SUFI SAINTS and STATE POWER the Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District

PAKISTAN - Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District Union council ranking exercise, coordinated by UNOCHA and UNDP, is a joint effort of Government and humanitarian partners Community Restoration Food Education in the notified districts of 2011 floods in Sindh. Its purpose is to: Identify high priority union councils with outstanding needs. SHAHEED SHAHEED SHAHEED BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR Facilitate stackholders to plan/support interventions and divert Shah Shah Shah Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Gujri Gujri resources where they are most needed. Gul Gul Gujri Khadro Khadwari Khadro Khadwari Gul Khadro Khadwari Muhammad Muhammad Muhammad Laghari Laghari Laghari Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Provide common prioritization framework to clusters, agencies Shah Shah Serhari Chakar Kanhar Barhoon Barhoon Barhoon Shah Mardan Abad Mardan Abad Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mardan Abad Mian Chutiaryoon Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Khan Khan Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Khan Sanghar 1 and donors. Faqir HingoroLaghari Laghari Laghari Faqir Hingoro Faqir Hingoro Kurkali Kurkali Kurkali Jatia Jatia Jatia Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Manik Manik Manik Tahim Khipro Tahim Khipro First round of this exercise is completed from February - March Khori Khori Tahim Khipro Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Khori Pero Jan Nawaz DarhoonTando Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo Nauabad Nauabad Nauabad 2012. -

PESA-DP-Hyderabad-Sindh.Pdf

Rani Bagh, Hyderabad “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Hyderabad August 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader de velopment programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

The Ultimate Dimension of Life’ During His(RA) Lifetime

ABOUT THE BOOK This book unveils the glory and marvellous reality of a spiritual and ascetic personality who followed a rare Sufi Order called ‘Malamatia’ (The Carrier of Blame). Being his(RA) chosen Waris and an ardent follower, the learned and blessed author of the book has narrated the sacred life style and concern of this exalted Sufi in such a profound style that a reader gets immersed in the mystic realities of spiritual life. This book reflects the true essence of the message of Islam and underscores the need for imbibing within us, a humane attitude of peace, amity, humility, compassion, characterized by selfless THE ULTIMATE and passionate love for the suffering humanity; disregarding all prejudices DIMENSION OF LIFE and bias relating to caste, creed, An English translation of the book ‘Qurb-e-Haq’ written on the colour, nationality or religion. Surely, ascetic life and spiritual contemplations of Hazrat Makhdoom the readers would get enlightened on Syed Safdar Ali Bukhari (RA), popularly known as Qalandar the purpose of creation of the Pak Baba Bukhari Kakian Wali Sarkar. His(RA) most devout mankind by The God Almighty, and follower Mr Syed Shakir Uzair who was fondly called by which had been the point of focus and Qalandar Pak(RA) as ‘Syed Baba’ has authored the book. He has been an all-time enthusiast and zealous adorer of Qalandar objective of the Holy Prophet Pak(RA), as well as an accomplished and acclaimed senior Muhammad PBUH. It touches the Producer & Director of PTV. In his illustrious career spanning most pertinent subject in the current over four decades, he produced and directed many famous PTV times marred by hatred, greed, lust, Plays, Drama Serials and Programs including the breathtaking despondency, affliction, destruction, and amazing program ‘Al-Rehman’ and the magnificient ‘Qaseeda Burda Sharif’. -

Shahmurad Sugar Mills Limited

SHAHMURAD SUGAR MILLS LIMITED Half Yearly Results for the period 1st October 2019 to 31st March, 2020 SHAHMURAD SUGAR MILLS LTD. COMPANY INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS MR. ZIA ZAKARIA Managing Director & CEO MR. ABDUL AZIZ AYOOB MR. NOOR MOHAMMAD ZAKARIA MRS. SANOBAR HAMID ZAKARIA MR. NAEEM AHMED SHAFI Independent Director MR. KHURRAM AFTAB Independent Director BOARD AUDIT COMMITTEE MR. NAEEM AHMED SHAFI Chairman MR. NOOR MOHAMMAD ZAKARIA Member MRS. SANOBAR HAMID ZAKARIA Member HUMAN RESOURCE AND REMUNERATION COMMITTEE MR. KHURRAM AFTAB Chairman MR.NOOR MOHAMMAD ZAKARIA Member MR. ZIA ZAKARIA Member CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER MR. ZAID ZAKARIA COMPANY SECRETARY MR. MOHAMMAD YASIN MUGHAL FCMA AUDITORS M/s. KRESTON HYDER BHIMJI & CO. Chartered Accountants LEGAL ADVISOR MR. IRFAN Advocate REGISTERED OFFICE 96-A, SINDHI MUSLIM HOUSING SOCIETY, KARACHI-74400 Tel: 34550161-63 Fax: 34556675 FACTORY JHOK SHARIF, TALUKA MIRPUR BATHORO, DISTRICT SUJAWAL (SINDH) REGISTRAR & SHARES REGISTRATION OFFICE M/S C & K MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATES (PVT) LTD. 404-TRADE TOWER, ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD, NEAR METROPOLE HOTEL, KARACHI - 75530 WEBSITE www.shahmuradsugar.co 1 SHAHMURAD SUGAR MILLS LTD. DIRECTORS' REPORT Dear Members Asslamu Alaikum On behalf of Board, I take the opportunity to present before you with great pleasure the un-audited financial statements of your company for the period ended March 31, 2020. The financial statements have been reviewed by the Auditors as required under the Code of Corporate Governance. Salient features of production and Financial Statements -

