Mcclellan-Podcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Change Commission

Report of the Democratic Change Commission Prepared by the DNC Office of Party Affairs and Delegate Selection as staff to the Democratic Change Commission For more information contact: Democratic National Committee 430 South Capitol Street, S.E. Washington, DC 20003 www.democrats.org Report of the Democratic Change Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal ..................................................................................................................1 Introduction and Background ...................................................................................................3 Creation of the Democratic Change Commission DNC Authority over the Delegate Selection Process History of the Democratic Presidential Nominating Process ’72-‘08 Republican Action on their Presidential Nominating Process Commission Meeting Summaries ............................................................................................13 June 2009 Meeting October 2009 Meeting Findings and Recommendations ..............................................................................................17 Timing of the 2012 Presidential Nominating Calendar Reducing Unpledged Delegates Caucuses Appendix ....................................................................................................................................23 Democratic Change Commission Membership Roster Resolution Establishing the Democratic Change Commission Commission Rules of Procedure Public Comments Concerning Change Commission Issues Acknowledgements Report -

Introduction to Virginia Politics

6/18/2021 Introduction to Virginia Politics 1 Things to Understand about 2 Virginia Politics Virginia is a Commonwealth (as are Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky) Significant to the Virginians who declared independence in 1776 – probably looking at the “commonwealth” (no king) during the English Civil War of the 1640s – 1650s. No current significance 2 Things to Understand about 3 Virginia Politics Voters do not register by political party Elections are held in odd-numbered years House of Delegates every 2 years State-wide offices—every 4 years (in the year AFTER a Presidential election) State Senate—every 4 years (in the year BEFORE a Presidential election) 3 1 6/18/2021 More Things to Understand 4 about Virginia Politics “Dillon Rule” state Independent Cities No campaign finance limitations for state elections 4 5 Virginia State Capitol, 6 Richmond, VA Designed by Thomas Jefferson Dedicated in 1788 6 2 6/18/2021 7 8 9 9 3 6/18/2021 The General Assembly 10 The official name of the State Legislature Dates from1619 Senate and a House of Delegates Meets annually, beginning in January, 60 days in even-numbered years (long session) 30 days in odd-numbered years (short session) 10 11 Year Chamber Membership Salary Elected House of 100 2019 $17,640++ Delegates (55D-45R) 40 Senate 2019 $18,000++ (21D-19R) 11 Partisan Breakdown in Virginia – 12 House of Delegates Year Democrats Republicans Independents 1960 96 4 0 1970 75 24 1 2000 50 49 1 2010 39 59 2 2016 34 66 0 2018 49 51 0 2020 55 45 0 12 4 6/18/2021 13 2019 House of Delegates Election 55 Democrats 45 Republicans 13 14 14 15 2019 Virginia State Senate Election Results 21 Democrats, 19 Republicans 15 5 6/18/2021 Partisan Breakdown in Virginia – State Senate 16 Year Democrats Republicans 1960 38 2 1970 33 7 1980 32 9 1990 30 10 2000 19 21 2010 22 18 2018 19 21 2020 21 19 Note: --Republicans and Democrats were tied 20-20 from 1996-2000 and again from 2012-2015. -

Letter Signed by 58 Members of the Virginia General Assembly

m STATE CORPORATION COMMISSION Division of Information Resources © June 5, 2020 MEMORANDUM TO: Document Co Clerk’s Office FROM: KenSchrad m30 RE: PUR-2020-001 I have attached a letter signed by 58 members of the Virginia General Assembly. Sent from the office of Delegate Jerrauld “Jay” Jones, I received the email on Friday afternoon, June 5, 2020. I ask that you pass this correspondence to the referenced case file. PUR-2020-00048 Ex Parte: Temporary Suspension of Tariff Attachment - Letter signed by 44 members of the Virginia House of Representatives and 14 members of the Virginia Senate S ID i) 8 IS June 5, 2020 ® 1 (! VIA ELECTRONIC FILING £ Honorable Mark C. Christie Chairman State Corporation Commission 1300 E. Main Street Richmond, VA 23219 Re: Commonwealth of Virginia, ex rel. State Corporation Commission, Ex Parte: Temporary Suspension of Tariff Requirements Case No. PUR-2020-00048 Dear Commissioner Christie: We greatly appreciate the State Corporation Commission’s continued efforts to protect Virginia consumers during the economic crisis caused by the Coronavirus pandemic (“COVID- 19”). Please accept this informatory letter in response to issues and questions raised in the Commission’s May 26 Order in the referenced docket. In its Order, the Commission asserted that the current moratorium on utility service disconnections for nonpayment “is not sustainable” and could result in costs being “unfairly shifted to other customers.” The Order also suggested that this moratorium could have “negative impacts on small, less-capitalized utilities and member-owned electric cooperatives,” which “could impact vital services to all customers of such utilities.” The Commission requested comment regarding whether the current moratorium should be continued, and if so, for how long. -

