Resonant-Beam Based Optical Wireless Power Charging and Data Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laser Safety: Hazards, Bioeffects, and Control Measures Laser Institute of America Gus Anibarro Education Manager

Laser Safety: Hazards, Bioeffects, and Control Measures Laser Institute of America Gus Anibarro Education Manager Laser Safety © Laser Institute of America 1 Laser Safety Overview Laser Safety Accidents Hazards Controls Laser Safety © Laser Institute of America 2 Laser Safety Training © Laser Institute of America Page 1 Laser Accidents & Incidents: Overview from one 1999 Survey Top 5 lasers: Nd:YAG, Ar, CO2, dye, diode Breakdown of incidents 16.9% 71% - eye injury Eye Skin 11.9% 11.9% - skin injury Non-beam 16.9% - non-beam incident 71% Data from Rockwell, RJ, ILSC 99 Proceedings, LIA Laser Safety © Laser Institute of America 3 Laser Accidents: Personnel Exposure Summary Accident Data Summary: Division of 395 events: 1964-1998 Technicians Exposed (81): 20.5% Scientists Exposed (78): 19.8% Students Exposed (46): 11.6% Patients Exposed (40): 10.1% Plant Workers Exposed (35): 8.9% Dr.s & Nurses Exposed (26): 6.6% Pilots & Military Exposed (26): 6.6% Spectators Exposed (25): 6.3% Laser Show Operators Exposed (11): 2.8% Equipment only damaged (10): 2.5% Field Service Exposed (10): 2.5% Office Staff (uninvolved) (7): 1.8% Data from Rockwell, RJ, ILSC 99 Proceedings, LIA Laser Safety © Laser Institute of America 4 Laser Safety Training © Laser Institute of America Page 2 Laser Accidents Eye Injury >70% of all incidents Retinal hemorrhage from Q- switched laser pulse. Visual Effect: Blind spot in field of vision. Laser Safety © Laser Institute of America 5 Laser Accidents: Research & Development Laboratory Most eye injuries have occurred -

Laser Pointer Safety About Laser Pointers Laser Pointers Are Completely Safe When Properly Used As a Visual Or Instructional Aid

Harvard University Radiation Safety Services Laser Pointer Safety About Laser Pointers Laser pointers are completely safe when properly used as a visual or instructional aid. However, they can cause serious eye damage when used improperly. There have been enough documented injuries from laser pointers to trigger a warning from the Food and Drug Administration (Alerts and Safety Notifications). Before deciding to use a laser pointer, presenters are reminded to consider alternate methods of calling attention to specific items. Most presentation software packages offer screen pointer options with the same features, but without the laser hazard. Selecting a Safe Laser Pointer 1) Choose low power lasers (Class 2) Whenever possible, select a Class 2 laser pointer because of the lower risk of eye damage. 2) Choose red-orange lasers (633 to 650 nm wavelength, choose closer to 635 nm) The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) researchers found that some green laser pointers can emit harmful levels of infrared radiation. The green laser pointers create green light beam in a three step process. A standard laser diode first generates near infrared light with a wavelength of 808nm, and pumps it into a ND:YVO4 crystal that converts the 808 nm light into infrared with a wavelength of 1064 nm. The 1064 nm light passes into a frequency doubling crystal that emits green light at a wavelength of 532nm finally. In most units, a combination of coatings and filters keeps all the infrared energy confined. But the researchers found that really inexpensive green lasers can lack an infrared filter altogether. One tested unit was so flawed that it released nine times more infrared energy than green light. -

Non-Ionizing Radiation Program Chattanooga NRP01 – Non-Ionizing Radiation Program Nashville

