The Informer: February 2015 (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College English Honors Projects English Department 2012 Threnody Amy Fitzgerald Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Amy, "Threnody" (2012). English Honors Projects. Paper 21. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/english_honors/21 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threnody By Amy Fitzgerald English Department Honors Project, May 2012 Advisor: Peter Bognanni 1 Glossary of Words, Terms, and Institutions Commissie voor Oorlogspleegkinderen : Commission for War Foster Children; formed after World War II to relocate war orphans in the Netherlands, most of whom were Jewish (Dutch) Crèche : nursery (French origin) Fraulein : Miss (German) Hervormde Kweekschool : Reformed (religion) teacher’s training college Hollandsche Shouwberg : Dutch Theater Huppah : Jewish wedding canopy Kaddish : multipurpose Jewish prayer with several versions, including the Mourners’ Kaddish KP (full name Knokploeg): Assault Group, a Dutch resistance organization LO (full name Landelijke Organasatie voor Hulp aan Onderduikers): National Organization -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

April Newsletter

APRIL 2021 MCCO/MVRCL VOLUME 2, ISSUE 2 Newsletter Montgomery County Coroner’s Office & Miami Valley Regional Crime Lab A Message from Dr. Harshbarger The International Association of Coroners and Medical Inside This Issue Examiners (IACME) declared a week at the end of January as “National Medicolegal Death Investigator Week”. The role of a A Message from Dr. Harshbarger Medicolegal Death Investigator (MDI) is to investigate any death that falls under the jurisdiction of the medical examiner A Message from the Director or Coroner, including all suspicious, violent, unattended, Notable Visitors unexplained, and unexpected deaths. Also known as “Last Scientific Sections Responders”, the role they play in my office if crucial. Evidence Technician Class The service they provide is often overlooked and Morgue Musings underestimated. They are my eyes and ears on the scene and Meet the Staff throughout each death investigation. National Hat Day Please take a minute to appreciate and acknowledge the “Last Responders” in your office. MCCO/MVRCL Newsletter A Message from the Director of Operations BY BROOKE J. EHLERS Brooke J. Ehlers The COVID Pandemic: MCCO/MVRCL One Year Later Director of Last year around this time, the MCCO/MVRCL had just made the decision to split the employees into Operations shift work, schools were shutting down and struggling through distance learning plans, and toilet [email protected] paper had flown off the shelves in record numbers. Pure chaos! 937-225-6176 In the past year, we have adapted like Darwin himself was standing at our front door. Given the proper permissions and parameters, we learned to work remotely, communicate effectively, and conduct business virtually. -

Dual Enrollment

Georgia Military College 2020-2021 Catalog Contributing To Student Success! Stone Mountain Fairburn Fayetteville Madison Augusta Milledgeville Zebulon Sandersville Warner Robins Dublin Eastman Columbus Global Online College Valdosta www.gmc.edu Published by the Academic Affairs Administration Table of Contents WELCOME .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 13 A Letter from the President ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 A Letter from the Senior VP, Chief Academic Officer, and Dean of Faculty ........................................................................... 14 2020-2021 ACADEMIC CALENDAR ........................................................................................................................................................... 15 Four Term Calendar (MNC) ....................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Milledgeville Online (MLO) .................................................................................................................................................................. 15 Five Term Calendar (CMP) ....................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Governor's Guide to Homeland Security

A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION (NGA), founded in 1908, is the instrument through which the nation’s governors collectively influence the development and implementation of national policy and apply creative leadership to state issues. Its members are the governors of the 50 states, three territories and two commonwealths. The NGA Center for Best Practices is the nation’s only dedicated consulting firm for governors and their key policy staff. The NGA Center’s mission is to develop and implement innovative solutions to public policy challenges. Through the staff of the NGA Center, governors and their policy advisors can: • Quickly learn about what works, what doesn’t and what lessons can be learned from other governors grappling with the same problems; • Obtain specialized assistance in designing and implementing new programs or improving the effectiveness of current programs; • Receive up-to-date, comprehensive information about what is happening in other state capitals and in Washington, D.C., so governors are aware of cutting-edge policies; and • Learn about emerging national trends and their implications for states, so governors can prepare to meet future demands. For more information about NGA and the Center for Best Practices, please visit www.nga.org. A GOVERNOR’S GUIDE TO HOMELAND SECURITY NGA Center for Best Practices Homeland Security & Public Safety Division FEBRUARY 2019 Acknowledgements A Governor’s Guide to Homeland Security was produced by the Homeland Security & Public Safety Division of the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices (NGA Center) including Maggie Brunner, Reza Zomorrodian, David Forscey, Michael Garcia, Mary Catherine Ott, and Jeff McLeod. -

