Design Squad: Using Popular Media to Improve the Future of the Engineering Profession by Daniel D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PBS Kids Resources: Age Levels and Educational Philosophy

PBS Kids Resources: Age Levels and Educational Philosophy Ages 4-8 yr. olds: ARTHUR's goal is to help foster an interest in reading and writing, and to encourage positive social skills. Only available in PBS LearningMedia — Ages 3-7 yr. olds: BTL is a lively, educational blend of phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and other teaching methods for preschool, kindergarten, and first grade students. Several independent, scientifically-based read- ing research studies have shown that Between the Lions has a significant impact in in- Ages 2-5 yr. olds: "Make believe" is key to early childhood development. Ages 2-6 yr. olds: The series supports young children’s science learning by introducing sci- entific inquiry skills, teaching core science concepts and vocabulary, and preparing pre- schoolers for kindergarten and first grade science curriculum — all in whimsical style. Ages 3-7 yr. olds: Modeling of ten positive character traits that represent social and emo- tional challenges that children face and must master in the course of development. Ages 3-5 yr. olds: The goal of the series is to inspire children to explore science, engineer- ing, and math in the world around them. Ages 8-11 yr. olds: Every episode, game and activity is motivated by Cyber- chase characters and settings, and on a math concept centered on national standards. From tackling fractions in ancient Greece to using decimals to repair train tracks in Rail- road Repair, kids learn that math is everywhere and a useful tool for solving problems. Ages 2-4 yr. olds: This series, for a new generation of children, tells its engaging stories about the life of a preschooler using musical strategies grounded in Fred Rogers’ land- mark social-emotional curriculum. -

Minor League

WXXI-TV/HD | PBS WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTERLISTINGSM AY 2 010 Minor League This month, WXXI presents Minor League, a reality based 13-episode series featuring the Rochester Red Wings and the little-known world of minor league baseball in America. Produced by Campbell Media in association with WXXI, the series followed the the Triple-A affiliate of the Minnesota Twins through the entire 2009 season, starting with Spring Training in Ft. Myers, Florida. It captured the Team on the road, throughout 13 International League cities. The crew also followed members of the Team to Portland, Oregon for the Over 5,000 items inclu 2009 Triple-A All Star Game. At home, viewers will see how the players live, outside of the ballpark, during their rare time off. CBS News and 48 Hours Correspondent Erin Moriarty narrates the series. Multi-platinum recording artist, Eddie Money, contributed the theme song for Minor League. Additional music includes performances by Rochester-area bands. Minor League airs Sundays at 6:30 p.m. on Photo credit: 20 Toe Photo WXXI-TV/HD, beginning May 9 Executive Staff MAY 2010 Volume 1, Issue 9 Norm Silverstein, President & CEO Member & Audience Services ... 585.258.0200 WXXI Main Number ................... 585.325.7500 Susan Rogers, Executive Vice President & General WXXI is a public non-commercial broadcasting station owned and op- Manager Service Interruptions ................. 585.258.0331 Audience Response Line ........... 585.258.0360 erated by WXXI Public Broadcasting Council, a not-for-profit corporation Jeanne E. Fisher, Vice President, Radio chartered by the Board of Regents of New York State. -

Download PDF of Press Kit Here

PRESS CONTACT Ellen Brodsky [email protected] 34 Sherman St. www.25texans.org Cambridge, MA 02138 https://www.facebook.com/25Texans/ (617) 407-9170 www.ellenbrodskyfilms.com STILLS For higher resolution images please go to the website: www.25Texans.org © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 © Ellen Brodsky Films 2019 ONE SENTENCE SYNOPSIS Join the quest of 25 history students, mostly Mexican American, who drive 2,000 miles from the Alamo in Texas to a Springfield, Illinois museum asking to repatriate General Santa Anna’s prosthetic leg and honoring Lincoln with a Day of the Dead altar. OVERVIEW Join the quest of 25 history students, mostly Mexican American, who drive 2,000 miles from the Alamo in Texas to a Springfield, Illinois museum asking to repatriate General Santa Anna’s prosthetic leg and honoring Lincoln with a Day of the Dead altar. With humor, humility, and animated history lessons, these students raise questions of identity, borders, museum ethics, and collective memory. LONGER SYNOPSIS “A beautiful, stirring, and redemptive story about learning and especially about teaching. A history lesson, and more.” -Jill Lepore, Harvard University, author of “These Truths: A History of the United States” Join the quest of 25 history students, mostly Mexican American, who drive 2,000 miles from the Alamo in Texas to a Springfield, Illinois museum asking to repatriate General Santa Anna’s prosthetic leg and honoring Abe Lincoln’s support of Mexico with a Day of the Dead altar. -