Memphis Knoxville Non-Ionizing Radiation Program Chattanooga NRP01 – Non-Ionizing Radiation Program Nashville Resp. Office: Research No./Title: NRP01 – Non-Ionizing Radiation Program Effective Date: 9/10/2020 Safety Affairs Category: Radiation Safety Last Review: New Next Review: 9/10/2023 Contact: Jabari Robinson, Radiation Safety Officer, 901.448.5223 jrobin91uthsc.edu Office of Research Safety Affairs Related Policies: SA0500-Laser Safety, & RSPL01-Laser Reg- istration and Inspection Policy PURPOSE Non-ionizing radiation (NIR) refers to electromagnetic radiation that does not have sufficient energy to ionize (remove electrons from) atoms or molecules. In general, NIR tends to be less hazardous to humans than ionizing radiation (ionizing radiation has a wavelength less than 100 nm or a photon energy > 12.4 eV). However, depending on the wavelength/frequency and the irradiance (or power density) value, NIR sources may present a human health hazard. Therefore, those working with non-ionizing radiation must take precautions to ensure they are not exposed to excessive levels of NIR. The Non-Ionizing Radiation (NIR) Safety Program is designed to help protect employees, students, and the general public from the harmful effects of non-ionizing radiation on campus. The NIR program is intended to provide a workplace where known hazards of NIR are mitigated. SCOPE The scope of this program applies to the Memphis campus of UTHSC and applies to non-ionizing radiation use and users on campus. TYPES OF NR There are three broad categories of NIR. They are optical radiation, microwave radiation, and radiofrequency radiation. Optical radiation includes ultraviolet, visible light, and infrared light. Please note that optical radiation resulting from laser use is addressed in the laser safety program. -

Laser Macular Burns in Children

Eye (2014) 28, 231–234 FastFast TrackTrack PaperPaper & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-222X/14 www.nature.com/eye 1,2 1,2 1,2 ‘Toy’ laser macular N Raoof , TKJ Chan , NK Rogers , CASE SERIES W Abdullah2, I Haq1, SP Kelly3 and FM Quhill1 burns in children Abstract consumers about the risk of eye and skin injuries from exposure to high-powered Purpose Laser ‘toys’ can be purchased laser pointers. FDA regulations limit the online and imported with relative ease; the energy output of hand-held laser pointers variety of such devices is a potential public to 5 milliwatts (mW).1 However, laser ‘toys’, safety concern. We describe five children of uncertain safety classification and which with maculopathy following exposure resemble low-power laser pointers, can be to laser ‘toys’. purchased online from outside Europe and Methods Case series of maculopathy USA. Such lasers have the potential for retinal following exposure to laser ‘toys’. damage. Importantly as laser technology Results Five children were seen in our continues to develop, more powerful Ophthalmic Unit with macular injuries portable (hand-held) lasers are being produced following exposure to laser ‘toys’. Clinically, at lower cost. We report five local children with three children had an acute vitelliform-like maculopathy following exposure to laser toys maculopathy which resolved to leave sub- purchased online and imported to the UK. foveal retinal pigment epithelium changes with reduced vision. One case was compli- cated by a choroidal neovascular membrane. Case reports Conclusion Laser ‘toys’, which resemble laser pointers, are increasingly available Case 1 1Department of over the internet. -

Laser Pointer Safety

Laser Pointer Safety INTRODUCTION The use of laser diode pointers that operate in the visible radiation region (400 to 760 nanometers [nm]) is becoming widespread. These pointers are intended for use by educators while presenting talks in the classroom or at conventions and meetings. A high-tech alternative to the retractable, metal pointer, the laser pointer beam will produce a small dot of light on whatever object at which it is aimed. It can draw an audience¹s attention to a particular key point in a slide show. Laser pointers are not regulated at Oklahoma State University although the university has a Laser Safety Committee. Only Class IIIb and Class IV lasers are covered under OSU’s Laser Safety Program. The power emitted by these laser pointers ranges from 1 to 5 milliwatts (mW). Laser Pointers are similar to devices used for other purposes such as the aligning of other lasers, laying pipes in construction, and as aiming devices for firearms. They are widely available at electronic stores, novelty shops, through mail order catalogs and by numerous other sources. At $20 or even less, laser pointers are in the price range of other electronic toys and have been treated as such by many parents and children. Laser Pointers are not toys! Although most of these devices contain warning labels, as required by FDA regulations, many have been erroneously advertised as "safe". The potential for hazard with laser pointers is generally considered to be limited to the unprotected eyes of individuals who might be exposed by a direct beam (intrabeam viewing). -