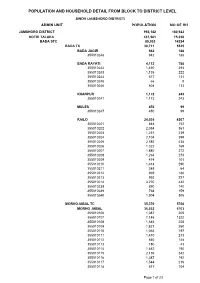

Jamshoro Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAMSHORO DISTRICT 993,142 180,922 KOTRI TALUKA 437,561 75,038 BADA STC 85,033 14234 BADA TC 30,711 5525 BADA JAGIR 942 188 355010248 942 188 BADA RAYATI 4,112 788 355010242 1,430 294 355010243 1,135 222 355010244 677 131 355010245 66 8 355010246 804 133 KHANPUR 1,173 243 355010241 1,173 243 MULES 450 99 355010247 450 99 RAILO 24,034 4207 355010201 844 152 355010202 2,054 361 355010203 1,251 239 355010204 2,104 399 355010205 2,585 438 355010206 1,022 169 355010207 1,880 272 355010208 1,264 273 355010209 474 101 355010210 1,414 290 355010211 348 64 355010212 969 186 355010213 993 227 355010214 3,270 432 355010238 890 140 355010239 768 159 355010240 1,904 305 MORHOJABAL TC 35,370 5768 MORHO JABAL 35,032 5703 355010106 1,087 205 355010107 7,146 1322 355010108 1,646 228 355010109 1,821 260 355010110 1,065 197 355010111 1,410 213 355010112 840 148 355010113 180 43 355010114 1,462 190 355010115 2,136 342 355010116 1,387 192 355010117 1,544 216 355010118 617 104 Page 1 of 23 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 355010119 79 15 355010120 3,665 538 355010121 951 129 355010122 2,161 343 355010123 2,169 355 355010124 1,468 261 355010125 2,198 402 TARBAND 338 65 355010126 338 65 PETARO TC 18,952 2941 ANDHEJI-KASI 1,541 292 355010306 1,541 292 BELO GHUGH 665 134 355010311 665 134 MANJHO JAGIR 659 123 355010307 659 123 MANJHO RAYATI 1,619 306 355010310 1,619 -

Professor Annemarie Schimmel1 (April 7, 1922 to January 26, 2003)

Professor Annemarie Schimmel1 (April 7, 1922 to January 26, 2003) Annemarie Brigitte Schimmel, who died aged 80 on 26th January 2003, was the West’s most outstanding expert on Sufism, classical and folk Islamic poetry, Indo-Pakistani literature, and calligraphy. By the time of her sudden death following an accident aggravated by medical complications, she had written and translated not only 105 works and numerous scholarly and popular articles, but also poetical compositions in the spirit of medieval mystics such as al-Hallaj (d. 922 AD); Hafiz (d. 1380 AD); and Rumi (d. 1273 AD) – on whom she was the foremost western specialist long before he became a best-seller among new-age occidentals. Her impressive output was attributable to a solid grounding in not only the Islamic “tripos” of Arabic, Persian and Turkish but also Urdu, Pashto and Sindhi. For good measure she also added Czech and Swedish to her native German, and also Latin, English, French and Italian. She read and corresponded in twenty-five languages and was able to deliver extemporaneous lectures serenely, in ten languages, with her eyes shut to enraptured audiences for an hour or even longer. After concluding with a memorable verse, she conveyed her audience from the sublime to the mundane albeit mesmerised. Born in historic Erfurt, also hometown of the German mystic Meister Eckhart, Annemarie Schimmel grew up in a house “permeated with religious freedom and poetry”. She began studying Arabic at 15, finished high school two years earlier than customary, and obtained her first doctorate from Berlin University in 1941 at 19 in Arabic, Turkish and Islamic history. -

Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization (JITC) Article: Discourse

Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization (JITC) Volume 9, Issue 2, Fall 2019 pISSN: 2075-0943, eISSN: 2520-0313 Journal DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc Issue DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.92 Homepage: https://www.umt.edu.pk/jitc/home.aspx Journal QR Code: Discourse on Nationalism: Political Ideologies of Indexing Article: Two Muslim Intellectuals, Maulana Hussain Partners Ahmad Madani and Allama Muhammad Iqbal Author(s): Shahid Rasheed Humaira Ahmad Published: Fall 2019 Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.32350/jitc.92.05 QR Code: Rasheed, Shahid, and Humaira Ahmad. “Discourse on nationalism: Political ideologies of two Muslim To cite this intellectuals, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani and article: Allama Muhammad Iqbal.” Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 9, no. 2 (2019): 89–109. Crossref This article is open access and is distributed under the Copyright terms of Creative Commons Attribution – Share Alike Information: 4.0 International License For more Department of Islamic Thought and Civilization, please Publisher School of Social Science and Humanities, click here Information: University of Management and Technology Lahore, Pakistan. Department of Islamic Thought and Civilization 89 Volume 9 Issue 2, Fall 2019 Discourse on Nationalism: Political Ideologies of Two Muslim Intellectuals, Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madani and Allama Muhammad Iqbal Shahid Rasheed∗ Department of Sociology Forman Christian College University, Lahore, Pakistan Humaira Ahmad Department of Islamic Thought and Civilization University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract The chief purpose of this paper is to understand and compare the political ideologies of two key thinkers and leaders of twentieth century Muslim India on the question of nationalism. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

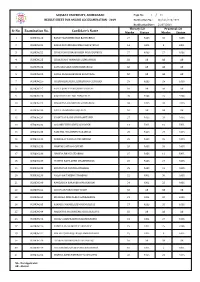

Gujarat University, Ahmedabad Result Sheet for Online Ccc Examination

GUJARAT UNIVERSITY, AHMEDABAD Page No.: 1 / 44 RESULT SHEET FOR ONLINE CCC EXAMINATION - 2019 Notification No. : GU/CCC/123/2019 Notification Date : 21/07/2019 Theory-50 Practical-50 Sr No. Examination No. Candidate's Name Marks Status Marks Status 1 GUB039220 BAROT MANISHKUMAR BACHUBHAI 27 PASS 36 PASS 2 GUB039221 BARIA DEVENDRAKUMAR PARVATBHAI 14 FAIL 5 FAIL 3 GUB039222 CHAUDHARI JIGNASHABEN MAHADEVBHAI 27 PASS 27 PASS 4 GUB039223 CHAUDHARY MINABEN LAXMANBHAI AB AB AB AB 5 GUB039224 SANGADA GEETABEN BHANABHAI AB AB AB AB 6 GUB039225 PATEL PRAKASHKUMAR SHANTILAL AB AB AB AB 7 GUB039226 CHANDRESHBHAI LAXMANSINH CHAUHAN 29 PASS 29 PASS 8 GUB039227 PATEL SHREYANKKUMAR VADILAL AB AB AB AB 9 GUB039228 SAGATHIYA HITESH PUNJABHAI 28 PASS 26 PASS 10 GUB039229 MAKWANA KIRANBHAI GOBARBHAI 33 PASS 33 PASS 11 GUB039230 PATEL USHABEN KANJIBHAI AB AB AB AB 12 GUB039231 VAGHELA PRADIPSINH ROHITSINH 27 PASS 31 PASS 13 GUB039232 SOLANKI VIPULSINH JAVANSINH 13 FAIL 10 FAIL 14 GUB039233 PANCHAL NILAMBEN NARANDAS 25 PASS 27 PASS 15 GUB039234 SONAGRA PRAHLAD VELSHIBHAI 25 PASS 32 PASS 16 GUB039235 MANVAR JAYRAM GOVIND 28 PASS 36 PASS 17 GUB039236 CHAVDA BHALU SEJABHAI 27 PASS 12 FAIL 18 GUB039237 TRIVEDI KAPILABEN DHANESHWAR 26 PASS 27 PASS 19 GUB039238 KODIYATAR PANCHA KISABHAI 25 PASS 26 PASS 20 GUB039239 VALA PARITABEN PITHABHAI 22 FAIL 30 PASS 21 GUB039240 KANGASIYA KARANBHAI MANABHAI 24 FAIL 25 PASS 22 GUB039241 CHHIPA IRFANAHMED YUSUF AB AB AB AB 23 GUB039242 BHAGORA DIMPALBEN SANKARBHAI 21 FAIL 32 PASS 24 GUB039243 PARMAR NIRMALABEN MANGALDAS 27 PASS -

