War of 1812 Trilogy William S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Country Notes

Clinton County Historical Association North Country Notes Issue #414 Fall, 2014 Henry Atkinson: When the Lion Crouched and the Eagle Soared by Clyde Rabideau, Sn I, like most people in this area, had not heard of ing the same year, they earned their third campaigu Henry Atkinson's role in the history of Plattsburgh. streamer at the Battle of Lundy Lane near Niagara It turns out that he was very well known for serving Falls, when they inflicted heavy casualties against the his country in the Plattsburgh area. British. Atkinson was serving as Adjutant-General under Ma- jor General Wade Hampton during the Battle of Cha- teauguay on October 25,1814. The battle was lost to the British and Wade ignored orders from General James Wilkinson to return to Cornwall. lnstead, he f retreated to Plattsburgh and resigned from the Army. a Colonel Henry Atkinson served as commander of the a thirty-seventh Regiment in Plattsburgh until March 1, :$,'; *'.t. 1815, when a downsizing of the Army took place in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The 6'h, 11'h, 25'h, Brigadier General Henry Atkinson 2'7th, zgth, and 37th regiments were consolidated into Im age courtesy of www.town-of-wheatland.com the 6th Regiment and Colonel Henry Atkinson was given command. The regiment was given the number While on a research trip, I was visiting Fort Atkin- sixbecause Colonel Atkinson was the sixth ranking son in Council Bluffs, Nebraska and picked up a Colonel in the Army at the time. pamphlet that was given to visitors. -

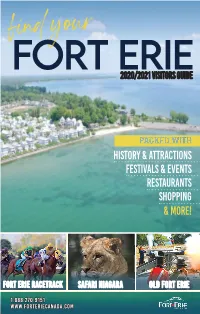

2020/2021 Visitors Guide

2020/2021 Visitors Guide packed with History & Attractions Festivals & Events Restaurants Shopping & more! fort erie Racetrack safari niagara old fort erie 1.888.270.9151 www.forteriecanada.com And Mayor’s Message They’re Off! Welcome to Fort Erie! We know that you will enjoy your stay with us, whether for a few hours or a few days. The members of Council and I are delighted that you have chosen to visit us - we believe that you will find the xperience more than rewarding. No matter your interest or passion, there is something for you in Fort Erie. 2020 Schedule We have a rich history, displayed in our historic sites and museums, that starts with our lndigenous peoples over 9,000 years ago and continues through European colonization and conflict and the migration of United Empire l yalists, escaping slaves and newcomers from around the world looking for a new life. Each of our communities is a reflection of that histo y. For those interested in rest, relaxation or leisure activities, Fort Erie has it all: incomparable beaches, recreational trails, sports facilities, a range of culinary delights, a wildlife safari, libraries, lndigenous events, fishin , boating, bird-watching, outdoor concerts, cycling, festivals throughout the year, historic battle re-enactments, farmers’ markets, nature walks, parks, and a variety of visual and performing arts events. We are particularly proud of our new parks at Bay Beach and Crystal Ridge. And there is a variety of places for you to stay while you are here. Fort Erie is the gateway to Canada from the United States. -

THE WAR of 1812: European Traces in a British-American Conflict

THE WAR OF 1812: European Traces in a British-American Conflict What do Napoleon, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the War of 1812 in North America have in common? 99 men – and this is their story… Peg Perry Lithuanian Museum-Archives of Canada December 28, 2020 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Setting the Stage ................................................................................................................................. 2 The de Watteville Regiment ................................................................................................................ 4 North America – the War of 1812 ....................................................................................................... 9 De Watteville’s Arrival in North America April to May 1813 ............................................................. 13 Loss of the Flank Companies – October 5, 1813 ............................................................................... 14 The Battle of Oswego - May 5-7, 1814 .............................................................................................. 16 The Battle of Fort Erie – August 15-16, 1814 .................................................................................... 19 Fort Erie Sortie – September 17, 1814 .............................................................................................. 23 After the War – the Land Offer in Canada........................................................................................ -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

Some Incidents and Circumstances Written by William F. Haile in the Course of His Life, 1859 Creator: Haile, William F

Title: Some Incidents and Circumstances Written by William F. Haile in the Course of his Life, 1859 Creator: Haile, William F. Dates of 1859 Record Group RG 557 Material: Number: Summary of Contents: - The first part of the document traces Mr. Haile’s lineage. His father, James Haile was a farmer. His grandfather, Amos Haile was a sailor for the early part of his life. He was placed on a British man-of- war in about 1758. He escaped and settled in Putney. (p.1) - His father’s mother’s maiden name was Parker. His mother’s maiden name was Campbell. Her father was a captain in the Revolutionary Army. (p.2) - His earliest memories revolve around the death of his aunt and the funeral of General Washington (although he did not witness this). At the time, his father was a Lieutenant in a regiment militia of Light Dragoons who wore red coats. (p.3) - In 1804, an addition was added to the Haile house which necessitated that William was to stay home to help with the building. He continued to study and read on his own. He was particularly interested in Napoleon Bonaparte’s victories. In that same year he was sent to Fairfield Academy where Reverend Caleb Alexander was the principal. (p.4) - On June 1, 1812, William was appointed as an Ensign in the Infantry of the Army of the United States. He was put into the recruiting service at Nassau (20 miles east of Albany) where he remained until September. (p.4) - He was assigned to the 11th Regiment of the W.S. -

