Print/Download This Article (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sacramento Ragtime Society Newsletter

SACRAMENTO RAGTIME SOCIETY NEWSLETTER by Chris Bradshaw by Keith Taylor, other festival performers o diamond in the rough, this pol- Andrew Barrett, John Remmers, the Brad- Nished gem of a festival, held August shaws, and Stevens Price joined him for a 14-16, 2009 in Sutter Creek, glimmered festival teaser. Good food, a great piano and glittered from beginning to end. An and a warm and encouraging audience unique celebration of vintage American made for a wonderful evening. Music encompassing ragtime, stride, boo- As is tradition, Friday’s festival opened gie and blues, the 11th annual Sutter in the Ice Cream Emporium amidst the rev- Creek Ragtime Festival sparkled with tal- erie of an excited, ice cream spooning, ent, enthusiastic listeners and the special soda slurping audience with Keith Taylor, chemistry that just happens when you dishing up a tasty original take on Original bring together professional performers Rags (1899) by Scott Joplin. Another with die-hard ragtime fans. The outcome-a standout performance during the festival melange of theater concerts, youth perform- from Keith’s eclectic repertoire was his ances, silent movies, instrumental en- own Ghosts of Sutter Creek (2007), one of sembles, the Town Square Harmonizers barbershop quartet, two great festival See continued on page 4 shows and plenty of fine solo sets all joy- ously celebrating the In This Issue best of the ragtime era--was a series of ma- gical moments strung together as gleaming pearls, from the first note to the last. Setting the tone was the pre-festival event held Thursday evening at the Green- horn Creek Resort in Angels Camp. -

The Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove Wishes to Thank All the Supporters and Volunteers for Their Generous Help with the Annual Good Old Days Pancake Breakfast

The Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove wishes to thank all the supporters and volunteers for their generous help with the annual Good Old Days Pancake Breakfast. The Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove is a private, charitable international organization, dedicated to improving the lives of children and their community. The Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove sponsors the Scout Troops, Cub Scout Packs, Pony League Baseball Teams, Lacrosse teams, athletic programs at Pacific Grove schools, science camps at elementary schools and organizes the Santa Project to help needy children. The Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove also supports the Meals on Wheels program, the Gateway Center, the maintenance of the building and Gazebo at Jewel Park, Salvation Army bell ringers, installing smoke detectors in every home in Pacific Grove and many more community service programs. Go to http://kiwanispg.org to find out more about Kiwanis International and the Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove and how you can join in supporting your community. The Pacific Grove Kiwanis Club meetings are every other Thursday, at 7:30 am, at First Awakenings Restaurant 125 Oceanview Blvd. near the Aquarium. Contact Mike Niccum 647-5604 or Sherry Sands 372-4421 for more information about the Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove. The Kiwanis Club of Pacific Grove Pancake Breakfast Celebrates Good Old Days with RAGTIME The Piano Music of the Good Old Days Ragtime was the popular American music of the good old days. Each "rag" selected was published on the same year of a notable historical moment in Pacific Grove's "Good Old Days". Please enjoy your Kiwanis pancake breakfast and go back in time, to the good old days, with the ragtime piano time machine. -

Piano Works by African American Composers

Piano Works by African American Composers Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins - Thomas Bethune (1849-1908) A blind, slave pianist, autistic savant, musical prodigy from Georgia • The Battle of Manassas (1866) • The Oliver Gallop (1860) • Water in the Moonlight (1892) • Sewing Song (1889) • Rain Storm (1865) • March Timpani (1880) • Reve Charmant (1881) • Wellenklange: Voices of the Waves (1882) Scott Joplin (1867-1917) The “King of Ragtime”, an African American composer and pianist, achieved fame for his ragtime compositions • Great Crush Collision • Something Doing (1903) • Heliotrope Bouquet (1907) March (1896) • Weeping Willow (1903) • Fig Leaf Rag 1908) • Combination March (1896) • Palm Leaf Rag (1903) • Sugar Cane (1908) • Harmony Club Waltz • The Sycamore (1904) • Sensation (1908) (1896) • The Favorite (1904) • Pine Apple Rag (1908) • Original Rags (1899) • The Cascades (1904) • Pleasant Moments 1909) • Maple Leaf Rag (1899) • The Chrysanthemum • Wall Street Rag (1909) • Swipesy Cakewalk (1900) (1904) • Solace (1909) • Peacherine Rag (1901) • Bethena (1905) • Country Club (1909) • Sunflower Slow Drag • Blinks’ Waltz (1905) • Euphonic Sounds (1909) (1901) • The Rosebud March • Paragon Rag (1909) • Augustan Club Waltz (1905) • Stoptime Rag (1910) (1901) • Leola (1905) • Felicity Rag (1911) • The Easy Winners (1901) • Eugenia (1906) • Scott Joplin’s New Rag • Cleopha (1902) • The Ragtime Dance 1906) (1912) • A Breeze from Alabama • Antoinette (1906) • Kismet Rag (1913) (1902) • The Nonpareil (1907) • Silver Swan Rag (1914) • Elite Syncopations -

