Case Studies Into the Invisible Presence of Aboriginal People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Cultures 11/11

.. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board, Australia Council PO Box 788 Strawberry Hills NSW 2012 Tel: (02) 9215 9065 Toll Free: 1800 226 912 Fax: (02) 9215 9061 Email: [email protected] www.ozco.gov.au cultures . WRITING ..... Protocols for Producing Indigenous Australian Literature An initiative of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait ISBN: 0 642 47240 8 Islander Arts Board of the Australia Council Writing Cultures: Protocols for Producing Indigenous Australian Literature Recognition and protection 18 contents Resources 18 Introduction 1 Copyright 20 Using the Writing Cultures guide 2 What is copyright? 20 What are protocols? 3 How does copyright protect literature? 20 What is Indigenous literature? 3 Who owns copyright? 20 Special nature of Indigenous literature 4 What rights do copyright owners have? 21 Collaborative works 21 Indigenous heritage 5 Communal ownership vs. joint ownership 21 Current protection of heritage 6 How long does copyright last? 22 Principles and protocols 8 What is the public domain? 22 Respect 8 What are moral rights? 22 Acknowledgement of country 8 Licensing for publication 22 Representation 8 Assigning copyright 23 Accepting diversity 8 Publishing contracts 23 Living cultures 9 Managing copyright to protect your interests 23 Indigenous control 9 Copyright notice 23 Commissioning Indigenous writers 9 Moral rights notice 24 Communication, consultation and consent 10 When is copyright infringed? 24 Creation stories 11 Fair dealings provisions 24 © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Recording oral stories 11 -

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

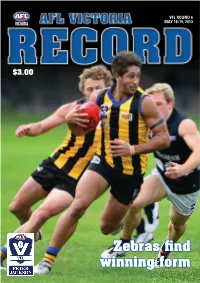

VFL Record Rnd 6.Indd

VFL ROUND 6 MAY 18-19, 2013 $3.00 ZZebrasebras fi nndd wwinninginning fformorm WWAFLAFL 117.16.1187.16.118 d VVFLFL 115.11.1015.11.101 Give exit fees the boot. And lock-in contracts the hip and shoulder. AlintaAlinta EnerEnergy’sgy’s Fair GGoo 1155 • NoNo lock-inlock-in contractscontracts • No exitexit fees • 15%15% off your electricity usageusage* forfor as lonlongg as you continue to be on this planplan 18001800 46 2525 4646 alintaenergy.com.aualintaenergy.com.au *15% off your electricity usage based on Alinta Energy’s published Standing Tariffs for Victoria. Terms and conditionsconditions apply.apply. NNotot avaavailableilable wwithith sosolar.lar. EDITORIAL State football CONGRATULATIONS to the West Australian Football League for its victory against the Peter Jackson VFL last Saturday at Northam. The host State emerged from a typically hard fought State player, as well as to Wayde match with a 17-point win after grabbing the lead midway Twomey, who won the WAFL’s through the last quarter. Simpson Medal. Full credit to both teams for the manner in which they What was particularly pleasing played; the game showcased the high standard and quality was the opportunity afforded to so many players to play football that exists in the respective State Leagues. State representative football for the fi rst time. There were One would suspect that a number of players from the game just four players returning to the Peter Jackson VFL team will come under the scrutiny of AFL recruiters come the end that defeated Tasmania last year. of the year. Last year’s Peter Jackson VFL team contained And, the average age of the Peter Jackson VFL team of 24 six players who are now on an AFL list. -

BENDIGO BOMBERS Coach: ADRIAN HICKMOTT

VFL squads CAPTAIN: JAMES FLAHERTY BENDIGO BOMBERS Coach: ADRIAN HICKMOTT No. Name DOB HT WT Previous clubs G B 1 Jay Neagle * 17/01/88 191 100 gippsland Power/Traralgon 2 Ricky DysoN * 28/09/85 182 82 Northern Knights/epping 3 Paul scaNloN 19/10/77 178 85 seymour/ Northern Bullants (VFl) 4 simon DaVies 30/09/89 176 78 North shore 5 stewart CrameRi 10/08/88 187 95 maryborough 6 Josh Bowe 25/06/87 176 79 Bendigo Pioneers/eaglehawk 7 leroy Jetta * 06/07/88 178 75 south Fremantle (WA) 9 Brent PRismall * 14/07/86 186 82 geelong/western Jets/werribee 10 Blair Holmes 18/05/89 176 80 Bendigo Pioneers/sandhurst 11 David ZaHaRaKis * 21/02/90 182 76 Northern Knights/marcellin college/eltham 12 michael HuRley * 01/06/90 193 91 Northern Knights/macleod 13 Darren Hulme 19/07/77 170 78 clayton/carlton 14 sam loNeRgaN * 26/03/87 182 80 Tasmania (VFl)/launceston 15 Joel maloNe 10/01/84 176 80 maryborough 16 Tayte PeaRs * 24/03/90 191 91 east Perth (WA) 17 Jay NasH * 21/12/85 188 84 central District (SA) 18 simon weeKley 19/03/87 187 88 sea lake/sandhurst 19 James BRisTow 29/01/89 194 101 gippsland Power/sale 20 charles slatteRy 16/01/84 183 81 central District (SA) 21 Hayden SkiPworth * 25/02/83 177 78 Bendigo Bombers (VFl)/adelaide 22 James FlaHerty 05/11/86 188 87 south Bendigo 23 David myeRs * 30/06/89 190 85 Perth (WA) 24 John williams * 08/10/88 188 84 morningside (Qld) 25 Brent ChaPmaN 31/03/83 183 76 Barooga 26 cale HooKeR * 13/10/88 196 93 east Fremantle (WA) 27 Jason laycocK * 04/11/84 201 103 Tassie mariners/east Devonport 28 Darcy DaNiHeR * -