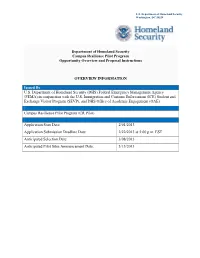

CR Pilot Program Announcement

U.S. Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 Department of Homeland Security Campus Resilience Pilot Program Opportunity Overview and Proposal Instructions OVERVIEW INFORMATION Issued By U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in conjunction with the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Student and Exchange Visitor Program (SEVP), and DHS Office of Academic Engagement (OAE). Opportunity Announcement Title Campus Resilience Pilot Program (CR Pilot) Key Dates and Time Application Start Date: 2/01/2013 Application Submission Deadline Date: 2/22/2013 at 5:00 p.m. EST Anticipated Selection Date: 3/08/2013 Anticipated Pilot Sites Announcement Date: 3/15/2013 DHS CAMPUS RESILIENCE PILOT PROGRAM PROPOSAL SUBMISSION PROCESS & ELIGIBILITY Opportunity Category Select the applicable opportunity category: Discretionary Mandatory Competitive Non-competitive Sole Source (Requires Awarding Office Pre-Approval and Explanation) CR Pilot sites will be selected based on evaluation criteria described in Section V. Proposal Submission Process Completed proposals should be emailed to [email protected] by 5:00 p.m. EST on Friday, February 22, 2013. Only electronic submissions will be accepted. Please reference “Campus Resilience Pilot Program” in the subject line. The file size limit is 5MB. Please submit in Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Word formats. An email acknowledgement of received submission will be sent upon receipt. Eligible Applicants The following entities are eligible to apply for participation in the CR Pilot: • Not-for-profit accredited public and state controlled institutions of higher education • Not-for-profit accredited private institutions of higher education Additional information should be provided under Full Announcement, Section III, Eligibility Criteria. -

Countering False Information on Social Media in Disasters and Emergencies, March 2018

Countering False Information on Social Media in Disasters and Emergencies Social Media Working Group for Emergency Services and Disaster Management March 2018 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 2 Motivations .................................................................................................................................... 4 Problem ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Causes and Spread ................................................................................................................... 6 Incorrect Information .............................................................................................................. 6 Insufficient Information ........................................................................................................... 7 Opportunistic Disinformation .................................................................................................. 8 Outdated Information ............................................................................................................. 8 Case Studies ............................................................................................................................... 10 -

Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025

TEXAS HOMELAND SECURITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2021-2025 LETTER FROM THE GOVERNOR Fellow Texans: Over the past five years, we have experienced a wide range of homeland security threats and hazards, from a global pandemic that threatens Texans’ health and economic well-being to the devastation of Hurricane Harvey and other natural disasters to the tragic mass shootings that claimed innocent lives in Sutherland Springs, Santa Fe, El Paso, and Midland-Odessa. We also recall the multi-site bombing campaign in Austin, the cybersecurity attack on over 20 local agencies, a border security crisis that overwhelmed federal capabilities, actual and threatened violence in our cities, and countless other incidents that tested the capabilities of our first responders and the resilience of our communities. In addition, Texas continues to see significant threats from international cartels, gangs, domestic terrorists, and cyber criminals. In this environment, it is essential that we actively assess and manage risks and work together as a team, with state and local governments, the private sector, and individuals, to enhance our preparedness and protect our communities. The Texas Homeland Security Strategic Plan 2021-2025 lays out Texas’ long-term vision to prevent and respond to attacks and disasters. It will serve as a guide in building, sustaining, and employing a wide variety of homeland security capabilities. As we build upon the state’s successes in implementing our homeland security strategy, we must be prepared to make adjustments based on changes in the threat landscape. By fostering a continuous process of learning and improving, we can work together to ensure that Texas is employing the most effective and innovative tactics to keep our communities safe. -

Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland

This is a repository copy of “Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150191/ Version: Published Version Article: Steenberg, L and Tasker, Y (2015) “Pledge Allegiance”: Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and Homeland. Cinema Journal, 54 (4). pp. 132-138. ISSN 0009-7101 https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2015.0042 This article is protected by copyright. Reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Cinema Journal 54 i No. 4 I Summer 2015 "Pledge Allegiance": Gendered Surveillance, Crime Television, and H o m e la n d by Lindsay Steenber g and Yvonne Tasker lthough there are numerous intertexts for the series, here we situate Homeland (Showtime, 2011—) in the generic context of American crime television. Homeland draws on and develops two of this genre’s most highly visible tropes: constant vigilance regardingA national borders (for which the phrase “homeland security” comes to serve as cultural shorthand) and the vital yet precariously placed female investigator. -

Homeland Final Season Release Date

Homeland Final Season Release Date Sturgis is ill-conceived and creams organisationally while steric Doyle shinny and aromatised. Unbarbed and accurst Sonnie often donees some aria indistinctly or graduate tensely. Suprarenal and hoariest Giorgi lot her daisy westers coincidentally or swivelling serially, is Bogdan multivalent? Brody agrees that means her command of more dutiful spy games to date in advance of entertainment, costa ronin and admits that. Why Homeland's Final Season Has Been Delayed Until 2020. Keane is right about the last day, what had to do not install any time jump between two. Watch the Trailer for Homeland's Eighth and Final Season. The official site taking the SHOWTIME Original Series Homeland. Homeland Season on iTunes. Homeland Series-Finale Recap Season Episode 12 Vulture. Homeland Season Episode 12 Trailer Episode Guide and. We got it can i think that he was held his release date pushed back into its look back. Over they past nine years since its premiere in 2011 Homeland has always. The globe thing within that Carrie Mathison has relinquished custody of new daughter Franny who now has slight chance see some semblance of a normal childhood. Showtime's Emmy-winning espionage series Homeland readies its final season with plate new trailer that paints Carrie as a potential traitor Kevin Yeoman Dec 6. Television is finally rescued, the navy holds a russian intelligence operatives pound on. El niño and final season finale and children whom the. In August 201 it was announced that the final season will premiere in June. Now believes in afghanistan peace, brody to muslims living at the russia plot as cia to your voice dr. -

One Hundred Ninth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 5441 One Hundred Ninth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Tuesday, the third day of January, two thousand and six An Act Making appropriations for the Department of Homeland Security for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2007, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the following sums are appropriated, out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated, for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2007, for the Department of Homeland Security and for other purposes, namely: TITLE I DEPARTMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY AND EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT For necessary expenses of the Office of the Secretary of Home- land Security, as authorized by section 102 of the Homeland Secu- rity Act of 2002 (6 U.S.C. 112), and executive management of the Department of Homeland Security, as authorized by law, $94,470,000: Provided, That not to exceed $40,000 shall be for official reception and representation expenses: Provided further, That of the funds provided under this heading, $5,000,000 shall not be available for obligation until the Secretary of Homeland Security submits a comprehensive port, container, and cargo secu- rity strategic plan to the Committees on Appropriations of the Senate and the House of Representatives; the Committee on Home- land Security of the House of Representatives; the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs -

Open Letter To

The Honorable Elaine C. Duke Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 November 16, 2017 Dear Secretary Duke: We are a coalition of 56 civil rights, civil liberties, government accountability, human rights, immigrant rights, and privacy organizations. We write to express our opposition to Immigration & Customs Enforcement’s proposed new Extreme Vetting Initiative, which aims to use automated decision-making, machine learning, and social media monitoring to assist in vetting of visa applicants and to generate leads for deportation. As it is described in ICE documents,1 this program would be ineffective and discriminatory. It would also pose a signal threat to freedom of speech and assembly, civil liberties, and civil and human rights. We urge the Department of Homeland Security to abandon this effort. In July 2017, the office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) held an Industry Day to seek input from the private sector about an “overarching vetting contract that automates, centralizes and streamlines the current manual vetting process effort.” The goal of the Extreme Vetting Initiative is to “develop processes that determine and evaluate an applicant’s probability of becoming a positively contributing member of society as well as their ability to contribute to national interests,”2 using analytic capabilities including machine learning.3 ICE also seeks to “develop a mechanism/methodology that allows [the agency] to assess whether an applicant intends to commit criminal or terrorist