Piano Roll Summary

This roll was originally recorded for the Connorized McTammany, John Music Company and was acquired by QRS in the 1920s 1915 The Technical History of the Player. New York: (QRS 1987:16). Comparison of the roll to Joplin's 1899 Musical Courier. published score (Lawrence 1971), reveals no added Montgomery, Michael, Trebor Jay Tichenor and John octaves or other standard types of embellishment and Edward Hasse none of the arpeggiation which Connorized was famous 1985 Ragtime on Piano Rolls. 111: John Edward Hasse for. Aside from being suspiciously precise in meter (and (ed.). Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Joplin was known for his precision) the roll reveals little Music. New York: Schirmer. that suggests editing. Although an extended discussion of my analysis of the Maple Leaf roll is not appropriate for Ord-Hume, Arthur J. W. G. this article, suffice to say that the roll provides a precise 1973 Clockwork Music. New York: Crown Publishers. graphic representation of rhythmic techniques which have been described by other researchers metaphorically (see: QRS Incorporated Schafer 1977:56). 1981 Player Roll Catalog. Buffalo, N. Y.: QRS Inc. Perhaps more important to musicologists than the value 1987 Player Piano Owner's Guide. Buffalo N. Y.: QRS of piano rolls in formal analysis is the recognition of Inc. player piano music as a creative genre in its own right. Roehl, Harvey N. The artistry of piano roll arrangers is an important part of 1976 Player Piano Treasury. Vestal N. Y.: The Vestal the history of early twentieth century popular music. Press. While many of these "behind the scenes" artists were lost to historical oblivion, a few have received recognition for Schafer, William John and Johannes Reidel their work. -

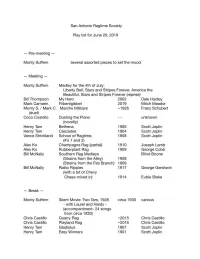

Monty Suffern Several Assorted Pieces to Set the Mood

San Antonio Ragtime Society Play list for June 29, 2019 - Pre-meeting - Monty Suffern several assorted pieces to set the mood -Meeting - Monty Suffern Medley for the 4th of July: Liberty Bell, Stars and Stripes Forever, America the Beautiful, Stars and Stripes Forever (reprise) Bill Thompson My Hero 2002 Dale Hadley Mark Camann Flibertigibbet 2019 Mitch Meador Monty S. I Mark C. Marche Militaire -1826 Franz Schubert (duet) Coco Costello Dusting the Piano unknown (novelty) Henry Tam Beth en a 1905 Scott Joplin Henry Tam Cascades 1904 Scott Joplin Vance Strickland School of Ragtime, 1908 Scott Joplin (#'s 1 and 2) Alex Ko Champagne Rag (partial) 1910 Joseph Lamb Alex Ko Rubberplant Rag 1909 George Cobb Bill McNally Southern Rag Medleys Blind Boone (Strains from the Alley) 1908 (Strains from the Flat Branch) 1909 Bill McNally Rialto Ripples 1917 George Gershwin (with a bit of Chevy Chase mixed in) 191 4 Eubie Blake -Break- Monty Suffern Silent Movie: Two Tars, 1928 circa 1930 various - with Laurel and Hardy - (accompaniment- 24 songs from circa 1930) Chris Castillo Quarry Rag -2015 Chri s Castillo Chris Castillo Playland Rag -2016 Chris Castillo Henry Tam Gladiolus 1907 Scott Joplin Henry Tam Easy Winners 1901 Scott Joplin San Antonio Ragtime Society Meeting: April 27, 2019 List of performers and music played Performer Title Composer Year The Entertainer Weeping Willow The Ragtime Dance Jimmy Drury Scott Joplin The Easy Winners Leola Elite Syncopations Vicki McRae Red Rose Rag Percy Wenrich 1911 Bill Thompson Race Horse Rag Mike Bernard 1911 Vicki McRae & Cleopha - March & Two Step Scott Joplin 1902 Bill Thompson (duet - arr. -

