Peasants Into Syrians KEVIN W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Southern Accent July 1953 - September 1954

Southern Adventist University KnowledgeExchange@Southern Southern Accent - Student Newspaper University Archives & Publications 1953 Southern Accent July 1953 - September 1954 Southern Missionary College Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/southern_accent Recommended Citation Southern Missionary College, "Southern Accent July 1953 - September 1954" (1953). Southern Accent - Student Newspaper. 33. https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/southern_accent/33 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Publications at KnowledgeExchange@Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Southern Accent - Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of KnowledgeExchange@Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOUTHERN msmm college UBRMV THE OUTH^^ ACCENT Souchern Missionary^ollege, Collegedale, Tennessee, July 3. 1953 o lleven SMC Graduates Ordained Young Men Ordained to M^ Kennedy Supervises Varied Gospel Ministry f. at Five Iprog am of Summer Activities Southern Union Camp Meetings fcht chapel scat Wednesday e c n ng br ngs these comn ents for once tadi week we ha\e chapel Many % r cd ch-ipel progran s ha e been '> p anned bj Dr R chard Hammill of the college rfOMffliililiins ! Thursday udenb and it d(-r e\en ng at the ball field br ngs torth to bu Id up cred cheers as a runner si des the hon e or as the umpire calls 6tr kc Three Student o^ram Comm ... and h ult) al ke mansh p of Profc share the thr II of a hon e run V d) hi\e out! ned Come th me -

Employers, Workers, and Wages Under OASI, April–September 1954

each age under 20, was the largest for (1 percentage point) during the year were 23 percent fewer than in 1953; this age group in any January-June to 65 percent (table 5). they were less than the number in period since 1946, when-with the There is a downward trend in the 1950 for the Arst time since coverage entry or reentry of demobilized mili- number of persons aged 20 and over extension under the 1950 amend- tary personnel into the labor market who do not have account numbers. ments first became effective. -there was a sharp reduction in the Mainly as a result of this trend, the A decrease from the number is- number of youths getting jobs. Al- number of accounts established for sued in 1953 was registered at each though there was a decrease in the members of this age group decreased age over 20. but the decline for per- absolute number of these younger for, the third consecutive year. The sons aged 60 and over was consider- applicants in 1954, the proportion 956,000 account numbers issued to ably smaller than for the entire they formed of the total rose slightly persons aged 20 and over in 1954 group aged 20 and over. The rela- tively small decrease (13 percent) Table 3.-Applicants for account numbers, by sex, race, and age group, 1954 shown for this older age group is attributable to an increase in the fourth quarter in the number of these elderly applicants-many of White 1 Negro Total White 1 Negro Total White 1 Negro them farm operators and professional self-employed persons to whom cov- TotaL-. -

Judgement No. 58

306 United Nations Administrative Tribunal Nations Staff Regulations and Rules concerning the right of appeal to the Tribunal were available to the Applicant. 8. In view of the foregoing, the Tribunal, without making any findings on other issues, decides that it has jurisdiction to consider the merits of this case. (Signatures) Suzanne BASTID CROOK Sture PET&N President Vice-President Vice-Presiednt Jacob M. LASHLY Mani SANASEN Alternate Executive Secretary Geneva, 9 September 1955 Judgement No. 58 Case No. 61: Against: The Secretary-General Kamal Kumar Chattopadhyay of the United Nations THE ADMINISTRATIVE TRIBUNAL OF THE UNITED NATIONS, Composed of Madame Paul Bastid, President ; the Lord Crook, Vice-President; Mr. Sture Pet&, Vice-President ; Mr. Jacob Mark Lashly, alternate ; Whereas Kamal Kumar Chattopadhyay, former Deputy Director of the Information Centre of the United Nations at New Delhi, filed an application to the Tribunal on 26 February 1955 requesting : (a) The rescission of the Secretary-General’s decision of 25 July 195 3 to terminate his temporary-indefinite appointment ; (b) The award of $28,380 as minimum compensation for wrongful dismissal ; (c) Alternatively, in the event that the Secretary-General avails himself of the option given to him under article 9 of the Statute of the Tribunal, the award of $28,900 as compensation for the injury sustained ; Whereas the Respondent filed his answer to the application on 16 May 1955; Whereas the Tribunal heard the parties in public session on 31 August 1955 ; Whereas the facts as to the Applicant are as follows : Judgement No. 58 307 ~- The Applicant entered the service of the United Nations on 1 January 1947 under a temporary-indefinite appointment, as Acting Chief of the New Delhi Information Centre. -