RECONCILIATION ACTION PLAN May 2015 to May 2017

WEST COAST EAGLES FOOTBALL CLUB AND WIRRPANDA FOUNDATION RECONCILIATION ACTION PLAN May 2015 to May 2017 1 2 “My name is Josh Hill. I was born and bred “I am a proud Noongar person, with strong in WA and play football for the West Coast cultural beliefs that were passed on to me Eagles. I’m 26 years old and proud to be a by my father and grandparents. I am a past member of two Indigenous tribes, namely player of the West Coast Eagles Football Club the Noongar and Bardi tribes. I’m very proud and currently employed at the club as an of my culture. We have faced tough times Indigenous Liaison Officer. The West Coast in the past, but still manage to stand strong Eagles Football Club’s Reconciliation Action together and fight racism, discrimination and Plan outlines the club’s actions and outcomes, which will strengthen inequality. The club’s development of a Reconciliation Action Plan will their relationships and gain respect with the Aboriginal and Torres be amazing in demonstrating respect for our culture and helping create Strait Islander peoples. I personally will support the West Coast Eagles opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The Football Club and will assist the club to understand our cultural ways to opportunities will help drive and motivate those in need to push for a achieve the positive outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander better future. A lot of people out there don’t get the opportunities and peoples. We need to walk the pathway through the West Coast Eagles I personally will be helping as much as possible to mentor those in need gateway together as ONE. -

DAVID WILLIAMSON Is Australia's Best Known and Most Widely

DAVID WILLIAMSON is Australia’s best known and most widely performed playwright. His first full-length play The Coming of Stork was presented at La Mama Theatre in 1970 and was followed by The Removalists and Don’s Party in 1971. His prodigious output since then includes The Department, The Club, Travelling North, The Perfectionist, Sons of Cain, Emerald City, Top Silk, Money and Friends, Brilliant Lies, Sanctuary, Dead White Males, After the Ball, Corporate Vibes, Face to Face, The Great Man, Up For Grabs, A Conversation, Charitable Intent, Soulmates, Birthrights, Amigos, Flatfoot, Operator, Influence, Lotte’s Gift, Scarlet O’Hara at the Crimson Parrot, Let the Sunshine and Rhinestone Rex and Miss Monica, Nothing Personal and Don Parties On, a sequel to Don’s Party, When Dad Married Fury, At Any Cost?, co-written with Mohamed Khadra, Dream Home, Happiness, Cruise Control and Jack of Hearts. His plays have been translated into many languages and performed internationally, including major productions in London, Los Angeles, New York and Washington. Dead White Males completed a successful UK production in 1999. Up For Grabs went on to a West End production starring Madonna in the lead role. In 2008 Scarlet O’Hara at the Crimson Parrot premiered at the Melbourne Theatre Company starring Caroline O’Connor and directed by Simon Phillips. As a screenwriter, David has brought to the screen his own plays including The Removalists, Don’s Party, The Club, Travelling North and Emerald City along with his original screenplays for feature films including Libido, Petersen, Gallipoli, Phar Lap, The Year of Living Dangerously and Balibo. -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Australia Council Nationhood, National Identity and Democracy

AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS SUBMISSION NATIONHOOD, NATIONAL IDENTITY AND DEMOCRACY INQUIRY October 2019 1 CONTENTS Contents 2 About the Australia Council 3 Executive summary 4 Submission 6 Our arts shape and communicate our cultural identity 6 First Nations arts are central to understanding who we are as Australians 7 Our diverse artistic expression is reshaping our contemporary national identity 9 Our creative expressions are an antidote to declining public trust and social divisions 13 Conclusion 14 Policy options 15 2 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL The Australia Council is the Australian Government’s principal arts funding and advisory body. We champion and invest in Australian arts and creativity. We support all facets of the creative process and are committed to ensuring all Australians can experience the benefits of the arts and feel part of the cultural life of this nation. The Australia Council’s investment in arts and creativity presents a vital opportunity to develop Australia’s identity and reputation as a sophisticated and creative nation with a confident, connected community. Australia’s arts and creativity are among our nation’s most powerful assets, delivering substantial public value across portfolios: investing in the arts is investing in the social, economic and cultural success of our nation. For half a century the Australia Council has invested in activity that directly and powerfully contributes to Australia’s cultural identity and social cohesion. Our vision Creativity Connects Us1 is underpinned by five strategic objectives: • More Australians are transformed by arts experiences • Our arts reflect us • First Nations arts and culture are cherished • Arts and creativity are thriving • Arts and creativity are valued. -

