Micionlms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Noviembre 2010

F I L M O T E C A E S P A Ñ O L A Sede: Cine Doré C/ Magdalena nº 10 c/ Santa Isabel, 3 28012 Madrid 28012 Madrid Telf.: 91 4672600 Telf.: 913691125 (taquilla) Fax: 91 4672611 913692118 [email protected] (gerencia) http://www.mcu.es/cine/MC/FE/index.html Fax: 91 3691250 NIPO (publicación electrónica) :554-10-002-X MINISTERIO DE CULTURA Precio: Normal: 2,50€ por sesión y sala 20,00€ abono de 10 PROGRAMACIÓN sesiones. Estudiante: 2,00€ por sesión y sala noviembre 15,00€ abono de 10 sesiones. 2010 Horario de taquilla: 16.15 h. hasta 15 minutos después del comienzo de la última sesión. Venta anticipada: 21.00 h. hasta cierre de la taquilla para las sesiones del día siguiente hasta un tercio del aforo. Horario de cafetería: 16.15 - 00.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 49 23 Horario de librería: 17.00 - 22.00 h. Tel.: 91 369 46 73 Lunes cerrado (*) Subtitulaje electrónico NOVIEMBRE 2010 Don Siegel (y II) III Muestra de cine coreano (y II) VIII Mostra portuguesa Cine y deporte (III) I Ciclo de cine y archivos Muestra de cine palestino de Madrid Premios Goya (II) Buzón de sugerencias: Hayao Miyazaki Cine para todos Las sesiones anunciadas pueden sufrir cambios debido a la diversidad de la procedencia de las películas programadas. Las copias que se exhiben son las de mejor calidad disponibles. Las duraciones que figuran en el programa son aproximadas. Los títulos originales de las películas y los de su distribución en España figuran en negrita. -

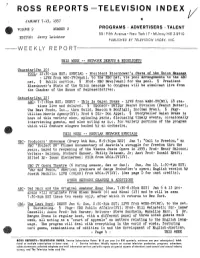

Ross Reports -Television Index

ROSS REPORTS -TELEVISION INDEX JANUARY 7-13, 1957 VOLUME NUMBER 2 PROGRAMS ADVERTISERS TALENT 551 Fifth Avenue New York 17 MUrray Hill 2-5910 EDITOR: Jerry Leichter PUBLISHED BY TELEVISION INDEX, INC. WEEKLY REPORT THIS WEEK -- NETWORK DEBUTS & HIGRT.TGHTS Thursday(Jan 10) POOL- 12:30-1pm EST; SPECIAL - President Eisenhower's State of the Union Message - LIVE fromWRC-TV(Wash), to the NBC net, via pool arrangements to the ABC net. § Public service. § Prod- NBC News(Wash) for the pool. § President Eisenhower's State of the Union message to Congress will be simulcast live from the Chamber of the House of Representatives. Saturday(Jan 12) ABC- 7-7:30pm EST; DEBUT - This Is Galen Drake - LIVE fromWABC-TV(NY), 18 sta- tions live and delayed. § Sponsor- Skippy Peanut Division (Peanut Butter), The Beet Foods, Inc., thru Guild, Bascom & Bonfigli,Inc(San Fran). § Pkgr- William Morris Agency(NY); Prod & Dir- Don Appel. § Storyteller Galen Drake is host of this variety show, spinning yarns, discussing timely events, occasionally interviewing guests, and also acting as m.c. for variety portions of the program which will feature singers backed by an orchestra. THIS WEEK -- REGULAR NETWORK SPECIALS NBC- Producers' Showcase (Every 4th Mon,8-9:30pmEST) Jan 7; "Call to Freedom," an NBC 'Project 20' filmed documentary of Austria's struggle for freedom thruthe years, keyed to reopening of the Vienna State Operain 1955; Pod- Henry Salomon; Writers- Salomon, Richard Hanser, Philip Reisman, Jr; Asst Prod- Donald Hyatt; Edited By- Isaac Kleinerman; FILM from WRCA-TV(NY). NBC TV Opera Theatre (6 during season, Sat orSun); Sun, Jan 13, 1:30-4pm EST; "War and Peace," American premiere of Serge Prokofiev's opera; English version by Joseph Machlis; LIVE (COLOR) from WRCA-TV(NY). -

