JOINT DISTRIBUTIONS of NUMBERS of SUCCESS-RUNS and FAILURES UNTIL the FIRST CONSECUTIVE K SUCCESSES*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beta-Binomial Distribution Introduction Bayesian Derivation

In Danish: 2005-09-19 / SLB Translated: 2008-05-28 / SLB Bayesian Statistics, Simulation and Software The beta-binomial distribution I have translated this document, written for another course in Danish, almost as is. I have kept the references to Lee, the textbook used for that course. Introduction In Lee: Bayesian Statistics, the beta-binomial distribution is very shortly mentioned as the predictive distribution for the binomial distribution, given the conjugate prior distribution, the beta distribution. (In Lee, see pp. 78, 214, 156.) Here we shall treat it slightly more in depth, partly because it emerges in the WinBUGS example in Lee x 9.7, and partly because it possibly can be useful for your project work. Bayesian Derivation We make n independent Bernoulli trials (0-1 trials) with probability parameter π. It is well known that the number of successes x has the binomial distribution. Considering the probability parameter π unknown (but of course the sample-size parameter n is known), we have xjπ ∼ bin(n; π); where in generic1 notation n p(xjπ) = πx(1 − π)1−x; x = 0; 1; : : : ; n: x We assume as prior distribution for π a beta distribution, i.e. π ∼ beta(α; β); 1By this we mean that p is not a fixed function, but denotes the density function (in the discrete case also called the probability function) for the random variable the value of which is argument for p. 1 with density function 1 p(π) = πα−1(1 − π)β−1; 0 < π < 1: B(α; β) I remind you that the beta function can be expressed by the gamma function: Γ(α)Γ(β) B(α; β) = : (1) Γ(α + β) In Lee, x 3.1 is shown that the posterior distribution is a beta distribution as well, πjx ∼ beta(α + x; β + n − x): (Because of this result we say that the beta distribution is conjugate distribution to the binomial distribution.) We shall now derive the predictive distribution, that is finding p(x). -

9. Binomial Distribution

J. K. SHAH CLASSES Binomial Distribution 9. Binomial Distribution THEORETICAL DISTRIBUTION (Exists only in theory) 1. Theoretical Distribution is a distribution where the variables are distributed according to some definite mathematical laws. 2. In other words, Theoretical Distributions are mathematical models; where the frequencies / probabilities are calculated by mathematical computation. 3. Theoretical Distribution are also called as Expected Variance Distribution or Frequency Distribution 4. THEORETICAL DISTRIBUTION DISCRETE CONTINUOUS BINOMIAL POISSON Distribution Distribution NORMAL OR Student’s ‘t’ Chi-square Snedecor’s GAUSSIAN Distribution Distribution F-Distribution Distribution A. Binomial Distribution (Bernoulli Distribution) 1. This distribution is a discrete probability Distribution where the variable ‘x’ can assume only discrete values i.e. x = 0, 1, 2, 3,....... n 2. This distribution is derived from a special type of random experiment known as Bernoulli Experiment or Bernoulli Trials , which has the following characteristics (i) Each trial must be associated with two mutually exclusive & exhaustive outcomes – SUCCESS and FAILURE . Usually the probability of success is denoted by ‘p’ and that of the failure by ‘q’ where q = 1-p and therefore p + q = 1. (ii) The trials must be independent under identical conditions. (iii) The number of trial must be finite (countably finite). (iv) Probability of success and failure remains unchanged throughout the process. : 442 : J. K. SHAH CLASSES Binomial Distribution Note 1 : A ‘trial’ is an attempt to produce outcomes which is neither sure nor impossible in nature. Note 2 : The conditions mentioned may also be treated as the conditions for Binomial Distributions. 3. Characteristics or Properties of Binomial Distribution (i) It is a bi parametric distribution i.e. -