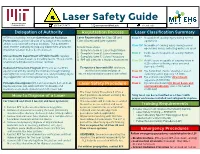

Laser Safety Guide

Laser Safety Guide 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 (617)-452-3477 [email protected] ehs.mit.edu Delegation of Authority Registration Process Laser Classification Summary MIT has a standing institute Committee on Radiation Laser Registration for Class 3B and Class 1* Incapable of causing injury during normal Protection to oversee all uses of radiation at the Institute Class 4 lasers and laser systems operations and its associated off campus locations. The Committee Class 1M Incapable of causing injury during normal gives the RPP authority to stop any experiment or process Follow these steps: operations unless collecting optics are used involving radiation that is deemed unsafe. 1. Complete form A: Laser Registration 2. Complete form B: Laser Inventory Class 2 Visible lasers incapable of causing injury in Massachusetts Department of Public Health regulate 3. Complete form C: Safety Procedure 0.25s. the use of radiation sources including lasers. They perform 4. RPP will perform a Hazard Assessment Class 2M Visible lasers incapable of causing injury in unannounced inspections of laser facilities. 0.25s unless collecting optics are used (typically <1mW) Radiation Protection Program (RPP) acts as the RPC’s To register a laser with RPP, and more, operational arm by serving the institute through training, visit the laser safety webpage at Class 3R Eye hazard for chronic viewing or use of oversight/risk assessment of laser use, and providing day to ehs.mit.edu/radiological-program/laser-safety/ collecting optics (typically 1-5 mW) day support for all matters pertaining to lasers. Class 3B Eye and skin hazard for direct beam exposure (5-500 mW). -

Laser Eye Safety for Telecommunications Systems

www.senko.com Application Note Laser Eye Safety for Telecommunications Systems Introduction aided by focusing from the lens of an eye, can cause laser radiation to be concentrated into an extremely small spot on the retina. A transient increase of only 10 °C can destroy retinal photoreceptor cells. If the laser is eyeball and may cause heating of the retina, whereas exposure to laser radiation with wavelengths less than 400 nm and greater than 1400 nm are largely absorbed by the cornea and lens, leading to the development of cataracts or burn injuries. Retina Iris Macula Cornea Optic nerve Pupil Vitreous Lens 1 Laser Eye Safety for Telecommunications Systems www.senko.com Infrared lasers are particularly hazardous, since the body’s protective “blink reflex” response is triggered only by visible light. For example, some people exposed to high power Nd:YAG laser emitting invisible 1064 nm radiation, may not feel pain or notice immediate damage to their eyesight. A pop or click noise emanating from the eyeball may be the only indication that retinal damage has occurred i.e. the retina was heated to over 100 °C resulting in localized explosive boiling accompanied by the immediate creation of a permanent blind spot. Ocular Absorption Site vs. Wavelength Visible and Near-infared Mid-infared and Far-infared Near-ultraviolet (400 - 1400nm) radiation (1400 - 1mm) and (315 - 390nm) radiation Far-ultraviolet (180nm - 315nm) radiation Lasers can cause damage in biological tissues, both to the eye and to the skin, due to several mechanisms. Thermal damage, or burn, occurs when tissues are heated to the point where denaturation of proteins occurs. -

Laser Safety

Laser Safety The George Washington University Office of Laboratory Safety Ross Hall, Suite B05 202-994-8258 LASER LASER stands for: Light Amplification by the Stimulated Emission of Radiation Laser Light Laser light – is monochromatic, unlike ordinary light which is made of a spectrum of many wavelengths. Because the light is all of the same wavelength, the light waves are said to be synchronous. – is directional and focused so that it does not spread out from the point of origin. Asynchronous, multi-directional Synchronous, light. monochromatic, directional light waves Uses of Lasers • Lasers are used in industry, communications, military, research and medical applications. • At GW, lasers are used in both research and medical procedures. How a Laser Works A laser consists of an optical cavity, a pumping system, and a lasing medium. – The optical cavity contains the media to be excited with mirrors to redirect the produced photons back along the same general path. – The pumping system uses various methods to raise the media to the lasing state. – The laser medium can be a solid (state), gas, liquid dye, or semiconductor. Source: OSHA Technical Manual, Section III: Chapter 6, Laser Hazards. Laser Media 1. Solid state lasers 2. Gas lasers 3. Excimer lasers (a combination of the terms excited and dimers) use reactive gases mixed with inert gases. 4. Dye lasers (complex organic dyes) 5. Semiconductor lasers (also called diode lasers) There are different safety hazards associated with the various laser media. Types of Lasers Lasers can be described by: • which part of the electromagnetic spectrum is represented: – Infrared – Visible Spectrum – Ultraviolet • the length of time the beam is active: – Continuous Wave – Pulsed – Ultra-short Pulsed Electromagnetic Spectrum Laser wavelengths are usually in the Ultraviolet, Visible or Infrared Regions of the Electromagnetic Spectrum. -

