrests came after protests spread beyond the main city of Yangon, and amid mounting international condemnation of the government's suppressionm of the peaceful, but rare, displays of opposition in the tightly controlled country. Demonstrators on Thursday had marched through the oil-producing town of Yaynang Chaung to protest the fuel price hikes. The protest , the first known of outside Yangon , ended peacefully, said residents who requested anonymity for fear of government reprisals. Another protest planned there for Friday was canceled after authorities agreed to reduce bus fares, which had been raised as a result of the fuel price increases. Nevertheless, in Yangon, rumors swirled Friday of more upcoming demonstrations. Myanmar's ruling junta has been widely criticized for human rights violations, including the 11-year house arrest of opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. The junta tolerates little public dissent, sometimes sentencing activists to long jail terms for violating broadly defined security laws. The activists arrested Friday mostly belonged to a recently formed groupm, called the "Myanmar Development Committee," which in February staged its first protest in busy downtown Yangon holding placards calling for better health and social conditions and complaining of economic hardship. -

The Death of Democracy Activists Behind Bars

Eight Seconds of Silence: The Death of Democracy Activists Behind Bars 1 Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) 2 Eight Seconds of Silence: The Death of Democracy Activists Behind Bars 3 Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) Publishing and Distribution Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma) May 2006 Copy 1500 Address AAPP P.O Box 93 Mae Sot Tak Province 63110 THAILAND Email [email protected] Website www.aappb.org 4 Eight Seconds of Silence: The Death of Democracy Activists Behind Bars Acknowledgements In writing this report, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) seeks to honor the democracy activists who died while behind bars. They are modern day martyrs in the struggle to free Burma. We also commend the bravery of the families of deceased democracy activists for their willingness to share information regarding their loved ones, and for their courage in calling on the authorities to reveal the true circumstances surrounding their loved one’s death. We would like to thank all the former political prisoners, democracy and human rights activists who provided information to us. We likewise appreciate the efforts of the staff and members of the AAPP to compile information, provide translations, write the report and assist with editing. We further thank the staff and members of Burma Action Ireland and the US Campaign for Burma for their editorial comments which helped us to improve on the content of the report. We also wish to thank them, and Burma Campaign UK, for helping our report reach the international community. We appreciate the time taken by Ye Tun Oo to complete the layout of the report. -

Neither Saffron Nor Revolution

Institut für Asien- und Afrikawissenschaften Philosophische Fakultät III der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin NEITHER SAFFRON NOR REVOLUTION A Commentated and Documented Chronology of the Monks’ Demonstrations in Myanmar in 2007 and their Background PART I Hans-Bernd Zöllner Südostasien Working Papers No. 36 Berlin 2009 Hans-Bernd Zöllner NEITHER SAFFRON NOR REVOLUTION A Commentated and Documented Chronology of the Monks’ Demonstrations in Myanmar in 2007 and their Background PART I Südostasien Working Papers No. 36 Berlin 2009 SÜDOSTASIEN Working Papers ISSN: 1432-2811 published by the Department of Southeast Asian Studies Humboldt-University Unter den Linden 6 10999 Berlin, Germany Tel. +49-30-2093 6620 Fax +49-30-2093 6649 Email: [email protected] Cover photograph: Ho. (Picture Alliance / Picture Press) Layout: Eva Streifeneder The Working Papers do not necessarily express the views of the editors or the Institute of Asian and African Studies. Alt- hough the editors are responsible for their selection, responsibility for the opinions expressed in the Papers rests with the aut- hors. Any kind of reproduction without permission is prohibited. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 FOREWORD 7 1 INTRODUCTION 9 2 GLIMPSES INTO HISTORY: ECONOMICS, PROTESTS AND STUDENTS 12 2.0 From 1824 to 1988 – In Fast Motion 12 2.1 From 1988 to 2007 16 3 FROM AUGUST 15 TO SEPTEMBER 5 25 3.0 Narration of Events 25 3.1 The Media 28 3.2 Summary and Open Questions 29 4 PAKOKKU 35 4.0 Preliminary Remarks 35 4.1 Undisputed facts 35 4.2 On the Coverage of the Events -

LAST MONTH in BURMA NOVEMBER News from and About Burma 2008

LAST MONTH IN BURMA NOVEMBER News from and about Burma 2008 215 political activists sentenced in November The military junta sentenced at least 215 political activists and monks during November, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP). The first trial of activists arrested in connection with last year’s uprising in August and September began on 8 October 2007. Since then at least 384 activists have been sentenced. The sentences recently handed down range from 4 months on charges of ‘contempt of court’ for National League for Democracy (NLD) lawyers U Khin Maung Shein and U Aung Thein, to life imprisonment plus 8 years for Human Rights Defenders and Promoters network founding member U Myint Aye on explosives charges. Zarganar, Burma’s most famous comedian and who was arrested in Zarganar connection with his efforts to co-ordinate voluntary relief efforts after May’s Cyclone Nargis, received sentences totaling 59 years. Two other cyclone aid volunteers were also sentenced at the same trial - journalist, social worker and former political prisoner Zaw Thet Htwe was sentenced to a total of 19 years and Thant Zin Aung was sentenced to a total of 18 years. All Burma Monks’ Alliance leader U Gambira, who played a leading role in last year’s Saffron Revolution, was given sentences totaling 68 years. Twenty-three members of the 88 Generation Students Group, who led the Pyone Cho, Ko Ko Gyi, Min Ko protests against fuel price hikes in August last year, were given sentences Naing and Htay Kywe of at least 65 years each.