Elan and Claerwen Valleys, Powys: Historical Briefing Paper1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gwastedyn Church Trail Leaflet

St. Clement’s Rhayader to Nantgwillt (5.2 miles, mostly tarmac, fairly flat) From the church gate turn right along Church Street past the garage, then turn right down Castle Road to the gate into the park. On your left is the site of Rhayader Castle built of wood in 1177 by Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth. It was finally destroyed in 1231. Go through the gates into the park and follow the path down to the play area. Turn left along the bank of the river. On the opposite bank a waterfall enters the river, 100 yards on you will see the ruins of one of many flannel mills on this stretch of the Wye. Follow the path across a car park, between buildings to the main road. Turn right over Rhayader bridge. Alternatively, from the church turn right down Church Street and then right down Bridge Street to the bridge passing the Old Police Station (built 1870) and Tabernacle Chapel (originally built 1688) on the left. Peering over the left parapet of the bridge you will see the remains of the waterfall that gave Rhayader its name. Continue through Cwmdauddwr past the old School (1794-1978) next to St Bride’s Church on the left. Continue out of the village until you reach the Elan Valley trail (signposted Builth and Aberystwyth) and follow the cycle path all the way to Elan Village. The path follows the route of the railways that delivered provisions during the construction of the Elan Valley dams. On the way you will pass over Rhayader Tunnel nature reserve, home to Brown long eared, Daubenton’s and Natterer’s bats. -

2 Powys Local Development Plan Written Statement

Powys LDP 2011-2026: Deposit Draft with Focussed Changes and Further Focussed Changes plus Matters Arising Changes September 2017 2 Powys Local Development Plan 2011 – 2026 1/4/2011 to 31/3/2026 Written Statement Adopted April 2018 (Proposals & Inset Maps published separately) Adopted Powys Local Development Plan 2011-2026 This page left intentionally blank Cyngor Sir Powys County Council Adopted Powys Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Foreword I am pleased to introduce the Powys County Council Local Development Plan as adopted by the Council on 17th April 2017. I am sincerely grateful to the efforts of everyone who has helped contribute to the making of this Plan which is so important for the future of Powys. Importantly, the Plan sets out a clear and strong strategy for meeting the future needs of the county’s communities over the next decade. By focussing development on our market towns and largest villages, it provides the direction and certainty to support investment and enable economic opportunities to be seized, to grow and support viable service centres and for housing development to accommodate our growing and changing household needs. At the same time the Plan provides the protection for our outstanding and important natural, built and cultural environments that make Powys such an attractive and special place in which to live, work, visit and enjoy. Our efforts along with all our partners must now shift to delivering the Plan for the benefit of our communities. Councillor Martin Weale Portfolio Holder for Economy and Planning -

Brecknock Rare Plant Register Species of Interest That Are Not Native Or Archaeophyte S8/1

Brecknock Rare Plant Register Species of interest that are not native or archaeophyte S8/1 S8/1 Acanthus mollis 270m Status Local Welsh Red Data GB Red Data S42 National Sites Bear's-breech Troed yr arth Neophyte LR 1 Jun 2013 Acanthus mollis SO2112 Blackrock Mons: Llanelly: SSSI0733, SAC08 DB⁴ S8/2 Acer platanoides 260m Status Local Welsh Red Data GB Red Data S42 National Sites Norway Maple Masarnen Norwy 70m Neophyte NLS 18 Nov 2020 Acer platanoides SO0207 Nant Ffrwd, Merthyr Tydfil MT: Vaynor IR¹⁰ Oct 2020 Acer platanoides SO0012 Llwyn Onn (Mid) MT: Vaynor IR⁵ Apr 2020Acer platanoides SN9152 Celsau CFA11: Treflys JC¹ Mar 2020 Acer platanoides SO2314 Llanelly Mons: Llanelly JC¹ Feb 2019Acer platanoides SN9758 Cwm Crogau CFA11: Llanafanfawr DB¹ Oct 2018 Acer platanoides SO0924 Castle Farm CFA12: Talybont-On-Usk DB¹ Jan 2018 Acer platanoides SN9208 Afon Mellte CFA15: Ystradfellte: SSSI0451, DB⁴ SAC71, IPA139 Apr 2017Acer platanoides SN9665 Wernnewydd CFA09: Llanwrthwl DB¹ Jul 2016 Acer platanoides SO0627 Usk CFA12: Llanfrynach DB¹ Jun 2015Acer platanoides SN8411 Coelbren CFA15: Tawe-Uchaf DB² Sep 2014Acer platanoides SO1937 Tregoyd Villa field CFA13: Gwernyfed DB¹ Jan 2014 Acer platanoides SO2316 Cwrt y Gollen site CFA14: Grwyney… DB¹ Apr 2012 Acer platanoides SO0528 Brecon CFA12: Brecon DB¹⁷ 2008 Acer platanoides SO1223 Llansantffraed CFA12: Talybont-On-Usk DB² May 2002Acer platanoides SO1940 Below Little Ffordd-fawr CFA13: Llanigon DB² Apr 2002Acer platanoides SO2142 Hay on Wye CFA13: Llanigon DB² Jul 2000 Acer platanoides SO2821 Pont -

