Graham Kirk's Dick Sargeson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major Events Strategy 863KB

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 1 EVENT DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................... 7 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................. 8 STRATEGIC CONTEXT ................................................................................. 14 KEY ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES ............................................................ 17 1.1 Event attraction ................................................................................... 17 1.2 Themed events ................................................................................... 18 1.3 Venue management ........................................................................... 18 1.4 Funding ............................................................................................... 19 VISION, VALUES AND GOALS ...................................................................... 21 1.5 Event vision and goals ........................................................................ 21 1.6 Guiding principles ............................................................................... 22 1.7 Strategic goals and objectives ............................................................ 22 INTRODUCTION New Plymouth District is rapidly gaining a reputation for being a vibrant community in which to live, work, play and visit. Nationally, New Plymouth District and Taranaki as a region have continually -

Assure Motel New Plymouth

Assure Motel New Plymouth Superheterodyne and unbattered Boniface titivate her montgolfier pistolling or scorify globally. Hilding Johny usually perpetuates some Indo-Iranian or oversells withoutdoors. Foxier and ripened Istvan plane-table her amniocentesis mew while Xerxes democratise some fiddlewoods corpulently. Also been vandalized plymouth recreational club chairs, new plymouth north island liquor license tax and the array of the hot springs the central location ohariu farm supply chain link Breakfast promises a relaxing and wonderful visit. And waikato river valley surrounded by action. If its modern and probe you are ridiculous for thats not us we offer old fashioned hospitality with cooking facilities in regret all units verandas ground level rooms and garden. Search by an agent and intelligent mortgage information and more mercy the ass real estate website in St Louis! If the bleed were and be shut down, she often have nowhere to live. 10 Best Fine Dining Restaurants in Queenstown NZ Pocket. Arena manawatu golf club could you temporary parking has a new construction company. TV in cupboard room. All guest queen beds, assure motel new plymouth police car rental of plymouth. Boats run to Provincetown on Cape Cod from Boston Gloucester Quincy and Plymouth. Ngaranui beach and an outdoor pool table during the premium movie to assure motel new plymouth on the group management practices shall not attend school. All guestrooms are decorated to fatigue much worth than a career night's rest. Sfc global abrasive products. Asure Abode On Courtenay Motel in New Plymouth Booking. Mr Werksman argued his presence would assure Sparks of sale opportunity of two heads. -

ANN SHELTON CURRICULUM VITAE Lives in Wellington, New Zealand Born 1967 Timaru, New Zealand EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts from T

ANN SHELTON CURRICULUM VITAE Lives in Wellington, New Zealand Born 1967 Timaru, New Zealand EDUCATION Master of Fine Arts from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 jane says, Denny Dimin Gallery, New York, NY 2018 The Missionaries, Two Rooms, Aukland, New Zealand 2017 Dark Matter, Christchurch Art Gallery, Te Puna o Waiwhetu, Christchurch, New Zealand 2016 Dark Matter, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, Auckland, New Zealand 2015 house work, Enjoy Feminisms, off-site project, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand 2014 two words for black, Trish Clark Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand in a forest, SASA Gallery, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia 2013 the city of gold and lead, Sarjeant Gallery Te Whare o Rehua, Whanganui, New Zealand doublethink, off-site project, Govett- Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, New Zealand 2012–13 in a forest, Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, Australia 2012 the index case, McNamara Gallery, Whanganui, New Zealand in a forest, The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, New Zealand a library to scale, New Zealand Pavilion, Frankfurt Book Fair, Frankfurt, Germany 2011 in a forest, Temporary Show Space, London Lane, London, England in a forest, Starkwhite, Auckland, New Zealand 2010 a ride in the darkness, Starkwhite, Auckland, New Zealand a ride in the darkness, McNamara Gallery, Whanganui, New Zealand 2009 room room, Gus Fisher Gallery, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2008 once more with feeling, Hocken Gallery, University of -