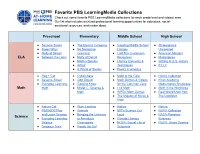

Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections Check out Some Favorite PBS Learningmedia Collections for Each Grade Level and Subject Area

Favorite PBS LearningMedia Collections Check out some favorite PBS LearningMedia collections for each grade level and subject area. Our list also includes archived professional learning opportunities for educators, social- emotional resources, and maker ideas. Preschool Elementary Middle School High School ● Sesame Street ● The Electric Company ● Inspiring Middle School ● Shakespeare ● Super Why! ● No Nonsense Literacy Uncovered ● Molly of Denali Grammar ● LGBTQ+ Curriculum ● American Masters ELA ● Between the Lions ● Molly of Denali Resources ● Masterpiece ● Martha Speaks ● Literary Elements & ● Writing in U.S. History ● Arthur Techniques ● It’s Lit ● A World of Stories ● Poetry in America ● Peg + Cat ● Cyberchase ● Math at the Core ● NOVA Collection ● Sesame Street ● Odd Squad ● Math Games & Videos ● Khan Academy ● Everyday Learning: ● Good to Know for the Common Core Mathematics Showcase Math Math ● Mister C: Science & ● I <3 Math ● Math in the Workforce Math ● WPSU Math Games ● Real World Math from ● The Majesty of Music & The Lowdown Math ● Nature Cat ● Plum Landing ● Nature ● Nature ● PBS KIDS Play ● Animals ● MIT's Science Out ● NOVA Collection and Learn Science ● Bringing the Universe Loud ● NASA Planetary Science ● Everyday Learning: to America’s ● Climate Literacy Sciences Science Classrooms ● NOVA: Secret Life of ● NOVA: Gross Science ● Dinosaur Train ● Ready Jet Go! Scientists ● Let’s Go Luna ● All About the Holidays ● Teaching with Primary ● Access World Religions ● Xavier Riddle and ● NY State & Local Source Inquiry Kits -

Design Squad Nation Build Big Contest WINNERS Release FINAL

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Design Squad Nation Announces Winners of Build Big Contest Grand-Prize Winner Invents String Instrument that Plays Bach’s J’esu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Contest Challenged Kids to Think Big By Creating their Own Super-Sized Design Squad Activity BOSTON, MA (September 08, 2011) – Design Squad Nation, the series that works side by side with kids to help turn their dreams into reality, is pleased to announce the winners of its 2011 Build Big Contest. Paul Poulos, Kalin Ngo, and Robert Schill, students from Westlake High School in Westlake, Ohio, used rubber bands, plywood, and a lot of ingenuity to create a musical instrument that plays Bach’s J’esu, Joy of Man’s Desiring. Paul, Kalin, and Robert learned about the Build Big Contest through a Design Squad class offered at Westlake High by their teacher Scott Kutz. One of the only classes of its kind, it uses Design Squad activities and videos to give kids hands-on experiences with engineering. “The US is lagging behind other countries in science, math and engineering,” says Scott Kutz. “With Design Squad, I’m able to expose kids to an interest and passion they might not have had.” “With this class and Design Squad, I get to learn how to be creative and make things through real life problem solving,” says Robert. Kalin agrees. “I would never have known I could do this without Design Squad. I’m not usually someone who would even think about using tools, but this project changed that.” The Build Big Contest challenged teams of kids, led by a mentor adult, to super-size one of Design Squad’s 40 hands-on activities found online at PBSKIDSGO.org/designsquad. -

WVIA V-Media Newsletter "People Change and Lives Improve When Powerful Ideas Challenge Us

file:///C|/Documents and Settings/Calesta Schmitt.WVIAFMTV/Local Settings/Temp/fcctemp/Attach0 13.html You're receiving this email because of your school is a member of WVIA V-Media services. Please confirm your continued interest in receiving email from us. You may unsubscribe if you no longer wish to receive our emails. WVIA V-Media Newsletter "People change and lives improve when powerful ideas challenge us. WVIA public media is a regional catalyst, convener and educator, using media, parternships, ideas and programs to advance the best attributes of an enlightened society." in this issue :: The Financial Meltdown :: Real Kids Doing Real Science :: Students bridging the gap of Alzheimers Disease :: The Bible's Buried Secrets :: Mapping Stem Cell Research :: Design Sqaud :: Watch Scholastic Scrimmage and Artist of the Week :: Coming Soon: Looking for Lincoln DVDs and Teacher Guides available from The Pennsylvania College of Technology WVIA and Penn Tech have teamed up to provide educators with new resources to help illustrate the exciting careers available in the field of technology. We are very proud to present the first of a series on Nanotechnology. Please visit WVIA's website at www.wvia.org/education to download the curriculum guides or call Andrea O'Neill at (570) 602-1182 file:///C|/Documents and Settings/Calesta Schmitt.WVIAFMTV/Local Settings/Temp/fcctemp/Attach0 13.html (1 of 4)11/24/2008 10:59:43 AM file:///C|/Documents and Settings/Calesta Schmitt.WVIAFMTV/Local Settings/Temp/fcctemp/Attach0 13.html I.O.U.S.A. Mapping Stem Cell Research: Terra Incognita Wake up, America.. -