AERIAL INCIDENT of 4 SEPTEMBER 1954 (UNITED STATES of Ablerica V

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE PLEADINGS, ORAL ARGUMENTS, DOCUMENTS AERIAL INCIDENT OF 4 SEPTEMBER 1954 (UNITED STATES OF AblERICA v. UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALLST REPUBLICS) COUR INTERNATIONALE DE JUSTICE MÉMOIRES, PLAIDOIRIES ET DOCUMENTS INCIDENT AÉRIEN DU 4 SEPTEMBRE 1954 (ÉTATS-UNIS D'AMÉRIQUE c. UNION DES RÉPUBLIQUES SOCIALISTES SOVIÉTIQUES) APPLICATION INSTITUTING PROCEEDINGS AND PLEADINGS SECTION A.-APPLICATION INSTITGTING PROCEEDINGS PREMIÈRE PARTIE REQUÊTE INTRODUCTIVE D'INSTANCE ET MÉMOIRES SECTION A. - REQUETE INTRODUCTIVE D'INSTANCE APPLICATION INSTITUTING PROCEEDINGS ' THEAGENTOFTHEGOVERNMENTOFTHEUNITED STATES OF AMERICA TO THE REGISTRAR OF THE INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE DEPARTMENTOF STATE, \YASHINGTON. JU~Y25, 1958. Sir: I. This is a written application, in accordance with the Statute and Rules of the Court, suhmitted hy the Government of the United States of America instituting proceedings against the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on account of certain willful acts committed by military aircraft of the Soviet Government on September 4, 1954, in the international air space over the Sea of Japan against a United States Navy Pz-V-type aircraft, commonly known as a Neptune type, and against its crew: The subject of the dispute and a succint statement of the facts and the grounds upon which the claim of the Government of the United States of America is based are adequately set forth in a note delivered to the Soviet Government on Octoher 12, 1956. A copy of the note is attached to this application as an annex. The Soviet Government has asserted its contentions of fact and of law with reference to the United States Government's claim in other diplo- matic correspondence on this subject, most recently in a note of January ~1,1957,a copy of which is also attached to this application as an annex. -

Effect of Increased OASI Benefits on Public Assistance, September

Table L-Old-age assistance and aid to dependent children: Aged per- Notes and Brzef Reports sons and families with children re- ceiving both assistance payments Effect of Increased OASI To help State agenciesin adjusting and OASI benefits, by State, Sep- Benefits on Public the amount of the assistance pay- tember 1954 1 ments made to persons who were re- Assistance, September- OAA recip- ADC fami- ceiving old-age and survivors insur- ients receiv- lies receiv- December 1954 * ance benefits before the amendments, in$,X&I 1 ing OASI a set, of conversion tables was pre- benefits The 1954 amendments to the Social IL--- Security Act that became effective pared by the Bureau of Old-Age and in September included provisions in- Survivors Insurance in cooperation state creasing benefit payments for all cur- with the Bureau of Public Assistance. rent beneficiaries of old-age and sur- These tables, which showed the bene- vivors insurance and permitting im- fit paid for August and the amount mediate entitlement to benefits of a of the increase for September, were group of persons who had heretofore used for all single beneficiaries and __]-I__ - been excluded. This new group con- for all family groups consisting of Total, 53 States :.mm.-4 L69.0351 18.2 26,325~ 4.5 two beneficiaries except families con- ---- sists of surviving parents, widows, Alabama-. _.______..___. 1.92& 644 3.9 and children of individuals who died sisting of two children only. All Alaska...---.-- _____ ---. 4041 2::: 5i 5.3 Arizona- _____ ________ 2,638 20.3 207 4.8 after 1939 and before September 1, other beneficiary cases, estimated to Arkansas.~ ..___ _...__. -