Alabama at a Glance

ALABAMA ALABAMA AT A GLANCE ****************************** PRESIDENTIAL ****************************** Date Primaries: Tuesday, June 1 Polls Open/Close Must be open at least from 10am(ET) to 8pm (ET). Polls may open earlier or close later depending on local jurisdiction. Delegates/Method Republican Democratic 48: 27 at-large; 21 by CD Pledged: 54: 19 at-large; 35 by CD. Unpledged: 8: including 5 DNC members, and 2 members of Congress. Total: 62 Who Can Vote Open. Any voter can participate in either primary. Registered Voters 2,356,423 as of 11/02, no party registration ******************************* PAST RESULTS ****************************** Democratic Primary Gore 214,541 77%, LaRouche 15,465 6% Other 48,521 17% June 6, 2000 Turnout 278,527 Republican Primary Bush 171,077 84%, Keyes 23,394 12% Uncommitted 8,608 4% June 6, 2000 Turnout 203,079 Gen Election 2000 Bush 941,173 57%, Gore 692,611 41% Nader 18,323 1% Other 14,165, Turnout 1,666,272 Republican Primary Dole 160,097 76%, Buchanan 33,409 16%, Keyes 7,354 3%, June 4, 1996 Other 11,073 5%, Turnout 211,933 Gen Election 1996 Dole 769,044 50.1%, Clinton 662,165 43.2%, Perot 92,149 6.0%, Other 10,991, Turnout 1,534,349 1 ALABAMA ********************** CBS NEWS EXIT POLL RESULTS *********************** 6/2/92 Dem Prim Brown Clinton Uncm Total 7% 68 20 Male (49%) 9% 66 21 Female (51%) 6% 70 20 Lib (27%) 9% 76 13 Mod (48%) 7% 70 20 Cons (26%) 4% 56 31 18-29 (13%) 10% 70 16 30-44 (29%) 10% 61 24 45-59 (29%) 6% 69 21 60+ (30%) 4% 74 19 White (76%) 7% 63 24 Black (23%) 5% 86 8 Union (26%) -

Legislative Staff

Legislative Staff Assistants, Chiefs of Staff, Policy Directors & Counsel Adams, Tyler • Senate: Bryce Reeves • 804.698.7517 • GA Room 312 Anyadike, Chika • House: Lashrecse Aird • 804.698.1063 • GA Room 817 Arnold, Jed • House: Jeffrey Campbell • 804.698.1006 • GA Room 708 Baptista Araujo, Kat • House: Joseph Yost • 804.698.1012 • GA Room 518 Aulgur, Jennifer • Senate: Mark Obenshain • 804.698.7526 • GA Room 331 Babb, Jameson • House: Peter Farrell • 804.698.1056 • GA Room 528 Barts, Gayle F. • House: Les Adams • 804.698.1016 • GA Room 719 Johnston Batten, Amanda • House: Brenda Pogge • 804.698.1096 • GA Room 403 Bennett, Pat • House: Riley Ingram • 804.698.1062 • GA Room 404 Bingham, Carmen • House: David Toscano • 804.698.1057 • GA Room 614 Blanks-Shearin, Cindy • House: Matt Fariss • 804.698.1059 • GA Room 808 Blencoe, Justine • Senate: Jennifer McClellan • 804.698.7509 • GA Room 310 Boone, Tempestt • House: Cia Price • 804.698.1095 • GA Room 818 Bovenizer, David A. • House: Lee Ware • 804.698.1065 • GA Room 421 Bowman, Thomas • House: Paul Krizek • 804.698.1044 • GA Room 422 Boyd, Jennifer • Senate: John Edwards • 804.698.7521 • GA Room 301 Bradley, Shelia • House: James Edmunds • 804.698.1060 • GA Room 805 Bradshaw, Robbie • House: Steve Heretick • 804.698.1091 • GA Room 809 Brown, Shakira • House: Joe Lindsey • 804.698.1090 • GA Room 505 Cabot, Devon • Senate: Jeremy McPike • 804.698.7529 • GA Room 317 Campbell, Courtney • House: Sam Rasoul • 804.698.1011 • GA Room 814 Carter, Abby • Senate: Jennifer Wexton • 804.698.7533 • GA -