Chapter 6 Continuous Random Variables and Probability

EF 507 QUANTITATIVE METHODS FOR ECONOMICS AND FINANCE FALL 2019 Chapter 6 Continuous Random Variables and Probability Distributions Chap 6-1 Probability Distributions Probability Distributions Ch. 5 Discrete Continuous Ch. 6 Probability Probability Distributions Distributions Binomial Uniform Hypergeometric Normal Poisson Exponential Chap 6-2/62 Continuous Probability Distributions § A continuous random variable is a variable that can assume any value in an interval § thickness of an item § time required to complete a task § temperature of a solution § height in inches § These can potentially take on any value, depending only on the ability to measure accurately. Chap 6-3/62 Cumulative Distribution Function § The cumulative distribution function, F(x), for a continuous random variable X expresses the probability that X does not exceed the value of x F(x) = P(X £ x) § Let a and b be two possible values of X, with a < b. The probability that X lies between a and b is P(a < X < b) = F(b) -F(a) Chap 6-4/62 Probability Density Function The probability density function, f(x), of random variable X has the following properties: 1. f(x) > 0 for all values of x 2. The area under the probability density function f(x) over all values of the random variable X is equal to 1.0 3. The probability that X lies between two values is the area under the density function graph between the two values 4. The cumulative density function F(x0) is the area under the probability density function f(x) from the minimum x value up to x0 x0 f(x ) = f(x)dx 0 ò xm where -

3.2.3 Binomial Distribution

3.2.3 Binomial Distribution The binomial distribution is based on the idea of a Bernoulli trial. A Bernoulli trail is an experiment with two, and only two, possible outcomes. A random variable X has a Bernoulli(p) distribution if 8 > <1 with probability p X = > :0 with probability 1 − p, where 0 ≤ p ≤ 1. The value X = 1 is often termed a “success” and X = 0 is termed a “failure”. The mean and variance of a Bernoulli(p) random variable are easily seen to be EX = (1)(p) + (0)(1 − p) = p and VarX = (1 − p)2p + (0 − p)2(1 − p) = p(1 − p). In a sequence of n identical, independent Bernoulli trials, each with success probability p, define the random variables X1,...,Xn by 8 > <1 with probability p X = i > :0 with probability 1 − p. The random variable Xn Y = Xi i=1 has the binomial distribution and it the number of sucesses among n independent trials. The probability mass function of Y is µ ¶ ¡ ¢ n ¡ ¢ P Y = y = py 1 − p n−y. y For this distribution, t n EX = np, Var(X) = np(1 − p),MX (t) = [pe + (1 − p)] . 1 Theorem 3.2.2 (Binomial theorem) For any real numbers x and y and integer n ≥ 0, µ ¶ Xn n (x + y)n = xiyn−i. i i=0 If we take x = p and y = 1 − p, we get µ ¶ Xn n 1 = (p + (1 − p))n = pi(1 − p)n−i. i i=0 Example 3.2.2 (Dice probabilities) Suppose we are interested in finding the probability of obtaining at least one 6 in four rolls of a fair die. -

Solutions to the Exercises

Solutions to the Exercises Chapter 1 Solution 1.1 (a) Your computer may be programmed to allocate borderline cases to the next group down, or the next group up; and it may or may not manage to follow this rule consistently, depending on its handling of the numbers involved. Following a rule which says 'move borderline cases to the next group up', these are the five classifications. (i) 1.0-1.2 1.2-1.4 1.4-1.6 1.6-1.8 1.8-2.0 2.0-2.2 2.2-2.4 6 6 4 8 4 3 4 2.4-2.6 2.6-2.8 2.8-3.0 3.0-3.2 3.2-3.4 3.4-3.6 3.6-3.8 6 3 2 2 0 1 1 (ii) 1.0-1.3 1.3-1.6 1.6-1.9 1.9-2.2 2.2-2.5 10 6 10 5 6 2.5-2.8 2.8-3.1 3.1-3.4 3.4-3.7 7 3 1 2 (iii) 0.8-1.1 1.1-1.4 1.4-1.7 1.7-2.0 2.0-2.3 2 10 6 10 7 2.3-2.6 2.6-2.9 2.9-3.2 3.2-3.5 3.5-3.8 6 4 3 1 1 (iv) 0.85-1.15 1.15-1.45 1.45-1.75 1.75-2.05 2.05-2.35 4 9 8 9 5 2.35-2.65 2.65-2.95 2.95-3.25 3.25-3.55 3.55-3.85 7 3 3 1 1 (V) 0.9-1.2 1.2-1.5 1.5-1.8 1.8-2.1 2.1-2.4 6 7 11 7 4 2.4-2.7 2.7-3.0 3.0-3.3 3.3-3.6 3.6-3.9 7 4 2 1 1 (b) Computer graphics: the diagrams are shown in Figures 1.9 to 1.11. -