PBS Learn More Report

PBS: LEARN MORE The Impact of America’s Largest Classroom on Learning PBS: LEARN MORE THE IMPACT OF AMERICA’S LARGEST CLASSROOM ON LEARNING Table of Contents Foreword . 4 Overview . 5 Part 1: PBS and Learning: 2015 Literature Review and Quantitative Analysis . 6 Part 2: 2015 PBS LearningMedia Impact Study . 14 Part 3: 2015 Future of Digital Learning Survey . 18 Conclusion . 21 Endnotes . 22 PBS Education | 3 Foreword At PBS, education is in our DNA. PBS was founded to use the power of media to educate, digital offerings at home and in school designed to help engage, and inspire all Americans . We take that mission people learn anywhere at anytime . very seriously . Just as we have done for decades, we test and evaluate For decades, we’ve used our on-air content to get the educational effectiveness of our content to guide children ready for success in school and in life . We have us in how to create and deliver media that impacts also sparked people’s curiosity about the world around achievement for learners of all ages . This report them, paving the way for a nation of lifelong learners . highlights the results of three studies that prove that our PBS content does more than entertain, it also inspires work is truly making a difference in learning . and teaches viewers of all ages . This report would not have been possible without our member stations and partners, including the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, who have worked with us to We have also sparked people’s curiosity “ both produce and evaluate much of the content studied . -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For More Information Contact: JULY 13, 2009 Brooks Addicott [email protected]/435-776-7857 Amy McGee [email protected]/310-492-2333 SUNDANCE INSTITUTE EXPANDS SUPPORT FOR INDIE FILM PRODUCERS WITH CREATIVE PRODUCING INITIATIVE New Documentary Creative Producing Lab Added; Feature and Documentary Film Fellows Announced LOS ANGELES, CA – Sundance Institute announced today the expansion of its Creative Producing Initiative designed to nurture emerging independent producers in both narrative and documentary fields. For 2009-2010, the Initiative will include the re-conceived Creative Producing Summit (formerly the Independent Producers Conference), the Creative Producing Lab supporting six Fellows from the Feature Film Program and, new for this year, four from the Documentary Film Program, as well as Sundance Industry Meetings to connect filmmakers with industry members at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival. The Creative Producing Initiative is designed to support producers with project-specific support through Labs, grants, and long-term advisor relationships and to also reinvigorate dialogue within the independent producing community. Fellows from four of Sundance Institute's programs: Feature Film Program, Documentary Program, Sundance Film Festival, and Native American Program have been selected to participate in Creative Producing Initiative activities, bring a wide range of projects, experiences and backgrounds. "The vitality of independent producers is crucial to the quality and abundance of independent cinema, and we are committed to deepening the Institute's support with the expanded Creative Producing Initiative," said Anne Lai, Producer in Residence, Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. "We believe this expansion will not only support the next generation of independent producers, but renew the community of veteran producers committed to the vibrancy of independent film." The Creative Producing Summit, to be held July 24-26 at the Sundance Resort, is an invitation-only event for up to 40 producers and directors. -

Magazine May 2009

Magazine MAy 2009 Michelangelo Revealed Airing Wednesday, May 13, 7:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. Airing in three parts, Wednesdays, May 6, 13, and 20, 8:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. Arkansas Educational Television Network Contents AETN MAGAZINE Staff On The Cover.... Editor in Chief On the Cover........2 Allen Weatherly The perfect gift for Mother’s Day? Concert SECRETS OF THE DEAD: Editors MICHELANGELO REVEALED Mona Dixon Concert tickets from the AETN Information.........3 Kathy Atkinson From the Throughout his masterful career, Michelangelo glorified Foundation Box Office Editorial & Creative Directors Director...............4 the church, etching Catholic ideals into the sculptures Sara Willis Answers From and artwork that defined religion for the masses. Elizabeth duBignon Viewer Services....5 Now, 500 years after his death, art historian Antonio Violinist Mairead and vocalists Chloe and Lisa will be Forcellino has found evidence of Michelangelo’s Editorial Panel Celtic Woman ‘Isle of Education.............6 Rowena Parr, Pam Wilson, Dan Koops joined by new vocalists Lynn and Alex for a night involvement with a clandestine fellowship trying Tiffany Verkler Hope’ Concert Outreach.............7 to reform the Catholic Church from within. The of unforgettable performances. group’s radical ideas and accusations of corruption Copy Editors In Their Words.....8 Darbi Blencowe, Catherine Mays, Memorial Gift were considered heretical and punishable by death. Shirley Bowen, Pat Pearce The AETN Foundation welcomes Celtic Woman’s Information.........8 Michelangelo’s involvement put him at dangerous Isle of Hope Tour to Alltel Arena in Little Rock, Tickets are available by calling toll-free 1(800) odds with powerful officials who held his livelihood AETN Offices 662-2386 or by visiting the AETN Foundation Box Local Productions — and life — in their hands. -