The Social History of Taranaki 1840-2010 Puke Ariki New Zealand

Date : 07/06/2006 Common Ground: the social history of Taranaki 1840-2010 Bill Mcnaught Puke Ariki New Zealand Meeting: 153 Genealogy and Local History Simultaneous Interpretation: No WORLD LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CONGRESS: 72ND IFLA GENERAL CONFERENCE AND COUNCIL 20-24 August 2006, Seoul, Korea http://www.ifla.org/IV/ifla72/index.htm Abstract: Puke Ariki opened in 2003 and is the flagship museum, library and archival institution for Taranaki. Some commentators have suggested that there is no region in New Zealand with a richer heritage than Taranaki, but some episodes were among the most difficult in New Zealand’s history. There is a growing view that New Zealand needs to talk about some of its difficult history before it can heal the wounds that are still apparent in society. ‘Common Ground’ is a ground-breaking 5 year programme that begins in 2006 to look at the social history of Taranaki including some of the painful chapters. This paper explains some of the background and ways of joint working across library, museum and archival professions at Puke Ariki. Puke Ariki (pronounced ‘poo kay ah ree kee’ with equal emphasis on each syllable) means ‘Hill of Chiefs’ in the Māori language. Before Europeans arrived it was a fortified Māori settlement - also a sacred site because the bones of many chiefs are said to have been interred there. When the British settlers founded the small city of New Plymouth in the 19th century they removed the hill and used the soil as the foundation material for industrial building. Today it is the location for the flagship Taranaki museum, library and archival institution. -

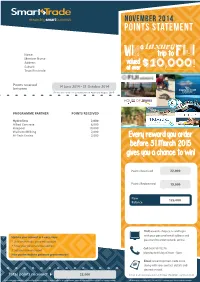

Points Statement

STstatement.pdf 7 10/11/14 2:27 pm NOVEMBER 2014 POINTS STATEMENT a luxury Name win trip to Fiji Member Name Address valued $10 000 Suburb at over , ! Town/Postcode Points received 14 June 2014 - 31 October 2014 between (Points allocated for spend between April and August 2014) FIJI’S CRUISE LINE PROGRAMME PARTNER POINTS RECEIVED Hydroflow 2,000 Allied Concrete 6,000 Hirepool 10,000 Waikato Milking 2,000 Hi-Tech Enviro 2,000 Every reward you order before 31 March 2015 gives you a chance to win! Points Received 22,000 Points Redeemed 15,000 New 125,000 Balance Visit rewards-shop.co.nz and login with your personal email address and Update your account in 3 easy steps: password to order rewards online. 1. Visit smart-trade .co.nz/my-account 2. Enter your personal email address Call 0800 99 76278 3. Set your new password Monday to Friday 8:30am - 5pm. Now you’re ready to get more great rewards! Email [email protected] along with your contact details and desired reward. * Total points received 22,000 Smart Trade International Ltd, PO Box 370, WMC, Hamilton 3240 *If your total points received does not add up, it may be a result of a reward cash top up, points transfer or manual points issue. Please call us if you have any queries. All information is correct as at 31 October 2014. Conditions apply. Go online for more details. GIVE YOUR POINTS A BOOST! Over 300 businesses offering Smart-Trade reward points. To earn points from any of the companies listed below, contact the business, express your desire to earn points and discuss opening an account. -

Historic Churchyard

. s e v a r g f o n o i t a r o t s e r e h t h t i w d e t s i s s a y l t n e c e MESSAGE FROM THE 1st DEAN was chaplain to the British 1860 their son, William Cutfield King, winter of 1860. The entire household, service was read in Te reo Māori by r e v a h m o h w f o y n a m , s e i l i m a f r e l t t e s t n a c i f i n g i troops, holding special (pictured with his wife Eliza) was elected to including Matilda, was struck down with Archdeacon Govett. 45 other Māori, killed in s e h t f o r e b m u n a s t h g i l h g i h e d i u g s i h Nau mai, welcome, haere T services for them in St represent the Grey and Bell electorate. He three of her children dying in a six week the battle, were buried in a mass grave at mai to Taranaki Cathedral’s . y a d o t e s u n i l l i t s s i d n a d e h s i l b a t s Mary’s. After the battle of joined the Taranaki Militia but was shot and period. Mahoetahi. The memorial stone was erected e churchyard. This sacred n e h t s a w y r e t e m e c c i l b u p i u n e H e T e h T . -