A List of Pensioners of the War of 1812

Commodore Macdonough Painted by Gilbert Stuart. Reproduced by permission of Messrs. Rodney and Augustus R. Macdonough. A List of Pensioners of the War of 1812 Edited by BYRON N. CLARK Librarian, Vermont Antiquarian Society. H With an Appendix containing names of Volunteers for the defence of Plattsburgh from Vermont towns, a description of the battle from con- temporaneous sources, the official statement of losses, and names of United States officers and soldiers at Burlington, Vermont, as shown on army pay and muster rolls recently brought to light. RESEARCH PUBLICATION COMPANy, Burlington and Boston, 1904, THE SHELDON PRESS, PRINTERS BURLINGTON, VT, • • » / pr PREFACE /6S HE Vermont Antiquarian Society has cour- teously permitted the publication of the inter- esting record kept by William G. Shaw of Burlington, Vt., during his activity as a pen- sion agent, so far as the notes relate to soldiers in the War of 1812. This record has particular value as it includes abstracts of the evidence presented by the claimant. There was no Ver- mont law requiring vital records to be kept by town clerks prior to 1840, hence attempts to learn the families of Vermont soldiers in either the Revolution or the War of 1812 frequently are futile. All who have had occasion to seek genealogical details in Vermont will realize the importance of this pension evidence. The Volunteers whose names are printed are from the towns of Burlington, Colchester, Huntington, Milton, Under- bill, Shelburne, Jericho, and Hinesburgh, and in all, number 189. The contemporaneous accounts of the battle were copied from the newspaper files in the Fletcher Free Library at Bur- lington. -

Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812

American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. Plattsburgh, New York PREPARED FOR: The City of Plattsburgh, NY, 12901 IN ACCORDANCE WITH REQUIREMENTS OF GRANT FUNDING PROVIDED THROUGH: American Battlefield Protection Program Heritage Preservation Services National Park Service 1849 C Street NW (NC330) Washington, DC 20240 (Grant 2287-16-009) PREPARED BY: 4472 Basin Harbor Road, Vergennes, VT 05491 802.475.2022 • [email protected] • www.lcmm.org BY: Cherilyn A. Gilligan Christopher R. Sabick Patricia N. Reid 2019 1 American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Abstract As part of a regional collaboration between the City of Plattsburgh, New York, and the towns of Plattsburgh and Peru, New York, the Maritime Research Institute (MRI) at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) has been chosen to investigate six historical Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites: Valcour Island, Crab Island, Fort Brown, Fort Moreau, Fort Scott, and Plattsburgh Bay. These sites will require varying degrees of evaluation based upon the scope of the overall heritage tourism plan for the greater Plattsburgh area. The MRI’s role in this collaboration is to conduct a document review for each of the six historic sites as well as an archaeological assessment for Fort Brown and Valcour Island. The archaeological assessments will utilize KOCOA analysis outlined in the Battlefield Survey Manual of the American Battlefield Protection Program provided by the National Park Service. This deliverable fulfills Tasks 1 and 3 of the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) Grant 2887-16-009. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

The War of 1812 Magazine Issue 21 January 2014

The War of 1812 Magazine Issue 21 January 2014 Donald E. Graves. And All Their Glory Past: Fort Erie: Plattsburgh and the Final Battles in the North. Montreal: Robin Brass Studio, 2013. 419 pages, maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index. $24.95 (Canada)/$27.95 (U.S.) paper. Review by Robert Burnham And All Their Glory Past is the third book in Donald Graves “Forgotten Soldiers Trilogy”. Unlike his previous two volumes, Where Right and Glory Lead and Field of Glory: The Battle of Crysler’s Farm, 1813, which dealt with either a specific geographic area or a single battle, And All Their Glory Past, for the most part, covers the action along the border between the United States and Canada in the latter half of 1814. This was a critical time of the war, for the fledgling American Army had become a force to be reckoned with, while the war on the European continent had ended and the British were able to send a large number of battle hardened regulars from Wellington’s disbanded Peninsular Army. Although the book is divided into five parts, it really focuses on two major campaigns and a cavalry raid unlike any previously seen in North America. Much of the book centers around Fort Erie, which sits on the Canadian side of the Niagara River about a kilometer from Lake Erie. Whoever held the fort, controlled any traffic that moved on the river into the Great Lakes. Because of it strategic importance, it would become the site of the bloodiest battle on Canadian soil. Fort Erie was captured by the Americans in early July 1814 and much of And All Their Glory Past is about the attempt by the British to re-take it from August to November 1814. -