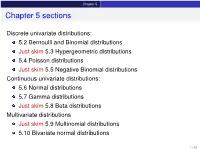

Chapter 5 Sections

Chapter 5 Chapter 5 sections Discrete univariate distributions: 5.2 Bernoulli and Binomial distributions Just skim 5.3 Hypergeometric distributions 5.4 Poisson distributions Just skim 5.5 Negative Binomial distributions Continuous univariate distributions: 5.6 Normal distributions 5.7 Gamma distributions Just skim 5.8 Beta distributions Multivariate distributions Just skim 5.9 Multinomial distributions 5.10 Bivariate normal distributions 1 / 43 Chapter 5 5.1 Introduction Families of distributions How: Parameter and Parameter space pf /pdf and cdf - new notation: f (xj parameters ) Mean, variance and the m.g.f. (t) Features, connections to other distributions, approximation Reasoning behind a distribution Why: Natural justification for certain experiments A model for the uncertainty in an experiment All models are wrong, but some are useful – George Box 2 / 43 Chapter 5 5.2 Bernoulli and Binomial distributions Bernoulli distributions Def: Bernoulli distributions – Bernoulli(p) A r.v. X has the Bernoulli distribution with parameter p if P(X = 1) = p and P(X = 0) = 1 − p. The pf of X is px (1 − p)1−x for x = 0; 1 f (xjp) = 0 otherwise Parameter space: p 2 [0; 1] In an experiment with only two possible outcomes, “success” and “failure”, let X = number successes. Then X ∼ Bernoulli(p) where p is the probability of success. E(X) = p, Var(X) = p(1 − p) and (t) = E(etX ) = pet + (1 − p) 8 < 0 for x < 0 The cdf is F(xjp) = 1 − p for 0 ≤ x < 1 : 1 for x ≥ 1 3 / 43 Chapter 5 5.2 Bernoulli and Binomial distributions Binomial distributions Def: Binomial distributions – Binomial(n; p) A r.v. -

A Note on Skew-Normal Distribution Approximation to the Negative Binomal Distribution

WSEAS TRANSACTIONS on MATHEMATICS Jyh-Jiuan Lin, Ching-Hui Chang, Rosemary Jou A NOTE ON SKEW-NORMAL DISTRIBUTION APPROXIMATION TO THE NEGATIVE BINOMAL DISTRIBUTION 1 2* 3 JYH-JIUAN LIN , CHING-HUI CHANG AND ROSEMARY JOU 1Department of Statistics Tamkang University 151 Ying-Chuan Road, Tamsui, Taipei County 251, Taiwan [email protected] 2Department of Applied Statistics and Information Science Ming Chuan University 5 De-Ming Road, Gui-Shan District, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan [email protected] 3 Graduate Institute of Management Sciences, Tamkang University 151 Ying-Chuan Road, Tamsui, Taipei County 251, Taiwan [email protected] Abstract: This article revisits the problem of approximating the negative binomial distribution. Its goal is to show that the skew-normal distribution, another alternative methodology, provides a much better approximation to negative binomial probabilities than the usual normal approximation. Key-Words: Central Limit Theorem, cumulative distribution function (cdf), skew-normal distribution, skew parameter. * Corresponding author ISSN: 1109-2769 32 Issue 1, Volume 9, January 2010 WSEAS TRANSACTIONS on MATHEMATICS Jyh-Jiuan Lin, Ching-Hui Chang, Rosemary Jou 1. INTRODUCTION where φ and Φ denote the standard normal pdf and cdf respectively. The This article revisits the problem of the parameter space is: μ ∈( −∞ , ∞), σ > 0 and negative binomial distribution approximation. Though the most commonly used solution of λ ∈(−∞ , ∞). Besides, the distribution approximating the negative binomial SN(0, 1, λ) with pdf distribution is by normal distribution, Peizer f( x | 0, 1, λ) = 2φ (x )Φ (λ x ) is called the and Pratt (1968) has investigated this problem standard skew-normal distribution. -