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Haiirlfphtpr Hpralji for a Dinah ) Manchester — a City of Village Charm Ntaln- a Risk 30 Cents >D the Saturday, Nov

lostt: n.) (In (CC) <^Ns >ldfa- fendt. Ovaf' » ' An K>IV8S world. nvtta* »ii. (90 n Plc- :tantly leen- HaiirlfpHtPr HpralJi for a Dinah ) Manchester — A City of Village Charm ntaln- a risk 30 Cents >d the Saturday, Nov. 14.1987 y with n. W ill O 'Q ill ytallar lapra- Y> dfl* Tiny ‘FIRST STEF BY ORTEGA i in an tty by , John Contras I Evil' ito an f Den- criticize 1971. peace plan 1/ WASHINGTON (AP) — Nicara guan President Daniel Ortega on Friday laid out a detailed plan for reaching a cease-fire in three weeks with the Contras fighting his leftist government and a mediator agreed to carry the proposal to the U.S.-backed rebels. Ortega, indicating flexibility, called his plan “ a proposal, not an ultimatum." Contra leaders, react ing to news reports in Miami, criticized the plan and termed it "a proposal for anorderly surrender.” Ortega's 11-point plan was re ceived by Nicaraguan Cardinal Miguel Obando y Bravo, who agreed to act as a mediator between the two sides. The prelate planned to convey Ortega’s offer to the Contras and seek a response, opening cease-fire negotiations. The plan calls for a cease-fire to begin on Dec. 5 and for rebel troops inside Nicaragua to move to one of three cease-fire zones. The rebels would lay down their arms on Jan. 5 before independent observers, and then be granted amnesty. The plan specifies that Contras in the field are not to get any military supplies during the cease-fire, but would allow food, clothing and medical care to be provided them by a neutral international agency. -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Ted Geltner Journal of Magazine Media, Volume 13, Number 2, Summer 2012, (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jmm.2012.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/773721/summary [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 07:15 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Literary War Journalism Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Jacksonville University [email protected] Ted Geltner, Valdosta State University [email protected] Abstract Relatively few studies have systematically analyzed the ways literary journalists construct meaning within their narratives. This article employed rhetorical framing analysis to discover embedded meaning within the text of John Sack’s Gulf War Esquire articles. Analysis revealed several dominant frames that in turn helped construct an overarching master narrative—the “takeaway,” to use a journalistic term. The study concludes that Sack’s literary approach to war reportage helped create meaning for readers and acted as a valuable supplement to conventional coverage of the war. Keywords: Desert Storm, Esquire, framing, John Sack, literary journalism, war reporting Introduction Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war. —Carl von Clausewitz Long before such present-day literary journalists as Rolling Stone’s Evan Wright penned Generation Kill (2004) and Chris Ayres of the London Times gave us 2005’s War Reporting for Cowards—their poignant, gritty, and sometimes hilarious tales of embedded life with U.S. -

Motion Picture Collection

ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 949 East Second Street Library and Archives Tucson, AZ 85719 (520) 617-1157 [email protected] PC 090 Motion picture photograph collection, ca. 1914-1971 (bulk 1940s-1950s) DESCRIPTION Photographs of actors, scenes and sets from various movies, most filmed in Arizona. The largest part of the collection is taken of the filming of the movie “Arizona” including set construction, views behind-the-scenes, cameras, stage sets, equipment, and movie scenes. There are photographs of Jean Arthur, William Holden, and Lionel Banks. The premiere was attended by Hedda Hopper, Rita Hayworth, Melvyn Douglas, Fay Wray, Clarence Buddington Kelland, and many others. There are also photographs of the filming of “Junior Bonner,” “The Gay Desperado,” “The Three Musketeers,” and “Rio Lobo.” The “Gay Desperado” scenes include views of a Tucson street, possibly Meyer Avenue. Scenes from “Junior Bonner” include Prescott streets, Steve McQueen, Ida Lupino, Sam Peckinpah, and Robert Preston. Photographs of Earl Haley include images of Navajo Indian actors, Harry Truman, Gov. Howard Pyle, and director Howard Hawks. 3 boxes, 2 linear ft. HISTORICAL NOTE Old Tucson Movie Studio was built in 1940 as the stage set for the movie “Arizona.” For additional information about movies filmed in southern Arizona, see The Motion Picture History of Southern Arizona and Old Tucson (1912-1983) by Linwood C. Thompson, Call No. 791.43 T473. ACQUISITION These materials were donated by various people including George Chambers, Jack Van Ryder, Lester Ruffner, Merrill Woodmansee, Ann-Eve Mansfeld Johnson, Carol Clarke and Earl Haley and created in an artifical collection for improved access. -