LSU School of Dentistry Laser Safety : Clinical

LSU School of Dentistry Laser Safety : Clinical SAFETY PROCEDURES FOR LASER (NON-IONIZING) RADIATION 1. PURPOSE This procedure sets forth the Louisiana State University (LSU) System non-ionizing radiation safety policy and procedural requirements of the program. The use of the term non-ionizing radiation in this document is defined as meaning non-ionizing radiation produced as a result of normal equipment use and which is at such a level that is recognized as harmful to humans. NOTE: This procedure does not cover non-ionizing radiation generated during welding, cutting, or burning activities. 2 .POLICY The LSU System policy is to limit exposure to personnel from non-ionizing radiation to levels as low as reasonably achievable; however, under no circumstances is exposure to exceed appropriate Louisiana or Federal regulatory limits. To implement this policy, LSU System has set up a non-ionizing radiation safety program to ensure: a. The use of equipment which produces non-ionizing radiation within LSU System for official business is used in a manner that will minimize risks to health and safety of the faculty, staff, students, and the general public. b. The identification of non-ionizing radiation source hazards. c. The prompt investigation of all reported non-ionizing radiation over-exposures and the establishment of immediate corrective action to prevent their recurrence. d. The maintenance of an accurate inventory for accountability of the hazardous non-ionizing radiation sources within the LSU System. 3 SAFETY PROCEDURES FOR LASER RADIATION 3.1 INTRODUCTION The term Laser is an acronym derived from "Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation." The effects of laser radiation are essentially the same as light generated by more conventional ultraviolet, infrared, and visible light sources. -

FDA Background Materials Prepared for the October 25-26 2016 Technical Electronic Product Radiation Safety Standards Committee

FDA Background Materials Prepared for the October 25-26 2016 Technical Electronic Product Radiation Safety Standards Committee Table of Contents DAY ONE 1) TEPRSSC: Scope and History (Page 2) 2) RF Radiation Products (Page 14) a) Microwave Ovens (Page 14) b) Wireless Power Transfer (Page 18) 3) Laser Products (Page 21) a) Update to Amendments to Laser Rule (Page 21) b) Laser LiDAR, Remotely Controlled Mobile Laser Products, and Laser Pointers (Page 26) c) Laser lamps for general illumination and LIPs (Page 32) d) Infrared applications (Page 36) 4) Sunlamp Products and Other Non-Coherent Light Sources (Page 38) a) Sunlamp Products—Performance Standard Amendments Update (Page 38) b) Non-Coherent Light Sources—New Initiatives (Page 39) DAY TWO 1) Radiation Therapy (Page 42) 2) Computed Tomography (Page 47) 3) Radiography & Fluoroscopy (Page 53) 4) Diagnostic and Therapeutic Ultrasound (Page 56) 5) IEC Standards vs. Performance Standards for Medical Devices (Page 59) 1 DAY ONE 1) TEPRSSC: Scope and History Introduction The Technical Electronic Product Radiation Safety Standards Committee (TEPRSSC) was established by the Radiation Control for Health and Safety Act of 1968 (see section 534 of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (the “FD&C Act” or the “Act”), 21 U.S.C. § 360kk): “The Secretary shall establish a Technical Electronic Product Radiation Safety Standards Committee…which he shall consult before prescribing any standard under this section.” Here “Standard” refers to performance standards for electronic products to control the emission of electronic product radiation. [1] The TEPRSSC Charter states that the Committee provides advice and consultation to the Commissioner of Food and Drugs on the technical feasibility, reasonableness, and practicability of performance standards for electronic products to control the emission of radiation from such products, and may recommend electronic product radiation safety standards to the Commissioner for consideration. -