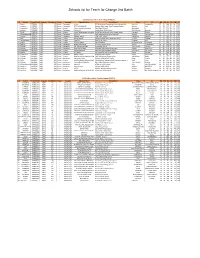

Schools List for Teach for Change 2Nd Batch

Schools list for Teach for Change 2nd Batch ESSP Schools List For Teach for Change (PHASE-II) S # District School Code Program Enrollment Phase Category Operator Name School Name Taluka UC ND NM NS ED EM ES 1 Sukkur ESSP0041 ESSP 435 Phase I Elementary Ali Bux REHMAN Model Computrized School Mubrak Pur. Pano Akil Mubarak Pur 27 40 288 69 19 729 2 Jamshoro ESSP0046 ESSP 363 Phase I Elementary RAZA MUHAMMAD Shaheed Rajib Anmol Free Education System Sehwan Arazi 26 28 132 67 47 667 3 Hyderabad ESSP0053 ESSP 450 Phase I Primary Free Journalist Foundation Zakia Model School Qasimabad 4 25 25 730 68 20 212 4 Khairpur ESSP0089 ESSP 476 Phase I Elementary Zulfiqar Ali Sachal Model Public School Thari Mirwah Kharirah 27 01 926 68 31 711 5 Ghotki ESSP0108 ESSP 491 Phase I Primary Lanjari Development foundation Sachal Sarmast model school dargahi arbani Khangarh Behtoor 27 49 553 69 20 705 6 ShaheedbenazirabaESSP0156 ESSP 201 Phase I Elementary Amir Bux Saath welfare public school (mashaik) Sakrand Gohram Mari 26 15 244 68 08 968 7 Khairpur ESSP0181 ESSP 294 Phase I Elementary Naseem Begum Faiza Public School Sobhodero Meerakh 27 15 283 68 20 911 8 Dadu ESSP0207 ESSP 338 Phase I Primary ghulam sarwar Danish Paradise New Elementary School Kn Shah Chandan 27 03 006 67 34 229 9 TandoAllahyar ESSP0306 ESSP 274 Phase I Primary Himat Ali New Vision School Chumber Jarki 25 24 009 68 49 275 10 Karachi ESSP0336 ESSP 303 Phase I Primary Kishwar Jabeen Mazin Academy Bin Qasim Twon Chowkandi 24 51 388 67 14 679 11 Sanghar ESSP0442 ESSP 589 Phase I Elementary -

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales by Aali Mirjat B.A., (Hons., History), Lahore University of Management Sciences, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Aali Mirjat 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Aali Mirjat Degree: Master of Arts Title: Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales Examining Committee: Chair: Evdoxios Doxiadis Assistant Professor Luke Clossey Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Bidisha Ray Co-Supervisor Senior Lecturer Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor Tara Mayer External Examiner Instructor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: July 16, 2018 ii Abstract This thesis examines Sindhi Sufi folktales as retold by five “modern” individuals: the nineteenth- century British explorer Richard Burton and four Sindhi intellectuals who lived and wrote in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Lilaram Lalwani, M. M. Gidvani, Shaikh Ayaz, and Nabi Bakhsh Khan Baloch). For each set of retellings, our purpose will be to determine the epistemological and emotional sympathy the re-teller exhibits for the plot, characters, sentiments, and ideas present in the folktales. This approach, it is hoped, will provide us a glimpse inside the minds of the individual re-tellers and allow us to observe some of the ways in which the exigencies of a secular western modernity had an impact, if any, on the choices they made as they retold Sindhi Sufi folktales. -

Affidavit in Support of Criminal Complaint

AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT OF CRIMINAL COMPLAINT I, Joseph W. Ferrell, being first duly sworn, state as follows: INTRODUCTION AND AGENT BACKGROUND 1. I am a Special Agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI“). I have been in this position since May 12, 2019. Prior to joining the FBI, I served four and a half years in the United States Army, most recently as a Squad Leader in the 82nd Airborne Division, to include a ten month deployment to Afghanistan. After completing my enlistment with the Army, I was a Management Analyst on an Internal Performance Audit team with the National Science Foundation, working on an audit of government accountability for equipment purchased on multi- million dollar grants. Since joining the FBI, I have been assigned to an extraterritorial terrorism squad primarily investigating terrorism financing operations. I am assigned to the Washington Field Office of the FBI. 2. This affidavit is being submitted in support of a criminal complaint alleging that MUZZAMIL ZAIDI (ZAIDI), ASIM NAQVI, ALI CHAWLA, and others known and unknown have conspired to provide services to Iran and the government of Iran (GOI), by collecting money in the United States on behalf of the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Ayatollah Ali Husseini Khamenei (hereinafter, the Supreme Leader of Iran), and causing the money to be transported to Iran, without having first obtained a license from the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), as required by law, in violation of 50 U.S.C. §§ 1701-1705. The complaint also alleges that ZAIDI has acted within the United States as an agent of the GOI without having first notified the Attorney General, in violation of 18 U.S.C § 951.