Strong Turnout for Jewish Advocacy

Jewish Community Federation | No One Builds Community Like Federation the OF RICHMOND in this issue RVolume 62 | Issue 3eflectorII Adar 5774 | March 2014 FEDERATION Strong turnout for Jewish Advocacy Day espite icy weather, nearly 200 participants more than 40 Delegates and Senators during Dfrom around the commonwealth visits on the Hill. gathered in Richmond to advocate for The legislators included: Sen. Creigh legislation that would benefit – as well as speak Deeds (Bath); Sen. Adam Ebbin (Arlington); out against bills that would be a detriment – Sen. Barbara Favola (Arlington); Sen. to the Jewish community on Jewish Advocacy Henry Marsh (Richmond); Sen. Donald Day - Date With the State, on Feb. 5. McEachin (Henrico); Sen. Ryan McDougle Members of the Jewish community met (Hanover); Sen. Walter Stosch (Henrico); PJ Library Program with Gov. Terry R. McAuliffe, Lt. Gov. Ralph Sen. John Watkins (Midlothian); Del. Betsy S. Northam and Attorney Gen. Mark Herring. Carr (Richmond); Del. Kirk Cox (Colonial PAGE 2 The three addressed the participants at the Heights); Del. Peter Farrell (Henrico); Del. luncheon session. In addition, several high- Eileen Filler-Corn (Fairfax); Del. Buddy AGENCIES level cabinet members participated. Fowler (Ashland); Del. Manoli Loupassi JCFR Board member Richard Samet, (Richmond); Del. Jimmie Massie (Henrico); chair of the Jewish Community Relations Del. Jennifer McClellan (Richmond); Del. Committee, welcomed the group at the Delores McQuinn (Richmond); Del. Joe (Right) Richard Samet, Jewish Community Relations morning session. At the luncheon session, he Morrissey (Henrico), Delegate John O’Bannon Committee chair and JCFR president-elect, thanks introduced McAuliffe. (Henrico); and Del. Lee Ware (Powhatan). Gov. Terry R. -

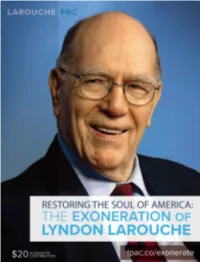

Lyndon Larouche Political Action Committee LAROUCHE PAC Larouchepac.Com Facebook.Com/Larouchepac @Larouchepac

Lyndon LaRouche Political Action Committee LAROUCHE PAC larouchepac.com facebook.com/larouchepac @larouchepac Restoring the Soul of America THE EXONERATION OF LYNDON LAROUCHE Table of Contents Helga Zepp-LaRouche: For the Exoneration of 2 the Most Beautiful Soul in American History Obituary: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. (1922–2019) 9 Selected Condolences and Tributes 16 Background: The Fraudulent 25 Prosecution of LaRouche Letter from Ramsey Clark to Janet Reno 27 Petition: Exonerate LaRouche! 30 Prominent Petition Signers 32 Prominent Signers of 1990s Statement in 36 Support of Lyndon LaRouche’s Exoneration LLPPA-2019-1-0-0-STD | COPYRIGHT © MAY 2019 LYNDON LAROUCHE PAC, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Cover photo credits: EIRNS/Stuart Lewis and Philip Ulanowsky INTRODUCTION For the Exoneration of the Most Beautiful Soul in American History by Helga Zepp-LaRouche There is no one in the history of the United States to my knowledge, for whom there is a greater discrep- ancy between the image crafted by the neo-liberal establishment and the so-called mainstream media, through decades of slanders and co- vert operations of all kinds, and the actual reality of the person himself, than Lyndon LaRouche. And that is saying a lot in the wake of the more than two-year witch hunt against President Trump. The reason why the complete exoneration of Lyn- don LaRouche is synonymous with the fate of the United States, lies both in the threat which his oppo- nents pose to the very existence of the U.S.A. as a republic, and thus for the entire world, it system, the International Development Bank, which and also in the implications of his ideas for America’s fu- he elaborated over the years into a New Bretton Woods ture survival. -