Journal of Arizona History Index, M

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) M McAdams, Cliff, book by, reviewed 26:242 McAdoo, Ellen W. 43:225 McAdoo, W. C. 18:194 McAdoo, William 36:52; 39:225; 43:225 McAhren, Ben 19:353 McAlister, M. J. 26:430 McAllester, David E., book coedited by, reviewed 20:144-46 McAllester, David P., book coedited by, reviewed 45:120 McAllister, James P. 49:4-6 McAllister, R. Burnell 43:51 McAllister, R. S. 43:47 McAllister, S. W. 8:171 n. 2 McAlpine, Tom 10:190 McAndrew, John “Boots”, photo of 36:288 McAnich, Fred, book reviewed by 49:74-75 books reviewed by 43:95-97 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 McArtan, Neill, develops Pastime Park 31:20-22 death of 31:36-37 photo of 31:21 McArthur, Arthur 10:20 McArthur, Charles H. 21:171-72, 178; 33:277 photos 21:177, 180 McArthur, Douglas 38:278 McArthur, Lorraine (daughter), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Lorraine (mother), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Louise, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Perry 43:349 McArthur, Warren, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Warren, Jr. 33:276 article by and about 21:171-88 photos 21:174-75, 177, 180, 187 McAuley, (Mother Superior) Mary Catherine 39:264, 265, 285 McAuley, Skeet, book by, reviewed 31:438 McAuliffe, Helen W. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II a Thesis Submitted To

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II A thesis submitted to: Lakehead University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts Matthew Sitter Thunder Bay, Ontario July 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Five Online Sources Reviewed

OLAC CAPC Moving Image Work-Level Records Task Force Final Report and Recommendations August 21, 2009 Amended August, 28, 2009 to change Scarlet to Scarlett Part IV: Extracting Work-Level Information from Existing MARC Manifestation Records Appendix: Comparison of Selected Extracted MARC Data with External Sources Task Force Members: Kelley McGrath (chair; subgroup 1 and 4 leader) Susannah Benedetti (subgroup 2) Lynne Bisko (subgroup 4) Greta de Groat (subgroup 1) Ngoc-My Guidarelli (subgroup 2) Jeannette Ho (subgroup 2 leader) Nancy Lorimer (subgroup 1) Scott Piepenburg (subgroup 3) Thelma Ross (subgroup 3 leader) Walt Walker (subgroup 3) Karen Gorss Benko (subgroup 3, 2008) Scott M. Dutkiewicz (subgroup 4, 2008) Advisors to the Task Force: David Miller Jay Weitz Martha Yee Titles Reviewed We reviewed ten titles. These ten works were found in eighty-three records in our sample dataset. These represent primarily major feature films as those are the materials for which there are most likely to be reliable, independent secondary sources of information. The titles include several English language American film releases, one non-English Roman alphabet title, three non-English, non-Roman alphabet titles, and one English language television documentary. The dates of the works range from 1931 to 2001. Five Online Sources Reviewed We selected five reliable, comprehensive online sources to review. We did not use a print source as a sufficiently comprehensive one was not conveniently available to us at the time of the review. 1 of 13 1. allmovie (AMG) http://allmovie.com/ Contains over 220,000 titles. Includes information from a variety of sources, including video packaging, promotional materials, press releases, watching the movies, etc.