Washington, Wednesday, September 14, 1955 TITLE 6

wanted Washington, Wednesday, September 14, 1955 TITLE 6— AGRICULTURAL CREDIT Farms in the Domestic Beet Sugar Area, CONTENTS 1955 Crop (19 F. R. 7260), as amended, Chapter 111—Farmers Home Adminis (20 F. R. 1635), the Agricultural Stabili Agricultural Marketing Service Pa§® tration, Department of Agriculture zation and Conservation Oregon State Proposed rule making: Committee has issued the bases and pro Milk in Central Arizona_______ 6751 Subchapter E—-Account Servicing cedures for dividing the State into pro Rules and regulations: [Administration Letter 318 (450) ] portionate share areas and establishing ' Dates, domestic, produced or individual farm proportionate shares P art 361—R o u t in e packed in Los Angeles and from the allocation of 17,685 acres estab Riverside Counties, Calif.; RETURN OP NOTES AFTER SATISFACTION OF lished for Oregon by the determination. budget of expenses and rate of JUDGEMENTS Copies of these bases and procedures are assessment for 1955-56 crop available for public inspection at the Section 361.7 of Title 6, Code of Fed year________ _________ _____ 6730 office of such committee at the Ross Potatoes, Irish, grown in idaho r eral Regulations (19 F. R . 2762), is hereby Building, 4th Floor, 209 S. W. 5th Avenue, amended by the addition of a new para and Oregon; limitation of Portland, Oregon, and at the offices of the shipments____________ _____ 6729 graph (f) as follows: Agricultural Stabilization and Conserva § 361.7 Miscellaneous servicing on tion Committees in the sugar beet pro Agriculture Department operating loan accounts. * * * ducing counties of Oregon. These bases See Agricultural Marketing Serv (f) Return of notes after satisfactionand procedures incorporate the follow ice ; Farmers Home Administra of judgments. -

September 1955) Guy Mccoy

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 9-1955 Volume 73, Number 09 (September 1955) Guy McCoy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation McCoy, Guy. "Volume 73, Number 09 (September 1955)." , (1955). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. etude 90 cents S ZVLS September 1999 / THE A MUSIC OF AMERICA! popular songs... S the hits of today and the endutlng standards of tomorrow. production numbers... hit tunes from the most successful Broadway shows, past and present, and notable Hollywood musical films rhythm and blues... new Latin tempos, favorite blues, syncopation c and |an— all unmistakably American. folk songs... work songs, play songs, regional songs, mirroring the history of the American people. sacred music... liturgical music, songs of faith, gospel hymns expressing the religious beliefs of Americans, symphonic and A concert works... great classics, daring innovators as well as creators In traditional patterns More than 3,900 writers and publishers are constantly adding new works P to the extensive ASCAP repertory, American Society of Composers, Authors If you are interested in seeing and hearing Ibis lovely The instrument, write for the name of your nearest dealer. -