NIH Non-Ionizing Radiation Program

National Institutes of Health Non-Ionizing Radiation Program 2018 Authored by the Division of Occupational Health and Safety (DOHS) Non- Ionizing Radiation Program (NIRP) Manager. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………… 2 I. PURPOSE………………………………………………………………… 2 II. SCOPE……………………………………………………………………. 3 III. RESPONSIBILITIES …………………………………………………….. 3 IV. REPORTING REQUIREMENTS…………………………..…………….. 5 ACRONYMS DOHS Division of Occupational Health and Safety LSAC Laser Safety Advisory Committee LSO Laser Safety Officer MRI Magnetic Resonance Imaging NIH National Institutes of Health NIR Non-Ionizing Radiation NIRP Non-Ionizing Radiation Program NMR Nuclear Magnetic Resonance OMS Occupational Medical Service ORS Office of Research Services PI Principal Investigator TAB Technical Assistance Branch INTRODUCTION Non-ionizing radiation (NIR) permeates the world around us and exists in many forms on the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to near-ultraviolet radiation. Fortunately, in contrast to ionizing radiation, NIR lacks sufficient energy to remove electrons from atoms and molecules and is therefore generally perceived as less harmful. However, exposure to significant amounts of NIR can result in tissue damage due to heat. For this reason and in consideration of incomplete epidemiological data, care is taken to limit exposure to NIR in accordance with consensus guidelines. I. PURPOSE The NIH Non-Ionizing Radiation Program (NIRP) is intended to minimize occupational exposure to NIR by: a) Providing employee information regarding the recognition, evaluation and control of the hazards associated with sources of NIR; b) Reviewing plans for the installation of new sources of NIR; c) When requested, providing affected employees with information regarding source- appropriate safety principles and best practices; and d) Evaluating NIR levels when requested by employees or when sources are identified during safety surveys. -

Princeton University Laser Safety Training Guide

Laser Safety Training Guide Environmental Health and Safety http://www.princeton.edu/ehs September 2007 LASER SAFETY TRAINING GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: LASER FUNDAMENTALS 3 LASER Theory And Operation 4 Components Of A Laser 5 Types Of Lasers 6 SECTION 2: LASER HAZARDS 8 BEAM-RELATED HAZARDS 8 Types of Beam Exposure 9 Eye 9 Skin 12 NON-BEAM HAZARDS 12 Electrical Hazards 13 Laser Generated Air Contaminants -- The “Plume” 14 Collateral and Plasma Radiation 14 Fire Hazards 15 Compressed Gases 15 Laser Dyes 15 SECTION 3: LASER HAZARD CLASSIFICATION 17 SECTION 4: LASER CONTROL MEASURES 19 Maximum Permissible Exposure (MPE) 19 Accessible Exposrue Limit 19 Optical Density (OD) 19 Nominal Hazard Zone (NHZ) 20 Control Measures by Laser Classification 21 Protective Equipment 27 Protective Eyewear 27 Laser Eye Protection Selection Process 27 Other Protective Equipment 28 Special Controls for UltraViolet and Infrared Lasers 29 SECTION 5: LASER SAFETY AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY 30 SECTION 6: GLOSSARY 33 APPENDIX A: SELECTED ANSI STANDARD TABLES 36 APPENDIX B: LASER SAFETY TIPS 43 APPENDIX C: LASER SAFETY CHECKLIST 44 2 Section 1: LASER FUNDAMENTALS Introduction The word laser is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. Lasers are used as research aides in many departments at Princeton University. In this document, the word laser will be limited to electromagnetic radiation-emitting devices using light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation at wavelengths from 180 nanometers to 1 millimeter. The electromagnetic spectrum includes energy ranging from gamma rays to electricity. Figure 1 illustrates the total electromagnetic spectrum and wavelengths of the various regions.