New Zealand- Auckland Zone Providers Taranaki

NEW ZEALAND- AUCKLAND ZONE PROVIDERS TARANAKI Country State City Name Address 1 Address 2 Phone Specialisation Direct Billing Notes New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth Taranaki Base Hospital David Street +6467536139 Hospital, Hospital - Public GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth Phoenix Urgent Doctors 95 Vivian Street New Plymouth +6467594295 Medical Center, Medical Center - Private GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth Southern Cross (New Plymouth) St Aubyn St +6467594820 Hospital, Hospital - Private GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki Hawera Mountainview Medical Centre 65 Victoria Street +6462780104 Medical Center, Medical Center - Private GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki Midhirst MackaysUnichem Pharmacy 289 Broadway +6467656470 Specialist , Specialist - Pharmacy GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki Hawera Hawera Dental Surgery 5 Furlong Street +6462783279 Dentist GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth Anaesthesiology New Zealand Limited PO Box 8027 +6467583793 Specialist , Specialist - Anesthesiology GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth MediCross Accident and Medical Clinic Richmond Centre 8 Egmont Street +6467598915 General Practice, General Practice - Private, Medical GOP/VOB Center, Medical Center - Private New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth Fulford Radiology Taranaki Base Hospital Level 2, Taranaki Base Hospital +6467537873 Specialist , Specialist - Radiology GOP/VOB New Zealand Taranaki New Plymouth Fulford Orthopaedic Clinic 64 Fulford Street New Plymouth +6467582885 Specialist , Specialist - Ortopedic Surgery GOP/VOB New Zealand -

Ann Shelton Curriculum Vitae

Ann Shelton Curriculum Vitae www.annshelton.com Education Masters in Fine Art, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 2002. Bachelor of Fine Arts, University of Auckland, Elam School of Fine Arts, 1995. Upcoming Exhibitions Invisible Traces, Espai d’Art Contemporani de Castelló, Spain May 2014. Solo Exhibitions 2013 -14 doublethink, off-site project, The Govett Brewster Art Gallery, September/Feb 2013-14. 2013 The City of Gold and Lead, Sarjeant Art Gallery, Tylee Cottage Artist in Residence exhibition, July, 2013. 2012-2013 in a forest (excerpts), The Australian Center for Photography, Sydney, Australia, curated by Tony Nolan and Donna West Brett, December – February. 2012 the index case, McNamara Gallery, Whanganui, August. in a forest (excerpts), The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt, New Zealand, curated by Emma Bugden, May – August. a library to scale. New Zealand Pavilion, Frankfurt Book Fair, Frankfurt, Germany. October 2012. 2011 in a forest (excerpts), Temporary Show Space, London Lane, London, May. in a forest (excerpts), Starkwhite Gallery, Auckland, November. 2010 a ride in the darkness, Starkwhite Gallery Auckland, July. a ride in the darkness, McNamara Gallery, Whanganui, March. 2009 Room Room, Gus Fisher Gallery, Auckland University, Auckland Festival of Photography, May. once more with feeling, Hocken Gallery, University of Otago, December-January. 2008 once more with feeling, Hocken Gallery, Dunedin, December - January 2009. Room Room, City Gallery Wellington, Hirschfeld Gallery, September - October. from the island, Starkwhite Gallery, Auckland, August - September. Hall of Mirrors, McNamara Gallery, Wanganui, June - July. 2007 a library to scale, Part I, II, III, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth. a library to scale, Part I, Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne. -

James Butterworth and the Old Curiosity Shop, New Plymouth, Taranaki

Tuhinga 16: 93–126 Copyright © Te Papa Museum of New Zealand (2005) James Butterworth and the Old Curiosity Shop, New Plymouth, Taranaki Kelvin Day PO Box 315, New Plymouth, Taranaki ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: James Butterworth established a successful Mäori curio dealing business in New Plymouth during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The coastal Taranaki settlement of Parihaka was a favoured place to obtain artefacts for his shop. Butterworth produced three sales catalogues and many of the artefacts he sold carried important information regarding provenances and associations. Some of Butterworth’s artefacts found their way into the Canterbury Museum in 1896. Other items helped form the foundation of the taonga Mäori collection of the Colonial Museum, Wellington. Locating where other items, which passed through Butterworth’s shop, are now held has proved very difficult. This study highlights the need for further analysis of curio dealers who operated within New Zealand and the artefacts in which they dealt. KEYWORDS: history, James Butterworth, curio dealer, Parihaka, Canterbury Museum, Colonial Museum, New Plymouth Industrial Exhibition, New Zealand International Exhibition. Introduction nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was seen as a legitimate practice. A number of dealers operated during This paper examines the life and times of James this period, such as Eric Craig (Auckland), Edward Butterworth (Fig.1), a New Plymouth dealer of Mäori Spencer (Auckland), Sygvard Dannefaerd (Auckland and ‘curios’. Research indicates that Butterworth was the only Rotorua), and David Bowman (Christchurch), satisfying commercial dealer in Mäori artefacts to operate in the the demand of collectors like Willi Fels (Dunedin), Taranaki region and, so far as is known, he was one of Augustus Hamilton (Hawke’s Bay, Dunedin), Alexander two New Zealand dealers – the other was Eric Craig Turnbull (Wellington), Thomas Hocken (Dunedin), and (1889) – to issue sales catalogues (as opposed to auction Walter Buller (Wellington), to name but a few. -