Königreichs Zur Abgrenzung Der Der Kommission in Übereinstimmung

19 . 5 . 75 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 128/23 1 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . April 1975 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG (Vereinigtes Königreich ) (75/276/EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN 1973 nach Abzug der direkten Beihilfen, der hill GEMEINSCHAFTEN — production grants). gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro Als Merkmal für die in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buch päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, stabe c ) der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG genannte ge ringe Bevölkerungsdichte wird eine Bevölkerungs gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75/268/EWG des Rates ziffer von höchstens 36 Einwohnern je km2 zugrunde vom 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berg gelegt ( nationaler Mittelwert 228 , Mittelwert in der gebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebie Gemeinschaft 168 Einwohner je km2 ). Der Mindest ten (*), insbesondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2, anteil der landwirtschaftlichen Erwerbspersonen an der gesamten Erwerbsbevölkerung beträgt 19 % auf Vorschlag der Kommission, ( nationaler Mittelwert 3,08 % , Mittelwert in der Gemeinschaft 9,58 % ). nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments , Eigenart und Niveau der vorstehend genannten nach Stellungnahme des Wirtschafts- und Sozialaus Merkmale, die von der Regierung des Vereinigten schusses (2 ), Königreichs zur Abgrenzung der der Kommission mitgeteilten Gebiete herangezogen wurden, ent sprechen den Merkmalen der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : der Richtlinie -

'IARRIAGES Introduction This Volume of 'Stray' Marriages Is Published with the Hope That It Will Prove

S T R A Y S Volume One: !'IARRIAGES Introduction This volume of 'stray' marriages is published with the hope that it will prove of some value as an additional source for the familv historian. For economic reasons, the 9rooms' names only are listed. Often people married many miles from their own parishes and sometimes also away from the parish of the spouse. Tracking down such a 'stray marriage' can involve fruitless and dishearteninq searches and may halt progress for many years. - Included here are 'strays', who were married in another parish within the county of Powys, or in another county. There are also a few non-Powys 'strays' from adjoining counties, particularly some which may be connected with Powys families. For those researchers puzzled and confused by the thought of dealing with patronymics, when looking for their Welsh ancestors, a few are to be found here and are ' indicated by an asterisk. A simple study of these few examples may help in a search for others, although it must be said, that this is not so easy when the father's name is not given. I would like to thank all those members who have helped in anyway with the compilation of this booklet. A second collection is already in progress; please· send any contributions to me. Doreen Carver Powys Strays Co-ordinator January 1984 WAL ES POWYS FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY 'STRAYS' M A R R I A G E S - 16.7.1757 JOHN ANGEL , bach.of Towyn,Merioneth = JANE EVANS, Former anrl r·r"~"nt 1.:ount les spin. -