Documented in the Founding Documents Like the Federalist Papers

NO. 18-281 In the Supreme Court of the United States ________________ VIRGINIA HOUSE OF DELEGATES, M. KIRKLAND COX, Appellants, v. GOLDEN BETHUNE-HILL, et al., Appellees. ________________ On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia ________________ JOINT APPENDIX Volume II of IX ________________ MARC E. ELIAS PAUL D. CLEMENT Counsel of Record Counsel of Record PERKINS COLE, LLP KIRKLAND & ELLIS LLP 700 13th Street, NW 655 Fifteenth Street, NW Ste. 600 Washington, DC 20005 Washington, DC 20005 (202) 879-5000 [email protected] TOBY J. HEYTENS OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 202 N. 9th Street Richmond, VA 23225 Counsel for Appellees Counsel for Appellants December 28, 2018 Jurisdictional Statement Filed September 4, 2018 Jurisdiction Postponed November 13, 2018 JA i TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume I Docket Entries, United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Bethune-Hill v. Va. House of Delegates, No. 3:14-cv-00852 (E.D. Va.) ....................................................... JA-1 Opening Statement of Hon. Mark L. Cole, Chairman, Committee on Privileges and Elections, before Subcommittee on Redistricting, Virginia House of Delegates (Sept. 8, 2010) ............................................ JA-128 Email from Chris Marston to Katie Alexander Murray re RPV Leadership Roster (Dec. 9, 2010) ............................................. JA-132 Federal Register Notice, Dept. of Justice Guidance Concerning Redistricting Under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 76 Fed. Reg. 7470 (Feb. 9, 2011) . .......................... JA-135 Email from Kent Stigall to Chris Jones re District demographics, with attachments (March 9, 2011) .......................................... JA-149 Email from James Massie to Mike Wade re Help with Contested Election Information, with attachments (March 10, 2011) ................. -

No Rest for the Weary: a Survey of Virginia's 2020 General Assembly Regular and Special Sessions

Richmond Public Interest Law Review Volume 24 Issue 1 General Assembly in Review 2020 Article 3 3-31-2021 No Rest for the Weary: A Survey of Virginia's 2020 General Assembly Regular and Special Sessions Samantha R. Galina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/pilr Part of the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Samantha R. Galina, No Rest for the Weary: A Survey of Virginia's 2020 General Assembly Regular and Special Sessions, 24 RICH. PUB. INT. L. REV. 1 (2021). Available at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/pilr/vol24/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Richmond Public Interest Law Review by an authorized editor of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Galina: No Rest for the Weary: A Survey of Virginia's 2020 General Assemb Do Not Delete 3/30/2021 10:11 PM NO REST FOR THE WEARY: A SURVEY OF VIRGINIA’S 2020 GENERAL ASSEMBLY REGULAR AND SPECIAL SESSIONS Samantha R. Galina* *J.D. Candidate, Class of 2021 at the University of Richmond School of Law. Sam Galina serves as the General Assembly Editor for the University of Richmond Public Interest Law Review. Throughout law school, she has interned for the Counsel to the Governor of Virginia and was an extern with the Office of the Attorney General - Solicitor General Division. Sam is currently completing an externship with Virginia State Senator, Ghazala Hashmi. -

VA 2021 Primaries-Final

February 19, 2021 Most voters undecided in Virginia nominating contests; McAuliffe, Herring have head starts among Democrats; Chase leads Cox, Snyder for Republican governor bid Summary of Key Findings 1. Former Gov. Terry McAuliffe opens Democrats’ primary race for governor with a quarter of the vote (26%), but half of Democratic voters are undecided (49%). 2. State Sen. Amanda Chase leads Republican field for governor with 17%, with former Virginia House Speaker Kirk Cox at 10% and tech entrepreneur Pete Snyder at 6%; but 55% of Republican voters say they are undecided. 3. No candidate for lieutenant governor has made much of an impression on voters in the crowded Democratic field, with most voters undecided (78%). 4. Virginia Beach Del. Glenn Davis (8%) leads the field for the Republican lieutenant governor nomination, but most voters are undecided (71%). 5. Attorney General Mark Herring (42%) holds a commanding lead for Democrats’ nomination to a third term, but half of Democratic voters are undecided (50%). 6. Virginia Beach lawyer Chuck Smith (10%) leads the race for the Republican attorney general nomination, but two-thirds of voters are undecided (68%). 7. With all 100 House of Delegates seats up in November, Democrats lead Republicans in a generic ballot, 49% to 37%. 8. Deep partisan division defines voters, with 83% of Democrats approving Gov. Ralph Northam’s job performance, while 79% of Republicans disapprove. For further information, contact: Dr. Quentin Kidd [email protected] O: (757) 594-8499 Academic Director @QuentinKidd M: (757) 775-6932 Dr. Rebecca Bromley-Trujillo [email protected] O: (757) 594-9140 Research Director @becky_btru M: (269) 598-5008 1 Analysis Gubernatorial Races: In the Democratic primary contest for governor, former governor Terry McAuliffe leads among Democratic voters with 26%, followed by Lt. -