Social-Emotional Learning

DIGITAL BACKPACK SOCIAL EMOTIONAL LEARNING Dear Parents and Caregivers, For the last few months, your kids have been at home from school, giving you the added responsibility of creating educational experiences at home. We applaud you for finding creative ways to make sure learning is always fun and exciting. Running out of ideas? We're here to help! We've expanded our At-Home Learning service to keep your children learning all summer long with a new digital backpack designed to help students have fun while learning at home. The resources inside this digital backpack include: • Social-emotional learning guide for families • Family reading list • Printable hands-on activities • Tips for balancing screen time • PBS KIDS programming learning goals and reflection guide • PBS KIDS apps and associated learning goals Want more resources? Sign up for our e-newsletter at wfsu.org/education. To get free bilingual resources sent directly to your phone, text WFSU to 27448.* Feel free to reach out to us with questions. We would love to see photos of families learning with the digital backpack! E-mail us at [email protected]. The WFSU Education Team * Standard message and data rates apply. You may opt-out of these messages at any time by texting STOP to 27448. Family Guide for Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Family Reading List Only One You Rosie Revere, Engineer You are Special, Daniel Tiger! Say Something! Family Activity DANIEL TIGER'S NEIGHBORHOOD Bake “Get Out the Mad” Cookies How do you talk with your children about managing their feelings? This activity encourages children to find another way to deal with feelings like anger and frustration. -

Daily Specials 825 E

FRIDAY ** AFTERNOON ** FEBRUARY 13 THURSDAY ** AFTERNOON ** FEBRUARY 19 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Assignment: The Reading Rainbow Arthur Pepe WordGirl Tobey’s The Electric Cyberchase ‘‘Hugs Wishbone Faust’s Nightly Business KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Mister Rogers’ The Berenstain Between the Lions Design Squad Reading Rainbow Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl (S) (EI) Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase (S) Wishbone ‘‘A Tale Nightly Business Street (S) Neighborhood (S) Bears (S) (S) (EI) World ‘‘June 29, 1999.’’ shares his story. robot is an artist. Company (N) (S) and Witches’’ deal with the devil. Report (N) (S) Street (S) (EI) Neighborhood (S) Bears (S) Roodles the Clown. ‘‘Aquatic Robotics’’ ‘‘Beegu’’ (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) (EI) of Two Sitters’’ (S) Report (N) (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives Philip tells Stephanie The Tyra Banks Show (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘Growin’ Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show John News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News KTIV f X News (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) The Tyra Banks Show The trend of girl Little House on the Prairie Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show Jeff Probst. News NBC Nightly News and Brady that Melanie has been fired. -

THE HISTORY CHANNEL - TRIO: AMUNDSEN, Printing to Learn About Paper Money

Edward TelJcr. who helped develop the bomb; Paul Ni1Ze. who production of currency. Part 1. "What's it Worth." discusses what participated in the Strategic Bombing Survey, George Elsey. a sets the value of currency, how did money develop and how naval aide to Truman; Donald Russell. an aide to Secretary of money has changed over the centuries. Part 2. "It's as Gold," is State Arthur Byrnes; and other participants in the U.S.• Britain. all about gold and the value ofgold. Part 3. "Minting Money." Japan and Russia. takes you to the United States Mint in Philadelphia where you can watch the making ofaquarter. Part 4. "Printing Money," takes you to Washington DC to the Bureau ofEngraving and THE HISTORY CHANNEL - TRIO: AMUNDSEN, Printing to learn about paper money. Part 5, ''Money in Other SCOTT AND BYRD Countries," is about how currencies are made and used in other M-J,.H countries. ThursdJzy. August. 03, 9:00-10:00 am Exclusive expeditionary scenes and actual recordings TLC - TLC ELEMENTARY SCHOOL: MONEY: chronicle the dramatic stories ofthese Arctic explorers. KIDS AND CASH: MONEY AND YOU K-3.~,SM l1li Tuesday, September. 12, 4:00-5:00 am Tuesday, October, 17, 4:00-5:00 am TLC - OFF-AIR TAPING Tuesday, November, 21. 4:00-5:00 am Tuesday, December. 26. 4:00-5:00 am Educators will be able to videotape "TLC Elementary School." the new commercial-free series and use up to two years This five part series profiles finance. youth and the entrepre from the last date the programs airs.