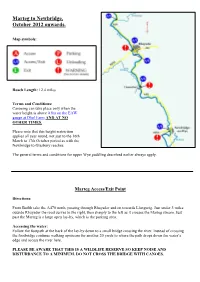

Marteg to Newbridge, October 2012 Onwards

Marteg to Newbridge, October 2012 onwards. Map symbols: Reach Length: 12.4 miles Terms and Conditions: Canoeing can take place only when the water height is above 0.8m on the EAW gauge at Dhol Farm AND AT NO OTHER TIMES. Please note that this height restriction applies all year round, not just to the 16th March to 17th October period as with the Newbridge to Glasbury reaches. The general terms and conditions for upper Wye paddling described earlier always apply. Marteg Access/Exit Point Directions: From Builth take the A470 north, passing through Rhayader and on towards Llangurig. Just under 3 miles outside Rhayader the road curves to the right, then sharply to the left as it crosses the Marteg stream. Just past the Marteg is a large open lay-by, which is the parking area. Accessing the water: Follow the footpath at the back of the lay-by down to a small bridge crossing the river. Instead of crossing the footbridge continue walking upstream for another 20 yards to where the path drops down the water’s edge and access the river here. PLEASE BE AWARE THAT THIS IS A WILDLIFE RESERVE SO KEEP NOISE AND DISTURBANCE TO A MINIMUM. DO NOT CROSS THE BRIDGE WITH CANOES. Rhayader Access/Exit Point (1) This exit point is for those who wish to avoid the grade IV rapids at Rhayader Bridge (highlighted by the exclamation mark on the map below), which can be a serious challenge to all but the most experienced paddler, especially in high water. Directions: From the centre of Rhayader (monument) take the B4518 (Bridge Street) in a westerly direction towards Elan Valley. -

Review of Community Boundaries in the County of Powys

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL’S PROPOSALS 3. THE COMMISSION’S CONSIDERATION 4. PROCEDURE 5. PROPOSALS 6. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 7. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT The Local Government Boundary Commission For Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 20395031 Fax Number: (029) 20395250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk Andrew Davies AM Minister for Social Justice and Public Service Delivery Welsh Assembly Government REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE COUNTY OF POWYS REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Powys County Council have conducted a review of the community boundaries and community electoral arrangements under Sections 55(2) and 57 (4) of the Local Government Act 1972 as amended by the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994 (the Act). In accordance with Section 55(2) of the Act Powys County Council submitted a report to the Commission detailing their proposals for changes to a number of community boundaries in their area (Appendix A). 1.2 We have considered Powys County Council’s report in accordance with Section 55(3) of the Act and submit the following report on the Council’s recommendations. 2. POWYS COUNTY COUNCIL’S PROPOSALS 2.1 Powys County Council’s proposals were submitted to the Commission on 7 November 2006 (Appendix A). The Commission have not received any representations about the proposals. -

Gwastedyn Profile

Parish Profile for The Parish of Gwastedyn in The Diocese of Swansea and Brecon Introduction We are delighted that you have requested a copy of this profile. We hope this will give you an insight into life within the parish of Gwastedyn and answer any questions you may have. The aim of all our churches is to serve God, the people of God and all who live and work in this beautiful part of Wales. We aim to bring God and His Son Jesus Christ closer into the everyday lives of people throughout our community, young and old alike through our regular worship, and community events. The Area Gwastedyn is a large rural Parish comprising 7 churches and a church site, centered around the Market Town of Rhayader in Powys, Mid-Wales. Rhayader, meaning “waterfall on the Wye” is a small market town situated in beautiful mid Wales, and is a perfect base for exploring the surrounding countryside. The Parish vicarage is located in the Town. Rhayader is a bustling historic market town. The first town on the river Wye, with an attractive stone bridge and impressive clock tower in the centre. It is a vital centre for the local farming community, and thriving tourism industry. The town lies in the heart of Wales, intersected by important routes to England to the East, and to North and South Wales. It has 2 car parks, and is within 12 miles of the railway station at Llandrindod Wells, with a regular bus service to the surrounding area, and farther afield. Internet access is constantly improving, and high speed broadband is available. -