2019 Legislative Heroes Virginia LCV Legislative Heroes Sen

100 % 2019 Legislative Heroes Virginia LCV Legislative Heroes Sen. George Barker Sen. Jennifer Boysko Sen. Creigh Deeds Sen. Barbara Favola Sen. Janet Howell demonstrate a strong dedication and prioritization of our conservation values. This year we recognize 11 Senators and 38 Delegates for voting with Virginia LCV 100 percent of the time. Of the hundreds of bills these legislators Sen. Mamie Locke Sen. Dave Marsden Sen. Monty Mason Sen. Jennifer McClellan Sen. Jeremy McPike vote on every session, they deserve a special acknowledgment for getting the conservation vote right every time. On behalf of Conservation Voters in Virginia, we thank the Legislative Heroes pictured here and look forward to their Sen. Dick Saslaw Del. Dawn Adams Del. Lashrecse Aird Del. Hala Ayala Del. Lamont Bagby continued commitment to protecting the Commonwealth’s precious natural resources. Del. John Bell Del. Jeffrey Bourne Del. David Bulova Del. Betsy Carr Del. Jennifer Carroll Foy * Delegate Ibraheem Samirah also earned a 100 percent score in 2019. Because he was sworn in during the last week of the General Assembly, this score only reflects two recorded votes from the reconvened, April session. He is therefore not listed as a Legislative Hero for 2019. Del. Lee Carter Del. K. Convirs-Fowler Del. Karrie Delaney Del. Eileen Filler-Corn 2019 Legislative Leaders Virginia LCV Legislative Leaders scored between 75 and 99 percent on this year’s Scorecard. Ten Delegates and eight Senators earned this recognition for making Del. Wendy Gooditis Del. Elizabeth Guzman Del. Cliff Hayes Del. Charniele Herring Del. Patrick Hope conservation a priority. Virginia Senate Senator Rosalyn Dance – 93% Senator Adam Ebbin – 92% Senator Lynwood Lewis – 92% Senator Louise Lucas – 92% Del. -

Are-There-Any-Elections-In-Virginia-In-2021

1 Are-There-Any-Elections-In-Virginia-In-2021 Representative for Virginia s 8th congressional district and former Mayor of Alexandria 33 , former Minority Leader of the Virginia House of Delegates and former Mayor of Charlottesville 34 Centreville 35 Springfield , Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates 17 Alexandria , Majority Leader of the Virginia House of Delegates and former Chair of the Democratic Party of Virginia 36 Blacksburg 37 Richmond City 38 Hampton 39 McLean 35 Ashburn 35 Newport News 27 Sterling 27 Arlington 27 Dumfries 17 Jarratt 38 Richmond City 27 Annandale , former Virginia Secretary of Transportation and Public Safety 1986 1990 27 Chantilly 35 Arlington 35 Reston 40 Portsmouth , President pro tempore of the Senate of Virginia 2020 present 36 Springfield , Majority Leader of the Senate of Virginia, former Minority Leader of the Senate of Virginia, former state delegate 15 , Fairfax CountyCommonwealth s Attorney 33 Dranesville , member of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors 33 Mason , Vice Chair of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors 33 , Fairfax County Sheriff 33 At-large , Chair of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors 40 , Mayor of Richmond and former Secretary of the Commonwealth of Virginia 36 41 42 The Washington Post 43 , former Chair of the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors 40 , former Majority Leader of the Virginia House of Delegates, former Minority Leader of the Virginia House of Delegates, and former Chair of the Democratic Party of Virginia 37 , author 34 co-endorsed with Carroll Foy and McClellan 20. 81 Democratic Jennifer McClellan 58,213 11. Eliminated in primary Edit.