James Scott Pianist, Composer, and Teacher 1885-1938

Missouri Valley Special Collections: Biography James Scott Pianist, Composer, and Teacher 1885-1938 by David Conrads Ragtime is a uniquely American musical form and a precursor of jazz. It flourished around the turn of the century, and many of its leading practitioners had connections to Missouri. James Scott, who was born in Neosho and died in Kansas City, Kansas, was one of the biggest names in ragtime, second only to the great pianist and composer Scott Joplin. James Scott, known as the “Little Professor,” was a piano prodigy, blessed with perfect pitch. As a boy, he took piano lessons from a local teacher in Neosho and was an accomplished pianist by the time his family moved to Ottawa, Kansas, around 1899. The family moved to Carthage, Missouri, in 1901, where James got a job at the Dumars Music Company. Dumars published Scott’s first rag, “A Summer Breeze--March and Two-Step,” in 1903 when he was 17 years old. In 1906, he traveled to St. Louis where he studied with Scott Joplin. Joplin’s publisher, the Stark Music Company, took on James Scott and published “Frog Legs” in 1906, one of his best- known compositions. In 1914, Scott moved to Kansas City, where he taught piano and continued to write music. He was also appointed music director of a theater chain that operated the Lincoln, Eblon, and Panama theaters, all located in the thriving 18th & Vine area. He worked as a pianist, organist, arranger, and bandleader until around 1930, when silent movies were replaced by sound. As the popularity of jazz increased through the 1920s, ragtime began to die out. -

RLP JAZZ ARCHIVES 12-126 RAGTIME Piano Roll Classics SCOTT JOPLIN, JAMES SCOTT

RIVERSIDE RLP JAZZ ARCHIVES 12-126 RAGTIME Piano Roll Classics SCOTT JOPLIN, JAMES SCOTT. TOM TURPIN, others All selections on Side 1, and # l and 2 on Side 2, probably played by their composers; other four selections by unknown pianists. The recordirws that make up this LP comprise a unique lo put across this remarkable music to all of America. and important ;egment of the history of An:erican 1.nusic. SIDE 1 If Sedalia was the birthplace of ragtime, St. Louis antique~: became its capital. There the big man tin more ways But they are most ce!·tainly not mere musical (James Scott) they are exciting ragtime performances that are every bil l. Grace and Beauty than one) was Thomas Million Turpin (1873-1922), a six-foot, 300-pound saloonkeeper of legendary good as alive and compelling today as when they were first 2. Ragtime Oriole (James Scott) l'layed-which was in some instances more than half a humor, who wrote few rags but played many, and who (Tom Turpi11) fathered the more brilliant, swift and showy "St. Louis century ago. 3. St. Louis Rag school" of ragtime. His rhythmic St. Louis Rag was ( .: oseph f,amb) To begin with, these were not recordings al all- they 4. American Beauty Hag written in 1903. antedate all but the very earliest of records. They were 5. Scott Joplin's New Hag (Scott Joplin) oricrinally a series of oblong holes c;.it on long sheets of James Scott ( 1886-19381 ranks with Joplin and Turpin pa1~er, rolled into cylinders and played in both home~ 6. -

Ragtime Ragtime Preceded Jazz and Was a Popular Style of American Music from About 1895 to 1917

Ragtime Ragtime preceded jazz and was a popular style of American music from about 1895 to 1917. Ragtime was created by honky-tonk pianists, borrowing from syncopated music played by uneducated musicians from the south who were playing banjo, guitar, mandolin and fiddle, and is known for its steady rhythm in the bass and a syncopated melody, usually in two-four time. Ragtime compositions by Scott Joplin and many other ragtime composer/pianists became a fad and the published sheet music was widely sold throughout the country and also spread to Europe. Scott Joplin, known as the “King of Ragtime,” was the best known ragtime composer and his composition “The Entertainer” caused a revival of ragtime in 1974 when it was used in the popular motion picture “The Sting.” Ragtime in Missouri In describing the history of ragtime, the Library of Congress has said: “Ragtime seemed to emanate primarily from the southern and midwestern states with the majority of activity occurring in Missouri.” Scott Joplin grew up in Texarkana, Texas, traveled around the south as a musician, and came to Sedalia, Missouri in 1894, making his living teaching piano. His publication of “Maple Leaf Rag,” named for a club in Sedalia, became a huge hit around the country. John Stark was a beginning music publisher in Sedalia who heard Joplin play “Maple Leaf Rag,” published it and sold over a million copies, permitting Stark to open an office in St. Louis. Joplin moved to St. Louis in 1901, staying there until 1907 when he moved to New York. Other top St.