Battle of Plattsburgh, September 11, 1814

History of the War of 1812 – Battle of Plattsburgh, September 11, 1814 (Referenced to National Education Standards) Objectives: Students will be able to cite the basic facts relating to the land and water battles at Plattsburgh, New York on September 11, 1814 and be able to place the location and events into the chronological framework of the War of 1812. Time: 3 to 5 class periods, depending on extension activities. Skills: Reading, chronological thinking, map-making. Content Areas: Language Arts – Vocabulary, Language Arts- Reading, Social Studies – Geography, Social Studies - United States history. Materials: - Poster board - Colored markers/crayons - Pencils - Copies of reading materials Standards: NCHS History Standards K-4 Historical Thinking Standards 1A: Identify the temporal structure of an historical narrative or story. 1F: Create timelines. 5A: Identify problems and dilemmas confronting people in historical stories, myths, legends, and fables, and in the history of their school, community, state, nation, and the world. 5B: Analyze the interests, values, and points of view of those involved in the dilemma or problem situation . K-4 Historical Content Standards 4D: The student understands events that celebrate and exemplify fundamental values and principles of American democracy. 4E: The student understands national symbols through which American values and principles are expressed. 5-12 Historical Thinking Standards 1A: Identify the temporal structure of an historical narrative or story. 1B: Interpret data presented in time lines and create time lines. 5-12 History Content Standards Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861) 1A: The student understands the international background and consequences of the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Monroe Doctrine. -

The Battle of Plattsburg Flag 1814

The Battle of Plattsburg Flag 1814 Veteran Exempts Flag The Veteran Exempts, commanded by a Captain Melvin L. Woolsey, was a local New York militia company, formed in July of 1812, which was made up of veterans of the American Revolution who were otherwise exempt from military service because of their age. Many of the settlers in upstate New York (and Ohio) were veterans of the Revolutionary War and had been paid by grants of lands on the frontiers. By forming militia units they enabled the younger militia men to go off to war while they stayed to protect the local settlements. Like the Home Guard in Britain during the Second World War, they did provide a valuable reserve in a time of crisis. This Veteran Exempts flag may have been used at the Battle of Plattsburgh in upper New York. The Battle, also known as the Battle of Lake Champlain, ended the final British invasion attempt of the northern United States during the War of 1812. Fought shortly before the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, the American victory denied the British leverage to demand exclusive control over the Great Lakes and any territorial gains against the New England states. Little other information is available on the activities of the Veterans Exempts during the War of 1812. The Veterans Exempt flag was described in the Plattsburgh Republican, July 31, 1812, as having "...a black ground with 13 stars for the Union of White, wrought in silver. That in the centre of the Flag there he a Death's Head, with cross bones under, intimating what must soon, according to the course of nature, be their promiscuous fate, and the immediate one of any enemy who shall venture to contend with them. -

401 Spring2008 I{Orth Countryr Notes

Clinton County Historical Association lssue #401 Spring2008 I{orth Countryr Notes ,lulian O. Davidson, Marine Artist Joy A. Demarse, Ph. D On June 21, 1912, the Platts- paint the historic naval battle at be the best painting of this impor- burgh Sentinel reported that the Plattsburgh reflects not only an tant American naval bat- Honorable Smith M. Weed had acknowledgement of Davidson's tle" (Beman 45). invited "the Tercentenary Com- artistic skill but also Davidson's Was Julian Davidson's depic- mission and the rest of its distin- Plattsburgh connection: the artist tion of the naval battle at Platts- guished party" to his house on was a nephew of the Honorable burgh influenced by his visits to July 6 to view the Battle of Smith M. Weed. Davidson's his parents'family home? Did the Plattsburgh. The painting to mother, Harriet Standish David- reminiscences of his grandmother, which the Honorable Mr. Weed son, and Weeci's u'rfe, Caroline "Events of a Few Eventful Days in referred also rvas knou'n as the Standish \\ eed. were sisters. 1814" (Davidson 17-88) about the Battle o.f Lake Champlain and Julian Dar.idson's mother. Har- September 1 1 battle spark his cu- had been commrssioned by'Weed riet Standish Dar.rdson, was the riosity? Did the descriotions of in 188-l lrom American marine daughter of the Honorable Mat- Lake Champlain from his aunts' artist Julian Oliver Davidson. thew Miles Standish and Catherine writings spur his imagination? No It uould not have been un- Phebe Miiler Standish. Davidson's one knows.