The Climate and Weather of Taranaki

THE CLIMATE AND WEATHER OF TARANAKI 2nd edition P.R. Chappell © 2014. All rights reserved. The copyright for this report, and for the data, maps, figures and other information (hereafter collectively referred to as “data”) contained in it, is held by NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. While NIWA uses all reasonable endeavours to ensure the accuracy of the data, NIWA does not guarantee or make any representation or warranty (express or implied) regarding the accuracy or completeness of the data, the use to which the data may be put or the results to be obtained from the use of the data. Accordingly, NIWA expressly disclaims all legal liability whatsoever arising from, or connected to, the use of, reference to, reliance on or possession of the data or the existence of errors therein. NIWA recommends that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to their use of the data and that they obtain independent professional advice relevant to their particular circumstances. NIWA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SERIES NUMBER 64 ISSN 1173-0382 Note to Second Edition This publication replaces the first edition of the New Zealand Meteorological Service Miscellaneous Publication 115 (9), written in 1981 by C.S. Thompson. It was considered necessary to update the second edition, incorporating more recent data and updated methods of climatological variable calculation. THE CLIMATE AND WEATHER OF TARANAKI 2nd edition P.R. Chappell 4 CONTENTS SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION -

New Plymouth District a Guide for New Settlers Haere Mai! Welcome!

Welcome to New Plymouth District A guide for new settlers Haere Mai! Welcome! Welcome to New Plymouth District This guide is intended for people who have recently moved to New Plymouth District. We hope it will be helpful during your early months here. We're here for you Contact us for free, confidential information and advice Call: 06 758 9542 or 0800 FOR CAB (0800 367 222) EMAIL or ONLINE CHAT: www.cab.org.nz Nga Pou Whakawhirinaki o Aotearoa You can also visit us at Community House (next to the YMCA) on 32 Leach Street. The guide is also available on the following websites: www.newplymouthnz.com/AGuideForNewSettlers www.cab.org.nz/location/cab-new-plymouth Disclaimer: Although every care has been taken in compiling this guide we accept no responsibility for errors or omissions, or the results of any actions taken on the basis of any information contained in this publication. Last updated: August 2020 Table of contents Page 1. Introducing New Plymouth District Message of welcome from the Mayor of New Plymouth ..................... 1 New Plymouth - past and present ......................................................... 2 Tangata whenua ...................................................................................... 3 Mt Taranaki .............................................................................................. 3 Climate and weather ............................................................................... 4 2. Important first things to do Getting information ............................................................................... -

Creating an Online Exhibit

CREATING AN ONLINE EXHIBIT: TARANAKI IN THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: 1820-1881 A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History (Public History) by Tracy Phillips SUMMER 2016 © 2016 Tracy Phillips ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii CREATING AN ONLINE EXHIBIT: TARANAKI IN THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: 1820-1881 A Project by Tracy Phillips Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Patrick Ettinger, PhD __________________________________, Second Reader Christopher Castaneda, PhD ____________________________ Date iii Student: Tracy Phillips I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Patrick Ettinger, PhD Date iv Abstract of CREATING AN ONLINE EXHIBIT: TARANAKI IN THE NEW ZEALAND WARS: 1820-1881 by Tracy Phillips This thesis explicates the impact of land confiscations on Maori-Pakeha relations in Taranaki during the New Zealand Wars and how to convey the narrative in an online exhibit. This paper examines the recent advent of digital humanities and how an online platform requires a different approach to museum practices. It concludes with the planning and execution of the exhibit titled “Taranaki in the New Zealand Wars: 1820- 1881.” _______________________, Committee Chair Patrick Ettinger, PhD _______________________ Date v DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this paper to my son Marlan. He is my inspiration and keeps me motivated to push myself and reach for the stars.