3 Multiple Discrete Random Variables

3 Multiple Discrete Random Variables 3.1 Joint densities Suppose we have a probability space (Ω, F, P) and now we have two discrete random variables X and Y on it. They have probability mass functions fX (x) and fY (y). However, knowing these two functions is not enough. We illustrate this with an example. Example: We flip a fair coin twice and define several RV’s: Let X1 be the number of heads on the first flip. (So X1 = 0, 1.) Let X2 be the number of heads on the second flip. Let Y = 1 − X1. All three RV’s have the same p.m.f. : f(0) = 1/2, f(1) = 1/2. So if we only look at p.m.f.’s of individual RV’s, the pair X1,X2 looks just like the pair X1,Y . But these pairs are very different. For example, with the pair X1,Y , if we know the value of X1 then the value of Y is determined. But for the pair X1,X2, knowning the value of X1 tells us nothing about X2. Later we will define “independence” for RV’s and see that X1,X2 are an example of a pair of independent RV’s. We need to encode information from P about what our random variables do together, so we introduce the following object. Definition 1. If X and Y are discrete RV’s, their joint probability mass function is f(x, y)= P(X = x, Y = y) As always, the comma in the event X = x, Y = y means “and”. -

Discrete Distributions: Empirical, Bernoulli, Binomial, Poisson

Empirical Distributions An empirical distribution is one for which each possible event is assigned a probability derived from experimental observation. It is assumed that the events are independent and the sum of the probabilities is 1. An empirical distribution may represent either a continuous or a discrete distribution. If it represents a discrete distribution, then sampling is done “on step”. If it represents a continuous distribution, then sampling is done via “interpolation”. The way the table is described usually determines if an empirical distribution is to be handled discretely or continuously; e.g., discrete description continuous description value probability value probability 10 .1 0 – 10- .1 20 .15 10 – 20- .15 35 .4 20 – 35- .4 40 .3 35 – 40- .3 60 .05 40 – 60- .05 To use linear interpolation for continuous sampling, the discrete points on the end of each step need to be connected by line segments. This is represented in the graph below by the green line segments. The steps are represented in blue: rsample 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 x 0 .5 1 In the discrete case, sampling on step is accomplished by accumulating probabilities from the original table; e.g., for x = 0.4, accumulate probabilities until the cumulative probability exceeds 0.4; rsample is the event value at the point this happens (i.e., the cumulative probability 0.1+0.15+0.4 is the first to exceed 0.4, so the rsample value is 35). In the continuous case, the end points of the probability accumulation are needed, in this case x=0.25 and x=0.65 which represent the points (.25,20) and (.65,35) on the graph. -