Chapter VII PRACTICES RELATIVE to RECOMMENDATIONS to the GENERAL ASSEMBLY REGARDING the ADMISSION of NEW MEMBERS

Chapter VII PRACTICES RELATIVE TO RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY REGARDING THE ADMISSION OF NEW MEMBERS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTORY NOTE . 85 PART I. TABLEOFAPPLICATIONS, 1952-1955, ASD OFACTIONSTAKESTHEREONBYTHESECURITY COUNCIL Note 85 A. Applications recommended by the Security Council ............................... 85 B. Applications which failed to obtain a recommendation ............................ 85 C. Discussion of the question in the Council from 1952-1955 ........................... 86 D. Applications pending on 1 January 1952 ......................................... 86 E. Applications submitted betweca 1 January 1952 and 31 December 1955 .............. 87 F. Votes in the Security Council (1952-1955) on draft resolutions and amendments concern- ing applications for admission tc membership in the United Nations ................. 87 **PART II. CONSIDERATION OF THE AD.-- :IOS OF AMENDMENT OF RULES 58,59 AND 60 OF THE PROVISIONAL RULES OF PROCEDURE PART III. PRESENTATION OF APPLICATIONS .- Note . ..-.......................................................-............. -,9l -- k PART IV. REFERENCE OFAPPLICATIONSTOTHECO~~ITTEEONTHEADMISSIONOFNEWMEMBERS Note 91 A. Before a recommendation has been forwarded or a report submitted to the General Assembly . 92 l *1. Applications referred to the Committee by the President . 92 l *2. Applications referred to the Committee by decision of the Security Council . 92 3. Applications considered by the Security Council without reference to the Com- mittee . 92 “4. Applications reconsidered by the Security Council after reference to the Com- mittee . 95 B. AFTER AN APPLICATION HAS BEEN SENT BACK BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY TO THE SECURITY COUNCIL FOR RECONSIDERATION l *1. Applications referred to the Committee by the President . 95 2. Applications reconsidered by the Security Council without reference to the Com- mittee . 95 Note . 95 PART V. PROCEDURES IN THE CONSIDERATION OF APPLICATIONS WITHIN THE SECURITY COUNCIL Note 95 *+A. -

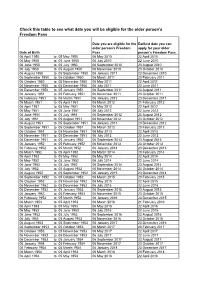

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Taylor University Bulletin Annual Report 1954-1955 (September 1955)

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Taylor University Bulletin Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections 9-1-1955 Taylor University Bulletin Annual Report 1954-1955 (September 1955) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu-bulletin Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor University Bulletin Annual Report 1954-1955 (September 1955)" (1955). Taylor University Bulletin. 70. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu-bulletin/70 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Taylor University Bulletin by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAYLOR UNIVERSITY BULLETIN Upland, Indiana ANNUAL REPORT 1954-55 Foreword The greatest challenge of higher education that has ever before con fronted this country is now before us. We are already aware of the growth that has come to college population this past year, it being the college year of the beginning of "The Impending Tidal Wave of Students." By 1970, or before, no doubt the colleges of the country will have double the present number of students seeking enrollment. The challenge, I believe, will be greater in our Christian colleges. This will be true, particularly if it is correct that there is at least a mild revival of interest in the church—and especially that branch of the church that we call evangelical. We cannot afford simply to sit idly back and let come what may. If evangelical Christianity is to march forward under the banner of Christ it will take much hard-headed planning and consecration. -

September 22, 1955 Letter, I. Vinogradov and M. Yakovlev to the CPSU Central Committee

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 22, 1955 Letter, I. Vinogradov and M. Yakovlev to the CPSU Central Committee Citation: “Letter, I. Vinogradov and M. Yakovlev to the CPSU Central Committee,” September 22, 1955, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, RGANI, f. 5, op. 28, d. 347. Department for Relations with Foreign Communist Parties (International Department of the Central Committee), 1953-1957, microfilm, reel 83. Contributed by Roham Alvandi and translated by Gary Goldberg. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/119702 Summary: This letter describes the Bulgarian government's request that Nyuzkhet Hijeran Nihat be sent to lecture in Turkish language and literature for one year at Sofia University. However, the CPSU CC cannot recommend him because of his previous unsatisfactory work while in Moscow. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document [CPSU CC stamp: 35402 22 September 1955 Subject to return to the CPSU CC General Department] TO THE CPSU CENTRAL COMMITTEE The Bulgarian government has addressed a request to send Nyuzkhet Hijeran Nihat to lecture for one year in Sofia University in Turkish language and literature. Nihat is a Soviet citizen and a CPSU member. He worked in Leningrad State University as a Turkish language instructor and scholar. According to a report of LGU Prorector Cde. Ivanov-Omsky, Nihat has insufficient training to teach language and scholarly work, has not coped with the work, and treats it without proper diligence. Then Nihat was sent to Moscow, seconded to the USSR Academy of Sciences' Institute of Oriental Studies to take a graduate course and prepare a dissertation.