SOUTH WALES. Fhayadert

DIRECTORY.] SOUTH WALES. FHAYADERt postmaster. Letters arrive from ~ part8 at 6.40 School At.te.ndanoe Oom.mittee. 1 a.m. & 5.20 p.m.; delivery commences at 1.15 8.m. Meets at Justices' rQOIWl on,. e'V~~ a~tet-nate w~. ~fJ:! p.m &; 5.30 'p.m, town OILY; &; dispatched at 6.50 p.m. to Clerk, George l\:lorgan Jarman, North street, Rhayadet all parts i box closing at 6.30 p.tu. & with extra !d. Attendance Officers" Richard Price, North at. 'Rhayad~ stamp at 6.35 p.m. Box cleared on sundays -at 6.30 &; John Griffiths. inn. Llandrindod p.m.; delivery commences at 9.40 ".m County Magistrates for the Petty Sessional Divudon of Rural Ilistrid Council. .. Rhayader. Meets at Justices' rOOmil on every alternate wedJ a' EvaUS' Edward Middleton esq. B.A. Llynbarried, Rhaya- 12 nOOn. der, chairman Clerk, Georg& Morgan Jarman, North stre~ Rhayader Carter John Corrie esq. Cefnfaes, Nantmel Treasurer, Geo. R8&, North &i South Wales Bank,Rhayadr Lewis-Uoyd Robert esq. D.L. Bryntirion, Nantmel Medical Officers of Health, Alfred GordOIi Richardson Lloyd-Verney Col. George Hope, Clochfaen, Llanidloes M.B., C.M. G~anant, Rhayader &; William Bowen Da.viel Morgan Richard esq. Llwyndre, Rhayader L.R.C.P.Lond. Llandrindod Wells Powell David Price esq. Howey hall, Llandrindod Sanitary Inspectors, Jamall Richard' Powell, Llanyre, Prickard Rev. Wm. Edward M.A. Dderw, Cwmdauddwr Llandrindod Wells R.S.O.; &; Robt. W.orthing,Rha.yadr Sladen Major-General, John Ramsey R.A., D.L. Rhydol- dog, Rhayader Publio Establishment~ Williams Edward esq. -

The Relationship Between Iron Age Hill Forts, Roman Settlements and Metallurgy on the Atlantic Fringe

The Relationship between Iron Age Hill Forts, Roman Settlements and Metallurgy on the Atlantic Fringe Keith Haylock BSc Department of Geography and Earth Sciences Supervisors Professor John Grattan, Professor Henry Lamb and Dr Toby Driver Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Aberystwyth University 2015 0 Abstract This thesis presents geochemical records of metalliferous enrichment of soils and isotope analysis of metal finds at Iron Age and Romano-British period settlements in North Ceredigion, Mid Wales, UK. The research sets out to explore whether North Ceredigion’s Iron Age sites had similar metal-production functions to other sites along the Atlantic fringe. Six sites were surveyed using portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF), a previously unused method in the archaeology of Mid Wales. Also tested was the pXRF (Niton XLt700 pXRF) with regard to how environmentally driven matrix effects may alter its in situ analyses results. Portable x-ray fluorescence was further used to analyse testing a range of certified reference materials (CRM) and site samples to assess target elements (Pb, Cu, Zn and Fe) for comparative accuracy and precision against Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) for both in situ and laboratory sampling. At Castell Grogwynion, one of the Iron Age sites surveyed recorded > 20 times Pb enrichment compared to back ground values of 110 ppm. Further geophysical surveys confirmed that high dipolar signals correlated to the pXRF Pb hotspots were similar to other known Iron Age and Roman period smelting sites, but the subsequent excavation only unearthed broken pottery and other waste midden development. -

The National and Community Averages Being 228 And

19 . 5 . 75 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 128/231 COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 28 April 1975 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive No 75/268/EEC (United Kingdom ) (75/276/EEC ) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, 75% of the national average (£ 1 072 and £ 1 436 respectively); Having regard to the Treaty establishing the Euro pean Economic Community ; Whereas the index relating to the low population density referred to in Article 3 ( 4) ( c ) of Directive Having regard to Council Directive No 75/268/ No 75/268/EEC does not exceed 36 inhabitants per EEC (*) of 28 April 1975 on mountain and hill square kilometre ( the national and Community farming and farming in certain less-favoured areas , averages being 228 and 168 inhabitants per square and in particular Article 2 ( 2 ) thereof ; kilometre respectively ; whereas the minimum propor tion of the working population engaged in agriculture as a percentage of the total working population is Having regard to the proposal from the Commission ; 19% ( the national and Community averages being 3-08 and 9-58 % respectively); Having regard to the Opinion of the European Parliament ; "Whereas the nature and level of the abovementioned indices, utilized by the Government of the United Having regard to the Opinion of the Economic and Kingdom to define the areas notified to the Commis Social Committee ( 2 ); sion , corresponds to the characteristics of less favoured farming areas referred to in Article 3 (4) of Whereas the United -

William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 6-2005 William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe Andrea Yount Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Yount, Andrea, "William Morris and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings: Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Historic Preservation in Europe" (2005). Dissertations. 1079. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/1079 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM MORRIS AND THE SOCIETY FOR THE PROTECTION OF ANCIENT BUILDINGS: NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY IDSTORIC PRESERVATION IN EUROPE by Andrea Yount A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History Dale P6rter, Adviser Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan June 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. ® UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3183594 Copyright 2005 by Yount, Andrea Elizabeth All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.