Hand-Book on STATISTICAL DISTRIBUTIONS for Experimentalists

Internal Report SUF–PFY/96–01 Stockholm, 11 December 1996 1st revision, 31 October 1998 last modification 10 September 2007 Hand-book on STATISTICAL DISTRIBUTIONS for experimentalists by Christian Walck Particle Physics Group Fysikum University of Stockholm (e-mail: [email protected]) Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Random Number Generation .............................. 1 2 Probability Density Functions 3 2.1 Introduction ........................................ 3 2.2 Moments ......................................... 3 2.2.1 Errors of Moments ................................ 4 2.3 Characteristic Function ................................. 4 2.4 Probability Generating Function ............................ 5 2.5 Cumulants ......................................... 6 2.6 Random Number Generation .............................. 7 2.6.1 Cumulative Technique .............................. 7 2.6.2 Accept-Reject technique ............................. 7 2.6.3 Composition Techniques ............................. 8 2.7 Multivariate Distributions ................................ 9 2.7.1 Multivariate Moments .............................. 9 2.7.2 Errors of Bivariate Moments .......................... 9 2.7.3 Joint Characteristic Function .......................... 10 2.7.4 Random Number Generation .......................... 11 3 Bernoulli Distribution 12 3.1 Introduction ........................................ 12 3.2 Relation to Other Distributions ............................. 12 4 Beta distribution 13 4.1 Introduction ....................................... -

Statistical Distributions

CHAPTER 10 Statistical Distributions In this chapter, we shall present some probability distributions that play a central role in econometric theory. First, we shall present the distributions of some discrete random variables that have either a finite set of values or that take values that can be indexed by the entire set of positive integers. We shall also present the multivariate generalisations of one of these distributions. Next, we shall present the distributions of some continuous random variables that take values in intervals of the real line or over the entirety of the real line. Amongst these is the normal distribution, which is of prime importance and for which we shall consider, in detail, the multivariate extensions. Associated with the multivariate normal distribution are the so-called sam- pling distributions that are important in the theory of statistical inference. We shall consider these distributions in the final section of the chapter, where it will transpire that they are special cases of the univariate distributions described in the preceding section. Discrete Distributions Suppose that there is a population of N elements, Np of which belong to class and N(1 p) to class c. When we select n elements at random from the populationA in n −successive trials,A we wish to know the probability of the event that x of them will be in and that n x of them will be in c. The probability will Abe affected b−y the way in which theA n elements are selected; and there are two ways of doing this. Either they can be put aside after they have been sampled, or else they can be restored to the population. -

Some Continuous and Discrete Distributions Table of Contents I

Some continuous and discrete distributions Table of contents I. Continuous distributions and transformation rules. A. Standard uniform distribution U[0; 1]. B. Uniform distribution U[a; b]. C. Standard normal distribution N(0; 1). D. Normal distribution N(¹; ). E. Standard exponential distribution. F. Exponential distribution with mean ¸. G. Standard Gamma distribution ¡(r; 1). H. Gamma distribution ¡(r; ¸). II. Discrete distributions and transformation rules. A. Bernoulli random variables. B. Binomial distribution. C. Poisson distribution. D. Geometric distribution. E. Negative binomial distribution. F. Hypergeometric distribution. 1 Continuous distributions. Each continuous distribution has a \standard" version and a more general rescaled version. The transformation from one to the other is always of the form Y = aX + b, with a > 0, and the resulting identities: y b fX ¡ f (y) = a (1) Y ³a ´ y b FY (y) = FX ¡ (2) Ã a ! E(Y ) = aE(X) + b (3) V ar(Y ) = a2V ar(X) (4) bt MY (t) = e MX (at) (5) 1 1.1 Standard uniform U[0; 1] This distribution is \pick a random number between 0 and 1". 1 if 0 < x < 1 fX (x) = ½ 0 otherwise 0 if x 0 · FX (x) = x if 0 x 1 8 · · < 1 if x 1 ¸ E(X) = 1:=2 V ar(X) = 1=12 et 1 M (t) = ¡ X t 1.2 Uniform U[a; b] This distribution is \pick a random number between a and b". To get a random number between a and b, take a random number between 0 and 1, multiply it by b a, and add a. The properties of this random variable are obtained by applying¡ rules (1{5) to the previous subsection.