Week9 E-Record .Indd

E-Footy RECORD 31st May 2008 Issue 9 Editorial with Marty King AFL AND AFLPA SET TO MOVE ON NEW ALCOHOL POLICY It’s terrifi c to see the AFL and the AFL Players Association working collaboratively to formulate a new policy on responsible alcohol consumption in the football environment. They are seeking feedback from each of the 16 AFL clubs, together with key national drug and alcohol experts, before framing a policy with guidelines that all AFL clubs and associated bod- ies like AFL Queensland can use to develop their own. This comes after a lot of background work was done over almost two years and the AFL Com- mission received a full briefi ng. The AFL, the Players’ Association and the AFL clubs understand that quite clearly that they have a responsibility to promote responsible drinking within the AFL and among the 16 clubs, the players and staff. But it’s not just about the elite level. The same will apply at the grassroots level and we at AFLQ will look to partner with the League on this important initiative. The guidelines within the AFL Framing Policy will provide a framework for AFL clubs and asso- ciated bodies to assist them in developing their own individual club responsible alcohol policies. The AFL Framing Policy lists a set of objectives for players and club staff, including the devel- opment of approaches for responsible consumption, effective pathways for treatment of alco- hol-related problems, creating responsible drinking cultures and using player welfare oriented and education-based approaches to promote responsible alcohol consumption. -

Annual Report

2013-14 ANNUAL REPORT Contents President’s Report 2 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 6 Message from the Australian Sports Commission 8 High Performance 10 Competitions 14 Participation 16 Communications & Marketing 20 Board and Committees 22 Committees & Commissions 26 Summary of the Financial Report 30 Financial Report Directors’ Report 33 Auditors Independence Declaration 39 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 40 Statement of Financial Position 41 Statement of Changes in Equity 42 Statement of Cash Flows 43 Notes to the Financial Statements 44 Directors’ Declaration 57 Independent Auditor’s Report 58 Participation Figures 60 Athletics ACT 62 Athletics New South Wales 66 Athletics Northern Territory 70 Queensland Athletics 72 Athletics South Australia 74 Athletics Tasmania 76 Athletics Victoria 78 Athletics Western Australia 80 Vale 82 Australian Records 86 Life Members & Award Winners 88 Athletics Australia Board of Directors & Staff 96 Athletics Australia Annual Report 2013-14 1 President’s Report It is my pleasure to present the Annual Report for State and Territory Sport Institutes and Academies. Athletics Australia for the 2013/2014 financial The contribution of the Federal and State year. The Board of Athletics Australia appointed Governments to the establishment and running of me as President and Chairman in November Lakeside Stadium and Athletics House is gratefully 2013, succeeding Rob Fildes OAM who had acknowledged. served 8 distinguished years as President. Rob gave outstanding service to the sport of Athletics Australia continues to work closely with athletics and I congratulate him on his overall the Australian Sports Commission (ASC) who performance. It is certainly the case that athletics provides expert advice in relation to governance in Australia is in a much stronger position as a and leadership. -

Australia Chapter in the Sports Law Review

the Sports Law Review Law Sports Sports Law Review Fifth Edition Editor András Gurovits Fifth Edition Fifth lawreviews © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd Sports Law Review Fifth Edition Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd This article was first published in December 2019 For further information please contact [email protected] Editor András Gurovits lawreviews © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd PUBLISHER Tom Barnes SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Joel Woods SENIOR ACCOUNT MANAGERS Pere Aspinall, Jack Bagnall ACCOUNT MANAGERS Olivia Budd, Katie Hodgetts, Reece Whelan PRODUCT MARKETING EXECUTIVE Rebecca Mogridge RESEARCH LEAD Kieran Hansen EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Tommy Lawson HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Helen Smith SUBEDITOR Janina Godowska CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Nick Brailey Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London Meridian House, 34-35 Farringdon Street, London, EC2A 4HL, UK © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided was accurate as at November 2019, be advised -

Mckee, Alan (1996) Making Race Mean : the Limits of Interpretation in the Case of Australian Aboriginality in Films and Television Programs

McKee, Alan (1996) Making race mean : the limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4783/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Making Race Mean The limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs by Alan McKee (M.A.Hons.) Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow March 1996 Page 2 Abstract Academic work on Aboriginality in popular media has, understandably, been largely written in defensive registers. Aware of horrendous histories of Aboriginal murder, dispossession and pitying understanding at the hands of settlers, writers are worried about the effects of raced representation; and are always concerned to identify those texts which might be labelled racist. In order to make such a search meaningful, though, it is necessary to take as axiomatic certain propositions about the functioning of films: that they 'mean' in particular and stable ways, for example; and that sophisticated reading strategies can fully account for the possible ways a film interacts with audiences.